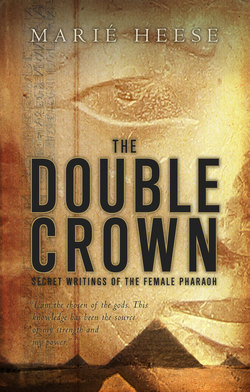

Читать книгу The Double Crown - Marié Heese - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

THE FOURTH SCROLL

ОглавлениеThe reign of Thutmose I year 15

When I was eleven, Inet’s prediction came true: I was called to serve my father as the God’s Wife of Amen. I was also Divine Adoratrice; this position can only be held by one who is unmarried and pure. I took enormous pride in my task. I had to be present during the daily temple rituals, so that I knew and understood them. I helped my father destroy by burning the names of Egypt’s enemies, a ritual that gave me great satisfaction. I led groups of priests to the temple pool to be purified. I learned the dances that kept the God in a state of arousal. Young though I was, I was assisting my father the Pharaoh, as he explained, to guarantee the eternally recurring recreation of the world through the life-giving powers of the God. And a thrilling experience it was for a girl child who otherwise might have been restricted to the palace schoolroom, or learning to spin flax.

I also accompanied my father on some of his trips around the Black Land, for my mother, the Queen Ahmose, may she live, had much to do in the harem and was at times not well. I remember the first official journey that my royal father and I made together. Up to that day I had never travelled very far from the harem palace where I grew up, and I was very excited. We would be sailing to Heliopolis, to visit the priests at the temples there, and I would have a role in the rites.

We were to travel by boat, but although it was an official journey it was not a royal progress and the way would not be lined with cheering crowds. The boat would not be the exquisitely decorated solar barque on which the Pharaoh sailed during the major festivals. It was a large, comfortable vessel, though, with a high bow and stern, and a dais packed with soft cushions and shaded from the harsh sun by a colourful canopy. Slaves stood to attention with fans to keep us cool, and of course the royal guard would attend on us. Several smaller boats bearing bureaucrats and servants sailed with us, and the kitchen boat, from which delectable aromas wafted across the water, was never far behind.

This was the first time I met Senenmut. He was the scribe chosen to accompany us. At that time, when I was eleven years of age, he was a young man of eighteen. He was deferential, as was only right, but he did not seem overawed at the company in which he found himself, for he had a natural dignity and carried himself with assurance.

I liked his looks at once; he was taller than most men, with broad shoulders and a strong nose. His dark eyes under thick brows regarded the world with a slightly amused expression. I tried to observe him indirectly, with sidelong glances, and I noted that he had elegant hands with long fingers that were not stained with ink as a scribe’s hands so often are. His hair was thick and dark and he wore it long; when the sun caught it, it had blue-black gleams. It looked as if it would be soft to the touch. I would like to run my hands through it, I thought.

He helped me onto the dais with a firm grip, and when I looked up to thank him, he actually winked at me. Well! A scribe with some audacity, I thought, feeling my cheeks grow warm. I lifted my chin and pretended to ignore him.

Once we had taken our seats in the shade, the King my father removed the crown of Lower Egypt that he had worn while being borne to the quay in his sedan chair, and which he would wear again when being met at Heliopolis. I saw that he had but little of his own hair left and the remaining tufts were grey. His dark eyes could still pierce one with a hawk-like glare, but the kohl he wore (as most adults do to help deflect the sharp rays of the sun) could not hide the surrounding folds and lines, and he looked – I must write this down, for I am bound to write the truth – like a leathery, tired ex-soldier with a stiff hip and a soft belly that overhung his studded belt. Clearly his teeth pained him, for he rubbed his jaw and sighed.

I was saddened by this view of my royal father. I knew that he had been a great general and a renowned warrior, about whose achievements on the battlefield many admiring tales were told. Always he had seemed to me to be a person of great stature and dignity, a person invested with authority and not a little mystery. But I took comfort from the reflection that his royal Ka would surely maintain its force even as his earthly body became diminished.

We would be sailing with the current, but against the wind, which almost always blows from the north. However, there was very little wind that morning, so the rowers would not have as hard a task as they would have done had the wind been strong. High on the bow a tall Nubian stood, keeping time for the rowers with a large brass gong; the rowers chanted a rhythmic song as they bent to their oars. As usual the river was busy. Other gongs from similar boats could be heard across the water. Shouts and orders echoed. Light boats woven of reeds slipped between the heavier barges carrying large cargoes of materials and food and the fine boats similar to ours that would be bearing persons of status.

We had set forth early but already the day was warm; the sky was a cloudless blue reflected in the water slipping by. My father was resting with his eyes shut; he seemed to have dropped off to sleep. For a moment I wondered whether he still breathed, but then a gentle snore reassured me. But I was far from sleep and I sat upright next to Senenmut the scribe, imitating his scribe’s pose with the folded knees. Ah yes, time was when I could sit like that for a long time and then jump up and run.

I was fascinated by the bustling river traffic. Between the smaller boats some large ships were ponderously navigating the waterway towards the quay that we had left, bringing, I knew, cedarwood from Lebanon, gold from the mines in Sinai, ivory, ebony, strange animals and more gold from Nubia.

“Look, Princess,” said Senenmut, “there go the Keftiu. They have sailed from very far away, where few Egyptians have ever sailed.” He looked envious, as if he too would like to sail to distant lands.

I decided to allow him back into my favour. “Would you like to do that?”

“Above all things,” he said, with a sigh.

“So why are you not a sailor?”

“My father thought a scribe would have better prospects.”

“I think our sailors should be more venturesome,” I said. “There may be rich lands that we know not of, with whom we could also trade our grain and wine, our linen and pottery. When I am Pharaoh …” I bit my lip. “If I were Pharaoh,” I amended, peeping at him from under my lids. He kept his face straight, but his eyes were twinkling. I had the feeling that very little would ever escape him.

“Yes, Princess?” he prompted politely.

“I would order our sailors to explore,” I said. “To go further than they are used to.”

He nodded. “You too would like to go further than you are used to, I think,” he said.

“Indeed I would,” I said. “Indeed I would.”

Just at that moment we were approaching a bay of striking beauty on the western bank, where stark, massive rock formations reared up behind a broad plain. A white building, not very big and partially fallen in, stood against the cliffs. Yet it had graceful lines, fronted by crumbling terraces linking with the plain.

“What place is that?” I asked sharply, jumping up from the dais and moving to the side of the boat. Senenmut rose to join me.

“The bay, Princess, is Djeser-Djeseru, a holy place where Hathor resides. The building is the temple of Mentuhotep the Second, may he live. He was a great Pharaoh, a unifier and a builder.”

“I like the sound of that,” I said. “A unifier and a builder. Good things to be.”

“Yes,” agreed Senenmut. “It is a mortuary temple, of course.”

“Of course,” I said. The temple of Amen-Ra at Karnak lay at our backs on the east bank and it was a living, working community. If I turned around I could see its impressive pylons and pillars. The west bank, I knew, was the abode of the dead; many mortuary temples stood there, with shrines where offerings were made to feed the Kas of Pharaohs who had gone to the gods. “It is a pity that the temple is in such a state.”

“Mentuhotep and his successors saw to it that Egypt prospered,” said Senenmut, “but Mentuhotep the Fourth was overthrown by his chief minister, Amenemhat. Maintaining the mortuary temples of the previous dynasty was not … ah … a priority.”

“He must have been a fool to allow his throne to be usurped,” I said scornfully. “Yet the temple could be restored. Or rather … something of greater … greater magnificence … could perhaps be built beside it.”

“Djeser-Djeseru calls for a structure that dominates the plain,” observed Senenmut, staring at the soaring, rugged cliffs that glittered in the early sunlight.

“I agree,” I said, excitedly. “That would be wonderful. It would be the most wonderful temple that the world has ever seen.”

He whistled faintly. “That would demand an extraordinary design, Princess.”

“Yes, it would. But it could be done.”

The bay was slipping past as our boat sailed on.

“It could be done,” agreed Senenmut. He stared at the site as if measuring it with his eyes. “In fact it should be done. One day.”

“One day,” I echoed, trying to hold the image of those magnificent cliffs as the shore sped by.

From that moment he held a special place in my life. I think that there are few things that so bind two people as a shared dream; especially if it be somewhat outrageous and a difficult one to realise.

Together we leaned on the railing, looking back as the boat left the magnificent bay behind. I was standing downwind and suddenly noted the masculine scent of the scribe at my side. Involuntarily I leaned closer, inhaling him. Oh, I do like this man, I thought. I like him so much. I would wish … I would wish to … to dance for him as I do for the god Amen-Ra. When I looked at him sidelong, he was smiling down at me as if he knew my thoughts. I could feel my cheeks flushing hotly.

Just then there was a slight lurch. We had had to avoid a funeral boat carrying a gilded mummy case on its deck that had cut across our prow. Then the rowers recovered their rhythm and we approached a bend in the river. The temples of the living and the dead were left behind. We returned to perch upon the dais again. A slave girl began to play on a lute and sing and we sat listening companionably. Her voice was like clear water running over stones. It seemed to me that it was the very voice of Hapi, the river god who had sung to me so often, singing in my heart; singing a song of limitless possibilities. I closed my eyes, thinking: This must be what it is like in the Fields of the Blessed.

Suddenly the voice of the royal guard who rode the bow of the boat shouted a warning: “Beware, hippo!”

We had just rounded a bend in the river and were passing a small bay with a gently sloping sandy shoreline fringed with palm trees and lush green pasture. In the background white hills shimmered in the lucent sunlight. I realised with a shock that what I had taken to be a cluster of boulders in the shallow water near the shore was in truth a huddle of hippos cooling themselves. There appeared to be a number of calves, little boulders resting close to the huge bulk of their mothers.

At this moment the kitchen boat – considerably smaller, of course, than the royal barge – passed us on the shore side. Doubtless the chefs wanted to get to the place where we would stop for lunch before us so that the tables could be set out. Then a peculiar sound filled the air, a sort of honking wheeze; several of the cows in the shallow water opened their cavernous mouths as if they were yawning.

“Look out!” exclaimed Senenmut. “Here comes trouble.”

I noticed that one of the hippos was moving towards the kitchen boat with a bobbing motion, almost a gallop, blowing explosively every time it sank below the water. The boat’s rowers had now seen it too and were attempting to pull away into deeper water, but the charging monster attacked at such a speed that they could not evade it. The vast jaws opened and closed on the stern of the boat with a crunch. A high-pitched scream rent the air. The boat tilted as water streamed in through the gash, spilling rowers and other slaves into the river.

Again the huge jaws yawned and snapped together. I stared in horrified fascination as a sundered leg floated past us, colouring the water pink. Some servants still clinging to the foundering boat belaboured the hippo with oars. It roared and chomped once more. The royal barge had swung around to come to the rescue and two of the royal guards had flung their spears at the attacking animal, but to no avail as they simply bounced off its hide.

My father, who a moment before had been nodding against the cushions, had leapt to the side of the barge. Now he clambered to the bow and grabbed a spear from the hand of the lookout. Balancing on bent knees as the barge swayed, he waited for the next angry lunge. Suddenly he was once more a powerful warrior. Tautly poised, he almost seemed to shine. Into the open throat of the furious hippo he hurled the spear, straight and true as if aiming at a murderous enemy upon the battlefield. It struck home. The hippo coughed gouts of blood, emitting thunderous, gargling bellows of pain and anguish. It thrashed around in the reddening water. But it would fight no more. Pharaoh had triumphed. He had come forth as the destroyer and the danger was past.

The survivors were taken aboard our barge and we sailed onward. The physician who had of late begun to travel with the Pharaoh assisted the wounded. Someone would take care of the wreckage and salvage what they could. The other hippos would probably not attack anyone, Senenmut told me; it seemed that the kitchen boat had come between a mother and her calf, which had been sucked into the middle of the river by the current, running strongly since it was the season of Akhet.

I no longer remember everything that happened on the rest of that journey. There have been so many journeys since. Yet I recall every word that Senenmut and I exchanged. I remember how much I liked his voice, deep and resonant. I wanted to see more of him, but at that time our paths did not often cross.

In the year that followed, the royal house was again plunged into mourning by the passing of the Crown Prince. My brother Amenmose, who was an expert hunter and a superb soldier, broke his neck falling out of his fast-racing chariot during an ostrich hunt. He was killed instantly.

They brought him to the harem palace amid fearful weeping and wailing and laid him down on the bed in the room that had been his before he went to the Kap to be trained as a soldier. As soon as I heard the ululations of grief, I knew that something momentous had occurred. I ran to the room that seemed to be the centre of the storm. There he lay, with nothing more out of the ordinary to be seen than a graze running down the side of his cheek. Otherwise he looked just as if he slept: a young, handsome man, with a pronounced nose like that of our father the Pharaoh, and powerful arms and legs thanks to his military training. He might have been resting quietly on a long march.

The Royal Physician came and confirmed that the prince had indeed gone to the gods. My mother sat by his side holding his cold hand, but this time she did not weep, although I could see that shudders shook her frame. My father walked the floor and raged at everyone who had gone along on the expedition. He needed someone to blame. Nobody noticed me.

This time I did not run to talk to Hapi. Instead, I walked to one of the courtyards and sat down next to a fish pond. In the water golden carp circled.

A shadow fell across the water. I looked up. “Oh, it’s you,” I said, recognising Senenmut. Sad as I was, my heart lifted at the sight of him.

“I have heard about your brother, Princess,” he said. “It is grievous news.”

“Yes.” We were both silent for a bit. “Sit down and talk to me.”

He folded his legs into his scribe’s pose. More silence.

I closed my eyes, picturing the moment of sudden flight that had ended my brother’s life. “A terrible shock,” I said. “A sad loss.”

“Are you?” he asked. His dark eyes were questioning.

“Am I what?”

“Are you sad? Truly?”

“Why should I not be?” I asked indignantly. “I have lost my brother!”

“Then why do you not weep?”

I glared at him.

“It brings you closer to the throne,” he reminded me. “If you would still be Pharaoh.”

I had, truth to tell, been trying not to think this, yet thinking exactly this, and feeling at the same time enormously guilty to be thinking it. But I did not like this scribe looking so clearly into my shameful heart. “How dare you!” I said furiously. “You presume much!”

“You have the full blood royal,” he observed. “It would be natural, to be thinking about the succession. You need not feel shame.”

“I am not ashamed!” I scrambled to my feet.

He tilted his head back, looking at me with eyes like slits. “Then do not be so angry. It suggests guilt.”

He had thrust me into confusion and I liked it not. But I did not know how to depart with dignity.

“They say …” He stopped, tantalisingly.

I took the bait and sat down again. “Well, what do they say?”

“They say that the axle may have been … tampered with. It seems that the chariot had lately come from a complete overhaul. It should have been sturdy.”

A chill ran down my back like a small, cold snake. “Who would have done such a thing?”

“Someone in whose interest it would be for there not to be a strong Pharaoh when the current one passes, may he live for ever.”

“Such as?”

“Such as the priests, perhaps? It would greatly increase their power and influence.”

I nodded. This made sense. I trailed my hand in the cool water. The fish rose, snapping, as if expecting food. I glanced at the scribe. His eyes were calculating, as if he was not sure what to think of me. He could not – surely! – imagine that I had known, had in any way been involved …

“I did not wish my brother harm,” I said. “Truly, I did not. He was years older than me and I did not see much of him before he went to the Kap, but I did not … I would never … I did not wish him harm. You must believe it.”

He nodded and stood up. “I was called to the office of the palace housekeeper,” he said, “but that was before all of this. Yet I should go and see …”

“Of course,” I said, shortly. “Go.” He should wait, I thought crossly, to be dismissed. I was a princess, after all. But to him I was a child.

I looked after the tall figure with the broad shoulders as he walked away. I was affronted that he had looked at me suspiciously. I wanted him to look at me differently. Like … like the priests looked at me when I danced as the God’s Wife. Like that.

With my brother lying dead, I should not have been thinking of such matters. But I have sworn to write the truth, and the truth is that I did think of him so. I did.

Here endeth the fourth scroll.

I knew the late great Senenmut, may he live for ever. Indeed, I knew him well, for I often worked with him as one of many junior assistant scribes on the numerous building projects that he directed for Her Majesty as Overseer of the Royal Building Works. I was included in listing different types of building materials because I was a quarry scribe for a time and I know materials, especially marble. I was often present when Her Majesty came to inspect a site or to confer with Senenmut on a particular statue or decoration that she desired.

He was, I think, the only one of her officials who ever dared to oppose her in any matter of considerable importance, but he actually did that on more than one occasion when I was present. Mostly they were in complete accord as to what should be done, but sometimes she had an idea that he did not accept. He would not agree to build anything impracticable, nor would he allow her to make changes that would affect the integrity of the completed work. At times I feared that she would send him to the quarries for impertinence, but in the end he always had his way. And instead of falling from favour, he seemed only ever to rise – at least until shortly before he went to the gods. Something must have happened then, for he came less often to the palace and their behaviour was coldly formal and stiff. Her Majesty began to call on me more often at that time. And then he was gone.

I have my own opinion as to why he got away with so much. I noted how his face blazed with joy when he saw the royal barge approach a building site where he was working on the river bank. She would lean on the side, looking out for him. They would look at each other with such intensity that … well, he might as well have thrown out a grappling hook. I saw how her gaze followed him as he moved about giving orders and checking completed work. There was great admiration in her face, but a sadness also. A kind of yearning look. And then she would compose herself, and shake her head, and attend to the various complaints.

There have always been rumours, of course, that Senenmut was more to her than an official. Others had also noted what I have written of. Those who were jealous of his swift rise and the many titles Her Majesty conferred on him spread such gossip maliciously.

But I do not believe it. No, no, I do not. For one thing, they could never have been alone. There are always many officials and servants and slaves about. For another, he was a commoner. Not only did he not have royal blood, he did not even come from a noble family. How could he aspire to be the lover of one who was a Pharaoh and divine? He, who came from a family of market gardeners, as Hapuseneb used to sneer. No, it was not possible. Besides, his abilities were so outstanding that they were reason enough for his remarkable career. Quite enough.

Senenmut was a legend among the younger scribes, for he was a wonderful example of how a person whose background is quite ordinary may rise to great heights through diligence and royal favour. He grew up, I believe, in the small town of Iuny, and his parents were worthy but dull and far from rich. His schooling he had from an elderly priest who retired to Iuny to grow vegetables. He first came to the attention of the late Pharaoh Thutmose the First, may he live, through the Pharaoh’s architect, the incomparable Ineni, who identified the young Senenmut as a most promising student of architecture. He worked under Ineni’s tutelage for several years and the old man drove him hard.

Being a man of many parts, Senenmut was also an able administrator and furthermore good with children, so Pharaoh Thutmose the Second appointed him to be tutor to little Neferure who was born to Queen Hatshepsut when she was the Great Royal Wife, and also made him steward of the child’s property. Senenmut dearly loved that little girl and she loved him. He would bring her along on a trip to a new building site, but only if he was sure she would be safe. I often saw her sitting on his lap, listening intently to some story that he was telling with much drama, or giggling uproariously because he was tickling her. They were always laughing together. He had a finely developed sense of the ridiculous and could mimic pompous officials and priests with wicked vividness.

I remember how one day he was doing a fine imitation of Hapuseneb for the amusement of the child and several junior scribes, myself included, during a time of rest under some trees at Karnak, where a section was being added to the hypostyle hall on the orders of the Pharaoh. The two men, the scribe and the priest, were similar in some ways, mainly in being very competent, but utterly dissimilar in others, and they never got on well. That day Senenmut had tied a huge bush of some kind to his head to represent Hapuseneb’s imposing ceremonial wig, and was pretending to pray to the gods, while responding in asides to his wife Amenhotep. This lady, as everyone knows, rules the roost at home and the Grand Vizier and Chief Priest of Amen jumps at her commands.

“Blessings and thanksgiving to thee, O my Father, my Lord!” intoned Senenmut in the high-pitched, slightly nasal tones of Hapuseneb. “Hear my prayer! The earth waits for thy precious seed!” Then he added, in an aside to imaginary words from his wife: “No, dear, I have not spoken to the builder. He is still completing the alterations at the palace. Amenhotep, my dove, I am busy. The earth waits for thy precious seed! Come thou and inseminate it! No, my dove, I do not want you to live in a hovel. Of course not. I assure you …”

By this time everybody was laughing. The imitation was brilliant.

Senenmut was getting well into the swing of things: “All people sing thy blessings and praise thy name,” he prayed, in the very voice of Hapuseneb. “We must be patient, my dove. The pyramids were not built in a day, you know.” He did not notice that a group of priests had emerged from the pylon behind him and were fast approaching our resting place. Nor did he realise that the jeers and cheers around him had suddenly fallen silent. “O give ear to our pleas!” he wailed, clutching the bush to his head. “Be thou generous, be thou …”

At last a loud cough from one of the minor priests attracted his attention. Senenmut turned around, to be confronted by Hapuseneb in person. “ … merciful!” he said, tailing off. The bald, immaculate priest stood glaring at him with his arms crossed. Sheepishly Senenmut removed the bush and shook some leaves from his thick dark hair. He was as tall as the other, but rangy rather than elegant, and he was covered in dust from the building works. “Sorry,” he said, carelessly. “We were just … fooling around.”

Hapuseneb looked him up and down with a sneer. “And you are the appropriate person,” he said, his high-pitched voice even higher with anger, “to play the fool.”

“At least I do not have a wife who makes a fool of me,” snapped Senenmut.

Hapuseneb blinked twice. “But then you are the Pharaoh’s fool, not so? A flea-bitten base-born buffoon.”

I thought the scribe would strike him for that. He did make a forward movement, but then he restrained himself, with a visible effort. “Better than being a two-faced onion-eyed footlicker.”

At that they almost did come to blows, but two of the priests accompanying Hapuseneb laid restraining hands on his arms. “Vizier, come away,” one of them muttered. “This is unseemly.” With one last glare, the Vizier and Chief Priest turned on his heel and left the scene. Senenmut gave a yelp of laughter and the junior scribes giggled, but not too loudly, for it does not pay to anger such a powerful man.

Her Majesty, I observed, used to pit them against each other. She would often call upon them both to offer suggestions for solving a problem, and they tried to outdo each other with their advice. But in the end it was usually the Pharaoh who cut through to the core of the issue, and it was always she who decided what was to be done. There was never any doubt as to whose hand was at the helm of state.

I pray that her grip may never falter. That she may hold the Black Land safe.