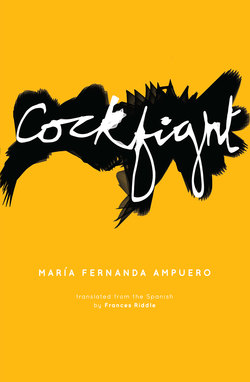

Читать книгу Cockfight - María Fernanda Ampuero - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеNAM

She’s getting naked. Something either very bad or very good is happening. Happening to me. Whatever it is, my parents can’t find out. I’m at a friend’s house. Nothing strange there. But my new friend, halfgringa, half-Ecuadorian, is taking off her uniform, her sports bra, her thong, her shoes. She leaves on her socks, short ones, with a little pink ball at each heel. She’s naked, her back to me, staring into her closet.

It’s awkward and dazzling. Painful. My head down like an ashamed dog, an ugly, short-legged dog, I try to look the same as I did a moment before, when we were both dressed, when that image, the one of her body, hadn’t exploded like a thousand fireworks in my brain. Diana Ward-Espinoza. Sixteen years old. Five-foot-nine. Star player on her high school volleyball team in the United States. Green cat eyes, radioactive. The bright white smile of the people from up there.

Diana, pronounced Dayana in gringo, talks and talks, always, nonstop, mixing English and Spanish or making up a third language, hilarious, making me squeal with laughter. With her, I laugh as if there were nothing wrong at home, as if my dad loved me like a dad. I laugh as if I weren’t me, but some girl who slept peacefully. I laugh as if cruelty didn’t exist.

She repeats the words the teachers say like tongue twisters, and never gets them right. Maybe because of this, because they think she’s dumb, or because she lives in a little apartment and not in a majestic house, or because her mom is the English teacher at school and so she doesn’t pay tuition, or because she jogs through the neighborhood in tiny shorts, blue with a white line that makes a V on her thighs—because of all that, or because of some obscure hierarchical logic made up by the popular girls, no group has accepted her. She’s blond, white, she has green eyes, her tiny nose is dotted with golden freckles, but no group has accepted her.

They haven’t accepted me either, but with me it’s the same as always: fat, dark, glasses, hairy, ugly, strange.

One day our last names are paired up in computer class. One right next to the other. It’s everything. I learn that BFF means Best Friends Forever.

Then we’re best friends forever. Then she invites me to her house to study. Then I tell my mom I’m going to spend the night at Diana’s. Then we’re in her tiny room and she’s naked. She turns around to cover her cream-colored body with a denim dress. She turns on music. She dances. Behind her, a gigantic American flag on the wall.

Covered in a fine white fuzz, her skin has the appearance, the delicacy, of a peach. She talks about boys (she likes my brother), about the exam we have the next day (philosophy), about the teacher (he’s funny, but what the fuck is being?). About how she’s never going to understand things like I do, about how I’m the smartest person she’s ever met, and about how she, okay, let’s be honest, she’s good at sports.

She stops in front of the mirror, less than a few feet away from me, on her bed, pretending to be absorbed in our philosophy textbook. If I wanted to, and I do, I could reach out my index finger and touch her hip bone, sliding down to where her pubic hair starts (I’ve never seen golden pubes), and find out if what glimmers there is wetness.

She ties up her Mary-had-a-little-lamb ringlets, she smears her lips with a gloss that smells like bubble gum, and she complains about her hair, her ears, a pimple I say I can’t see. But I can’t look at her, and she notices, and she pouts: “You’re not even looking at me, stop studying, you already understand what being is.”

She grabs my chin and raises my face to make me look at her. I smell the bubble gum on her lips. I hear my heart beating. I stop breathing.

“See this pimple? Here? Do you see it?”

My tongue is stuck to the roof of my mouth. I swallow sand. I nod.

We have lunch with her brother Mitch, her twin, who is so handsome that my jaw falls open when I have to talk to him. He was just at soccer practice. He takes off his sweaty shirt and doesn’t put on a new one. We eat alone, like a family of three. Diana sets the table, I pour the Coca-Cola, and Mitch mixes sauce into a pot of pasta.

I suppose that their parents, both of them, are working. I know that Miss Diana, their mom, my English teacher, has another job in the afternoon at a language school. I don’t know anything about their dad. I don’t ask. I never ask about dads. They tell me that Miss Diana leaves food for them in the morning, that she isn’t a good cook. It’s horrible. We smother our plates in Kraft parmesan cheese and laugh hysterically.

Mitch has an exam too, but he doesn’t want to study. In the dining room, which is also the living room, there are photos on the walls. Mitch and Diana, little, dressed as sunflowers. Miss Diana, thin and young, in front of a house with a mailbox. A black dog, Kiddo, next to a baby, Mitch. The kids at Christmas, surrounded by presents. Miss Diana pregnant. Diana, in white, at her First Communion.

There’s something sad in these photos, something in the lighting, typical of gringo photos from the seventies: maybe too many pastel colors, maybe the distance, maybe everything that isn’t pictured. I feel a sadness that doesn’t belong to me. Mine is still there, but this is a different one. This life—the sunflower children, the beautiful baby beside the black dog, everything that looks so perfect—isn’t going to turn out very well. No. Despite their blond heads, their athletic bodies, their pink cheeks, and their bright eyes, it’s not going to turn out very well.

There’s something desperate, somber, about Diana, about Mitch, about me, about this little apartment where three teenagers are sitting on the floor listening to music.

We play records: the Mamas and the Papas, the Doors, Fleetwood Mac, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Jimi Hendrix, Bob Dylan, Simon & Garfunkel, the Moody Blues, Van Morrison, Joan Baez.

Diana tells me how her parents went to Woodstock and she pulls out a photo album where, finally, there’s a picture of her father. Mr. Mitchell Ward: red mustache, long hair tied with a headband. Ultra gringo, as big and beautiful as his kids, looking at a girl, Miss Diana, almost unrecognizable, so smiling, so natural.

Then, behind that page, there’s another photo that makes us all go silent: the dad, dressed as a soldier—Lieutenant Mitchell Ward.

“He went to Vietnam.”

The two of them, Diana and Mitch, say the words at the same time, like a single person with a voice that is both masculine and feminine: “He went to Vietnam.”

He went to Nam.

Nam.

The shadow reemerges, that suffocating lack of light, silence like an angry sea. The three of us hug our knees and look at the record player. The Doors play, we like them. We sing a little, and Diana translates: People are strange when you’re a stranger / Faces look ugly when you’re alone. Mitch puts on Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks, and during the song “Madame George,” I lie down across Diana’s legs. Mitch rests his head on my stomach. We play with one another’s hair.