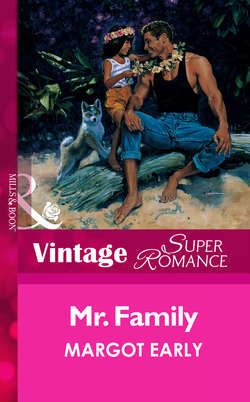

Читать книгу Mr. Family - Margot Early, Margot Early - Страница 9

CHAPTER TWO

ОглавлениеSanta Barbara

ERIKA COMMITTED HERSELF to overcoming fear of risk. In the days after she answered Mr. Ohana’s ad, she photographed scenes on the streets of Santa Barbara. A pink poodle outside Neiman-Marcus. Children giving away kittens in front of the supermarket. She spent as much time petting the poor dyed dog as photographing it, and she wanted to adopt a kitten. Instead, she developed the pictures and painted from them, telling herself this was the kind of gamble she’d promised to take. These were not women by the sea.

But what would Adele say? Would she say that Erika might lose her following? If her art stopped selling, if she had to get another job, she would die. Flower without water. Painting was all she had.

Erika’s reaction to the possibility was detachment; she tried to feel equally aloof about the other risk she’d taken. Answering a personal ad.

So when she pulled bills and catalogs out of her post-office box and saw a number 10 envelope hand-addressed to Ms. Aloha, she muted her feelings. The response had come from K. Johnson, Box J, Haena, Kauai.

K. Johnson.

Mr. Ohana.

She didn’t open the letter in the post office or when she reached the Karmann Ghia parked at the curb. Instead, she set her mail in the seat beside her and drove down State Street toward the harbor. She parked in the marina lot, in Jake Donahue’s space. Jake was her brother’s business partner and sometimes first mate on his ship. Jake was going to be in Greenland with David until June, and Erika was boat-sitting his Chinese junk, the Lien Hua. It was a usual sort of living arrangement for her.

Temporary.

Erika collected the mail and her shoulder bag and crossed the boardwalk, pausing at a gate in the twenty-foot chain link fence outside Marina C. She used Jake’s key card to open the lock and made her way down the creaking dock. Erika was painfully familiar with the harbor. It was where she had lived with her brother and his son on David’s old ship, the Skye. It was where she had lived During.

That was over, she reminded herself again. This was After.

Memories of that earlier time would always be with her. Some things shouldn’t be forgotten. Some things couldn’t be.

She reached the Lien Hua’s berth. Walking alongside the junk to its stern, she caught her muted grayish reflection in the dingy glass windows. Tall. Rayon import dress. Hair that fell several inches below her shoulders, neither smooth nor curly, brown nor blond, but simply nondescript.

Erika unlocked the cabin of the junk and ducked through the hatch, descending into the two-room space that contained all her worldly goods and most of Jake Donahue’s. Her art supplies lay on the fold-out kitchenette table. Unfinished watercolors covered the meager wall space in places where the sunlight wouldn’t fade them.

She tossed her mail on the narrow bunk where she slept. K. Johnson’s letter was on top, but Erika resisted picking it up, tearing it open. Restraint was possible through routine.

She opened the overhead hatch, then dropped down a companionway to the unlit galley. In the gloom, the light on Jake’s answering machine glowed steadily. No messages. From the small icebox run on dockside electricity, she took a bottle of fresh carrot juice. Erika removed the lid and sipped at it.

Suddenly she could wait no longer. She capped the juice, put it back in the refrigerator and returned to the salon and her mail.

She took K. Johnson’s letter topside, where the air smelled of beach tar, and settled in a wooden deck chair in the shade of the mast. The closest sailboats were deserted, covered. Opening the letter, Erika was glad of the solitude, glad her brother was faraway across a continent and an ocean, glad Adele was across another, glad no one could know that she’d done this insane thing. That she, a thirty-six-year-old woman, had answered a personal ad involving a celibate marriage.

And a four-year-old girl.

As she withdrew the letter and unfolded it, something dropped into her lap. A photo, upside down. Erika didn’t look. She put her hand against it, protecting it from the breeze, and turned to the page. The letter was written in black ballpoint pen on warped paper torn from a spiral notebook. Neat male handwriting.

Dear Ms. Aloha,

My name is Kalahiki Johnson, though you know me as Mr. Ohana, who placed a personal ad in Island Voice. I am thirty years old, and I was born and raised on the island of Kauai, where my father’s family has lived for six generations and where I work as a tour guide on the Na Pali Coast.

My four-year-old daughter is named Hiialo, pronounced Hee-AH-lo, which means “a beloved child borne in the arms.” Soon Hiialo will be too big to carry, but she will always be the most precious thing in my life.

Hiialo’s mother was my wife, Maka. Maka was a hula dancer and chanter who won competitions in hula kahiko, traditional hula, and also in hula auana, modern hula, both of which tell stories. She was a kind and graceful human being in every way, and we loved each other deeply. Three years ago, driving back from a hotel where she’d been dancing, she was killed in a head-on collision.

Erika set down the letter, biting her lip, unable to read on.

She’d thought that he was some yogi who’d taken a vow of abstinence. Or maybe that he was impotent or burned out on relationships. She’d wondered about Mr. Ohana’s reasons for wanting a celibate marriage, but she hadn’t expected anything like this. Though she should have.

Why was it affecting her this way? And she was affected, her eyes hot and blurry, her heart racing with horror, as though she’d just learned of the death of someone she loved.

And he was only thirty.

Since then I have raised Hiialo alone, but I work long hours, and it’s hard on her. I wish there was someone who could do what Maka would have done for our daughter and who would love Hiialo as she did.

If you are still interested in Hiialo and me, please write back. But understand that even if a permanent domestic arrangement is possible, your relationship with me would be platonic. Maka and I were married for seven years, and no one can replace her in my heart. I want no other lover, and I would prefer to live alone, if not for Hiialo. Please understand this, because, as you said, we all need to be kind.

Sincerely,

Kalahiki Johnson

Erika put the heel of her hand against her mouth, pressed her lips together. In her mind, she heard an echo of the past, and she couldn’t shut it out. One word repeated itself.

David.

Her brother.

For the three years after his first wife’s death, Erika had lived with him. For three years, she had been a mother figure to his son, Christian. That had been the best experience of her life, though it had begun out of duty. There had been much entangled pain—David’s and her own, both caused by the same woman.

But this situation was different. So different.

Talk about risk.

The winter breeze pushed at her hair, and Erika reached for the photo in her lap, so that it wouldn’t blow away. She turned it over, and her breath caught when she saw him.

He was a beautiful man.

Light brown hair, still damp from a swim, stood out in short uncombed spikes, as though he’d just come out of the water and shaken it. His lean muscular chest and arms were tanned the color of oak. The child’s skin, the skin of the almost-toddler in his arms, was a shade darker. And darker yet was the rounded well-toned female arm brushing his body, the hand touching the baby.

Maka. He’d cropped her from the shot, all but her arm.

Erika absorbed every detail of the picture. The sea. The man’s smile. His grin came from sensuous lips and slitted dark-lashed eyes of uncertain color and, clearly, from his heart. Anyone could see he held the baby often. Erika saw gentleness and love between the child in her green swimsuit and the man who held her in front of him, feet out to face the camera. Somehow the baby had been coaxed into a dimply laugh, and Erika wondered if her father’s fingers cupped under one small bare foot were responsible.

The picture was like a book, and when she read it she cried.

Erika heard the dock creak and saw a couple who owned a sloop two berths down approaching. Not wanting to talk, she stood up and limped to the cabin door, slipped inside. The junk rocked gently. She listened to the lapping of water, to some wind chimes outside. The monotonous music of solitude.

Her heart felt simultaneously fearful and excited.

He had answered her letter. From however many replies he’d received, Kalahiki Johnson had chosen hers. His answer had contained no proposal of marriage, no promises. Just an invitation to write back.

She lay down on her bunk and read it again.

Twice.

Three times.

The light faded outside, and she turned on the lamp over the bunk and studied the photograph and the letter, memorizing the words, especially the last paragraph.

A sensible part of her, the part that was the older sister of a man who’d lost his wife, wanted to step back and say, “Oh, Kalahiki, you’re young. You’ll fall in love again.”

But the photograph won a debate words would have lost. And Erika resisted admitting even to herself that he did not seem a man destined to live out his life in celibacy.

I have to tell him.

She would have to tell him about herself. Reveal her past to a stranger and hazard rejection because of it. It would be unconscionable not to tell him, but the prospect was horrible.

Erika found comfort where she could.

I don’t have to tell him everything.

Haena, Kauai

KAL PEDALED HARD through the rain to the post office to collect his mail. The transmission on his car had given out, so that morning he’d cycled to the office of Na Pali Sea Adventures in Hanalei in the rain. He would get home the same way, in the dark, on one-lane roads and bridges, veering into the brush and mud when headlights approached. Raindrops clattered against the wide green leaves all around him as he pulled up outside the small building of the Haena post office. It was after five, so the counter was closed, but Kal could still go inside and open box J.

“Please, Mr. Postman…” He thought in music all his waking hours. He dreamed music in his sleep.

Rain dripped from him onto the stack of bills and flyers he drew from the box. The letter from Santa Barbara was on top. The return address sticker read “Erika Blade” and had a logo of an artist’s palette beside it. Alone in the office, he tossed the rest of his mail on a bench, sat down and opened the envelope, his curiosity stronger than his embarrassment over the letter he should never have mailed.

To Ms. Aloha.

Erika Blade.

She had sent another card. Same artist, different picture. A very old woman sitting in the sand, gazing out to sea. The ocean really looked like the ocean.

As Kal opened the card, the photo dropped out faceup.

A good-looking brunette in cutoffs and a faded T-shirt sat against the side of a weathered wooden building with a drawing board against her knees and a paintbrush in her hand. She had long muscular legs and a laughing smile.

A good smile.

But sunglasses hid her eyes.

Reflexively fishing for an antacid from a bottle in his pack, Kal studied every detail, down to the shape of her toes, before he turned to her small delicate handwriting, which covered the whole inside of the card and continued on the back. She had a lot to say, and as he chewed on a tablet, he read with curiosity, not with hope.

Dear Kalahiki,

Thank you for answering my note. Reading of your terrible loss made my heart ache. I am so sorry about your wife’s death, and I wish there were something I could do to ease your grief.

My conscience dictates that I precede this whole reply with the advice that you not marry anyone at this time. Despite the things you said in your letter, I believe there is more love in store for you. You should find it before marrying again—for your daughter’s sake and your own.

This is what I believe, but I can’t know your heart. Leaving your choices to you, I’ll introduce myself.

My name is Erika Blade. I am thirty-six years old and a watercolor artist. But probably, if my last name is familiar, it’s because my father was the undersea explorer Christopher Blade. My brother, David, and I grew up on his ship, the Siren, and accompanied him and my mother all over the world on scientific expeditions until I entered art school in Australia and began to make art my career. While I was at school, the Siren sank and my parents were killed. My brother continued my father’s work, and I have helped him some.

About five years ago, I was seriously injured in an automobile accident. Though luckier than your Maka, I was temporarily paralyzed.

During the three years I spent in a wheelchair, I lived on my brother’s ship with him and his son, Christian. Chris was three at the time of my accident; he lost his mother soon afterward. For three years, I helped my brother look after him, and this experience shaped who I am today. I love children.

Eventually I decided to move off David’s ship and into a place of my own. Shortly afterward, I regained feeling in my legs. With the help of therapy, I have been walking for about eighteen months, but because of knee injuries in the accident I still walk with a limp.

Because my parents are dead, my family consists of my brother, his wife, Jean, and my nephew, Chris. However, they are seldom in Santa Barbara anymore; David’s work takes them all over the world. In any case, I want a family of my own. And, like you, I prefer celibacy. The arrangement you have suggested appeals to me very much. I think it would be good for me. I’m less sure it would be best for you and your daughter.

So, Kalahiki, I leave you to your thoughts. I would always be glad to hear from you again.

In friendship,

Erika Blade

The last line was her phone number.

On the front of the card, Kal found her name. No wonder she could paint the sea. Christopher Blade’s daughter.

Did his parents have her prints in their gallery?

Erika…

When he’d placed the ad, it was with the hope that there was someone like her out there. Someone who wasn’t interested in sex—but who still seemed capable of a meaningful relationship. Someone who loved children and would love Hiialo.

But Erika Blade didn’t know Hiialo. And he didn’t know Erika.

Can’t do this.

Kal replaced the photo and the card in the envelope, put them in his day pack with the other mail and stood up. Pushing open the glass door of the post office, he went out into the rain and the scent of wetness and grabbed his ancient three-speed Indian Scout from where he’d leaned it against the siding.

The downpour pelting him, Kal flicked on the headlight on the handlebars and pedaled out to the road, his T-shirt and shorts immediately drenched anew. He crossed a long stone bridge, riding as though he could escape the rain, and his heart raced. His mind replayed the contents of the letter, and he knew he would read it again that night when Hiialo was in bed.

Christopher Blade’s daughter. Three years in a wheelchair.

He could hear his tires on the wet pavement and the sound of the violent winter surf just a block away, a sound that once would have called him to the breaks at Hanalei Point, to Waikoko or Hideaways. Freedom…

Don’t even think about bringing her here, Kal. You never really planned to do it. It just seemed better than having your daughter in day care.

To temper tantrums and moodiness.

To trying to do it alone.

To messing up.

But he couldn’t go through with this. It wouldn’t be right.

Why not? Riding through the rain, Kal tried to remember exactly what Erika Blade had said about sex. Hardly anything.

Painful thoughts came.

Loneliness.

The glow of headlights cast a long shadow of his body and bicycle ahead of him on the water-running pavement. Kal steered into a roadside ditch, springing off his bike when the front wheel stuck in the mud. As rain streamed down his face, a red 1996 Land Rover whipped past. Kal recognized the vehicle. It belonged to a movie star who used his fifth home, in Haena, two weekends of every year.

Reminding himself to buy a helmet, Kal yanked his bike out of the mud and back to the road before he realized the front wheel wouldn’t turn and the forks were bent. He stood in the rain, and it drowned his voice as he yelled after the long-vanished car, “I hate your guts, malihini! You killed my wife!” He knew it wasn’t really the driver of this car who’d hit Maka—just someone like him. Someone who would never belong.

Kal leaned his arms on the handlebars, his head in his hands.

Erika Blade would be a malihini, a newcomer, too.

He wouldn’t write to her again. He’d said personal things to her. She’d said personal things to him. They were even.

And her advice was sane. Wait for love.

Wait…

He’d waited three years, dated women. They’d made him miss Maka even more.

Kal picked up his bike, slung it over his shoulder and began walking home through the rain. There was nothing to wait for.

She would never come back.

THE OKIKA GALLERY in Hanalei was a renovated plantation-style house with white porch posts and verandas. Next door, separated from the gallery by a wide walk bordered with heliconia, anthurium, spider lilies and ginger, a similar building housed the office of Na Pali Sea Adventures, the outfitter for whom Kal worked. The two buildings shared a courtyard away from the street.

The morning after he received Erika’s letter, there were no Zodiac trips going out, so Kal’s job was to shuttle sea kayaks to the Hanalei River for the tourists who had rented them. At ten-thirty, when he returned from that errand, he slipped out for his break.

It was raining, but the espresso stand in the courtyard was still doing business as he dashed through the downpour to the steps of the gallery. He entered through the open French doors, and Jin, his mother’s champion Akita bitch, stood up and came over to greet him.

“Hi, Jin. Hi, girl.” Kal crouched to pet the dog’s thick red-and-white coat, to rub her back and behind her ears, to look into her eyes in the black-masked face. As Jin licked his cheek, Mary Helen, his mother, abandoned a mat-cutting project at the counter to join him.

Kal had gotten his height from his father. With her neat tennis-player’s body and no-nonsense short blond hair, Mary Helen stood barely five foot two. She always looked at home in shorts, polo shirts and slippers—elsewhere known as thongs—the footwear of the islands. Born and raised in Kansas City, Missouri, Mary Helen had first visited Oahu in 1960 and met King Johnson at a dog show, where their Akitas had fallen in love and played matchmakers like something out of One Hundred and One Dalmatians. Or so Kal had been told. His mother had left the Midwest and moved to Hawaii to marry King. Gamely she’d faced the challenges of island life, slowly exploring her new world, learning the social subtleties and embracing the cultural richness of Hawaii. Hawaiian quilting, Japanese bon dancing, foods as unfamiliar as poi and kim chee—Mary Helen loved them all. When she and King had children, they had given them Hawaiian names. Now, in the critical eyes of the locals, Kal’s mother was considered a kamaaina, a child of the land.

Could Erika Blade do that?

“Hi, sweetheart,” said Mary Helen. “No trips today?”

“No. I’m going to go get Hiialo in a minute.” When Kal had no trips to guide, his boss, Kroner, let Hiialo work with him at the Sea Adventures office, doing small tasks her four-year-old hands could manage. Despite her tantrums, Hiialo had a knack for winning friends.

“She can come over here,” his mother said. “I’ll be here all day. I’m changing some prints on the wall.”

Kal had come to look at prints, but his taking a sudden interest in the family obsession—art—would make his mother suspicious. “I’ll bring her over to say hi. I’m going to clean the equipment room next door, so I thought she could help.” His parents gave enough to Hiialo; she spent every Tuesday with them at the gallery.

“Oh, that’s good for her.” His mother smiled approvingly. “And she’ll have fun.”

Kal straightened up from petting Jin, who walked away to keep watch out the front door. Why had he placed that ad, anyhow? It wasn’t as though Hiialo had no female influence in her life. She had his mother and his sister, Niau.

“Your dad took Kumi to the vet,” his mother told him. “And Niau went to Honolulu. She took Leo some prints. Did you know he’s remodeling? He wanted you to help.”

“I know. He called me.”

Kal’s oldest brother—Lay-oh, not Lee-oh—ran a gallery on Oahu. Keale, the next oldest, was a park ranger on the Big Island. Uncles and aunts. What didn’t Hiialo have? If he wanted, they could even get a dog, one of his folks’ Akita puppies. Though he wasn’t home enough…

He wasn’t home enough.

He needed a partner.

Kal sensed his mother looking him over, and he knew she was wondering if he’d wind up in the hospital again, receiving a blood transfusion. Apparently deciding he was going to make it, she smiled and said, “Come tell me what you think of this oil painting. A man from Kapaa painted it, and I think he’s good.”

Where usually he would have begged off, Kal followed her to the counter, surreptitiously scanning the walls. He didn’t need to look that far. When he reached the counter, he saw that one of the prints his mother was putting up or taking down was by Erika Blade.

He tried not to stare, but he recognized the model as the same woman in the dolphin card Erika had sent. In this print, the woman was building a sand castle with a boy.

It was the best of her work he’d seen. The interaction between the woman and child, their absorption in their construction project, conveyed a lot. Motherhood. Happiness. Friendship. Nurturing. Fun.

If Erika Blade had a lot of prints out, she was probably doing well. What Jakka had said weeks before needled him. Marry a rich woman.

Not a pretty notion, but practical. Kal wasn’t looking for a woman to support him so he could play professionally again. But he worked six days a week. Needed to. At least she can support herself.

He dutifully assessed the oil landscape by the Kapaa artist. “It’s nice.” But his eyes drifted back to the print.

Jin left the door, wandered over to them and sat down by the counter. The Akita looked at Kal and so did his mother.

“Isn’t that lovely?” Mary Helen asked, noticing his interest in Erika’s print.

“Yes.” Kal turned away, chewing on unasked questions.

“That’s hers, too, up there,” said his mother. “The girl sailing. We sell a lot of her work actually. Her name is Erika Blade. I think she’s disabled.”

“Oh.”

Mary Helen’s head was tilted sideways, as though she was listening for the akua, the island spirits, to give up secrets. She was staring curiously at Kal, picking up on the anomaly of his looking twice at a piece of art.

“Well, I’m going to get Hiialo,” he said. “I’ll see you later.”

Then he left, before the akua could tell their tales.