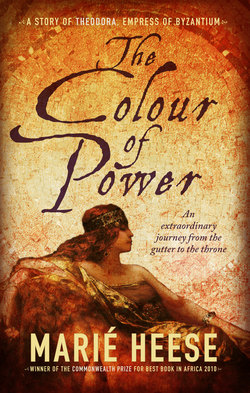

Читать книгу The Colour of power - Marié Heese - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 2: For whom the trumpet sounds

ОглавлениеAnastasia’s screams brought Ragu limping to her aid as fast as he could on his peg leg, followed by a guard who sent for a physician and a veterinarian. Ragu snatched up a pitchfork and began to prod the bear away from Acasius, who was barely breathing, towards the open door of the cage. The guard helped with a broomstick. The tormented bear roared. The sound reverberated in the confined space. It was a sound for the outdoors, that spoke of freedom, of fresh air and sweet breezes, of the open plains of Illyria.

The sound frightened Ragu and the guard even more and they attacked the bear with greater vigour. Between them they forced the huge animal to shamble into its cage. It sat down as the door crashed shut and the bolt shot home, rumbled angrily and refused to give up its trophy: the ragged remains of its tamer’s arm. As it continued to chew, white fingers appeared to flap in an obscene gesture of farewell. Anastasia leaned against the wall and vomited.

Next to arrive at a trot was the physician. A bald, muscular man accustomed to trauma, he took one look at the scene and leapt forward. He put his hand right into the open wound and probed amid the pulsating blood which soaked his arm and bespattered his tunic.

“Where … come now … come now … got it! You with the broom – go and call another physician. Tell him we’ve got a man bleeding heavily, he’s to bring a stretcher. I’ll pinch the blood vessel. Be quick!”

“Can you … is he …” Anastasia could hardly speak.

“You are his … wife?” She cringed beneath the man’s contemptuous glare that raked down from her heavily painted face over her diaphanous tunic to her golden sandals. It said, as clearly as words could have done: I see that you are an actress and therefore a whore.

“Yes,” she said. “Can you save him?”

“We’ll try. I’ve seen worse. But he’s lost a lot of blood and he’s in shock. We’ll move him to the sick bay. Can you come with him?”

“No,” she said. “I’m due to appear in the Kynêgion any minute, in the Pantomime of Pasiphae.” She could not afford to lose her job, so even when her husband lay bleeding to death she had to hurry down the road to take the stage as the Cretan queen Pasiphae who became enamoured of a bull. This mythical tale was one of the Emperor’s favourites and she had to perform it often.

Usually she enjoyed the roar of admiration that echoed around the amphitheatre when she made her entrance enveloped in a silver cloak, a glittering diadem in her long chestnut locks: Pasiphae, daughter of the sun, moon-goddess and sorcerer, wife to Minos, King of Crete. This day she did not hear it. Nor did she see the ranks upon ranks of men. She must have made the correct moves, for there were no boos. She must have started at the sight of the grand white bull, sent by the god Poseidon to assure her husband, Minos, of his right to rule the Cretan kingdom. She must have shown her horror as Minos made the fateful error: he replaced it on the altar with a lesser animal and sent the marvellous bull to join his herds instead of sacrificing it as was proper.

She had so often acted the role, so often demonstrated the queen’s obsession with the great white bull, brought about by Poseidon’s curse to punish Minos, she had so often played the seductive strumpet, she had seduced the bull so many times, that even today, when she moved without thought, without volition, she convinced the audience. Slowly she removed the cloak: tease … pause … pose. Gracefully, now down to her semi-transparent tunic, she discarded the diadem and handed it to a waiting slave, then the bracelets, one by one. She caressed her white arms as she did so. Then she delicately peeled the tunic from her shapely body – to the accompaniment of raucous applause and shrill whistles – and dragged it in the dust. She tossed her golden-brown hair. She drew the tresses over her pointed breasts with their red-painted nipples in a pretence of shyness; she titillated the avidly watching men, made them hot and hard with desire, made each one of them wish she was seducing him and not the mythological animal.

While all she saw, what blotted out everything else in her consciousness, was the white face of her husband huddled against the stable wall, the spurting blood, the white fingers waving a grotesque farewell, and all she could hear was the bear going crunch. She maintained her composure, except when she removed the second sandal and it fell to the ground sole side up, and she saw that it was stained with blood. Then, she screamed.

But her scream coincided with the bull prancing back into the arena: two men beneath a cover of white leather, with a huge horned head that tossed as it cavorted around and around, and the audience assumed it was all part of the fun. How they laughed when Daedalus provided the wooden simulacrum of a cow, into which she had to climb through a gate in the rear, lie down and insert herself with her bare legs protruding from the front, so that she could couple with the bull! How they whistled and stamped when the actor who formed the front legs of the bull activated the spring that caused its huge member (also leather, stuffed) to spring erect! And how the amphitheatre echoed to the roar when the bull pushed his vast member into the cow!

There was a slot under her buttocks that allowed the bull to enter the cow, with a great production of the act of coitus while she kicked her legs in feigned orgasmic delight. Usually she managed to distance herself from this performance and feel nothing more than mild contempt for the men who enjoyed this coarse mime. Mostly she was simply bored: it was a job, she did it and she was good at it. She had her fans. But today, when all she could see was a white face and gouts of blood and a white hand obscenely flapping, today she lay in the uncomfortable wooden box that smelled dank and stuffy, with the bull bumping up against her and thousands of voices cheering it on, and she felt violated.

When she descended from the shell of the cow, it took all her resolution to remain on her feet and register appropriate horror when the monster to which she had supposedly given birth cantered onto the scene: Minotaur! Half man, half bull. Head of a bull, lower parts of a man. Also, of course, naked and well hung. Indeed, she, the Queen, had been properly punished for her bizarre act. No matter that she had been guiltless. No matter that she had been cursed for her husband’s foolish evasion of his duty. She had lain with an animal, she was disgusting and depraved and she deserved her punishment. Off she went in tears, followed by howls of righteous contempt.

She dressed hurriedly and ran all the way to the sick bay at the Hippodrome. The physician met her at the door, wiping his bloodied hands and forearms.

“How is he? Is he …” She fought for breath.

“He’s dead. You’re too late.”

“No,” she said. “No. Not just … without … not …” She put a hand against the rough stone of the wall to keep herself in the world, to stop herself from falling into a dark void.

He was unable to look her in the eye. She sensed his disapproval of this woman who performed a lewd pantomime while her husband breathed his last alone. “We tried, but the shock and loss of blood were too severe,” he said. “It was a frightful wound.”

“Oh, dear God,” she said. “He loved that bear. He used to breathe into its nostrils. Right up close.”

“The bear’s had to be put down. No tamer will work with an animal that has attacked someone so viciously. Vet says, it had an inflamed abscess in a tooth that probably drove it mad.”

“A tooth,” she repeated.

“Yes, well, it’s a pity. It was a valuable animal. Trained bears are hard to come by. But there it is.”

She left the sick bay on listless feet, wrapped in her own old cloak. On the way out she encountered Peter, an apprentice trainer who had had a great admiration for Acasius.

“I’m s-sorry, Anastasia,” he mumbled and shuffled his large feet. “I heard. It’s t-terrible.”

She nodded. She did not trust her voice.

“I’ll s-see you home,” he offered. “You must b-be exhausted.”

She nodded again. Let him bumble along, as long as he didn’t expect her to speak. She would have to tell the children, she thought. Dear God in heaven, how would she do that? They would be shattered. Especially Theodora, the middle one, who had without any doubt been her father’s favourite, and the last one to see him before he died. What could she say?

And now, bereft of their main breadwinner, how would they survive? She was, she told herself in utter disbelief, a widow. She had three small girl children. She could not imagine what would become of them.

Theodora looked at her father as he lay in the open coffin, wrapped in his best cloak in such a way as to conceal the fact that his arm was missing. His thick, dark hair was beautifully combed and his face looked stern, the way he used to look when one of his children had been naughty. There was a peculiar smell, in spite of the masses of flowers that breathed scent into the air, despite the incense that wafted from the censers carried by the priests who had come to lead the procession to the cemetery near to the city walls. It smelled like standing water, she thought. It smelled like the dead mouse they had once found in the kitchen. It had been days ago that he was killed.

She knew that her father had died. She knew that. Yet she thought that maybe, if she could be alone with him and speak to him very nicely, tell him how much they missed him and how sad they were, he might open his eyes again and smile. Miracles did happen.

Her father had told her about miracles himself, for he had been a Christian priest before he was a bearkeeper, in that far country from which they had come when she was too small to know that they were leaving home. Every evening at bedtime, he had read to his daughters from one of the two precious books – codices he called them – that he had brought with him. One told how God had created the world – Comito’s favourite – and the other held the Gospels, that told about the life of Jesus of Nazareth. Theodora loved that one. Her father had read her the story of how the Lord Jesus had spoken to Lazarus, and he had awoken even though he had been dead for days. Even though his winding cloths were smelly. So perhaps …

But she was never alone with him. There were lots of people: Asterius, the tall, thin Dancing Master of the Greens, with the big nose and important air, who was in charge of all their performances at the Hippodrome and the Kynêgion, also men Acasius had worked with, neighbours from their block and others down the street, the men friends with whom Acasius had wrestled and played ball games, the baker who supplied their bread, the blacksmith, who looked unnaturally clean, and Peter, who had liked to watch Acasius working with the bears, as well as Rosa, the sweaty fat washerwoman from downstairs, who had a clear, sweet voice and led the mourners in song.

Theodora looked forlornly into the coffin. She saw that they had put his training whip and pitchfork into the coffin with him. And his handsaw and his hammer and … and … his whittling tools, which he had used to make little animals for her. Now she understood for the first time that he was never going to wake up. Never coming back. Never again going to hold her warm and safe in his cloak. They were really, really going to put him into the ground. There would be no miracle. Fat tears rolled down her cheeks.

Now several sturdy men who were to carry the coffin came into the room. One had a hammer. It was time to close the lid. Theodora wanted to shout: No, no, don’t close him in – don’t shut him up, don’t, oh please don’t take him away! But her mother took her hand in a grip so hard that it hurt. It was going to happen no matter what. She clung to her mother’s hand and winced at each hammer blow. But she said nothing.

The men hoisted the coffin onto their shoulders and bore it out of the door. A procession began to form up in the street. The priests chanted, words she did not understand. But she did understand what the choir of women mourners sang as they trudged along. It was an old song that she had often heard women sing.

Once in my garden there grew an apple tree

But a storm blew up and stole it away from me.

Once in my garden I had a lovely rose

But the petals were torn by the winter wind that blows.

Once in my chamber I lay safely with my dear

But now when I call him my beloved cannot hear.

Once we could stand side by side and see the sun

But now your fair eyes are closed and I am left alone.

Yes, I am left alone and I weep for my lost dear.

I call him and I call him but alas he cannot hear.

My heart burns, my heart burns, for alas he cannot hear.

Her mother kept her grip on Theodora’s hand. Her elder sister, Comito, white-faced but dry-eyed, clutched her mother’s other hand. Their mother led them out into the street. An elderly neighbour who could not walk as far as the cemetery would look after their little sister, also christened Anastasia but called Stasie, whose short, fat legs would not carry her that far either. The solemn procession wound through the streets. The priests swung their censers and intoned their chant. People respectfully stood still and made the sign of the cross as the funeral procession passed by. A huge load of bundles that appeared to be walking on two legs turned into a porter who moved aside. For some time they walked through narrow, winding streets thronged with buildings, then they reached the outskirts where the road was lined with orchards and market gardens. A farmer with a donkey cart piled high with cabbages drew up and doffed his cap. Theodora’s tears had dried and she began, in a way, to enjoy the walk. She liked being the centre of attention. She liked having the right of way. It made her feel important.

But long before they reached the outer region of the city, where there were only stretches of untilled land covered in bushes and weeds, her legs began to ache and she felt desolate again, and when they finally came to a halt at the cemetery with its rows of slabs like beds of stone, she was once more in tears. The men manoeuvred the coffin into place. The priest spoke words that blew away over her head. No miracle, she thought sorrowfully. The Lord Jesus hadn’t made a miracle.

She looked up at the colossal ramparts, the thick walls that ringed the city, part brick, part stone, edged with moats and crowned with tall towers at intervals. The Walls of Theodosius, her father had told her. The figures of the guards on watch looked small against the massive battlements. The mourners chanted as the coffin began to sink into the gaping hole. Fat Rosa’s voice soared into a piercingly sweet descant above those of the rest of the choir. Then, just as the grave-diggers bent to their shovels and the first clods thudded onto the coffin, the harsh, brassy notes of trumpets rang out.

Theodora whispered to her mother: “How do they know?”

“What? How do … who?”

“How do they know Father is being buried now? The trumpet-players?”

“No, sweetheart, it has nothing to do with … with this. It’s a fanfare for the changing of the guard up there,” the widow whispered.

“Oh,” she said, disappointed. “I thought it was for Father.” She felt that there should be something more than men simply shovelling in earth. They should have meant the fanfare for him.

At last it was all done. Now there was the long road back. Theodora sighed and began to trudge, dragging her feet. It suddenly seemed a very long way home. And she was the smallest person in the whole procession. It wasn’t fair. Then a large hand enfolded hers.

“T-tired, little one?” It was Peter.

“Yes.” She could not keep her voice from quavering.

“C-can I carry you?”

She peered up at him. “Yes, please?”

His powerful arms grabbed her and she let out a shriek as she found herself hoisted right up into the air and settled on his broad shoulders with her legs dangling down his chest.

“Hold on to m-my hair,” he advised, and she clutched at his wiry brown curls that smelled a bit like dog. He held her ankles and strode forward. Ah, this was good, this was the way to travel! Better than a sedan chair, she thought triumphantly. Now she was high up, almost as high as the crosses on the roofs, and she could see over the fences and into windows and clear across the orchards and fields. She could see a woman kneading bread in her kitchen and another one milking a cow in her back yard and others drawing water from a well. She could see a man chopping at weeds with a hoe. She could look down on all the mourners, even her mother whose wavy hair, worn loose as a sign of mourning, bobbed on her shoulders, and she was much higher than Comito, who was always taller than she was because she was older and grew faster anyway. She thought: I am higher than everybody. Even higher than the priests. She wriggled with delight. Peter tightened his grip.

“Be c-careful,” he said. “You don’t want to f-fall.”

“Oh no,” she said. “Oh no. I’m holding on. Tightly.”

“What are you going to do?” Fat Rosa sat in their front room and fed Stasie bread soaked in milk. “Do you have family that might support you? Parents or a brother maybe?”

“Nobody,” said Anastasia shortly. Rosa irritated her, but she could hardly afford to make an enemy of her. The woman meant well. And she helped with the children. “This is not our city. It is not our country, in fact. We … we came from Syria. My husband had a brother who lived here, he was a businessman, he had a house … a good house, we thought he might have room … while we … but …” She struggled to control her breathing.

“Ah. Well, what about him?”

“He’s dead,” said Anastasia. “He died just before we arrived, he and his wife both, of a flux, they told us. Some said a servant they had angered poisoned them, but I suppose it was just … bad water, or something. Anyway, they were dead. Acasius managed to get the job at the Hippodrome.” She didn’t add that it was her last few gold coins, which she had sewn into her cloak when they fled, that had helped to convince Asterius of her husband’s suitability for the post.

“And there’s no one else? Not even a cousin?”

“Not a soul,” said Anastasia.

“Mmmm. I suppose you don’t earn enough yourself to keep out of the almshouse.”

“No,” said Anastasia.

“Convent for the girls, then. Or adoption, perhaps? It’s lucky they’re pretty,” observed Rosa judiciously, combing her fingers through Stasie’s brown ringlets. “Somebody’s sure to want them.”

“No!” yelled Anastasia. “No, and no, and no! I’ll not go to the almshouse, I’ll not go to a convent and I’ll not give my girls away!” She glared at Rosa.

“Well, excuse me, I’m sure,” said the woman, affronted. “I was just–”

“We’ll manage,” stated Anastasia. “Church charity will help. Even if I am an actress, and everybody thinks I’m a whore as well, I’m still a member of the church. And … I’ll … I’ll … think of something.”

Rosa had set the child down and hauled herself to her feet. She looked Anastasia up and down with a leer. “I’m sure you will,” she nodded and departed majestically. “Oh, no doubt, you will.” An aroma of soap and the goose grease with which she rubbed her hands remained behind.

“Cow,” spat Anastasia, and hurled a milk-jug at the wall. Stasie began to wail. Her mother gathered her up and held her tightly, rocking and hushing her. She didn’t feel able to cope with one of the child’s full-blown attacks of misery. Despite her brave words to Rosa, she had no idea what she might do. The steady centre of her precarious world had been ripped out. She had to hold the tattered remnants together with an act of will. Each night since her husband died, she had lain in her empty bed, alone and lonely, trembling with longing, helpless with fear.

Now she was suddenly filled with fury. “How could you do this to me, Theophilus?” she groaned aloud, using the old name for Acasius, his real name, the name that had belonged to a Syrian Christian priest who was a man of substance with standing in the community, not a lowly bearkeeper who earned barely enough to keep them from penury. Who had to humble himself before an upstart like Asterius the Dancing Master. Who had been torn to pieces by a bear, when he should have known better than to go so near to it. “Oh, God, I should have had a son!”

Comito, her eldest daughter, who had just turned six, looked at her with tears in her eyes. “Will we have to be adopted, Mother?” she asked fearfully. “Will we go to a … to a kind family? Will we?”

With Stasie on her arm, Anastasia dropped to her knees next to Comito and Theodora where they sat side by side on a narrow cot against the wall. She gathered all three her small daughters to her and inhaled their warmth, their scent of milk and bread and the goat’s cheese that had been their supper. She buried her face in Comito’s hair, a tousle of chestnut curls so like her own. Her hands curled themselves around the arm of one daughter, the solid little leg of another, as if to prevent them from being torn away that very minute. She would not allow it. Would not. She could no more survive losing these children than Acasius had been able to survive losing his arm.

“You will go nowhere,” she said. “We will find a way to stay together.”

“Promise,” said Theodora.

“I promise,” said Anastasia.