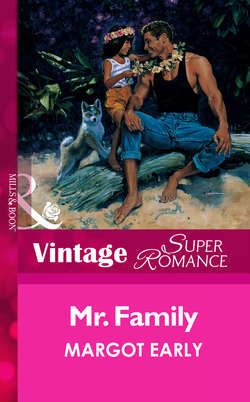

Читать книгу Mr. Family - Margot Early, Margot Early - Страница 10

CHAPTER THREE

ОглавлениеMalaki: March

TO ERIKA’S DISAPPOINTMENT, Adele expressed misgivings about Poofie and Free Kittens. Good work, she said gently, but not enough universal appeal for a print series. How about something with people in it?

Erika was painting people now, but nothing she could sell: Six similar paintings, not just in watercolor but also in acrylic and oil. Two of the subjects had come from an incomplete photograph. The third eluded her and stood ghostlike on the side.

Maka, she thought, who are you?

She had shaped each different Maka using pictures of hula dancers from Hawaiian travel magazines, which now lay all about her studio. She had used no one model but had combined different characteristics.

What had Maka been doing? Was her other arm behind Kalahiki, holding him? Was her face turned up to his? What was she wearing? How tall was she? Her right arm was medium-size and well-toned—

The phone rang.

Erika had trained her heart not to leap at that sound, and now she debated letting the machine pick it up to prove her self-control. Ever since she’d received Kalahiki’s letter—and answered it—she’d been unsteady. She shouldn’t care so much. But she did. About a broken-hearted man she didn’t know. Twenty times a day, Erika laid those feelings aside, put them in the place where she put her reaction to his picture, a reaction that was all wrong.

Kal’s grief was his business, not hers.

That he looked like an engraved invitation to come to Hawaii and fall in love was irrelevant.

A celibate marriage was exactly what she wanted. A husband. A child. And no physical complications, no difficult intimacy.

She could keep her head, not get involved. It was easy when she remembered what doing otherwise could mean. Sex.

Yuck.

So he was hung up on his dead wife. Good. He could have his hang-ups; she’d keep hers.

The telephone rang again. She should answer. Adele was back from Hawaii. This might be something about work. Like what? She’s already rejected all my paintings.

The phone rang a third time. Erika set down her brush, dropped down to the shadows of the galley and picked up the receiver. “Hello?”

There was a silence, like a punctuation mark. Then, “Hello. This is Kal Johnson calling. Is Erika there?”

She sank down on the steps of the companionway. With a slight breeze from the open hatches blowing her oversize T-shirt against her back, she clutched the receiver. His voice was low and resonant. Masculine. Unique.

God help her.

Sexy.

“This is Erika.” She was in a vacuum and her insides were being sucked out of her. She heard the engine of a cabin cruiser crawling past in the harbor, and a slow wake rocked the junk at its berth.

“I’m not sure if you know who I am, but—”

“I know who you are. You’re Kalahiki.”

Across the Pacific, in the sun-dappled morning shadows inside the bungalow, Kal heard her say his name for the first time. At the same moment he saw Hiialo outside beating Pincushion against the porch. “Bad Pincushion! Bad! No talk stink!”

What had Pincushion said?

“I thought we should talk on the phone.” Brilliant, brilliant, keep it up, Kal.

Erika bit her lip. There was a bellows stuck in her throat, and it was opening and closing with each beat of her heart. Talk, she thought. Say something that will make him…

Oh, she wanted it. They could settle into permanencepermanent celibacy, permanent family—and her life would not change again. Safe.

“Your daughter’s beautiful.” The ensuing pause was so long that at last she asked, “Are you still there?”

“Yeah. I…Erika…”

Silence surrounded her name. Silence…and feeling. It was so dark in the galley she didn’t know why her eyes burned that way, why she felt so—

“I just wanted to tell you some things,” he said. “I’ve thought a lot since I got your letter. Are you serious about this?”

Erika swallowed. This. As though he couldn’t say it himself.

“Yes.”

“My house is small. It’s a bungalow. I could fix it so we’d have our own rooms, but it’s still cozy. It’s not right on the beach, either. Close, though.”

Erika tightened her fingers on the phone. Was he saying he wanted her to come?

“I don’t make a lot of money. I’m buying the house from my folks. They have a gallery, by the way. Actually they have three. I went into the one in Hanalei and looked for your prints. They have some.”

Parents. Did his parents live near him? The thought was reassuring. Mr. Family.

She asked, “What’s the name of their gallery?”

“The Okika. It means ‘orchid.’”

His voice was both warm and sandpaper rough. It made her want to hear him talk more.

But he was quiet.

Erika asked, “What does Hiialo do while you work?”

“Um…she goes to a day-care center.” Actually, she’d been to a few. One in a church basement with forty other kids. One with an elderly woman who had made the mistake of saying Hiialo needed a firm hand. The latest situation was a home with an unhappy dog tied up outside.

“My nephew used to be with me while I worked, when he was Hiialo’s age.” As soon as she’d said it, Erika wished she hadn’t. She sounded too eager. Desperate.

But an opportunity like this wouldn’t come again. Normal people wanted sex. Kal and his grief were her only hope.

“Hiialo is…” His voice startled her. “Well, she’s moody. In fact, she can be a bugger sometimes.”

“All kids can.” The dock made its endless aching cries.

“I’d like to…” On the lanai, Hiialo was making Pincushion and her stuffed lion, Purr, shake hands. Kal remembered proposing to Maka. At Waimea Beach. Kissing. I love you…“You could come over here,” he said. “I’ll buy your ticket. If it doesn’t work out, I’ll buy you a ticket home, too.”

“I’ll buy my own ticket.” Somehow. Her hand was deep in her hair, tearing at it. She felt like crying. What if he didn’t like her? What if he didn’t think she’d be a good stepmother for Hiialo? What if…“When do you want me to come?”

“Not right away. I have to figure out some things. About the house.” About how to tell his parents.

How to tell Hiialo.

“I’ll call you again, yeah?” he said. “And I’ll send pictures of the house. Maybe you could come in June?”

“That sounds great. I’m boat-sitting for my brother’s business partner. He’ll be back in June.” Oh, she sounded flaky. Practically homeless.

“Good,” said Kal.

Her worries evaporated. She was wanted—by a stranger. Why was he doing this?

He said, “Let’s get off the phone for now. I’ll call you again soon. Do you have any questions before we hang up?”

“Yes.” With a presence of mind that astonished her, she asked, “What’s your phone number?”

Moments later she set the receiver back in its cradle. Still sitting weakly on the steps, she leaned against the side of the counter and wept.

“DADDY, PINCUSHION’S stuffing is falling out.” As Kal hung up the phone, Hiialo appeared before him, bringing everything into immediate and demanding focus.

“You beat the stuffing out of him. That’s why it’s falling out.”

Hiialo started to look tearful, and Kal reached for Pincushion, who was made from a faded gray-blue sock and wore a turban. In addition to a split seam on the side, one of his felt eyes was coming off. Repair time.

“I’ll fix him.” Sewing up Pincushion would calm him.

A picture bride. Danny’s analogy was accurate, and since the night he’d said it, Kal had stumbled upon two accounts of Japanese picture brides from the turn of the century. One was in the newspaper, the other in a book sold in the office of Na Pali Sea Adventures. And he’d remembered that his parents’ next-door neighbor, June Akana, who had taught Japanese bon dances to him and his sister and brothers when they were kids, had been a picture bride, too. She and her husband were in their nineties, still going strong. Best friends. People could be happy.

But the picture brides of old hadn’t come to Hawaii for celibate marriage.

Oh, shit, what were his friends going to say? They all knew what he’d advertised for. He’d told them why, because of Hiialo, because he was never home and she needed someone who could be. He needed someone who would be. He killed a useless yearning. Not for love—for life. His own.

The Stratocaster in his hands. Playing…

But he was doing this for Hiialo.

“You’ll be all right, Pincushion,” said Hiialo, patting the toy in Kal’s hand. She trailed after him as he went to the kitchen drawer where he kept needles, thread, extra guitar picks, junk. The scissors were missing, as usual.

“Hiialo, I need your scissors. Could you please get them for me?”

“Yes, Daddy. Thank you for fixing Pincushion.” She went over to the couch and looked underneath it, then went to her room to find the scissors.

Sunshine. Hiialo was like sunshine now, but she was changeable as the north-shore weather. And sometimes as wild.

Would Erika Blade, a thirty-six-year-old childless woman, really be able to handle it?

Dear Erika,

I’m glad you’re coming to Hawaii. I’ll try to call you once a week. Here are the pictures I promised you of my house. You can see what Hiialo looks like now. She is holding Pincushion, who is her favorite toy…

I mentioned my family on the phone. My folks live in Haena, and my sister, Niau, lives in Poipu, on the south side of the island. My brother Leo…

MIDAFTERNOON sunlight shone through the open hatch and the windows of the Lien Hua. Lying in her berth, Erika read Kal’s second letter and studied the photographs he’d sent. At four, Hiialo was sturdy, with thick, wavy, medium brown hair cut in a pageboy. Even in the photograph, in which she was crouched on the lanai of the green bungalow with the thing called Pincushion, she seemed full of energy, ready to leap to her feet and race away. Not like Chris…

That’s okay, thought Erika. I know I can love her.

If she was certain of anything, it was her ability to love and care for children. Chris had been exceptionally good, exceptionally bright. Exceptionally quiet. But she could love Hiialo. It would be easy.

Another photo showed Kal with his brothers and sister and parents and their three dogs, all Akitas. His father—King, said the corresponding name on the back of the photo—was tall and white-haired. His mother, Mary Helen, seemed compact and athletic. And Kal and his siblings all had a look of radiant good health and of energy and power—not unlike the dogs. One brother was bearded, the other clean-shaven. His sister had shoulder-length light brown hair. They were a handsome family. Kal was the youngest.

The photo and letter, the proof that he really was a family man in every sense, reassured Erika. Since his phone call, she’d had doubts. Kal was a stranger. With David so far away, no one would really know if she got into trouble.

She ought to write to him, tell him.

She ought to tell someone what she was doing.

But she knew what her brother would say: Kal will get over Maka’s death.

For the hundredth time, Erika tried to quiet her qualms about that. She had advised him to wait—for someone else, someone he could love.

She should send him photos of her and David and Chris and Jean to give him the same kind of reassurance he’d given her. But she had no photos of herself with them, only with Chris, when she was in a wheelchair.

Not an option.

She looked back to the letter.

…I haven’t told anyone our plans. June is a long way off. Before you come, I’ll explain to my folks and Hiialo. Also, my in-laws. Maka’s folks live on Molokai, but her brother and her cousin live in Hanalei and they’re like family. In Hawaii, ohana, or family, means more than just your immediate relatives. It can extend to all your loved ones—

The telephone rang, and she went down into the galley to answer. It was Adele, calling to ask how the painting was going. Did she have anything else yet? Had she tried placing those “other pieces” in a gallery?

“Ah…I’m just experimenting right now.” Erika thought it through at light speed. “Actually a friend has invited me to Hawaii in June. I’m going to do some work there.”

“Oh, great! Which island?”

“Kauai.” Belatedly Erika recalled that Adele had seen Kal’s ad. But surely it wouldn’t occur to her that Erika had answered the ad.

It didn’t. “Wonderful. I think it’s recovered a lot since Iniki. The hurricane in ‘92? Try to get up to the north shore…”

Erika listened to Adele’s suggestions and chewed on her bottom lip.

Yes, it was good that David was in Greenland and no one really had to know what she was doing. She would write to her brother and tell him who she was staying with and where. But why say more? If it turned out that Kal didn’t like her, no one would have to know the truth.

“Erika? Are you there?”

“Oh, yes, I’m sorry. I’m spaced out today, Adele. What is it?”

“There are some galleries on Kauai that carry your prints. I’ll send you their names. I know they’d love it if you stopped in.”

The Okika Gallery, Erika remembered. Kal’s parents owned three galleries. It seemed like destiny. She longed to tell Adele everything. But if she did, Adele would worry. Anyone would worry, would question her judgment. Erika hated that. Better to say nothing, just leave Adele her new address and stick to her story. “All right.”

After they’d hung up, Erika climbed back up to the main cabin, where the paintings of Kal and Hiialo and Maka confronted her. She needed someone to ease her anxiety, to believe with her in this risk she was taking, believe that it would work out.

There was really only one person who could help with that, and Erika wished the phone would ring again.

He had promised to call.

Apelila: April

Dear Kal,

Thanks for your letter and the photographs and your phone calls. I painted the enclosed picture for Hiialo. I did it using the photos you sent. I hope she can recognize who it’s supposed to be…

The watercolor was of Pincushion. Kal loved it, had wanted to keep it himself. He’d considered taking it down to the gallery to get it framed, but then…Questions. How come he had an Erika Blade original. Of Pincushion.

I stole it, Mom.

Instead, he’d put the watercolor in a cheap document frame, replacing a photo of the great blues guitarist Robert Johnson, and he’d given it to Hiialo, as Erika had wanted, saying it was from a pen pal. After explaining what a pen pal was, he’d added, “Sometimes I talk to her on the phone, too.”

Soon he’d have to explain more. To everyone. Erika was coming to live in his house, maybe for good.

Sitting on the porch swing while Hiialo played in her room, Kal remembered his phone conversation with Erika just that morning. He had asked if she’d told her brother what they were doing. “I wrote to him,” she’d said, and Kal had wondered if she knew she wasn’t answering the question. He was pretty sure she did.

He was pretty sure she’d told her brother almost nothing.

Kal talked to her once a week, always calling Thursday at seven in the morning. It was his day off, Hiialo usually wasn’t up by then, and it was around ten in Santa Barbara. Making the call was agonizing every time. The cultural gap between them was bigger than Waimea Canyon. But Kal wanted to know all he could about Erika Blade before she arrived, before he brought her into Hiialo’s life.

She was hard to know. She turned conversations away from herself and tuned into him, perceiving his difficulties as a single father almost as though she’d been one herself. Or had known one, which she had.

Her brother.

He left the swing and went inside. It was already one o’clock, and he had things to do. He’d recently enclosed the back lanai, creating a new room—for Erika. It still needed finishing touches. But Danny and Jakka had stopped by that morning, and a jam session had eaten half the day. “Hiialo, let’s go to Hanalei. I need something from the hardware store.”

Kal heard a rustling from his room and took a step down the hallway, pushed aside the beads in his doorway and looked in. Hiialo peered up from where she crouched beside his open desk drawer, photos spread out around her. The portrait of a naughty girl.

Kal saw a photograph of Maka under the leg of his folding metal desk chair. Entering the room, he picked up the chair. The surface of the photo was marred, across Maka’s face.

“What are you doing, Hiialo? Those aren’t yours.”

She began a cry he knew would rise to a full-throated wail. She looked at a photograph in her hands, a snapshot of her mother, and ripped it in half.

“Hiialo.” Kal scooped her up, and she hit him with her fists and kicked him, screaming. “Don’t hit. I don’t hit you.”

Her small arms and legs struck a few more times, to prove that she didn’t care what he said, before she subsided to screams. He carried her through the beads and out into the main room and then through the curtain door of her room. Her voice had reached a high continuous sob, and she cried, “It’s your day off! You’re supposed to spend it with me! You’re supposed to spend Thursday with me!”

Kal couldn’t speak. Even as he left her on her bed, kicking the wall and crying, he wondered what he’d done that had made her that way.

Not enough time at home.

He should have skipped the music, told Danny and Jakka it was his day with Hiialo.

Listening to her shrieking, he wondered if all parents felt trapped. Guilty for wanting their own time. For wanting…

Music spun inside him, trying to soothe. “Rock Me on the Water…”

He went back into his room and saw the photos scattered on the floor, including the one that had been ripped in half. In the next room, Hiialo’s cries reached a crescendo, and Kal crouched down to pick up all the Makas from the throw rug.

HIS FATHER CAME BY late that afternoon to look at some bad siding on his rental property, the blue oriental house in front of the bungalow. Kal was caretaker of the vacation home. He cut the grass and cared for the plants and cleaned after tenants left. The blue house had been rebuilt after Iniki; he’d just discovered that the siding was poorly installed.

Leading Raiden, one of the Akitas, up to the porch, King asked Kal, “Where’s the keiki?”

“Taking a nap.” They stood together under the porch awning with the rain pounding the roof and the garden, and at last Kal said, “Yeah, it’s been a great day.” He told his father about the photos.

King shook his head. He’d seen Hiialo in a temper, too. They all accepted her moods as part of her nature, but everyone hated the sulks and the screaming.

Together the two men toured the back-porch room, scrutinizing the construction. King had never asked the reason for the project; the house was small. When they’d examined the new room, Kal offered him some juice—he seldom bought beer, which he liked but which made him sick—and they sat on the veranda with Raiden exploring the yard nearby.

The Akita had a pure white coat and double-curled tail, and Kal studied the dog with admiration and envy. His parents’ stud was immaculately bred, intensively trained, utterly trustworthy. Kal knew the time that went into raising an animal like that.

He didn’t even have time for his daughter.

Watching Raiden lift his leg against the heliconia, Kal said, “I’ve made friends with an artist in Santa Barbara. Erika Blade. We write letters. Talk on the phone.”

His father tipped back his cup of guava juice. “She’s a big artist. How’d you meet her?”

“I placed a personal ad. She’s coming to Kauai this summer. She’s going to stay here.”

Lazily King stretched out his legs and rocked the porch swing. “With you?”

On the top porch step, Kal shrugged. “Here.” His house, not his bed.

The rain drizzled, creating waterfall sounds all around the lanai, and Raiden came over to lie at his master’s feet.

“Is this romance?”

No, thought Kal. It’s practical. “Something like that.”

The rain poured from the gutter and splattered on the ground at the corner of the house. As Kal stared out at it, his father said at last, “Well, we’ll look forward to meeting her.” He stood up and so did Raiden. “I’m going to take a look at that siding.”

Kal glanced toward his own house. All was quiet indoors, Hurricane Hiialo sleeping. Watching the Akita follow his father down the steps into the rain, he drew a quiet breath. King hadn’t criticized, hadn’t shown any disapproval at all. Kal knew that when his father had said they’d look forward to meeting Erika, he meant it.

His parents always kept things in perspective. They’d survived Hurricanes Iwa and Iniki.

And Kal had cried in his dad’s arms after Maka died.