Читать книгу Unfortunately, It Was Paradise - Mahmoud Darwish - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеForeword

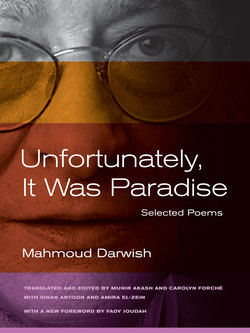

Without doubt Unfortunately, It Was Paradise is the first book to effectively introduce Mahmoud Darwish’s poetry into English. Considering that Darwish’s literary magnificence had been recognized the world over for decades prior to Paradise’s publication, this is quite an accomplishment within the English language, a breakthrough that should not be overlooked or understated. Circumstance played no small part in the easing of the decades-long negligence of Darwish’s (and Palestinian) art in the English-speaking world in general, and America in particular. The doors opened wider after the Second Intifada erupted in 2000, and were thrust ajar after September 2001. The Lannan award that same year was affirmative. Darwish received it for cultural freedom, alongside Edward Said’s award for lifetime achievement. Paradise was there, at the cusp, “like a sunflower,” “between entry and exit.” I remember hearing about the Lannan award, the announcement of the book that would follow, and Carolyn Forché’s involvement with it while I was in Zambia on medical work at that time. I had taken with me two Darwish books in Arabic to further examine the possibilities of translating his work. Nothing could have energized or spurred me on more than that news did. Political disasters notwithstanding, it seemed a prominent award and an important American poet had to offer their credibility to a major world poet for English readers to take notice. It’s ironic that Darwish would thus find himself in the company of Neruda, whose poetry did not receive much meaningful attention in English before the last decade of his life.

Since Paradise was published, a lush field of fantastic translations of Darwish’s books has given new meaning to Darwish’s beautiful phrase “my absence is entirely trees.” Most of these translations are of late works that cover the last ten or fifteen years of his forty years of writing. Most of the books are translations of single volumes. Two gather several full-length collections that display varying aspects of Darwish’s aesthetic over a short period. Two are bilingual. Each is the work of a single translator. Paradise remains the only book of selected poems of Darwish’s work in English to span his whole life. Its most immediate predecessor, The Adam of Two Edens (2000), which was created in similar manner to that of Paradise, utilizing multiple translators and a unifying editorial poetic signature, is less comprehensive. Paradise begins with twenty-five poems, exactly the first half of Fewer Roses, the book Darwish rightly considered his defining shift from the local to the global in 1986. The universal for Darwish became the private state of being, of exile not as nostalgia or status quo but as some kind of roadmap for the future of the human condition. Poetry turned into a particular type of land: one in preparation to become a place of wandering, an embodiment of nonplace.

As Paradise journeys through Darwish’s poetry, it returns us in its closing section to his beginnings. “A Soldier Dreams of White Tulips” announces Darwish’s early mastery of dialogue, and its significance reaches past the aesthetic and into political and intellectual vision. That poem was reenacted in Identity of the Soul, a 2008 multimedia art project that featured the poetry of Ibsen and of Darwish himself, and the performance of Vanessa Redgrave. Originally, the poem was written overnight in 1967, after a conversation Darwish had with his Israeli friend, the now well-known scholar Shlomo Sand. Of course, Darwish’s vision of dialogue would go on to develop into an astonishing assortment over the decades, whether in dramatist (“The Hoopoe”) or narrative (“The Everlasting Indian Fig”) mode. Similarly, the 1977 elegy to his fellow Palestinian poet Rashed Hussein, “As Fate Would Have It,” would affirm a lifetime negotiation with elegy, its private and public forms, and its interchangeability with praise. The prose quartet, “Four Personal Addresses,” is the first of its kind in Darwish’s oeuvre. Its third section examines his first encounter with ailment and death, and emerged out of combined grave heartache and heart disease at barely forty years of age: “In which heart was I struck?” he asks. The poem’s opening line, “When the earth presses against me, the wind spins me around,” pays tribute to al-Khansa, the most famous of ancient Arab women poets, as well as to al-Mutanabbi in its predicate phrase. In fact, Darwish returns to al-Khansa in Fewer Roses, in “Earth Presses against Us,” a poem from which Edward Said draws the title of his 1986 book on Palestinian representation, After the Last Sky: “Where should we go after the last border? Where should birds fly after the last sky?”

Darwish’s dialectic is ultimately a linguistic meditation as well as medication, synthesis and flow, memory and forgetfulness. It’s hard not to think of Paul Celan on several levels while reading “Four Personal Addresses” or, indeed, much of Darwish’s poetry. Despite the apparent difference in lyric verdancy and agency between the two, it is absence that both poets address, to its extremes:

I am my language [ . . . ]

[ . . . ] Be! Be my body! [. . .]

[ . . . ] Only my words bear me,

a bird born from me who builds a nest in my ruins

before me, and in the rubble of the enchanting world around me.

This is what Darwish says in “A Rhyme for the Odes.” He and Celan, whom he invokes in “A Cloud from Sodom,” a love poem written in 1998, were poets of loss, vanquished poets in Walter Benjamin’s sense, with language as their most assured yet most desolate possession or dispossession, their phoenix whose smoldering ashes draw in butterfly and moth. One can say a poet is an angel of history. Darwish was certainly that, and more. Through Three Poems, Paradise leads us to a window that overlooks Darwish’s early days, beyond the mutilated topography of politics, the scales of history that have rendered discourse, in Arabic and otherwise, about Darwish predictable, repetitive, expropriated: the Palestinian poet, as signifier and signified. Ibrahim Muhawi’s recent brilliant prose translation, Journal of an Ordinary Grief (2010), translates a work first published in Arabic in 1973, when Darwish was barely thirty years old. Any serious reading of Darwish’s early work, and indeed of the temporality of his gaze and flight within the storm of progress, should start with the Journal.

So what about the first twenty years or so before 1986, to which Paradise provided this serious gesture of recognition? Darwish’s story in English dates back to 1970, when an illustrated anthology of Palestinian poetry, A Lover from Palestine, titled after a Darwish poem of 1966, included a small selection of Darwish’s work. The same author and artist (el-Messeri and Boullata) would collaborate twelve years later, in 1982, and publish another beautiful illustrated anthology of Palestinian poetry, whose title was drawn from another Darwish poem, The Palestinian Wedding. In 1973 the first book fully dedicated to Darwish’s poetry in English was published. Simply titled Mahmoud Darwish: Selected Poems, it came out of the United Kingdom’s Carcanet Press. Splinters of Bone, translated by Ben Bennani, (which Edward Said quotes in his 1988 essay “Yeats and Decolonization”) followed in 1974 out of New York. A bit later, in 1980, Denys Johnson-Davies published a translation of Darwish, The Music of Human Flesh, his only poetry translation (written in the midst of his prose treasury of Mahfouz and Tayeb Salih). In 1984 Stephen Kessler contributed a rapturous rendition, from the Spanish, of Darwish’s lyric epic “From Beirut,” to Nathaniel Mackey’s journal, Hambone. Also in 1984 came perhaps the most enduring translation of Darwish’s poetry from that period: Victims of a Map (Saqi Books, UK), is an anthology that features the works of Darwish, Adonis, and Samih al-Qasim. Abdullah al-Udhari’s delicate and quenching translations include twelve of the short poems from Fewer Roses, which would not appear in book form in Arabic until two years later. Al-Udhari would go on to translate other Darwish poems in his anthology Modern Poetry of the Arab World. In fact, the four translated Darwish poems featured in Forché’s anthology Against Forgetting were originally published before 1986. The translations belong to al-Udhari and Denys Johnson-Davies.

Sand and Other Poems, a well-chosen, pithy overview of Darwish’s first twenty years of poetry, translated by Rana Kabbani, was published in 1986. Stephen Kessler republished “From Beirut” as a chapbook in 1992. In the winter of 1994, Grand Street magazine published Edward Said’s essay “On Mahmoud Darwish,” accompanied by Agha Shahid Ali’s poetic conversion of Darwish’s long masterpiece (yet another evolution of his lyric epic) “Eleven Stars Over Andalusia.” Shahid would later republish the poem in his final collection, Rooms Are Never Finished (2001), while Said’s essay remains the most important of primers on Darwish’s art. In 1995, Psalms, Bennani’s second attempt at a selected early poems, tried its luck. But the monumental event that would take place in the same year was Ibrahim Muhawi’s iconic translation of Darwish’s prose tour de force Memory for Forgetfulness. Similar to the Journal, Forgetfulness is essential reading for an understanding of Darwish’s development during the 1980s and well after. Other efforts include Banipal magazine’s feature on Darwish’s work in 1999, with an interview translated from the Arabic as the centerpiece: “There Is No Meaning to My Life outside Poetry.” Of course, the Oslo Accords had been signed in 1993 and a partial lifting of the implicit embargo on Palestinian literature in English had taken place; a new and expanded “permission to narrate,” and thus to listen, was granted, so to speak.

Naturally, it is in Arabic that Darwish’s poetry is most deeply and complexly rooted. “Rimbaud is ours,” he quipped in a poem in 1992. Darwish always bridged his glorious literary past with the brilliant literary present, away from antecedence or origins and closer to simultaneity and transposition. Dispersive plurality was his aesthetic. Understandably, however, the mention of Darwish in English brings to mind many great poets and writers, mostly European. Occasionally these parallels are reflections of the politics of balance. A proliferative reading remains necessary. If Aragon why not Auden? If Mayakovsky why not Whitman? If Donne why not Hopkins? If Yeats why not Ginsberg? If Milosz then Szymborska, et cetera. Yannis Ritsos was the first person to describe Darwish’s long poems as lyric epics, when Ritsos introduced Darwish to a large crowd in an amphitheater in Athens in 1983. There is also the case of Cavafy, whose importance to many Arab poets runs deep (is he not, in one way, also Arab?). “Other Barbarians Will Come” in Paradise is a direct example, but “the road home is more beautiful than home” is a phrase Darwish repeats and reshapes throughout his poetry. It can also be said that Darwish was in search of the Trojan poet. Does such a poet exist? Can a defeated people write great poetry, without being part of political triumph, attainment of, or adoption by, power? “Is the impossible far?” as Darwish asks in “Counterpoint,” his elegy for Edward Said. This is also the question Darwish asks in Jean-Luc Goddard’s film Notre Musique (2004), and answers earlier in “The Red Indian’s Penultimate Speech”: “Will you not memorize a bit of poetry to halt the slaughter?” And in “Mural”: “There is no nation smaller than its poem.” Or as Paradise would have it: “A nation is as great as its ode.” It’s hard not to think of Kafka writing in his Diaries: “A small nation’s memory is not smaller than the memory of a large one and so can digest the existing material more thoroughly.” It’s also difficult to imagine a poet who, in Judith Butler’s words, “gave voice more clearly to the condition of unwilled proximity”: “Darwish is thus let loose with the nameless stranger in a wilderness of uncharted lands.”

New visions of Darwish’s poetry in translation can only illuminate deeper aspects of his craft, reclaim language through the field of power that is translation. Darwish’s enduring expansion of, and experimentation in, Arabic prosody demands attention. His playful language can also serve, as nidus and nexus, to lead translation into a new expanse. Paradise also deserves credit for experimentation as a high form of tribute. Most notably, it released the circular or the folding Darwish lines into an English drive. In the unfolding, the Darwish poem in Paradise is far from domesticated. In part this is due to Darwish’s inescapable aesthetic singularity, but it is exactly the effect of this singularity that Paradise reconfigures into a beautiful vision of what a Darwish poem can achieve in and for English. Darwish himself was keen on translation as the creation of a new poem. He was keen on the translator’s freedom to “redistribute the lines” to what one deems suitable for the birth of new music. The untranslatable in poetry is more than a given, it is a precondition of translation, a vital creation of discontinuity. In Darwish’s poetry it is also a long road home. It is what translators

bestow upon the phoenix

a little of his secret’s fire

so she may kindle the lights

in the temple after him.

Fady Joudah

Houston, November 2012