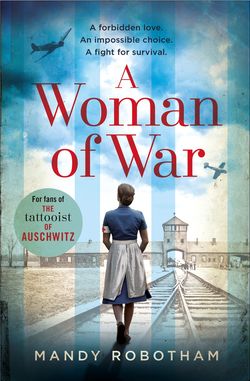

Читать книгу A Woman of War: A new voice in historical fiction for 2018, for fans of The Tattooist of Auschwitz - Mandy Robotham - Страница 15

7 Eva

ОглавлениеI must have drifted on the edge of real sleep for some time, because the maid woke me gently: Fräulein Braun was waiting. I had just enough time to check my appearance in the bathroom mirror (when was the last time I had done that?) before heading back to the main house. The corridors were eerily empty, with only shadows of bodies moving here and there. I was led into the main drawing room, vast and airy with a jade tinge, where she was waiting, dwarfed by the oversized, dark furniture. Somewhere in the background a small bird twittered, a flash of yellow in a hanging cage.

Fräulein Eva Braun stood up as I came in, offering a hand and a smile; she was average height but athletic-looking, a healthy sheen to her face and broad lips, with a touch of colour and scant make-up. Her hair was strawberry blonde, crimped and worn free, and she had on a plain, green suit – the skirt of which was strained below the waistband, its jacket barely hiding an unmistakable roundness. My eyes immediately settled on her abdomen, sizing up the gestation, while her hand instinctively went to her bump, a reaction signalling she was already attached to her baby and naturally protective. Lord knows this poor creature would need all the help it could get, a mother’s love being its best ally.

‘Fräulein Hoff,’ she said in a surprisingly small voice. ‘I am very happy to meet you. Please, sit down.’

Almost instantly, I felt that Eva Braun, mistress of Hitler or not, was no Magda Goebbels. She struck me as the girl next door, easily someone who might have worked in any of the large department stores in Berlin before the war, ready to help with a bottle of cologne in her hand. She had a potential and a smile that would have opened many a door. Maybe that’s what had charmed the most powerful man in Europe? Except I wasn’t sure if I should hate her for it.

She asked the maid for some tea, and we were soon alone. I sat without offering words, simply because I had nothing to say. There was a brief silence, split only by a crackle from the grate, and she turned squarely to face me.

‘I gather you have been told that I am expecting a baby …’ The words came out furtively, with a flick of her gaze, as if the dark, wooden walls were on alert.

‘I have.’

‘And that you were requested specifically to become my midwife. I hope that is acceptable to you.’

Possibly, she was unaware I had no real choice, of the emotional leverage involved, but still I said nothing.

‘You probably won’t know that several of my family’s friends have been cared for in Berlin during their pregnancies,’ she went on, ‘and your skills are highly thought of.’

Again, I only nodded.

‘You are also aware that, due to … circumstances, the birth of my baby—’ again she palmed her belly ‘—will be here. I want someone I can trust, who has the skills to deliver my baby safely. And discreetly. My mother was lucky enough to have the care of a good midwife several times, and I would very much like that too.’

She sat back, relieved, as if such a speech had winded her. Still, I didn’t know what to offer in reassurance. What I did know was that Eva Braun appeared, on the surface at least, an innocent. By design or sheer naivety it was hard to tell, but I couldn’t believe she had set out to sleep with a monster, let alone to carry his bastard child. The Nazi way was the family way; ‘Kitchen, children, church’ was their motto and good German wives were named as soldiers in the home, bizarrely rewarded with real medals for copious breeding. Eva Braun had broken with protocol. Her position was now untenable, her body and life no longer her own, at least while she carried the Führer’s baby – and I had to assume it was his blood, given my treatment since leaving the camp. She looked neither like a soldier nor the accomplice of evil.

Rather than feign a false delight, I focused on the pregnancy – how far along she was, when the due date would be, what types of checks she had already gone through. She had seen a doctor to confirm the pregnancy, but no one since. The dates of her menstrual cycle suggested the baby was due in early June.

‘But I’m feeling the baby move now, every day.’ She smiled, almost like a child pleasing its teacher, the hand paddling again.

‘Well, that’s a very good sign,’ I replied. ‘A moving baby is generally a happy baby. Perhaps, if you would like, I could gather my equipment and do a check, just to see if everything is progressing normally?’

‘Oh, yes! I’d like that. Thank you.’ She exuded the glow of a thousand pregnant women before her.

Confusion draped again like a thick fog, twisting the moral threads in my brain. I was supposed to feel dislike towards this woman, hatred even. She had danced with the devil, created, and was now nurturing, his child. And yet she appeared like any woman with a proud bump and dreams of cradling her newborn. I wished there and then I was back in the camp, with Rosa by my side, where the world was ugly, but at least black and white. Where I knew who to seethe against, and who the enemy was.

I collected the new equipment from my room, and Fräulein Braun led me through a maze of corridors towards a bedroom. It was mid-size, comfortable but not ornate, family pictures on the mantel – holiday snaps of healthy Germans enjoying the outdoors. In all, there were three doors to the room: one we had come through, another leading to a small bathroom, and, on the opposite side, one linking to a second bedroom. I glimpsed a double bed through a crack in the doorway, a heavy brocade covering. She caught me looking and closed it quietly. And then it hit me. Was that his room? The leader of all of Germany, engineer of my misery, all misery at this point? Instantly, I wanted to find an exit from this surreal normality, but Fräulein Braun – my client – was already standing by her own bed, waiting.

‘Do you want me to lie down, Fräulein Hoff?’ Her face was full of expectation, of hope.

There were times in my career when I hated the automatic elements of midwifery. Early on, some of the labour wards in the poorer district hospitals had seemed like cattle farms – one abdomen, one baby after another. But now, I was thankful to my training, piloting my way through the check. With her skirt lowered, Eva Braun was any other woman, a stretching sphere to be assessed, eager to hear her baby was fit and healthy.

I pressed gently into the extra flesh she was carrying, kneading downwards until I hit a hardness around her navel. ‘That’s the top of your womb,’ I explained, and she gave a small squeak of acknowledgement. I pressed the Pinard into her skin and laid my ear against its flat surface, screening out the sounds of the house and homing in on the beating heart of this baby. She remained stock still and patient throughout – and I finally caught the edge of its fast flutter, only just audible, but the unmistakable rate of a galloping horse.

‘That’s lovely,’ I said, bringing myself upright, ‘a good hundred and forty beats per minute, very healthy.’

Again, her face lit up like a child’s. ‘Can you really hear it?’ she said, as if Christmas had come early.

‘The baby’s still quite small,’ I said, ‘so it’s very faint, but I can hear it, yes. And everything feels normal. It seems to be progressing well.’

She stroked the bump again and smiled broadly, muttering something to the baby under her breath.

We talked about how often she might want a check, when we would start planning the birth, if she might take one last trip to see her parents – a good day’s drive away. I realised I would be redundant for much of my time at the Berghof, amid this luxury, and the intense guilt rose up again. As I turned to go, she called behind me: ‘Thank you, Fräulein Hoff. I do appreciate you coming to care for me.’

And I believe she meant it, innocent or not. I didn’t know whether to be gracious for my life chance, or angry at her naivety. A thought flashed, ‘a child within a child,’ and I forced a smile in response, while every sinew in me twirled and knotted.