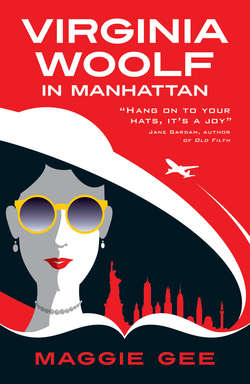

Читать книгу Virginia Woolf in Manhattan - Maggie Gee - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

VIRGINIA

Suddenly there’s time again; & I’m in it.

Plenty of time.

(Is there? – or just a bright gap in the night of unknowing?)

I spent … seven, eight decades … in the dark – a normal lifetime.

And now I am here – am I? Back on the blade of the here & now.

Will I leave any mark when I write? Will this new world read me?

Its unending light, which they all take for granted, cuts orange slats in the blinds of my room at night. Past two, three, four in the morning, the light streams on, and my head strains away like a land-locked sea lion.

I used to live, long ago, in a low quiet house, which had darkness at night & smelled of the garden, lilacs & roses, cut grass, cheroots … Leonard. June nights: him safe in the house nearby. Bats & owls, my brain racing, sometimes, but often calm – knowing I was home. One doesn’t notice how sweet … (Who was it that said ‘Observe perpetually’?)

Somehow I slipped a century. Stones in my pockets weighted me down – I sank, bursting – Then nothing. So many years in the dark. It seems I was not forgotten.

Someone longed for me, here in New York where I never went – someone hungered, and hauled me back up, protesting, dragged me through hedges & gates of dreams, and untidy, sleepy, stunned, I was suddenly half-awake in Manhattan, Virginia Woolf in Manhattan, and it is – can it be, really? – the twenty-first century. You see, I wanted –

ANGELA

I wanted to sound up to date, that was all. Because my Istanbul paper was called ‘Virginia Woolf: A Long Shadow’, and I decided to look at the primary sources. I’d forgotten a lot since I first read her. So I booked a last minute package to New York, where Woolf’s manuscripts are kept.

She did mean so much to me back when I started. Yes, she was a talisman.

Something more fundamental than the paper. Where was my life, and my writing, going? I thought it might help to be close to her.

Perhaps I should begin with my daughter. (V. never had children, of course. There I’ve done better.) Gerda is thirteen. I have kept her alive! And she’s newly away at school. A rather good one, Bendham Abbey, though no-one in my family had ever been to public school before. Hard, very hard for me, sending her away, and Edward protested … don’t think about that. Second term, Gerda would be fine. Mobiles were banned – it’s archaic, but apparently, problems with theft, concentration in lessons. I told her we could email every day …

-ish. So that was fine. In theory.

Of course, I am busy, as I explained to Gerda.

Odd thing – Virginia’s the quintessential English writer – but there they all are, in the NewYork Public Library, all those famous manuscripts, Orlando, The Waves, To the Lighthouse. In the Berg Collection, the dim red leather comfort of the Berg.

I suppose in the UK I’ve got used to being treated with a certain – not deference, no, but people have been nice to me, since I won the Iceland Prize. And the Apple Martini Prize. My name has become quite well-known. The Apple Martini shifts a lot of books, and actually made me money. Me and Gerda and Edward, that is. Holidays in Egypt, Australia, Jamaica. A new, better house. I’m a success. Success, success, that shiny slippery word, which I hope will never slip away from me.

Once people I met on planes or trains would ask ‘Will I have heard of you?’ and I would say, ‘Probably not.’ But now they say, with a dawning smile, ‘Oh yes, you’re quite famous, aren’t you?’, and ask if I’m going to write about them, and I smile at them politely, thinking ‘Not a chance.’ Then they ask me if I know JK Rowling, and I say ‘I met her at a party once, but really she was talking to Philip Pullman,’ and honestly, they still get quite excited.

I am successful, and I’m still quite young. Though not as young as I used to be.

VIRGINIA

She ran after me as if I were a brigand. Once I saw it was a middle-aged woman, I let myself be caught. But it unsettled me, the way she said my name. Not ‘Mrs Woolf’, ‘Virginia’.

She knew my name.

ANGELA

To be honest, in New York my name means very little. Whereas Virginia Woolf was huge here in her lifetime – New York Herald Tribune No 1 best-seller with The Years, on the cover of Time magazine, etc. And afterwards, she did cast a long shadow.

Growing bigger and deeper in the seventies and eighties as all the other women were eclipsed. On every university women’s studies literature course, first and dead centre: Virginia Woolf and this, Virginia Woolf and that, Virginia Woolf and the also-rans. She’s special, clearly, but all the same – isn’t it just easier to fetishise one person? Then you don’t have to think about the rest.

I’m certainly not jealous.

In her best work, she wrote for everyone. The clarity, the astonishing reach, the perception.

VIRGINIA

When I died I thought I was almost forgotten, gone.

ANGELA

So this is what happened, as I understand it. (Only Gerda will believe me. She stares right through me with those pale blue eyes half-hidden by long thin red-blonde lashes, and then she shivers and hugs herself and says, sing-song, ‘Re-ally, Mummy?’ Gerda was raised on fairytales.)

New York. No pickup at the airport. When I called the hotel to remonstrate, they said there was no record that the plane had landed. Sleepless night, glaring orange hotel sign outside my window. Everything felt frazzled and burnt out. Yet underneath, something itching, energetic.

I slept. And woke: to a new beginning.

A new day, after all, in New York! One of my favourite things, a New York morning. So what if the breakfast room was overcrowded? A fat man shouldered his way out and I nipped into his seat by the window. Sun on my eggs. Outside, the wide street streaming with purpose. I’m a positive person, it’s one of my virtues – Edward was a bit of a moaner. The gorgeous light scored straight to the park. The hotel was a dump, but near Central Park.

I love it all. The skating rink, the joggers, the lake, the spring trees, that delicate yellow – the zoo. Oh yes, I love the zoo. It’s a play zoo, really, tiny and lovely. Monkeys, bears, in the heart of the city, so alien and mysterious. Alive in the moment, so different from us.

But first of all: work to do. Off to the New York Public Library.

(Inside, part of me was still shaking. I’d felt shallow or hollow, ever since that terrible blaze of white light.)

The woman in charge of the private Berg Collection where the Woolf manuscripts are kept gave me an oblong yellow reader’s card: ‘ANGELA LAMB is hereby admitted to the BERG COLLECTION (Room 320) for research on VIRGINIA WOOLF. This card is good through 27 NOV 2025 unless revoked.’ I like membership cards. They make me feel entitled. I haven’t always felt that way.

Virginia, of course, was born entitled. But part of me is still the daughter of Lorna and Henry, born in Wolverhampton.

Statutory humblings. Abandon your coat, your briefcase, your camera, your pens, your phone before you can enter. I didn’t mind. I was excited. I couldn’t wait to get my hands on her!

Then the librarian explained.

There’s a rule that only applies to Woolf, because she is so valuable: no original manuscript material can be accessed. ‘I’m afraid you have to read her on microfilm.’ But it’s hardly the same, is it? She hasn’t breathed on that film, or used it, or touched it.

I was muttering furiously under my breath, head down because I didn’t want to be evicted from this submarine, cosy, womb-of-a-room where only the two librarians and I were working. At least I was near those manuscripts. At least I sat two feet away from the heavy glass case where the walking stick she carried on that final day was lurking, a horrible thing of dark, hooked cane. It looked – cursed. I’m allergic to suicide. And yet, it was a link to her.

Who has more right than me to read her?

All the senseless ‘No’s of my life jostled and surged in my head as I sat there. Virginia, I thought, Virginia, I crossed an ocean to get close to you. Can’t they let me reach you somehow? I sat there and longed: for her elegant angular writing, her amused, classic face. English! She was English, but these rich Americans had filched her!

Then the pleasant girl brought me one article, a strange piece Woolf had written for Hearst Magazine and Cosmopolitan in 1938, a carbon copy on thin onion-skin paper, with a few corrections in ink. The title was ‘America which I have never seen interests me most in the cosmopolitan world of today’.

And at once I was enjoying the dance. ‘Cars drive sixty or seventy abreast,’ she assures us (though she never went there!). ‘While we have shadows that walk behind us, they have a light that dances in front of them, which is the future.’ I was smiling as I read. I’ll take you home to Europe, I silently promised, if I can get to you I’ll slip you in my bag and take you back to Sussex, to Leonard, to Lewes …

Perhaps I had spoken aloud – ‘I’ll take you back to Leonard, to Lewes’ – for one of the librarians was staring at me fixedly.

Or not at me. No, behind me.

I heard, or half-heard, a croaking sound. Half-human. Distressed. Straining. And I turned in my chair. And saw.

VIRGINIA

Did I hear ‘Leonard’? Did I say ‘Leonard’? Can I now even

remember how it was?

Suddenly from nothing

was I something again?

My own voice waking me from too far away –

hearing my own voice rather deep and tremulous, I thought

& almost – old –

(for inside I was still young, a girl, when I died)

I followed it up

from the depths of cold watery sleep

into the warmth of a small dim room I did not know

a woman breathing as she read, lips half-moving, very serious,

a sigh a small smile

She was reading me with such strong desire and I wondered

‘Who is she?’

she has blonde hair but she is not young

I am on the threshold I’m too tired I don’t know

a fish jerking it’s me that she’s reading yes, it’s my soul

it’s me –

And she reeled me in, hauled me up. A strain like a tooth being pulled.

ANGELA

This woman. This strange woman. That was all I thought. Tall and dusty in bedraggled green and grey clothes. A suit. The librarian said, ‘Excuse me. May I help you?’Then closed in on her like a gaoler.

VIRGINIA

Stirring and gathering myself too late to go back –

an ache coming together

puckering a long fall of satin curtain

a wavering

a pulling together not wanting

to be seen

exposed

her eyes, their eyes

but oh –

the waking of the light

in the dark so long lost in my own crushed rib-cage

weighted with mud and slime though dying was no

worse than the terror nothing

is worse than the terror

Here, I am suddenly here.

Warm wood. Women. Electric lights. A strange room.

Two books in my hands. Yes, they’re mine. Hold them close to my body, hide them. Mine.

And, as if new-born, no fear. Was it over?

ANGELA

Almost before I knew what was happening, she was gone. In a pincer movement, two librarians hustled her out of the door. ‘If you don’t have a need for access to original material …’ one was saying, and the strange woman gaped like a fish, while the other librarian intoned, ‘The librarians in the open reading rooms will be happy to help you.’

The door swung shut. There followed a hubbub of librarian excitement, which is quiet, but the first words I could make out were ‘Who was THAT?’

And as soon as I heard it as a question, I knew the answer, and made for the door.

Out on the landing, a gaggle of Japanese tourists with cameras, a big-nosed man in a red woollen hat – but not her. So I ran down the stairs, and there, on the last flight but one, by a seat where a black boy in shades was sleeping, there she stood, yes it was her. A tall angular shape from the back, not going forward, hovering, leaning, like a tall-masted sailing ship. Her white fingers trailing on the balustrade, then touching two books, which she clutched to her ribs, shyly, as if in wonderment.

My breath caught. I slowed down, and came to her step by step.

Step

by

step.

I was afraid. I kept walking, I drew abreast.

I was any fan, any groupie, suddenly. I could see her face. Her great globes of eyes, darting down, away: hunted.

Perhaps I should have left her. But how could I have let her stumble out on to the streets of Manhattan on her own?

I had to say: ‘Virginia?’

VIRGINIA

She said my name, that first time, as if I belonged to her. They shan’t have me! She said ‘Virginia?’ and I was off like a hare. There were red ropes, I went the wrong way, a man in uniform stopped me & asked to look at ‘those books’, I had two of my own & he looked at me hard and said ‘Ma’am, are these from the library?’ – but I said ‘No’ & rushed on, with her after me. And then –

ANGELA

Half of me was laughing, half of me was shivering, nothing like this had ever happened, not to me. But I couldn’t let her go.

It was brilliant; it was impossible; it was so thrilling I could hardly breathe. It was Virginia Woolf in Manhattan. And I reached out my hand.

VIRGINIA

She touched me. It felt – electric. You see, I wanted –

ANGELA

It was like dipping my hand in water.

VIRGINIA

I wanted to come back.