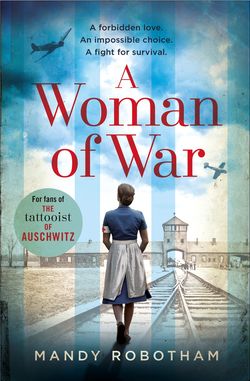

Читать книгу A Woman of War: A new voice in historical fiction for 2018, for fans of The Tattooist of Auschwitz - Mandy Robotham - Страница 13

6 Adjustment

ОглавлениеAfter the Captain left, I was alone for some time among the clutter of the housekeeper’s personal world, the room obviously doubling as her office and private sitting room, the obligatory Führer icon placed altar-like above an unlit fireplace. My stomach growled noisily, having soon become accustomed to food again, and I realised it was nearing lunchtime. I waited, since no one had issued any other instruction, and I realised how quickly I had fallen into a servile role. In the camp, it had become second nature to obey the guards as the basic rule of survival, but then to find methods of defiance in between our ‘yes, sir; no, sir’ reactions. We, none of us, ever thought of ourselves as second-class citizens, merely captives of the weapons wielded against us. Each and every day it was a fight to remind ourselves of it, but we saw it as vital, a way to avoid sinking into the mire.

Eventually, Frau Grunders entered, bringing a tray of bread, cheese and meats with her, a small glass of beer on the side. I hadn’t seen or tasted ale in over two years, and the rays of midday light created a globe of nectar in her hands. I could hardly concentrate for wanting my lips to touch the chalice and breathe in the heady hops. I had never been a connoisseur of beer, but my father would have a glass at night while listening to the wireless, and he’d let me have a sip every evening as a child, to make me ‘grow big and strong’. He was that smell, was in that glass, ready and waiting.

The housekeeper crackled as she moved, irritation sparking from her thin limbs and her crown of plaited hair as she put the tray to one side. Her mouse-like features set in a wrinkle before she spoke.

‘You will reside in one of the small annexes next to the main house,’ she began, indicating I was neither servant nor equal. ‘Unless Fräulein Braun requests that you be nearer, in which case we can arrange a cot in her room. Your meals will be in the servants’ dining room, unless Fräulein Braun wishes you to eat with her. If you need anything else, please come to me.’

I was unperturbed by her attempt at ranking; servant or not, it was about staying alive, and maintaining my own personal measure of dignity. Still, I understood that for Frau Grunders, her own self-respect lay in creating order in this strange little planet on the crest of the world, a tidy top to the chaos. With one beady eye on that beer glass, I had no reaction except a ‘Thank you,’ and she turned to leave.

‘Fräulein Braun will see you for tea at three o’clock in the drawing room,’ she said on parting. The beer was the nectar it promised to be, sweet and bitter in unison, and I choked pitifully on the third mouthful, partly through greed, but largely because I couldn’t stop the tears cascading down my cheeks, or fighting their way noisily up and through my throat.

In the camp, I had resisted dwelling on the horrors my family might be facing: whether my father’s asthma was slowly killing him; whether my mother’s arthritis had become crippling in the cold; if Franz had been shot as he stood, for that flash of dissidence his hot temper was capable of; if Ilse’s innocence was making her a target for the hungry guards. Now, amid the quiet, the comfort, the relative normality of where I sat, it cascaded from me, sobbing for the life that I, and the world, would never have again.

I felt dry as I forced down some of the bread and cheese, still not cured of camp conditioning that dictated where there was food, it must be eaten, right then and there. I gazed longingly at Frau Grunders’ bookshelves for a time, unable to move with a stretched belly and a wave of overwhelming fatigue. I yearned to finger the pages of some other world, a historical drama perhaps, to take me out of where I was. But the next thing I knew there was a gentle knocking on the door, and I opened my eyes to a young maid in her full skirt and pinafore of red and green, telling me it was past two o’clock, and enquiring whether I wanted to go to my room before meeting Fräulein Braun.

We moved on the same level from Frau Grunders’ room, through a servants’ parlour, out of a side door and onto a short gravel incline, bringing us to a small row of three wooden chalets, built on a slope so that they looked up towards the top of the house on one side, and down towards a sloping garden on the other. Mine was the middle door, with a tiny porch and patio, just big enough for a small table and chair outside the window. It was like a tiny holiday home, a place to relish freedom and the view.

The clothes Christa had adjusted were laid out on the bed; a toiletry set, fresh stockings and underwear on the drawers opposite. Next door, in the small bathroom, soap, shampoo and fresh towels were set neatly. Also laid out was a working midwife’s kit – a wooden, trumpet-like Pinard to listen to a baby’s heartbeat, a blood pressure monitor, a stethoscope, and a urine testing kit. All brand new. Guilt ran through me like lightning. What else was I expected to sacrifice for this luxury? Not just my skills, surely? Over the last two years I had faced my demons over death; I had strived to avoid it with any careless slips, but resigned, in a way, to its inevitability in all this fury. My biggest fear was in being made to choose, trading something of myself for my own beating heart, of living without soul.

In the camp, it was an easy black and white decision. It was them and us, and when favours were exchanged it was for life and death. It wasn’t unheard of for the fitter women to barter their bodies with the guards in exchange for food to keep their children or each other alive; an acceptable contract since we already felt detached from our sexuality – it was simply functioning anatomy. But information that might lead to fellow captives being dragged towards a torturous death – that was another matter. It happened, of course, when cultures were pitted against each other, but I had trusted the women around me implicitly. We would die rather than sell our sense of being.

The maid would return for me just before three, she said. I resented the time alone when she left, when I would have to think. I deeply envied those with the ability to empty their minds for some peace, to enter a blank arena with doors leading to more and more emptiness. Peace? Merely the prospect, either universal or personal, seemed utterly remote.

I found a blanket in one of the drawers and sat on the porch, basking in a winter sun slowly tipping across my face, warm and comforting. The gardens were quiet, no uniformed guards in sight, so either they were discreet, or not on full alert. I wondered if the Führer was present, and if being near to the centre of evil felt any different – whether I might sense its strength if he were near. What I would do if I came face to face with the engineer of Germany’s moral demise?