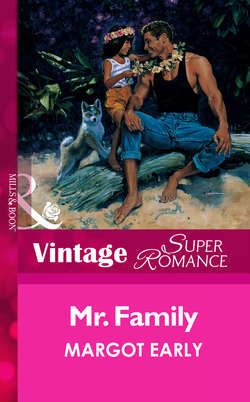

Читать книгу Mr. Family - Margot Early, Margot Early - Страница 8

CHAPTER ONE

ОглавлениеSanta Barbara, California

January

WANTED: Woman to enter celibate marriage and be stepmother to four-year-old girl. Send child-rearing philosophies to Mr. Ohana, Box J, Haena, Kauai, HI.

“THAT’S THE WRONG page.” Impatiently Adele reached over the butter plate with a long-nailed hand that seemed dwarfed by rings, onyx and jade in hand-crafted gold settings. She gestured for Erika to turn the magazine pages. “It’s in the middle.”

“Wait, wait. Look at this.” Strangely excited—in the same way she became excited when a painting was going well—Erika Blade handed Adele the copy of Island Voice, open to the ad for a celibate marriage. In the last few months she had begun to pay attention to personal ads, to flyers for computer dating services, to bulletins for singles’-club activities. She never acted on any of them. Only desperate people did things like that, and she wasn’t really even looking for a mate. Not exactly. She was simply…curious.

Celibate marriage. Send child-rearing philosophies…

If she was ever to answer a personal ad, this would be the one.

Erika and Adele sat at an ocean-view table in the Surf Room, the grand glass-enclosed breakfast room of the famed Montecito Palms Resort Hotel. The glass-topped table was graced with potted violets, fine bone china, heavy English silver, the remains of breakfast, and transparencies of several of Erika’s latest watercolors of women by the sea. Momoy Publishing, owned by Adele and her husband Kurt, had published many of Erika’s paintings as limited-edition prints. In fact, Adele had brought the copy of Island Voice because she’d purchased an ad in it for Erika’s recent serigraphs. Her work sold well in Hawaiian galleries.

But Erika was less interested in the prints Adele had already published than in her verdict on the work shown in the transparencies. Nervous, she’d flipped past her publisher’s advertisement, lost her place and stumbled upon the personal from Mr. Ohana.

As Adele squinted at the ad, Erika took stock of the changes in her publisher’s appearance. Though Adele was only five foot three and tipped the scales at 140, she’d never let that turn her from the world of haute couture—an attitude Erika admired. She loved color, and Adele was an ever-changing palette. Her hair was cut in a severe bob that slanted from ear level on the left to chin level on the right. Its present hue was eggplant—Cobalt Violet, Payne’s Gray and just a touch of Cadmium Orange, if Erika had wanted to mix it from paint—and her dangling purple-and-sapphire earrings matched. During their eight-year professional relationship, Erika had come to anticipate meetings with Adele as a time to vicariously enjoy nail polish, chic hairstyles and makeup.

And at fifty-one, fifteen years older than Erika, Adele was one of the very few people in the world with whom Erika felt comfortable exposing something of who she really was. Adele was her judge, support and promoter of the thing most intimate to her—her art.

“Tell me you’re kidding,” Adele said. “Not the personals, Erika.”

Erika suddenly realized that she’d been injudiciously enthusiastic about the ad. Even Adele would think she was crazy.

“God, is it the biological clock?” exclaimed her publisher. “If it is, I’ve got a fifteen-year-old son you can have.”

Erika laughed, glancing nervously out the window at the sun-soaked Santa Barbara Channel and the islands beyond. Because it was Adele, she said, “Oh, I don’t know. Having a kid underfoot doesn’t sound half-bad.” After this too-truthful admission, she rushed on, “I’m trying to picture this Mr. Ohana.”

“Well, I doubt it’s his real name. Ohana is the Hawaiian word for family. Actually it implies extended family,” explained Adele, whose second passion, after art, was Hawaiiana. “A feeling of helping one another, of loyalty.”

Erika leaned over the table to stare at the upside-down personal ad. “Mr. Family?” The pseudonym seemed tinged with self-mockery.

“Yeah. He’s got a real sense of humor. ‘Send child-rearing philosophies’?” Adele rolled her eyes, then gave Erika a dubious look plain as words. Celibate? Surely it’s not that bad. Rather than dwelling on her artist’s unnatural whims, she flipped through the magazine until she came to the advertisement for Erika’s prints.

Erika took the magazine again and smiled at the ad for Sand Castles. “Can I take this?” Erika held Adele’s copy of Island Voice questioningly above the straw carryall slung over the back of her chair.

“Sure. I brought it for you.”

Erika slipped the magazine into her bag and met Adele’s black-rimmed eyes.

Her publisher sighed. She gathered the transparencies, glanced at one of them under the light and put them in their envelope to return to Erika.

Erika’s heart fell. But somehow she’d already known Adele wouldn’t take a chance on them.

“Erika, these paintings just don’t have your usual vigor—or depth. And they’re very similar to things you’ve done before.”

It was true. “Is it because I used Jean for a model in several of them? She’s so gorgeous…” Her sister-in-law had posed for some of Erika’s best work, including Sand Castles. “I’m having trouble making people look real.”

“Well, in Sand Castles you certainly managed it.”

Sand Castles was a watercolor of Jean with Erika’s eight-year-old nephew, Christian. Erika knew her feelings for Chris had translated in paint. She had perceived and understood Jean’s nurturing of her stepson. Because, of course, she’d played that role herself. It was Erika’s best piece ever. But in her publisher’s candid response, she saw the truth—that it was rare for her to capture so much feeling in her art.

She counted on that honesty from Adele, who went on, “No, I don’t think Jean’s the problem. I think you’re afraid to take risks, and you’re trying to stay on familiar ground.”

The words tolled inside Erika like the bell of truth. Afraid to take risks…Erika had her reaction, which was emotional. Visceral. It was hard to get up after a fall. Adele had watched; she should know.

“Look,” said Adele. “I don’t want you to feel bad about this. I know what you’ve been going through this past year. A lot of change. I think Sand Castles is going to sell very well, and if it does maybe we’ll do a second series. In the meantime, you can work on some new projects.” Scraping back her chair from the table, Adele drew an enameled cigarette case and matching lighter from her handbag.

Erika frowned. With soaring cholesterol and bloodpressure, her friend was a walking time bomb. “You know, I want to have you around for a few years, Adele.”

“Trust me. I’m prolonging my life—using techniques from the Adele Henry school of stress reduction.”

Cigarettes, cognac and French cuisine…

Adele changed the subject. “Speaking of Jean, did you say you’re without her as a model for a while?”

Erika took the hint; she couldn’t force Adele to take care of herself. “They’re in Greenland. Studying walruses.” Erika’s father, Christopher Blade, had been a renowned undersea explorer, and her brother, David, had followed in his footsteps after his death. Now, David and his second wife, Jean, and his son were in the Arctic for a year. The expedition had followed closely on the heels of an overfishing study in Japan. In fact, they’d spent little time in Santa Barbara since David had married Jean a year before. The sea was their home. It had always been Erika’s, too.

Adele contemplated the burning end of her cigarette. “Kurt and I are leaving for Hilo next week. Why don’t you join us? Make it a painting trip?”

Erika smiled, shaking her head. She loved Hawaii; when she was nineteen, she’d spent three months there with her parents and David studying sharks. But she wouldn’t intrude on her publisher’s vacation time with her husband in their getaway on the Big Island. It occurred to her that Adele felt sorry for her. That was the last thing she wanted—from anyone. “Don’t worry.” She laughed. “I don’t plan to answer any personal ads while you’re gone.” Afraid to take risks. She’d just confirmed it.

Adele drew on her cigarette with a wry smile. “Hawaii can be tough on malihinis—newcomers. Especially haoles like us.”

Caucasians. Erika remembered the word.

“But, hey,” said Adele, “Haena’s a beautiful place. And all he wants is to know if you follow Dr. Spock or James Dobson.” She rolled her eyes again. “Take my advice. Get a dog.”

Erika’s present living situation didn’t allow for a dog. In fact, she’d never lived anywhere she could have one. Dogs were for people with homes. They implied permanence. Erika wanted permanence—if she could get it without more change. She’d known too much of that.

She contemplated the personal ad in Island Voice. Celibate marriage. She was probably one of the few people in the world who could see the appeal of that.

Mr. Family, she thought. Mr. Family.

Minutes later Adele paid the check with her gold card, and they stepped outside into a crisp winter breeze that made the palms chatter. Her faded carryall slung over her shoulder, her silk dress from Pier 1 Imports swishing against her legs, Erika accompanied Adele to her black Saab.

Erika walked with the slight limp that had become natural to her. Two years of rehab had made her strong and lean, but her legs would never be as they once were. She felt Adele’s appraising glance.

“You look great,” said Adele. “Really.”

“Thanks.” Adele had known her in the periods Erika thought of as Before, During and After. The present was After.

Something to remember, to be thankful for.

They paused beside the driver’s door of the Saab and embraced. “Now take care,” Adele told her, “and remember, the invitation to Hilo is open. Kurt would love to have you, too.”

“Thank you, Adele.” Erika released her. “Drive safely.”

After Adele had backed the Saab out of its space and driven off, headed for an appointment with an artist in Solvang, Erika made her way under the palms to her own car, the sun-bleached, sea-foam green Karmann Ghia she had bought eleven months before, when she began driving again.

Sliding behind the wheel, she set her carryall on the passenger seat. The copy of Island Voice showed from the top, and Erika drew out the magazine, thumbing through, looking for the ad for Sand Castles, to convince herself that she really could paint.

But she couldn’t find the right page, and instead, she turned to the classifieds in the back. Mr. Ohana…

Haena’s a beautiful place. And all he wants is to know if you follow Dr. Spock or James Dobson.

Nothing else.

Not even sex.

Erika shut the magazine and started her car. Afraid to take risks.

No pain, no gain; no guts, no glory?

No risk…no fulfillment.

Ever since David had met Jean, ever since Erika had begun to feel superfluous to her brother and his son, she’d been lonely. She missed Chris.

She wanted a family of her own.

But the usual route to that place was not for her. She always met the same obstacle in the road. No, really, it’s not you. It’s me. I’m just not ready for this. Trying to sound normal, blaming it on her accident.

Yes, Adele, I’m afraid. You would be, too.

Mr. Ohana’s personal ad, however…maybe this was a risk she could take. A child. A celibate marriage. Yes, she liked the idea.

But why did he want it?

What’s wrong with you, Mr. Ohana? she wondered. What’s your story?

Pepeluali: February

Haena: the heat

On the island of Kauai…THE RAIN SHATTERED through the Java plum trees and the ironwoods, drumming on the roof of the bungalow hidden in the foliage. Wet tropical blossoms gave off a heady aroma scarcely noticed by the occupants of the house. On the porch, Hiialo was catching rainfall in a plastic cup to measure—a “science experiment,” she had told Kalahiki.

Kal was glad she was busy—and happy. Everyone knew when she wasn’t. He turned from the envelopes littering the throw rug to the open front door and the barefoot little girl beyond. He could hear her voice under the rain, talking to a lizard out on the porch.

“Aloha, Mr. Skink. My name is Hiialo. This is Eduardo…”

Eduardo was an imaginary friend of Hiialo’s, a thirty-foot mo’o, or magical black lizard. A fearsome sight for Mr. Skink, thought Kal.

“Oh, don’t run away,” said Hiialo. “Eduardo won’t hurt you. He only eats shave ice.”

Danny’s voice drew Kal’s eyes toward the floor where he sat. “Spark dis.” Pidgin for “Check this out.”

Running a negligent hand through his short-cropped hair, Kal moved to stand over the muscular brown shoulders of his Hawaiian brother-in-law. On the floor in front of Danny lay a photo of a bottled blonde whose curves belonged on a beer poster. She stood beside a sailboard, smiling brightly at the camera.

Well, sort of brightly. Kal was choosy about smiles. A smile wasn’t a matter of orthodontic work or a pretty mouth. A smile came from the soul and shone through the whole being. A good smile was contagious.

There was a sound from Kal’s bedroom, the amplifier going on. Jakka, Danny’s cousin, six foot four and 240 pounds, emerged from the hallway, carrying Kal’s Fender Stratocaster guitar. He played a riff, and Kal’s own fingers itched for the strings. They’d planned to practice today.

Besides being part of his ohana, Danny and Jakka were members of his old band, the three-man band they’d called Kal Nui—high tide. And his former band mates haunted Kal’s house as though waiting for something to change, for that tide to come back in. But today’s jam session had never gotten off the ground. Danny, the percussionist, had seen Kal’s mail and wanted to read the replies to his ad. Now he was perusing the letter from the blonde with the sailboard. He grimaced. “She’s from the mainland.”

Jakka, whose fingers were master of the bass, slowly attempted the lead-guitar melody to “Pau Hana,” the song that had helped make Kal Nui the favorite band on the Garden Island. Long time ago…

Playing the right chords at the right tempo in his mind; Kal tried to lose the nervousness that had been with him ever since he’d visited his post-office box that day. Seeing the letters filling the box—and the larger stack he’d had to stand in line at the counter to collect—had made it real. He hadn’t been serious when he sent the ad to Island Voice. He wasn’t that desperate. It had been Danny’s idea. Nonetheless, Kal had written the ad. It had seemed barely possible to him that somehow it would all work out. He might find someone he could get along with, someone who would love Hiialo. Hiialo would have two parents again, instead of just a never-there father—him.

And he…well, maybe things would be better for him, as well.

He hadn’t expected many answers. At most, two or three. But now he was getting replies from not just Hawaii but the mainland. There were dozens of envelopes on the floor.

Danny pored over another letter. “Did you really say a celibate marriage?”

“Yes.”

Jakka stopped playing and frowned at the letters on the floor. “Nobody wants that.” A line divided his brow from top to bottom.

Kal said nothing. His stomach hurt. Work tomorrow. On your left is Kauai’s stunning Na Pali Coast. “Pali” means cliff, and…He reached into his shirt pocket and surreptitiously popped an antacid.

“You know,” remarked Jakka, “if you marry some rich woman, you could quit baby-sitting tourists and play with us again.”

Danny said, “That’s the whole idea.”

“No, it’s not,” said Kal, with a fighting-dog state no one challenged.

Maybe someday he’d play professionally again, but that hadn’t been the point of the ad. Hiialo was.

Smiling, bemused, Jakka toyed with the guitar strings again.

Kal wandered to the front door. Hiialo had filled two cups with rainwater and was busily filling a third. Her hair, a sun-lightened shade of brown that seemed the consummate mingling of his own genes with her mother’s, swung lank around her face and bare shoulders as she moved about the porch, wearing only a pair of boy’s surfing trunks.

She was just four, so Kal didn’t mind her playing at being a boy, going without a shirt as he often did. Still, it nagged at him. He shouldn’t be her role model. He wouldn’t be, if only…

Scarcely aware of the leaden pall on his heart, the dead feeling, he turned back to the room. To the letters on the floor. It wasn’t going to work. No way could he invite a stranger into his life or his home—or within a thousand miles of his daughter.

Danny tossed his wavy shoulder-length hair back from his face and sat up straight as he read the message inside one note card. “Hey, Kal. This one’s not so bad.”

Kal stepped over the stack of opened letters and crouched beside Danny, who handed him the card.

Danny glanced at his watch and began to stand. “Gotta work, brah. Good luck finding your picture bride.”

Picture bride. At the turn of the century, most immigrant plantation workers in Hawaii were poor single men. A man who wished to find a mate from his own culture had one option—to choose a woman from a photograph sent by family members or a marriage broker in his homeland. Then the picture bride came to Hawaii…

Kal groaned as Danny used his shoulder for support to push himself to his feet, feigning aching bones. Danny was on his way to meet his hula group. Besides playing drums, he was a dancer, like—

“Hey, wait for me!” Jakka unplugged the Stratocaster, then hurried back to Kal’s room.

Danny swept up his car keys. Nabbing Hiialo as she came inside, he swooped her up in his arms. “Gotcha. And Eduardo’s not stopping me.” Danny was always willing to enter Hiialo’s make-believe world, to accept the existence of her imaginary giant lizard friend.

As Hiialo squealed in delight, presaging her uncle’s turning her upside down, Kal examined the card Danny had handed him. On the front was a watercolor of a woman with long curly gold hair swimming underwater with a dolphin. Ordinarily Kal didn’t care for sentimental artwork—and he’d been around enough art to form an opinion. But something about this image struck him as realistic, natural, as though the woman and dolphin were actually swimming together. He studied the watercolor for a moment before he opened the card and read the writing inside.

The script was small and lightly etched, the letters running almost straight up and down.

Dear Mr. Ohana,

As Kurt Vonnegut says, “There’s only one rule that I know of—” It applies to child rearing as to anything.

“Damn it, you’ve got to be kind.”

Sincerely,

Ms. Aloha

“So what do you think?”

Kal hadn’t known Danny was paying attention. Even now, he was swinging Hiialo back to an upright position, his eyes on his niece.

Kal stuffed the card back into its envelope—another mainland address—tossed it on the stack with the rest and stood up. Taking Hiialo from Danny and feeling the comfort of her small slender arms circling his neck, Kal told his brother-in-law, “I think this was a stupid idea.”

“What was stupid?” asked Hiialo. Then, seeing Jakka emerge from the hallway, she said, “What was that song you were playing, Jakka?”

Danny burst out laughing, and Jakka approached Hiialo, threatening to tickle. “You didn’t like my song?”

Hiialo grinned, and Jakka ruffled her hair affectionately. He met Kal’s eyes, his own apologizing for his earlier remark. “I miss our band.”

Kal thought, I miss her. He’d lost all his music in one bad night.

“Laydahs, yeah?” Jakka squeezed Kal’s shoulder briefly, then wandered out onto the lanai, down the steps and into the rain.

As Jakka crossed the tiny lawn to stand beside the zebra-striped door of his cousin’s lavender-and-green VW bus, Danny lingered on the porch. “You got to be kind,” he mused. Swiftly he executed a ka hola, four bent-legged steps to one side and back to the other, his hands and muscular arms saying aloha. “I like Ms. Aloha.” With a last tug on Hiialo’s hair, he turned and leapt down off the porch and into the rain.

“Danny!” In Kal’s arms, Hiialo perfectly and gracefully imitated her uncle’s aloha, eliciting approving laughter from Danny and Jakka. Stirring useless pangs in Kal’s heart.

Wish you could see her, Maka…

As his friends climbed into the Volkswagen and the bus backed out and disappeared down the wet driveway, Hiialo pulled the sleeve of Kal’s T-shirt. “Can we go to the gas station and get shave ice? Eduardo’s hungry.”

“That mo’o is going to eat up my last dollar on shave ice.”

“Please?” Hiialo smiled at him from her eyes, from ear to ear, from her heart. “And can we stop and see Grandma and Grandpa at the gallery? I have a picture for them.”

Her grin made him grin, too. So much like someone else’s smile…Kal asked, “You know who has the best smile on this whole island?”

Hiialo kissed him. “My daddy.” She slid down, starting for her bedroom, knowing they would go get shave ice.

“Put on a shirt,” he called after her.

“I know,” she said, as though he were so tiresome. “I have to dress like a girl.”

DAMN IT, YOU’VE GOT to be kind.

Kal turned again on his mattress, trying to quiet his mind—and ease the burning in his gut. But the moon outside was too bright, and tonight he couldn’t make his breath match the rhythm of the waves hitting the shore just two hundred yards away. He shifted his chest against the bottom sheet, wishing he could sleep. His fingers spread on the mattress, and he remembered touching something more.

But this bed, the captain’s bed he’d built of koa just to fit his small room, this bed was only wide enough for him and then some—Hiialo when she bounced up beside him with a book in the mornings, wanting him to read to her.

Hiialo…Shave ice…His eyes closed, and his mind, drifting off, played music. His own. Chords. Finger-picking…

He opened his eyes and stared without focus at a groove in the paneling beside his bed. Sitting up, Kal grabbed a pair of loose cotton drawstring shorts beside the bed and pulled them on.

He put his bare feet on the floor and reached past his two packed bookshelves, filled with humidity-warped paperbacks, music books, lives of musicians. His fingers grasped the neck of the Gibson L-50, familiar as the limb of a lover, and he pulled it from its hanger on the wall. As he slipped out of the room, he passed the other instrument still hanging, the shiny chrome National etched with palms and plumeria, and those in cases on the floor, the Stratocaster and the Les Paul. The guitars saved him each night. Companions in the emptiness of forever. Loyal as dogs.

In the dark, he went into the narrow front room and pushed aside the hanging curtain to look in on Hiialo. She slept in one of his puka T-shirts—full of holes. Her mouth was open, her legs uncovered. Kal drew the quilt back over her.

“Thank you, Daddy,” she murmured in her sleep.

“I love you, keiki.” She made no response, and Kal headed out onto the lanai through the open front door.

He inhaled the ocean and the flowers, the jasmine crawling up the wood rails, and as he sank down on the tired porch swing and stared at the plants in the moonlight, he felt the water hanging everywhere in the air.

A sprawling blue house with an oriental roof, a vacation rental owned by his parents, stood between the bungalow and the beach. No view from his place, but Kal could hear the ocean and the insects, the bugs of the wet season. He saw the gray shape of a gecko doing push-ups on the porch. Watching it, he reached for the unseen with his mind and his soul.

Nothing.

Where are you? he thought. I need you.

It was one of those nights.

She was dead.

He strummed his guitar, tuned up in the moonlight. A flat, F minor, B flat seven…“The Giant was sleeping by the highway/winds called pangs of love brewed on the sea…” The words were symbols of Kauai and of his life—with her and without her. “Why didn’t you wake up, Giant?/Why didn’t you wake up and save me?”

He sang into the night, the act of singing easing tension in his abdomen, and he didn’t hear the sound of feet. But he noticed the small body climbing up onto the swing beside him.

Fingers still, he stopped singing. “I’m sorry, Hiialo. Did I wake you?”

She shook her head, her lips closed tight, middle-of-thenight tears-for-no-reason nearby.

Kal rested the old archtop in the swing, the neck cradled in a scooped-out place in the arm. It was a system he often used—for holding a guitar so that he could hold Hiialo at the same time. He lifted her into his lap and cuddled her against him.

“I don’t like that song,” she said. “It’s sad.”

That was true. And the song was true. Mountains didn’t rise up to stop fate. Kal hadn’t been able to, either. Not the accident. Or Iniki, the hurricane.

It wasn’t a truth for children.

“Want to hear ‘Puff’?” Kal had played “Puff the Magic Dragon” too many times in bars in Hanalei to consider it anything but agonizing. Still, it was Hiialo’s favorite, and maybe Puff could wipe that teary sound out of her voice.

But Hiialo shook her head, snuggling closer against his chest.

Five seconds, and she’d say, Wait here, and dash off to get her blanket and a stuffed thing called Pincushion that Kal couldn’t remember where or when she’d gotten. Whenever she tried that trick, he’d get her back into bed, instead. If allowed, she would stay up all night.

Like him.

Hiialo whispered, “I wish you weren’t sad.”

Something shook in Kal’s chest. He opened his mouth to say, I’m not sad. But he never lied to her.

He hadn’t known he seemed sad.

“You make me happy, Hiialo. The best part of my day is seeing you after work and finding out what you’ve been doing.”

Hiialo’s little fingers touched the few dark golden hairs on his chest. “Will you tell me a story about my mommy?”

Kal winced.

“Tell me about when you were in the band in Waikiki and Mommy—”

“How about not?” He kept his voice light. “But I’ll play ‘Puff.’”

She shook her head. He took a breath and watched the trade winds make some nearby heliconia, silver under the full moon, wave back and forth like dancers. Maka had moved like that.

Gone.

In a weary tone of resignation, Hiialo said, “I’ll hear ‘Puff.’”

“What an enthusiastic audience we have tonight.” Kal set her on the swing beside him, then picked up his guitar. As he started to play and sing about the dragon, he thought, I’m not the only one who’s sad.

Hiialo couldn’t remember. But she felt the void.

Later, after he’d tucked her in with Pincushion and the invisible Eduardo, Kal went to get his guitar and hang it up in his room, and on the way he noticed the paper grocery bag into which he’d stuffed the letters to Mr. Ohana.

Damn it, you’ve got to be kind.

Yes, he thought. Be kind to my daughter.

He put away the Gibson, and then returned to the front room that was kitchen and dining room and living room crammed into a hundred square feet. He grabbed the grocery sack, took it to the boat-size chamber where he slept, turned on his reading light and dumped out the letters on his bed.

He had to push them into a heap to make a place to sit, and then he read them and dropped them, one by one, back into the paper bag on the floor. He’d work up a form reply to the letters. Thank you for responding to my ad in Island Voice…Good luck in life and love. Sincerely, Mr. Ohana.

Only one note he laid aside, without taking the card from the envelope. He could cut out the picture of the girl and the dolphin and give it to Hiialo to tack on the wall of her room.

Damn it, you’ve got to be kind.

Finally he took an old spiral notebook and a pen from his desk drawer, and he lay on his bed and wrote a letter he didn’t intend to send to a woman he’d never met. The bag of letters on the floor seemed pathetic—answers from a sad but hopeful world to an even more pitiable plea. But their collective refusal to despair gave him a fleeting, moonlight-made hope. And after he signed the letter, “Sincerely, Kalahiki Johnson,” he got up and pulled open another drawer, the big bottom drawer, and drew out the shoe box full of photos.

Pushing aside the cassette case that lay on top, cached among things he loved, he flipped through the snapshots, careful of fingerprints. Careful of his own eyes. Pictures still hurt.

The photo Christmas card showing the three of them was near the top. It seemed right. Stealthily, not wanting to wake Hiialo, not wanting his actions to be known in the light of day, he went out to the kitchen to find scissors and finally picked up Hiialo’s green-handled little-kid scissors from the floor by the couch. Biting closed his lips, his eyes blurring in the ghostly gray dark, he cut apart the photo.

Maka’s arm still showed, stretched across his waist as she touched Hiialo, and for a moment Kal pondered how to remove it. But at last he left it, because then Ms. Aloha would understand what he’d tried to say with words.