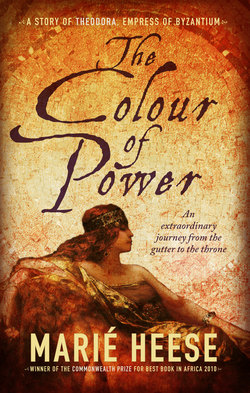

Читать книгу The Colour of power - Marié Heese - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 1: Exit Acasius

ОглавлениеHer very first memory was of a dancing bear. She loved going to the stable where the bears were kept to watch the training sessions, sitting quietly, entranced. The bear was taller than a man, taller than her father the bearkeeper; it seemed to loom almost up to the roof as it lumbered heavily to and fro, a dark, furred dancer, in a grotesque travesty of grace. The child did not think that, though. She thought that her father was a man of power, because he was the master of the bear. Clearly, the bear was very big, and very dangerous, but her father could make it do exactly what he wanted it to. So his power had to be even greater than the bear’s.

She sat on a bale of hay, dainty little feet dangling, and regarded her father gravely with huge, dark eyes. He concentrated with fierce intensity on the animal, gesturing boldly to keep it moving in time to the merry dance music his elderly one-legged assistant coaxed out of a fiddle.

“Hup!” he cried. “Hup, and two and three and four, this side, that side, hup!” She knew it was a black mountain bear from Illyria that had been trained by someone else before, and it was not easy to master an animal that you hadn’t trained yourself, her father said. But he had learned to work with bears when he was a child. That had been in another country. He used to visit his grandfather in a little mountain village, he told her, where there were Gypsies, and they had taught him their skills with wild animals.

She wrinkled her small nose. The place smelled powerfully: there was the rank scent of bear, her father sweating with effort and Ragu, his assistant, who always smelled sourly unwashed. Also, less pungent, the grassy smell of the bales of hay and the sawdust underfoot. A pity that such an interesting place did not smell sweeter, she thought. Yet she would come all the same, to bring her father his lunch and to watch him master the bears.

The assistant stopped playing and the bear stopped rocking, but still waved its heavy arms and whuffled through its nose.

“Well done, Bruno,” said the bearkeeper. “You are a good bear. You are the best dancer.” He leaned forward towards the bear, stretched his neck, placed his hands on either side of its head and raised his face so that he was intimately close to it. With great control he breathed right into its nostrils. So close, she thought, shivering with dread and delight. So close to such terrible teeth.

“Why does he do that?” she whispered to the assistant.

“Calms ’em,” said Ragu as he packed up his instrument. “And shows ’em who’s the boss.” His one good eye peered warily at the bearkeeper and the hulking animal. She knew that a lion in a hunting game had clawed his other eye out, right here in the Hippodrome; the same lion had chewed off half of his left leg. That was before the Emperor had banned hunting games altogether. The physicians that served the Hippodrome had managed to save his life, but, her father said, his nerve was gone.

“This breathing act that Acasius does gives me pains in the stomach,” said Ragu. “Man’s mad.”

“Do bears like dancing, Ragu?”

“Huh! No,” and he spat into the sawdust. “See, what the trainers do, they put a burning hot metal plate under the bear’s feet and they play a tune at the same time. The bear hops about to avoid the pain and cool its feet. After a while, when it hears the music, it starts to hop, pain or no pain. Then the trainer teaches it to keep time to the music.”

“Did my father do that to Bruno?”

“Nah. That was the trainer before him. Your father believes in other ways.”

Acasius patted the great bear and fed it honey-cake. “There! Now, off you go, into your cage, get along, get along, there’s a good bear.” The huge animal ambled away, rumbling softly to itself. The gate of its cage clanged shut.

“Come out and watch the next chariot race,” Acasius said to his daughter. “We can stand at the back where nobody will see you.”

She loved her father’s place of work under the vast Hippodrome, where the chariot races took place. Next to the Hippodrome there was the huge palace complex where the Emperor lived. Her father explained to her that the Imperial Palace was linked to the upper part of the Hippodrome by a corridor that led to a balcony, called the Kathisma, where the Emperor would sit surrounded by important visitors and by many men who served him, to watch the bears dancing, the tournaments and, above all, the chariot races.

“There is room,” said Acasius, “to seat one hundred thousand men.” The little girl looked at him, puzzled. “Enough seats for one out of every five people here in Constantinople to have a seat,” he explained.

She nodded solemnly. Five she understood. “We are five,” she said. “Father and Mother and Comito and baby Stasie, and me. Like my fingers.”

“Yes, dear.” He bent down and lifted her. She wrapped her legs around his sturdy body and he drew his cloak around them both. Respectable women were not allowed to view events at the Hippodrome, nor were monks and clerics, but he would smuggle his small daughter in to where they might watch, hidden, in a safe place. He strode out with her along vaulted passages fitfully lit with smoking torches and emerged into the sunlight at a vantage point below the Kathisma.

“We can watch from here. See, we’re right next to the area where the chariots are hitched up. We’re directly below where the Emperor sits. The start is over at the end, there.”

She peered through the fence at the support staff who laboured to hitch up the chariots for the next race. The unmistakable odour of stable, of horses and manure, thickened the air. Voices snapped orders, wheels crunched, horses whickered and whinnied. She could sense the heat, the tension and the power of the animals milling about: dangerous, surely – and so close! But she was safe. Her father held her safe. His arms were strong and the woollen cloak warm. He still smelled of sweat and bear, she thought. But he would stop off at the baths to wash before coming home for his dinner. Mother would not like him to come home smelling like this.

Just as they took up their place, the previous race ended and a roar went up. It seemed to the child that the sound wrapped itself around her like the cloak. “Oh!” she said and covered her ears. “What a noisy place!”

“The favourite has won,” her father smiled, “and so lots of people have made money.”

“I expect they are glad,” she said. She knew about money. Money was important and they never had enough of it. She knew that.

Workmen scurried onto the racetrack to remove the tangled wreckage of two chariots that had crashed spectacularly at the further bend. To distract the crowd, a gaudy procession now emerged from an arched entrance in one long side of the horse-shoe track: two white horses decked with bells and plumes galloped out in front, each with a trick rider who balanced bareback, jumped off, ran alongside, leapt up again, somersaulted, stood on his head, and generally defied death by trampling hooves. Next came a group that juggled flaming torches, then scarlet-clad giants on stilts; four ostriches with feathers dyed brilliantly green or blue dashed onto the track bearing small riders who clung perilously to their long necks; a squat dwarf in a golden tunic trotted out with a gilded crocodile on a kind of sled, acrobats cartwheeled, carried each other upside down, and formed a human pyramid which rapidly dismantled itself before the topmost little person could crash into the dust. Clowns in baggy stripes brought up the rear; they fell over, staggered, and whacked each other with huge flat weapons that emitted loud farting noises on contact. The little girl cheered and laughed with the crowd.

“Oh, I wish they would never stop!” she cried. But already the participants in the next race were in place behind the gates from which they would set off.

“Twelve gates, you see, sweetheart,” said Acasius. “One for each of the signs of the Zodiac. The heavenly signs, you know, for the months of the year.”

“I know, for when you were born. My sign is Aries, the sign of the Ram. Mother says so. She says it means that I am strong and one day I will be powerful.”

Acasius smiled indulgently at his small, pale daughter. “Yes, my sweet Theodora. And the circus arena is the earth. The Hippodrome is the navel of the world, the Christian Roman world of which Constantinople is the capital. The very centre. And when the Emperor sits in the Kathisma, he is seated …”

“… right at the centre of the world,” she finished, smiling with delight. “Is he there today, Father?”

“I believe he is. But we can’t see him from here, we’re directly beneath him.”

“What is his name? Does he have a name, like ordinary people?”

“Anastasius.”

“Oh! Nearly like Mother. And Stasie.”

“Yes. Also: Thrice August. And Basileus. And …” he whispered in her ear, “old Odd-eyes. Because he has one blue eye and one black.”

She giggled. “Maybe he sees one kind of world if he closes one eye and a different world if he closes the other one.”

“He shouldn’t see us at all,” warned Acasius. “Especially not if we think he’s funny.”

“But he can’t see us.” She snuggled into the cloak. She rubbed her cheek against his rasping chin. He would need a shave, too, before he came home. Her interested gaze took in more details of the huge stadium.

“There are snakes,” she said, and pointed at a column that glinted with bronze highlights in the sun. The intertwined coils ended in three ferocious mouths with vicious fangs. “But I’m not afraid.”

“No need. That is the Serpentine Column. Dedicated to Apollo, to celebrate a victory in warfare.”

The stands buzzed as the chariots for the next race moved into the starting slots. A trumpeter blew a fanfare and the starter gave the signal. The spring-loaded gates snapped up. The roar swelled as the teams of horses thundered out into the straight; their helmeted drivers balanced expertly on the light two-wheeled racing vehicles and cracked their whips in the air above their teams of four matched horses.

“But they’re tied up,” she said, surprised. “The drivers are tied up. What if there’s an accident and they fall?”

“Yes, the reins are tied around their waists. But they carry knives, to slash themselves loose if need be.”

“Why do they need four horses, for such a little cart?”

Acasius smiled at this term for a racing chariot. “Only the two in the middle actually pull it. The outside horses are lightly attached – they’re only needed for stability. Just look at those teams move! Marvellous animals, marvellous.”

“It must be fun,” she said, leaning forward to get a better view. “Especially if you don’t crash, and you win.”

He smiled again. “Indeed. You see those columns, along the spina, with stone eggs on top? At the end of each lap, one egg drops into a slot. That way everybody knows how many laps there are to go.”

“I see them, I see them! There! The first one dropped!” She jumped in his arms with excitement. “Look at that one go! Will he win, Father, will he win?”

Acasius laughed at her excitement. “Probably not, he’ll be the pacesetter for the Blues. He’ll stay out in front for a while.”

“Are we Blue or Green, Father?”

“Oh, Green, Green! I work for the Greens, remember!”

The Blue leader maintained his headlong pace for a second round.

Theodora could hardly breathe. “The Green’s catching up! He’ll pass, he’ll pass! Look!”

“No, his job is to jostle the Blue out in front, if he can. Then his team mate, who’s faster, can get by.”

“But that’s cheating!”

“No, just tactics. There! Did you see that?”

A howl from the stands greeted a near-crash as the Green edged nearer to the frontrunner. Both chariots rocked wildly.

“Oh, well held,” her father exclaimed. He stared intently as the two charioteers managed to avoid disaster. “Now watch that one coming up on the outside. That’s the Blues’ best driver.”

Delirious cheers urged the challenger on as he swept past the others and tore ahead.

“Nika! Nika!” echoed around the arena.

“What are they shouting?” the child asked.

“‘Nika’ means ‘win’. It means ‘victory’. They’re shouting: Victory! Victory!”

“Nika!” she shouted. “Nika!”

“Not when the Blues are ahead,” her father said. “Only cheer the Greens. Don’t back the wrong team, sweetheart.”

“We’ll pass again, won’t we, Father?”

“Watch our man try,” he agreed, and let out a yell in concert with a hundred thousand other throats as the champion driver of the Greens hurled his chariot forward to pass his team mate and the Blue pacesetter. But the Blue charioteer swept onward. The rest of the field were some distance behind the two leaders; they charged along choked by their dust.

“They’ll all try to keep to the left,” said Acasius, “but if their wheels touch the stone kerb, they’ll shatter, and the chariot will be done for.”

Round and round they stormed, the magnificent horses and the fragile chariots driven by men who looked slim and slight and almost disappeared amid the churning dust. She cheered their champion, together with the screaming supporters of the Greens who were dressed in shades of the appropriate colour, facing the tiered ranks of blue-clad supporters on the opposite side. But the foremost chariot was Blue and its driver clung grimly to the lead; never did he allow the Green driver a single chance to pass him by.

Five eggs had dropped.

“Two laps left,” said Acasius, watching intently. “Go, Green! Go, go!”

Now one of the less able charioteers drove too close to the kerb and a wheel shattered into matchwood. He was flung from his perch onto the tracks, a second chariot cannoned into his disabled one and both broke up. The second driver had managed to free himself from the traces with swift slashes of his knife and leapt onto the spina, but the unfortunate first driver was dragged among the frantically lunging, whinnying horses and was trampled by slashing hooves.

The child screamed with dread. Her father held her tightly. “They’ll get him out,” he said. “They’ll save him, don’t worry.”

The ground staff dashed across the track, risking their lives among the rest of the chariots that raced on. Clouds of dust partially obscured the chaos. Yet it was all too clear that the figure they carried off on a stretcher was broken like a pottery statue dashed to the ground, and stained from head to foot with red.

“Come on, come on, get it clear!” Acasius muttered.

The men worked at a frenzied pace to remove the debris and the wildly thrashing horses, but there was too little time to clear the track altogether before the last egg slotted home and the leading chariots tore around to battle it out in the final lap. The Blue driver, still in the lead, lost some speed as he dexterously avoided the obstacles in his path, going out wide. The Green tried to sneak past on the inside, but there was still some wreckage near the kerb and his left wheel struck it. This resulted in wild swings from side to side as he struggled to regain control. The supporters of both groups were beside themselves: they jumped up on their seats, waved their arms, and bellowed encouragement. The noise grew deafening.

The child thrilled to the roar of the crowd. She felt as if she could float on the noise. As if it might lift her up, might float her out of her father’s arms, right up to the Kathisma where the Emperor sat.

The Green driver had to haul his team almost to a standstill to avoid another disaster. The Blue charioteer had speeded up again and swept triumphantly ahead. She almost wept when he charged past the winning post. Around them some people hugged each other rapturously, while others howled in dismay.

“Father, we lost! We lost!”

“Never mind, we’ll win another time. Now come along. We must get out quickly, I’m not supposed to bring you here.” He strode back the way they had come, through passages now thronged with rowdy, excited punters. He held her tightly under the cloak. When they reached the main exit, he set her down.

“Can we go home now?” Her short legs were shaky.

“I must go and check on Bruno. He’s been a bit grumpy lately. If he’s not better by tomorrow, I’ll have to get the vet to see to him. I think it may be an abscess in a tooth, he’s been off his food.”

“Father … the driver … will he … Did he die?”

“He wasn’t carried out through the Nekra Gate,” her father said, “so he must have been alive. They’ll do their best for him. The Hippodrome has good physicians. I’m sorry you saw that. You go along home, sweetheart, you’re all right on your own, aren’t you? You’ll run all the way?”

“I’m fine, Father,” she said, squaring her shoulders. “I can do it.” She would thread a path among the cleaners, stableboys, grooms, animal trainers, food vendors, loafers, beggars, pickpockets and the many bettors, who would wager not only on the outcome of the races, but on the outcome of the marble game. Marble balls with the colours of the competing teams would roll down slightly sloping marble tables, towards the holes at the bottom. This game, her father said, required no skill and was a good way of wasting money. Still, she thought she would like to try her luck, only she never had any money to waste. You had to pay to make a bet.

Once outside, she did as her father said and ran all the way, her small sandalled feet kicking up the dust, which was largely dry animal manure pounded fine by the traffic. A cart would have watered it early that morning, but already the sun had baked it dry again. She liked the smell of it – together with the salt tang of the sea it smelled of home. On she dashed, past the grand buildings that lined the important middle road (the Mesê, it was called), past the huge bronze doors of the Imperial Palace where smart guards in fancy uniforms held their swords at the ready and winked when she sped by, past the Baths of Zeuxippus with the tall disapproving statues. She skirted the square in front of the Church of the Holy Wisdom with its towers as high as God. Ran on past rows and rows of pillars in front of shops that sold all kinds of wonderful things.

When she reached the Forum of Constantine she turned off the middle road onto lesser roads towards the Golden Horn where ships rode at anchor. Here rich people’s villas and simpler wooden houses stood side by side, all of them with tall crosses on their roofs. When she was smaller, she had found the forest of crosses frightening. But her father, who had been a priest in that other country where he had learned to tame bears, said they meant that Jesus was watching over her, over them all, and the crosses should rather make her feel safe. But she had seen some nasty things happen to people, in spite of the crosses. It was a world full of scary things, and she reasoned that Jesus couldn’t be watching everybody all of the time. So she trotted on as fast as she could, breathless now. She dodged vegetable carts, bleating herds of goats and sheep, porters, slaves on missions, off-duty soldiers in their green tunics, raggedy beggars, washerwomen with bundles, and sedan chairs in which rich people rode.

Nearer home the streets grew narrower, often no more than crooked alleys, more crowded and also darker, because the high tenement buildings blocked out the sun. She knew it was important to sidestep the piles of rotting garbage, not to breathe deeply, to watch out for peels that might make her slip, and to avoid being drenched by stinking slops emptied by housewives from windows above her head.

She stopped only once, to greet the blacksmith on the corner near their rooms, a man almost as big as a bear, who fascinated her because of his great strength and the way he casually handled red-hot metal, which he bent and hammered into any shape he wanted. She loved watching the horseshoes he fashioned sputter and hiss when he plunged them into water to cool them off.

“Afternoon, Tertius,” she called out in a pause between hammer blows.

He grinned at her, his teeth white in his swarthy face. “Afternoon, Princess,” he replied in his deep voice, with a mock bow.

She giggled happily. It was their joke, but she stepped more proudly after this greeting, skirting the buckets of pee standing outside Fat Rosa’s laundry, which took up all of the ground floor. Passersby were encouraged to fill the buckets up, because, Fat Rosa said, there was nothing like pee to get white stuff really clean. Theodora tilted her small nose as she avoided the disgustingly smelly area – many men had a poor aim – and finally reached the entrance to the stairs. Even if they did live on the top floor of an old building, she thought, even if they weren’t rich and didn’t travel in sedan chairs and had no slaves to look after them, the big blacksmith thought she was special. She knew that. She liked it. And she liked to be called Princess.

Anastasia was looking for Acasius. She seldom went anywhere near the stables where he worked, for she hated her husband’s job. It had no status. It was not very well paid. It was dangerous. And furthermore, it was a smelly occupation. Acasius, as he had chosen to call himself from when they arrived in Constantinople, was good about going to the baths before he came home, she had to grant him that – but Ragu, his one-legged assistant, smelled like a skunk and didn’t seem to care. Crossly she skirted a pile of dung in her golden sandals and lifted the skirt of her filmy tunic with a twitch. She was on at the Kynêgion in a few minutes, she’d be late, and there’d be trouble. But she had to find him, to tell him that the Emperor himself had ordered a special performance by the dancing bears to be put on directly after the last race, to entertain the visiting governor from Cyrenaica. There was no sign of either of her elder daughters, or she would have sent one of them.

As she reached the stable at the back of which the bears were caged, she pushed the half-open door aside and stepped into the gloomy interior with its feral smell.

“Acasius,” she called out sharply. “Acasius?” No response except a low, rumbling growl. She blinked in the semi-dark, blinded after the brilliant sunlight in the courtyard she had just crossed. A dark, hulking shape against the furthest wall moved. As her eyes adapted she recognised Bruno, the biggest of the bears. The smell in here was truly dreadful, she thought. It was …

Blood. There was a pool of blood on the floor and it flowed sluggishly towards her elegant small feet. Bruno had something in his paws, and he was chewing on it, rumbling in his throat. It was an arm. No, that couldn’t be right. She could not believe … he couldn’t have …

Against the white wall she made out her husband’s pale face, his dark eyes ghastly with terror. His shoulder was a gaping wound from which blood spurted in pulsing scarlet gouts. Crunch, went the bear. The pool of blood reached her squeamish toes. She drew in her breath, and screamed.