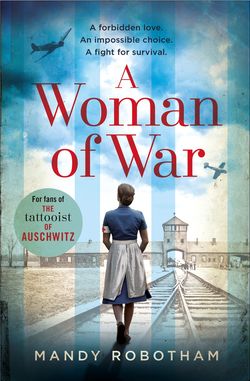

Читать книгу A Woman of War: A new voice in historical fiction for 2018, for fans of The Tattooist of Auschwitz - Mandy Robotham - Страница 14

ОглавлениеBerlin, March 1941

It was inevitable, and the one that nobody wanted: the baby of our fears.

‘Sister?’ Dahlia’s voice was already unsteady as she found me tidying the sluice.

‘Yes, what is it?’ My back still to her.

‘The baby in Room 3. It’s, erm—’

I spun around. ‘It’s what? The baby’s born, breathing?’

‘Yes, it’s born, and alive, but …’

Her blue eyes were wide, bottom lip trembling like a child’s.

‘There’s something not quite … his legs are …’

‘Spit it out, Dahlia.’

‘… deformed.’ She said it as if the word alone was treason.

‘Oh.’ My mind churned instantly. ‘Is it very obvious, at just a glance?’

‘Yes,’ she said.

‘Anything else?’

‘No, he looks perfectly fine otherwise – a gorgeous little boy. Alert, he handles well.’

‘Has the mother noticed? Said anything to you?’

‘Not yet, he’s still swaddled. I noticed it at delivery, and again when I weighed him. I’m not imagining it, Sister.’

We both stood for a minute, searching in ourselves for the answer, hoping another would hurtle through the door and provide a ready solution. It was me who spoke first, eyes directly on her.

‘Dahlia, you know what we’ve been told. What do you feel you should do?’

With such knowledge I was already complicit in any decision, but if we covered this up, would I regret it? Would it be me as the ward lead who got a visit from the hospital administrator, and the Gestapo? Or would we both bear a secret and keep it within each other? Sad to say that in war, in among the Nazis’ pure breed of distrust, even your colleagues were unknowns.

‘I’m frightened of not saying anything,’ Dahlia said, visibly shaking now, ‘but he shouldn’t be … he shouldn’t be taken from his mother. They will separate them, won’t they?’

‘I think there’s a good chance. Almost certainly.’

Dahlia’s eyes welled with tears.

‘Are you saying you want my help?’ I spelled it out. ‘Because I’ll help if you’re sure. But you have to be certain.’

We locked eyes for several seconds. ‘Yes, I’m sure,’ she said at last.

I thought swiftly of the practicalities of making a baby officially exist but disappear in unison. ‘Dahlia, you finish the paperwork and start her discharge quickly. I’ll delay the paediatrician, and we’ll order a taxi as soon as possible.’

Adrenalin – always my most trusted ally – flooded my brain and muscles, allowing me the confidence to stride into the woman’s room. I painted on a congratulatory smile, and in my best diplomatic tones I told her it would be in her best interests to leave as soon as possible, to forsake her seven days of hospital lying-in, to quit Berlin and to move to her parents’ house, where her father was dangerously ill and not expected to last the night. Wasn’t that the case? It was, wasn’t it?

She was initially stunned, but soon understood why, as we unwrapped the swaddling and she saw with her own eyes the baby who would be no athlete, but no doubt loving and kind and very possibly a great mind. I hinted heavily at his future in the true Reich, and she cried, but only as she dressed hurriedly to go home. We were taking a large gamble on her loyalties to the Führer, but I had seen enough of mothers to know all but a few would lay down their lives for their child’s survival and a chance to keep them close. Looking at her stroking his less than perfect limbs, I wagered she was one of them.

Dahlia and I took turns in guarding the door, while I forged the signature of the paediatrician on shift. He saw so many babies, and his scrawl was so poor, it would be easy enough to convince him of another normal baby if the paperwork was ever questioned.

Dahlia’s face was a mask of white, and I had to remind her to smile as we shuffled the woman out of the birth room, as if leaving only hours after the birth was an everyday scenario. The baby was swaddled tightly, with only his eyes and nose visible to the world. The corridor was clear, and we moved slowly towards the labour ward entrance, the woman taking the pigeon steps of a newly birthed mother. Dahlia assured me a taxi was waiting, engine running.

‘Are you not transferring to the ward, Sister? Is everything all right?’ Matron Reinhardt’s distinctive tones ripped through the air, stern and commanding. I swore she could silence the clipping of her soles at will.

I spun on my heels, but gave Dahlia a gentle tug on her shoulder, which meant: ‘Stay put, don’t move.’

My face fixed itself. ‘Sadly, family illness means we need to discharge this mother early, Matron. A grandfather who is keen to see the little one, as the doctors think his time is limited.’

The woman turned her head, nodding agreement, lips pursed.

Matron stepped towards us, her face unmoved. She looked quickly at the woman, turned up the corners of her mouth slightly and said: ‘My congratulations, and my sympathies.’

Then to me: ‘Is the baby fit for discharge, Sister, properly checked?’

I thought I heard a slight squeak escape from Dahlia’s direction, but it could have been the baby, in protest at being held so tightly.

My beautiful friend adrenalin came to my rescue again, pushing courage into vessels where I needed it most. I smiled broadly, and in my best officious tones, stated: ‘Of course, Matron. Fit and healthy and a confident mother with the feeding.’

She took a step forward again and aimed a long, thin finger towards the blankets around the baby’s face. Matron – who rarely touched a baby, but who directed, admired and encouraged from afar – pulled at the woollen weave and said: ‘Quite the handsome fellow, isn’t he? I hope time is on your side, my dear.’ She aimed a sympathetic smile at the mother. ‘Perhaps you’d better hurry, if you have a journey ahead of you.’

Dahlia’s face tumbled with relief, and the woman was pulled in her slipstream towards the exit. I stood with Matron and watched them go, waiting for the third degree, and her inevitable request to look at the file in my hand, to crawl over the paperwork and the fiction within. She of all people would see through my lie. A bell for one of the delivery rooms rang, and I stood unmoved.

‘Better see who wants your help now,’ Matron said, gesturing towards the room, and stepped in the opposite direction.

We never spoke of that baby or referred to him again.