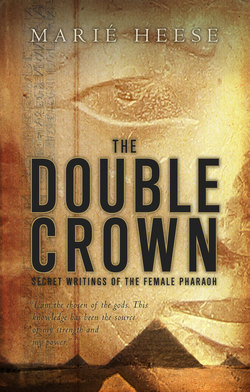

Читать книгу The Double Crown - Marié Heese - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

THE THIRD SCROLL

ОглавлениеThe reign of Hatshepsut year 20:

The first month of Peret day 12

I now continue with my task of setting out the proofs that I am the chosen of the gods. I loved hearing the tales of Hathor who had suckled me and Hapi who had cradled me. But the one I loved best was the story of Apophis, who had spared me from a certain early death. Apophis, the serpent god who lives in the nether regions of the world and is the enemy of men and gods, terrified Inet so greatly that she disliked even saying his name. As a child who was assured of safety, I greatly enjoyed the sense of danger that the tale gave me. “Tell me about Apophis,” I would beg her.

“Speak not of him,” said Inet, clutching at an amulet that always hung about her neck to stave off evil spirits.

“But he is on my side,” I said. “Otherwise I would be dead. Unless, of course,” and I glanced up at her sidelong through my lashes, “you have always lied to me about it.”

“Sitre, Great Royal Nurse, does not lie,” she said, her small black eyes narrowing to furious slits. She was own cousin to Hapuseneb and so of noble descent, although she had not been educated as he was. Sometimes she could be quite imperious.

“So tell me. It was two years after I sailed in the coracle, wasn’t it?”

“One,” said Inet, reluctantly. “You had four summers. In fact, it was the middle of the fourth summer of your life. The midday meal was over and everyone was resting in the heat of the day. It was extremely hot. Even your brothers were resting in their rooms.”

“It was here, in this very palace, wasn’t it?”

“In this very palace, right here, in hundred-gated Thebes. You and I were on this self-same portico with the stone pillars that looks out across the flower gardens.”

“I could hear the fountains splashing and the doves murmuring in the palms. I remember that.”

“I was resting on a wooden day-bed with cushions stuffed with wool,” went on Inet, “and a slave had been keeping me cool with an ostrich-feather fan. You lay on the floor on a thin cotton rug because the tiles were cool, and soon you fell asleep.”

“So did you,” I said. Another reason why Inet hated to tell this tale.

“Just for a minute,” she said, defensively. “It was so hot. And it was so quiet. Even the cicadas seemed to have gone to sleep.”

“And the slave went away,” I said.

“To fetch some cooled fruit juice, so he claimed. Since we would be thirsty when we awoke. And indeed, I did awaken. I am sure I had only just dropped off. But I sensed a presence,” said Inet, warming to the drama of her story. “An evil presence. An imminent danger. I looked around, but I could see no human being. And then I looked down at where you were sleeping. And in the shadows, on the edge of the portico, close, oh so close to your little sleeping head, with your child’s lock of hair falling across your face, cheeks rosy with the heat …” Inet clutched her amulet and made a sign to ward off the evil eye, her voice falling to a whisper … “there he was.”

“Apophis,” I said, shuddering deliciously.

Inet gulped and nodded. “Apophis,” she confirmed. The serpent god. The narrow-hooded cobra, who attempts to ambush Ra when he sails through the nether regions of the world in his solar barque.

“Swaying from side to side,” I added.

“Five cubits of dark evil, coiled up,” said Inet dramatically. I think that the snake grew in length with each telling of the tale, but no matter. “I was petrified,” said Inet. “I was truly turned to stone, like a statue hewn from granite with my feet planted in rock. I could not move. I could not utter.”

“And I slept,” I said.

“Praise be to the gods, you slept. The evil one swayed and his tongue flickered and he looked at me. I knew I looked at death. Nothing moved. And there was no sound. It was as if I had gone deaf as well as dumb.”

“I did not move either.”

“No, you did not move. Just breathed a little faster than usual because of the heat. And then Apophis lowered his head. And he slid forwards.” Her voice dropped even further. “Right across your body. Clear across your chest. I swear it. But you did not move. And then he slipped over the edge of the portico and he disappeared into the shadows of the apple trees and he was gone.”

“And the slave returned with the juice,” I said.

“He did. And then I screamed and he dropped the pitcher, which shattered on the tiles, and I rushed forward and picked you up and hugged and kissed you and you were frightened by my anguish, so you cried, and …”

“It was general mayhem,” I said. I liked that phrase.

“It was. But soon we all calmed down and the floor was mopped and we drank some juice.”

“Apophis spared me for my destiny,” I said with satisfaction.

This event finally confirmed Inet in her belief that I was the chosen of the gods. Suckled by Hathor, cradled by Hapi, and spared by Apophis: How could I not have a high destiny? It must, she devoutly believed, be so. Of course, when I was a little girl and my brothers the princes were still alive, it was not clear exactly what the gods had called me to do. Perhaps, suggested Inet, I might become the God’s Wife of Amen, a position of great influence and power. She did not whisper the supreme title of Pharaoh in my ear. Yet within a few years of the visitation by Apophis, the Crown Prince was dead. Well I remember the day.

There was consternation in the palace. Just after midday, when as a rule the rooms were silent, with only the splash of water from the courtyards and the occasional soft footfall of a barefoot slave to be heard, there were suddenly voices exclaiming, people rushing about and weeping and wailing.

“What is it, Inet?” I demanded to know. “What has happened? Has war broken out?” I rather wished it had, for it seemed to my youthful imagination that it would be very exciting.

“No,” said Inet grimly. “I think not.” She vanished into the passage and reappeared soon after, shaking with shock.

“Inet! Inet, what has happened?” The palace women were now rending their clothes and tearing their hair. I had not seen this before and it was frightening.

“It is your brother Wadjmose,” she said, in a tone of disbelief. “He has gone to … to join the … the Fields of the Blessed.”

“Wadjmose is dead?” I was too young to understand that one did not use such terminology in Egypt.

“Hush. He will be with the gods,” she told me, but somehow she did not look delighted by the news.

“But just yesterday he was playing with his pet lion cub,” I said, stupidly. “He can’t be … he can’t have … gone anywhere.”

“It was a flux,” said Inet, wiping away tears with the back of her hand. “They say … they say his bowels turned to water, black water, and he … and he … he could not live. My child, you must come. The Queen your mother wishes to tell you herself.”

I was ushered into the chamber where my mother sat: the Great Royal Wife, clad only in a thin linen shift, her head that normally bore an intricate wig topped with a crown now shaven and bald, her face hard yet wet, as if hewn from basalt and naked to the rain. I looked at her and I turned and fled. This could not be. I could not bear it. I ran from the palace as if Seth and all his devils howled at my heels and I headed straight for the river bank. Such confusion reigned that nobody stopped me, at least not until I had almost reached my goal. Then a hand shot out to grab my arm.

I blinked away my tears. It was Thutmose, my half-brother, borne to my father the Pharaoh by the Lady Mutnofert, a minor wife; he was walking up from the river with a fishing pole on his shoulder. I knew him from the palace school, where I had just begun to learn, painstakingly, to write a clean hieratic script, and he was among the seniors, since he was eight years older than me.

“Little sister,” he said, “where do you rush to so heedlessly?”

“T-to the river,” I stuttered, hiccupping. “Wadjmose has died of a flux, and everyone has gone mad and Mother … and Mother …” I could not find words to convey the horror of my regal, self-contained and always beautifully groomed mother stripped to the bone by grief.

“Wadjmose has … gone to the gods?” He was astounded. “You are sure of this?”

I gulped, and nodded. “It was a f-flux,” I whispered, wiping my running nose on my bare arm.

He handed me a linen kerchief. “Indeed,” he said. “And you are going to the river to … ?”

“To talk to Hapi,” I told him. “I often do.”

He nodded as if this made sense to him, put his arm around my shoulders and began to walk with me. “They will not seek me for some time,” he said, “nor you, I think. Let us go and sit upon the bank.”

So we went down to the river’s edge, and we stared at the water surging by; it was at the time of the first rising and the Nile was green, promising a good inundation and rich harvests to come. I wept on my brother’s shoulder and his hands were gentle as he stroked my hair. The humid air was scented with damp earth and rotting leaves. I could not tell him that it was not so much my brother’s passing for which I wept, but for my broken mother with her naked suffering skull. My world was rent. Mothers did not weep. Divine royalty did not weep. I wanted somebody to tell me that the thing that had happened was not so.

He held me till I finally became calm.

“How do you talk to Hapi?” he enquired.

I peered at him from between my clotted eyelashes. Was he laughing at me?

“Is it necessary to speak aloud?” He appeared to be truly interested.

“No,” I said. “You can just … you can just … think.”

“Then let us think together.”

We were quiet for a while.

“And does Hapi ever answer you?” he asked at length.

“Sometimes … sometimes it seems to me … that an answer comes,” I said. “Sometimes she sings to me.”

“And today?”

I tilted my head, listening. Today there was nothing but the wash of the water through the reeds and a croaking frog.

“Nothing,” I said, forlornly.

“Your question, no doubt, was why?”

Of course he was right. I nodded.

“And you hear nothing.”

I agreed wordlessly.

“Not quite nothing,” he pointed out. “I hear the water. And the water is rising. What has that meant, little sister, for many thousands of years?”

“It has brought life,” I said. “Hapi brings life.” For every year the great river swells and floods its banks, so that the entire land looks like an enormous, turgid brown lake in which villages sit like islands and the trees seem half their size; this annual inundation deposits rich black earth all along the banks of the great river. Then when it recedes men can plant new crops, so that seeds may germinate under the sun, and harvests sprout and mature and be brought in.

I still did not understand why our brother had had to go to the gods, but the images conjured by the rushing water comforted me. Thutmose’s understanding presence comforted me. In truth, before he was my husband and the Pharaoh, he was my friend. I put my hand in my brother’s hand and struggled to my feet. “They will be looking for us,” I said.

“Yes. We must return. But, little sister …”

“Yes?”

“You have a personal slave? One who can taste your food?”

“Yes.”

“Eat nothing that has not been tasted,” he warned me.

“But I … but I am only a child,” I said.

“A child who bears the blood royal,” he reminded me.

“And there is still Amenmose,” I argued, “and … and you.”

“But there are power-hungry men in Egypt who would love nothing better than to rule over the land. We do not know for sure – do we? – why Wadjmose died. Should the Pharaoh – the gods forbid it – pass into the Afterlife soon, all of his children might need to have a care.” His dark eyes were very serious.

“I see,” I said in a small voice. I had seen no more than seven risings of the Nile that day, yet it was the end of innocence for me.

I mourned my brother the Crown Prince. But I began to entertain a secret dream. I dared to dream of greatness.

It was the songs of the blind bard, coupled with Inet’s tales, that gave form and direction to my dream.

He came to the harem palace when I had seen nine risings of the Nile. It was the first time that I was allowed to attend a formal banquet where the King my father presided, instead of being sent to the children’s dining room with the rest of the palace children.

I wore a simple white linen shift and a little string of blue glass beads, but Inet had refused to let me line my eyes with black kohl and paint the lids with green malachite. There would be time enough for that later, she said. Yet she had tied a wax perfume cone on top of my head just like the other ladies had and I felt very grown-up. During the course of the evening it melted gradually, keeping me cool and scented with myrrh.

It was hot and noisy in the dining hall. I was given a gilded, richly decorated chair to sit on, just like the rest of the adults and their guests, a deputation from Syria who had brought tribute and gifts and all manner of things to barter.

The dinner went on and on. Female servants kept bringing more dishes piled high with delicacies, piping hot from the kitchen, where (I knew because I loved to go there) the chief cook sweated and shouted and swore and threw things at his minions. At the tables, though, all was decorous. I enjoyed the tender veal and the freshly baked wheat cakes, dripping with honey, and I had a slice of sweet melon afterwards. Naturally the adults ate far more – joints of roast beef studded with garlic, fat roasted ducks stuffed with herbs, rich goose livers pounded to a paste, steamed green beans, lentils and carrots, fig puree, cheese and dates. And of course, plenty of wine that had been cooled in earthenware jars. How could people eat and drink so much, I wondered.

I remember all these things so clearly because it was the first time, but also and mainly because of the blind bard. He was a member of a group of musicians, most of whom were girls; they played on double pipes and lutes and shook tambourines; the smallest rhythmically thumped a drum and several were expert at clicking the menat. But the bard, whose bald head shone in the lamplight like polished cedarwood and whose eyes gleamed milky white like pearls, played on a small portable harp and his music could have charmed the dead out of their tombs.

His first song was merry to begin with, ending, however, on a plaintive note. His fingers on the strings were gnarled, but the sound was like water over rocks, like the wind in the trees.

“Weave chains of blooms to give to your beloved,

Rejoice, rejoice in the days of youth.

Be happy, breathe in sweet scents.

Keep your loved one ever near,

Do not stop the music,

Do not stop the dance,

Bid farewell to all care!

Pick delights like flowers in the fields.

For soon, too soon the time will come

When to that land of silence

You and your love will both be gone.”

The bearded Syrians in their gaudy robes were becoming very merry and did not take kindly to the sad, haunting quality of the last lines. “Give us a song of great deeds,” their leader shouted, banging on the table with his fist.

“Aye,” chorused his fellows, who had already looked deep into the wine jar. “A song of great deeds!”

The blind bard inclined his head, swept his knotted fingers deftly across the singing strings, and said, in his deep voice: “I sing The Song of the Godlike Ruler.”

The rowdy Syrians cheered. Soon the power of his music had charmed them into stillness, and they listened even as I did.

“Hearken to the Song of the Godlike Ruler.

His Majesty came forth as the Avenger.

For the enemies of Ma’at were many

And the Black Land suffered, aye it suffered much.

His Majesty came forth as the Destroyer.

He smote the adversaries of righteousness,

He washed in their blood,

He bathed in their gore.

He cut off their heads like ducks.”

This was far more to the taste of the Syrians, who cheered and then settled down again.

“His Majesty drove back the fiends of Seth.

He triumphed over all the foul fiends.

Aye, he was victorious over his foes.

He fixed his southern boundary-stone,

He fixed his northern one like heaven,

He governed unto the eastern deserts.”

Now the rest of the musicians joined in, in a swelling chorus.

“His Majesty came forth as Atum.

He crushed iniquity.

He repaired what he had found ruined.

He restored the boundaries of the towns.

He rebuilt the temples of the gods.

His Majesty restored Ma’at,

And all the people praised him.”

A trumpet sounded a clarion call above the singing strings and the flutes. Cymbals clashed.

“Aye, His Majesty was a godlike ruler.

He came forth as Atum.

He held the Black Land in his hands,

He held it safe.

He triumphed over evil.

He was a shining one clothed in power.

And all the people praised him.”

There were more songs that night and much carousing – and drunkenness, I have no doubt. But Inet came to take me away before things became too rowdy and I did not protest. I lay in my bed, on my sheets of fine linen over a mattress stuffed with lambswool, and I kept hearing the thrilling words of the blind bard:

“Aye, His Majesty was a godlike ruler.

He came forth as Atum.”

How wonderful, I thought, to be a godlike ruler. As indeed my father the great Pharaoh was. How wonderful to hold the Black Land in one’s hands. To hold it safe, to triumph over evil. And to be loved by all, and praised:

“He was a shining one clothed in power.

And all the people praised him.”

A shining one clothed in power. Oh yes, I thought. That was a destiny to desire. Not a tame existence in the harem. And although at that time my elder brother Amenmose was still alive, yet I felt in my bones that such a destiny would be mine.

Early the next morning I went out into the palace garden and encountered one of the Syrian deputation sitting on a bench in front of the fish pond, staring despondently into its depths. He must have been a young man, but to my eyes then he seemed quite old. He had a curly beard and curly locks and his brown eyes were bloodshot.

“Good morning,” I said.

He groaned. “A good morning it is not,” he responded. He spoke our tongue passably well and he had a pleasant voice, although it came thickly from his throat. “I looked too deeply into the wine jar and I am paying the price for it.”

“Why then are you up so early?” I enquired. “When my brother Amenmose has drunk too much, I think he sleeps until the afternoon.”

“I am not up early,” he said, “I am still up late. I mean, I have not been to sleep as yet. We caroused all night and then we began to gamble and I lost.” He rubbed his face blearily. “Somehow, someone seems to have stuffed a lambswool sock into my mouth,” he complained. “One that was not recently well washed.”

“Nor were you,” I said.

He looked affronted. “You are remarkably pert, for a child,” he said, regarding me with more attention. “Ah, the little princess.” He leaned back lazily. “The little princess with the golden eyes. If I give you a bracelet, as golden as your eyes, will you send it to me by messenger when you are come of age?”

“Why should I do that?”

“Because I think we might have more to say to each other in a few years’ time,” he said. The expression in his eyes was one that later I would learn to recognise, but at that time it was new to me. It disturbed me somewhat and yet I liked it.

“When I come of age, I shall be Pharaoh,” I said. I had not meant to speak my dream but it slipped out.

He laughed, then groaned and held his head. “Beware of what you desire, my dear,” he said. “You might achieve it. Besides, you have a brother, do you not?”

I dropped my eyes. Of course I did not wish my brother harm. “I am younger than he,” I muttered. “One does not know …”

“I shall send you the bracelet,” he promised, with a grin.

He did so later that day. He knew who I was but I did not know him; when the slave brought the bracelet, of beautifully chased gold, in a little cedarwood box, he told me that it was a gift from the prince. He was the youngest scion of the royal house of the Mitanni in Syria. I had not thought that a prince could smell so. Yet I had liked him and I kept the bracelet. I have it still.

Here endeth the third scroll.