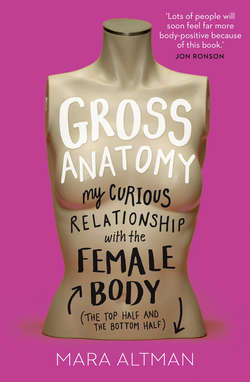

Читать книгу Gross Anatomy - Mara Altman, Mara Altman - Страница 12

3 Face It

ОглавлениеA friend once told me that I look exactly like Matza Ball Breaker, a girl on the Chicago roller derby team. She called our resemblance “uncanny.” So I searched for Matza Ball Breaker on the internet. When I saw her, I was mystified. We both have hair on our heads and a chin below our mouths. We could also both claim a set of eyes. Most likely, she, like me, had a vagina as well. Other than that, I was left deeply confounded. My supposed doppelgänger looked nothing like me—or at least the concept of me that exists in my head.

Even though I’ve seen my image—photos and reflections—for thirty-four years, I’m confused as to which—if any—portrays reality. How I appear to myself is not at all consistent; my image is like a moving piece of newsprint that I can never fully read.

The me that I see in the mirror is often, though not always, more attractive than the me I see in photographs. When I see photos, it feels as though I must have been kidnapped as the shutter tripped and had Yoda placed in my stead.

There is nothing worse (except for murder, of course, and finding a long wiry hair in your entrée) than hearing someone say, “That’s a great photo of you,” only to get a glimpse of it and see staring back at you a mustachioed gnome with water-balloon cheeks and a grimace that could stunt-double for an elephant’s anus. If that is a “great” photo, then what am I when I’m captured at my everyday?

I’ve tried to get a handle on this discrepancy by pointing at various disagreeable photos of me and asking my friends, “Is that really what I look like?”

Then it’s often discouraging when they say, “Yes.”

In order to survive, I have to tell myself that everyone—all the people in the world—must be way overdue for cataract surgery.

No matter how sure I am, my perceptions are inevitably challenged. Recently, I snapped a selfie that I liked—there I am, I thought after taking my twenty-fourth shot—so I asked Dave for validation.

“How about this?” I said full of hope. “Is that what I look like?”

“Yes,” he said.

I was elated until he quickly added, “Except for your face is much rounder and your cheeks are bigger.”

Thus, the various manifestations of my appearance continue to confound me.

I was always uncomfortable with the author photo on my first book, but not for the usual reasons. This photo actually promised a little too much—unlike most, it didn’t make me look entirely like an Ewok—but friends and family reassured me that it was a fair depiction.

I spent many months going to events with a fear that I’d sense a palpable disappointment upon the audience’s realization that the real me didn’t live up to the poster outside. Everything was okay—if it was happening, people kept their snickering to themselves. I felt encouraged—perhaps I actually was attractive—until a loathsome evening in the middle of June at a small event space in Midtown Manhattan.

Before the reading, a woman lingered in the back by the table of books. She had my book in her hand and was rifling through the pages. She nonchalantly asked me who I’d come to see.

“I’m actually reading tonight,” I told her.

“Which book?” she asked.

I told her it was the one in her hands.

She turned the book over and appraised the photo. “Oh, that’s you?” she asked. I sensed a bit of incredulity.

“Yes,” I said.

She laughed and gave me a knowing glance. “I have some glamour shots, too,” she said.

After all the evidence—the misleading doppelgängers, the fickle photos, and the many unreliable reflections that chase me around the city in storefront windows—all I can say about my appearance with any certainty is that I have brown hair, a mouth, and a couple of ears. I’ve been wondering about it for years, so I finally wanted to know, why is it so difficult to get a real read on our own appearance? Is there a true version of the self, and if so, can we ever see it?

At first, I suspected that the inconsistency I experienced with my looks was solely an issue with the medium I used to view myself. There was something mysterious that happened—I became uglified—when my image hopped from a reflection to a photograph. Cameras, those bastard devices, had always misunderstood me.

To fill me in on what might be happening, I spoke with Pamela Rutledge, the director of the Media Psychology Research Center. She said what many of us might already know: The mirror is a small white lie. It flips our image. Unless our faces are perfectly symmetrical—which happens only in the rarest of supermodel cases—we will likely feel uneasy when we see a photograph of ourselves. The nose that usually leans to the right in a photo leans to the left.

“It can look slightly off and therefore look funny to us,” Rutledge said. She explained that many of us prefer our mirror self simply because we see it more often. “We like what’s familiar,” she said.

“We like what’s familiar” sounded like an off-the-cuff generality, but it’s actually science. We tend to develop a preference for things—sounds, words, and paintings—for no other reason than that we are accustomed to them. This concept, called the Mere Exposure Effect, was proved in the 1960s by a Stanford University psychologist named Robert Zajonc. (Finally, there’s an answer to the shoulder-pad craze of the 1980s. Just by being repeatedly exposed to something—even if it’s heinous—you can come to think of it as a good-looking fashion statement.)

Another issue with the mirror is that we all, unconsciously, shift into flattering positions—hide the double chin, suck in the stomach, pop the hip—but it takes only one candid photo to haunt all that hard work and make you second-guess everything. I thought my arms were svelte little hockey sticks until a camera came along at an angle I was unaccustomed to and captured them in a way that gave me a month of night sweats.

Photographs, like mirrors, also don’t tell the whole truth. Depending on lighting, focus, and lens size, they can distort us in various subtle ways.