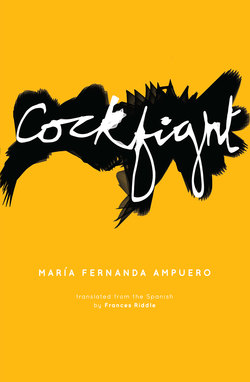

Читать книгу Cockfight - María Fernanda Ampuero - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеGRISELDA

Miss Griselda made amazing cakes.

She had binders filled with photos of the most beautiful cakes in the whole world. It was always the cake, not the new dress. The cake, not the colorfully wrapped gifts. The cake, not the delicious food, that was the highlight of every birthday party: choosing it and imagining all the guests’ jealous faces as they saw how awesome our birthday cake was.

The thing was, Miss Griselda’s cakes weren’t round like everyone else’s. They were shaped like Mickey Mouse, a dollhouse, a fire truck, Winnie the Pooh, the Ninja Turtles.

Miss Griselda’s cakes weren’t white with colored sprinkles like the ones my mom made, or caramel or chocolate like the ones you saw at the other birthday parties. No way. If it was a taxi, the cake was taxicab yellow; if it was a police car, it had everything including the red lights of the siren; if it was a soccer ball, black and white; if it was Cinderella, it had everything down to her blond hair and glass slippers, even the brown mice.

Miss Griselda made unforgettable cakes. She made my brother’s First Communion cake in the shape of an open Bible, and on the pages made of sugar she wrote in little gold letters: There is nothing more perfect than Love. Love always protects, always trusts, always hopes, always perseveres. People couldn’t stop asking my mom where she’d gotten such an amazing cake, and they took pictures of it instead of my brother. Or rather, they took pictures of him, but always with the cake. Mom told Miss Griselda. She blushed, she looked happy.

When it was almost our birthdays, all the kids in the neighborhood would go over to Miss Griselda’s after harassing our mothers for days, our stomachs churning with excitement. Finally the moment would come when she would give us her stack of binders and tell us ceremoniously: “Pick whichever one you want. Take your time.” Her eyes shone as she waited for us to point to the chosen one.

“This one.”

We began to turn the pages. The decision, that terrible moment. And our brothers and sisters always interfering: “Mommy, I want this one for my next birthday,” “Mommy, I want her to make me a cake too.” We had big fights. Once, we argued so much that Mom got two cakes for my party: one that looked like R2-D2 and another that looked like Strawberry Shortcake.

While we decided, my mom would ask after Miss Griselda’s health, about her daughter Griseldita, about her plants. But never about her husband. People said that her husband had gone off with another woman. Or that one day he went to work and never came home. Or that he was in prison. Or that he beat her so badly she ended up in bed for days and she threatened to call the police. Or that he had kicked her and her daughter out of the house and they’d had to come here. I knew the house well because my friend Wendy Martillo had lived there before her parents got divorced.

Even though it was the same house, Miss Griselda’s place was very different from my friend Wendy Martillo’s. Maybe it was all the very large and very dark furniture in the tiny living room, or maybe it was the thick curtains that were always shut tight. Miss Griselda’s house smelled stale, old, dusty. But none of that mattered, because all you had to do was open one of her binders and it was all bright colors and Disney characters, Barbies, Spider-Man, soccer fields with green-sugar grass, candy goalposts, and cookie-crumb players, hearts, teddy bears, baby booties, treasure chests filled with chocolate coins—anything we could ever wish for on a cake.

Miss Griselda didn’t make a living doing this. Actually she didn’t charge much at all because everyone in the neighborhood was broke. Her daughter, Griseldita, was the one who supported them. It seemed like she was doing pretty well. She’d gotten two new cars and always wore new clothes. She bought entire suitcases of items from Miss Martha across the street, who brought things from Panama, and it was this woman who spread the rumor that Griseldita was in with a wayward crowd. That’s how she said it: “a wayward crowd.” Griseldita was blond, very white, and she always wore heels that made her look really tall. She came home at four in the morning a lot, making a ton of noise screeching her brakes, jangling her keys, and click-clacking her heels. What no other woman in the neighborhood would do, Griseldita did.

One day we went to pick out the cake for my eleventh birthday, and as soon as we got inside, my mom, who was in front of me, sent me back outside. But I got a glimpse. Miss Griselda was lying on the floor, her robe askew, her panties showing, and she looked dead. I screamed. My mom was furious, and she sent me home. Then a little later I saw Miss Martha run across the street, then Miss Diana and Miss Alicita. Then the whole block was out on the street. They were shouting for Don Baque, the neighborhood watch, to come help. We peeked out the windows in spite of our mothers’ shouted threats.

It seemed that someone had called Griseldita because she arrived shortly, more angry than afraid, and shooed away all the women who had surrounded her mother. She shrieked like a madwoman for all the nosy old ladies to get out, that there was nothing wrong, shitty old ladies, to mind your own business, you bunch of old whores, don’t you have your own houses, you bunch of old bats. Miss Martha stood on the sidewalk murmuring, “The nerve of that girl, her calling us whores. And while we’re helping her mother.”

My mom was the first to come home because she didn’t like all the ruckus. She said just that: “I don’t like all the ruckus.” She had blood on her hands, and we got scared and started to cry. “Miss Griselda fell down, everything’s fine, she’s all right, she slipped because she’d just mopped the floor.” Later I heard her talking to the other women. Miss Griselda smelled of alcohol, Mom told them, she’d fallen down and busted open her forehead. She was covered in vomit, Mom whispered, and dirty. The other women said that Griseldita might have hit her, that she beats her senseless. They repeated “senseless.” My mom didn’t believe it. No way, how could a daughter do that to her mother, that’s atrocious, no way, no way. The other women said it was true, it was true. And that both of them hit the bottle hard, they hit it hard. They repeated, “They hit the bottle hard, they hit it hard.” And that when she came home drunk, she beat her mother. Or when she found her mother drunk, she beat her. That when she was sober, she beat her mother. That it was an everyday thing.

That year on my eleventh birthday, I didn’t get my cake. Mom didn’t want to order it from Miss Griselda after all that, so we had a sad sponge cake covered in white meringue, Agogó candies for sprinkles, and a candle shaped like the number eleven. Mom promised me that I would have the most spectacular cake in the world for next year, and I started picturing a super tall, super blond Barbie with a crown and a pink princess dress with silver ruffles, all made from layers of cake with caramel in the middle. Miss Griselda would make me the most beautiful Barbie cake in the world. I could already see it, so perfect, in the center of the table. My classmates would die of envy. Bam, bam, bam. One after another, like cockroaches sprayed with Baygon.

That Christmas was brutally hot, and half the neighborhood was already out on the street when we heard the gunshot. Boom. Like a thunderclap. Bats took off with terrifying squeals. Dogs started barking. Everyone crowded in front of Miss Griselda’s house, but no one dared go inside.

Some police officers brought her out wrapped in a white sheet that was getting soaked with more and more blood, the stain only growing.

“What did Doña Griselda do?” my mom cried. “Or what if it was her daughter?” Miss Martha gasped. And they covered our eyes and sent us home, but none of us went. We just stood a little farther away. The lights from the police car went round and round. Everything was red. In the distance Christmas firecrackers were going off. And the stain kept growing, growing, growing, and a hand escaped from under the sheet. Just one hand, like she was saying, “Ciao, you guys have to stay here.”

A few days later a truck came to take away all of Miss Griselda’s furniture and a bunch of boxes of her stuff, the cake binders too, I guess. Her daughter left the neighborhood that same day. We never saw her again.

I had shitty round cakes for my birthday the next few years, but honestly, I didn’t give a damn about cakes anymore.