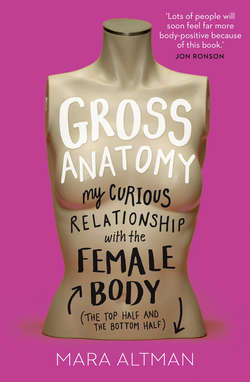

Читать книгу Gross Anatomy - Mara Altman, Mara Altman - Страница 8

Prologue

ОглавлениеTo become a master at any one thing, it is said that one must practice it for 10,000 hours. I have been living in my body for 306,600 hours, yet I still feel like a novice at operating this bag of meat. As soon as I feel like I’ve got everything figured out, something changes—boobs spring out of my chest, I sprout a mustache, floaters homestead in my eyeballs—and I’m left shocked, bewildered, and yet ultimately quite curious. I cannot tell you the number of times I’ve wondered, especially after a spicy meal, why evolution wasn’t smart enough to build us with buttholes made out of something more durable. Lead piping, perhaps?

I’d like to say that I spend my time trying to cure cancer, eradicate hunger, and put an end to global warming, but my brain is naturally inclined toward questions about the human female body. I spend most days wondering about the potential aerodynamic advantages of camel toes and why, when we are built to sweat, I often find myself hiding in a public restroom, drying off my pit stains to pretend that I don’t have glands. Why does my dog, every time I squat down, make a beeline for my crotch? The only other thing she’s drawn to with such consistency is the garbage can.

I want to be one of those people who, in the morning, sip an espresso while filling in the New York Times crossword puzzle—what a respectable hobby!—but instead I’m busy wondering why, as I hump, I never sound nearly as cool and moany as the porn star Sasha Grey in the film Asstravaganza 3. Is there a meet-up group for sex mutes?

Let’s, for a moment, suspend the idea of self-accountability and attempt to blame these bodily fixations on my parents. They grew up during the 1960s and were the kind of hippies who were so hippie that they refused to be called hippie. “Hippies were so conformist,” my mom has always told me.

My parents first met in high school and then dropped out of UC Berkeley together. They began growing plants—mostly cacti and succulents—in their backyard and then, to make a living, sold them to local grocery stores and via mail-order catalogues.

My mom never wore any image-altering materials—no makeup, deodorant, perfume, push-up bras, or high heels. She has refused antiaging creams and would never dream of fillers. (When she read this, she said, “What are fillers?” Sheesh!) She didn’t even shave her legs or armpits, and still doesn’t to this day. I thought all that was normal female behavior until late elementary school, when I noticed that other moms didn’t have a great black muff under their arms when they waved their children in from the playground. I imagined that astronauts could spot my mom from space. “Houston, we have a problem—there appear to be two errant black holes near San Diego’s suburbs.”

While I felt proud of her uniqueness, I also felt terrified of being ridiculed because of it. I explained to her that it was perfectly possible to wave at me less zealously while gluing her elbow to her side.

So for a long time, I didn’t know a lot of woman things. In my twenties, I thought that women tipped the wax lady to keep her quiet.

My father, meanwhile, turned his nose up at anything he deemed unnatural. He hated perfume and artificial scents of any kind. When I tried a spritz of my friend’s bottle of White Musk from the Body Shop, he screwed up his face and rolled the car windows down. When he caught me wearing lipstick, he looked at me like I’d just murdered a giant cuddly panda bear to use its innards as war paint.

Growing up, I had a different concept of femininity. I came to think that artificially enhancing my appearance in any way showed a lack of self-acceptance, that it meant I wasn’t strong enough to be who I really was. All the girls out there who were wearing makeup, dyeing their hair, and covering their stink were frauds. I, who stepped forth into the world doused in her artisanal BO, was real. Of course, keeping it real doesn’t mean that I didn’t often feel uncomfortable. I found myself in a constant battle between self-righteousness and shame. Eventually I learned that one’s identity can be complemented, not always concealed, by how one chooses to express oneself superficially.

Ultimately, I matured in an environment that made me hyperaware of our social norms because I was constantly conscious of how I was never managing to meet them. Though I now partake in many of the beauty practices that I grew up shunning, maybe it’s because of my upbringing that I always catch myself asking, “But why?”

Then again, I’m not sure I can blame my parents for everything. Their aversion to razors probably doesn’t account for why I spent the last couple of days mining modern literature for hemorrhoid references or spent an hour unwinding after a rough week by watching Dr. Pimple Popper’s blackhead-extraction videos on YouTube.

In any case, I’m not saying that I’ve got it together more than any other woman; it is precisely my own volatile and apprehensive relationship with my own body parts, such as my bowels, bunions, belly button, and copious sweat glands, that has compelled me to go forth in search of answers from everyone from the goddess worshippers of Bainbridge Island to the top lice experts in Denmark.

This book won’t cure a bad hair day or a yeast infection, or anything else for that matter, but it is my hope that by holding up a magnifying glass to our beliefs, practices, and nipples, this book might serve as a small step toward replacing self-flagellation with awe, shame with pride, and vag odor with, well, vag odor is kind of inevitable. But get this, PMS might actually be a superpower!