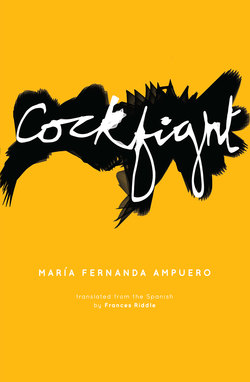

Читать книгу Cockfight - María Fernanda Ampuero - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеMONSTERS

Narcisa used to say that we should be more afraid of the living than the dead, but we didn’t believe her because in all the horror movies we saw, we were most afraid of the dead, the ones that had returned from beyond, the possessed. Mercedes was terrified of demons and I was terrified of vampires. We talked about it all the time. About satanic possessions and about men with fangs who fed on the blood of little girls. Mom and Dad bought us dolls and books of fairy tales, and we reenacted The Exorcist with the dolls and made believe that Prince Charming was really a vampire who woke Snow White up to turn her undead. During the day everything was fine, we were brave, but at night we always asked Narcisa to stay upstairs with us. Dad didn’t like Narcisa sleeping in our room—he called her the help—but it was inevitable: we told her that if she didn’t come up, we’d go down to sleep with the help in her room. That seemed to terrify her. And so Narcisa, who must’ve been about fourteen years old, tried to protest, saying that she didn’t want to sleep with us, that we should be more afraid of the living than the dead. And we thought it was ridiculous because how could anyone be more afraid of Narcisa, for example, than of Regan, the girl from The Exorcist, or more afraid of Don Pepe the gardener than of the Salem vampires or of Damien, the Antichrist, or more afraid of Dad than of the Wolf Man. Absurd.

Mom and Dad were never home—Dad worked and Mom played bridge with neighbors—that’s why Mercedes and I could go rent horror movies at the video store every day after school. The boy who worked there never said a word to us. We knew that the cases said over sixteen or eighteen, but the boy never said anything. His face was covered in zits and he was fat, he always had a fan pointing at his crotch. The only time he ever talked to us was when we rented The Shining. He looked at it, then looked at us, and said:

“There are some girls just like you in this. Both of them are dead, their dad killed them.”

Mercedes grabbed my hand. And we stood there like that, holding hands, in our matching uniforms, staring at him until he gave us the movie.

Mercedes was a big scaredy-cat. Pale, sickly. Mom said that I must’ve eaten up everything that came down the umbilical cord because she was tiny when she was born, a little worm, and I, on the other hand, was born like a bull. That’s the word everyone used: bull. And the bull had to take care of the worm, who else would? Sometimes I wished I could be the worm, but that was impossible. I was the bull and Mercedes the worm. I’m sure Mercedes would’ve liked to be the bull sometimes, not always tagging along in my shadow, waiting for me to say something so that she could simply agree: “Me too.”

Never me. Always me too.

Mercedes never wanted to watch horror movies, but I made her because a girl from school said I wasn’t brave enough to watch all the movies she’d seen with her big brother since I didn’t have a big brother—only Mercedes, the infamous scaredy-cat—and I couldn’t stand it, so that afternoon I dragged Mercedes to the video store and we rented all the Nightmare on Elm Street movies, and that night and every night after, we had to tell Narcisa to come upstairs to sleep with us because if Freddy gets in your dreams he kills you in your dreams and no one knows what happened to you because it just looks like you had a heart attack or choked to death on your own drool—something “normal”—and so no one ever finds out that you were actually killed by a monster with knives for fingers.

Having siblings can be a blessing. Having siblings can be a curse. We learned this from the movies. And we learned that one sibling always saves the other.

Mercedes started having nightmares. Narcisa and I did everything we could to keep her quiet so Mom and Dad wouldn’t find out. They would punish me: horror movies, so obviously the bull’s fault. Poor little worm, poor little Mercedes, to have such a beast of a sister, a girl so unlike a girl, so wild, what a cross to bear. Why aren’t you more like little Mercedes, so sweet, so quiet, so gentle?

Mercedes’s nightmares were worse than any of the movies we watched. They were about school, the nuns, the nuns possessed by the devil—dancing naked, touching themselves down there, appearing in the mirror while she was brushing her teeth or taking a shower. The nuns, like Freddy, taking over her dreams. And we’d never even rented a movie like that.

“What else happened, Mercedes?” I asked, but she didn’t say anything, she just screamed.

Mercedes’s screams penetrated my skull. They sounded like howls, gashes, bites, animal things. Her eyes were open but she was still somewhere else, and Narcisa and I hugged her so she would come back but sometimes coming back took her a long time, and I thought, once again, that I was stealing something from her, just like when we were in Mom’s belly. Mercedes started to get really skinny. We were identical, but less and less so, because I was becoming more and more like a bull and she was becoming more and more like a worm: sunken eyes, hunched, bony.

I never had much love for the Sisters at school nor they for me. In other words, we hated each other. They had a radar for unruly souls, that’s the term they used, but I didn’t mind, I liked the sound of it. I hated their hypocrisy. They were bad people dressed up as good ones. They made me erase all the school’s blackboards, clean the chapel, help Mother Superior distribute alms—which was just handing out what other people (our parents) had given to the poor, the middlewoman keeping a bunch for herself, eating expensive fish and sleeping on a feather mattress. It was punishment after punishment for me because I asked why they gave out rice to the poor while they ate sea bass and I told them the Lord wouldn’t have liked that because he made the fish for everyone. Mercedes squeezed my arm and cried. She knelt down and prayed for me with her eyes closed tight. She looked like a little angel. While she recited the Hail Mary, I wanted to make everything else stop dead because I felt like my sister’s prayer was the only thing worth anything in this fucked-up world. The nuns told my parents that my sister would be perfect for their order, and I imagined her life spent locked away in that prison of horrible clothes and giant crucifixes like shackles: I couldn’t bear it.

That summer we got our periods. First Mercedes, then me. Narcisa was the one who taught us how to use pads because Mom wasn’t there, and she laughed when we started waddling around like ducks. She also told us that our blood meant that, with the help of a man, we could now make babies. That was ridiculous. Yesterday we couldn’t even imagine doing an insane thing like creating a child, and today we could. “That’s a lie,” we told her. And she grabbed us both by the arms. Narcisa’s hands were very strong, big, masculine. Her fingernails, long and pointy, could open sodas without a bottle opener. Narcisa was small and just two years older than us, but she seemed to have lived four hundred more lives. Our arms burned as she repeated that now we had to beware of the living more than the dead—that now we really had to be more afraid of the living than of the dead.

“You are women now,” she said. “Life isn’t a game anymore.”

Mercedes started to cry. She didn’t want to be a woman. I didn’t either, but I’d rather be a woman than a bull.

One night, Mercedes had another one of her nightmares. There weren’t nuns anymore, but men, faceless men who played with her menstrual blood and rubbed it all over their bodies, and then from everywhere monstrous babies appeared, like little rats, to gnaw her to death. I couldn’t calm her down. We went to look for Narcisa, but her door was locked from the inside. We heard noises. Then silence. Then noises again. We sat in the kitchen, in the dark, waiting for her. When the door finally opened, we threw ourselves at her, we needed her arms so badly, her hands that always smelled like onion and cilantro, her healing words saying we should be more afraid of the living than the dead. A few inches away, we realized it wasn’t her. We stopped, terrified, mute, frozen. It wasn’t Narcisa who had come through the door. Our hearts ticked like bombs. There was something both foreign and familiar in that silhouette, filling us with disgust and horror.

I was late to react, I didn’t have the chance to cover Mercedes’s mouth. She screamed.

Dad slapped each of us across the face and then walked calmly up the stairs.

Neither Narcisa nor her things were in the house the next morning.