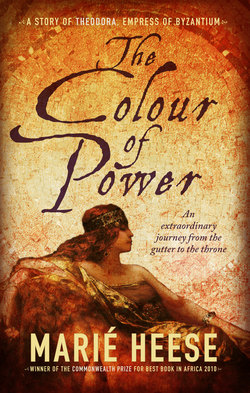

Читать книгу The Colour of power - Marié Heese - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 4: A scarlet scarf

ОглавлениеWeary and bereft of hope, Anastasia turned to go. She had tried her best. She had been daring and courageous, but it had not worked. She had been humbled. She had been punished for her audacity. It was over.

“Come, girls,” she whispered.

The terrible silence dissolved into a new buzz, a low murmur. Asterius sat down and arranged his cloak with a hugely satisfied smirk. He folded his arms again and stared around him complacently.

Then the unexpected happened. The man who served the Blue faction as Asterius did the Greens rose to his feet. His raised right arm demanded silence and the right to be heard. He quelled the chatter authoritatively.

“Wait!” he cried, in stentorian tones. “This is not right!”

Anastasia turned back, surprised.

“Advance,” he called and beckoned them over.

She straightened the garlands on her children’s heads. Stasie had begun the desolate weeping that was hard to stop. Let her cry, thought Anastasia. She’s the littlest one. Let her cry. Perhaps it may move them as my words could not. She led the trio across the wide expanse of dust towards the front rows of the Blues.

Their dancing master still stood. What was his name? she thought. She knew him, they had spoken more than once. Marius – that was it. He spoke again, projecting his voice to address the multitude.

This woman has called you

Most Christian and glorious, oh Greens.

But you have been neither Christian nor glorious today.

Anastasia was surprised. Normally Marius was a fussy, effeminate fellow. But today he had a dramatic presence, and the audience was with him. There was a rumble, part laughter, part hum of agreement, from the crowd. He continued:

Here we see the children of Acasius

Bereft of their father, begging for mercy.

Mercy they have not received.

The crowd rumbled again. He gestured towards Asterius.

These supplicants have put their case.

They have been received with arrogance, with silence.

He pointed dramatically at Asterius.

You, you who have not spoken with mercy,

Who have not shown Christian love –

May God silence your voice.

Asterius looked furious. Marius continued:

The plight of these three lambs, these innocents,

Must surely move the hardest heart.

“Throw up your arms,” hissed Theodora to her sisters, who stood and gaped at this new development. “Do the supplication! Then kneel!”

They did this as gracefully as they could. Marius nodded. He went on:

Their mother has not begged for charity.

She has merely pleaded for justice.

She has a husband who has useful skills.

He has been dismissed – for no good reason.

The rumbling assent grew louder. Many of the Blues directed disapproving glares at Asterius. He stared straight ahead of him.

But the illustrious Blues, as true Christians should,

Will give succour to these innocents in need.

We will stretch out our hands and dry their tears.

Anastasia wondered what would come next. Marius waited as the attention of the vast throng focused on him, Greens and Blues alike. Then his voice became more businesslike.

Our keeper of the bears is old, he wishes to retire.

We can use the strength and talents of a younger man.

He turned to face the tiers of men clad in blue cloaks that lined half of the Kynêgion behind him.

“Are we agreed?” he shouted, throwing up his arms. “What do you say?”

“Yes!” roared the Blue faction, and they drummed their feet loudly. “Appoint him! Down with the Greens!”

Anastasia was amazed at the sudden reversal of their fortunes. She had not thought that Marius, who was not as imposing as Asterius and much less arrogant, would have the courage to take such drastic action with such decisiveness. But she knew that he had suffered belittlement and scorn from the older dancing master, and he had seen and taken a marvellous opportunity to make the other look a fool – worse than a fool: greedy and lacking in Christian values.

She stepped forward and sank to her knees with her hands together prayerfully, her head bowed. “We thank the noble Blues,” she said, clearly. “We are most grateful for their Christian grace.”

The little girls imitated her gesture. The Greens growled. The Blues cheered.

“Girls, go home to Rosa,” muttered Anastasia. “Leave me to sort out the contract. Go now, leave, before the show begins.”

The children walked out hand in hand. Comito waved. Stasie had stopped weeping. Theodora gave a little skip. They had been saved, beyond all expectations, by the Blues. They could stay together, they would not have to be sold, or go hungry.

But all of them would henceforth hate the Greens.

As the weeks went by, their lives improved to some degree. As a beginner Peter did not earn a very big salary, but with the money their mother brought home they could keep going. Anastasia insisted that the two eldest girls should continue with the lessons that Acasius had begun with before he died. “Right now,” he had said, “it’s true that your prospects don’t look very promising, but you never know what the future might bring. You might advance in life, and my daughters should be prepared to take their places in better society.”

They could certainly not afford to hire a slave pedagogue, as more well-off families did, but Anastasia herself could teach them to read, write and reckon. In her previous life, of which her children knew nothing, she had been well educated. She could pass that learning on, which was fortunate. So whenever she had a free afternoon, their small table became a desk. The library in a better part of town loaned her codices; in her best cloak, her face wiped clean of make-up, she pretended to be a lady’s maid sent by a respectable matron with a love of reading.

Both girls were quick and able, but Theodora, especially, loved to learn. She was entranced by marks on parchment that miraculously told one stories, over and over, patiently, and even more astounded that she could make such marks herself. That such marks could turn into her own voice, speaking her very words. Also she loved numbers that followed each other in a particular order, that could be counted on to be predictable, that always came out in exactly the same way if you did specific things. Comito learned what she had to, quickly but without particular enjoyment.

“All the same,” said Anastasia, “you’ll likely both have to follow me on the stage. For that you’ll need to be trained.”

Fat Rosa was paid with honey-cakes to teach the girls to sing. Comito’s voice rang strongly, sweet and true, and she practised daily. “Can I have proper dancing lessons too?” she demanded.

“You’ll begin when you turn eight,” promised Anastasia. She understood that Comito’s one desire was to be the centre of attention, a special person instead of a little-regarded child.

Theodora’s ear was good and she could hold a tune, but her voice, though sweet, was small. Fat Rosa sighed and shook her head. “This one won’t be a star,” she told Anastasia. “I’m doing my best, but the voice is not impressive. And she’s so thin, and pale, and dark. She’ll not have the men on the edges of their seats. Comito, now …” Comito had the chestnut hair, burnished with brushing, lightened with lemon and bleached into a shining mane by sitting in the sun, that a future star of the stage should have.

Theodora said nothing, but she brooded about it. It was true that she could neither sing nor dance as well as her sister. But she wanted to be better than Comito at something. Something that Comito couldn’t even do at all. Something special, that was her thing. What this might be was at first not clear. Then one day, while she was waiting for her mother to finish a performance at the Kynêgion, Theodora saw a group of acrobats practising their stunts in a yard off to the side. It was a family show, with a father muscled like a statue, a limber, apparently boneless mother with a long plait of hair, and three nimble children who tumbled about and flung themselves through the air with joyous abandon.

Yes! thought Theodora. I want to be able to do that. I could do that. That could be my thing. She walked up to the father when he stopped to draw breath after a series of intricate tumbles. “Please,” said Theodora, “please will you teach me to do that?”

The man looked at her in amusement, his knotted arms and barrel chest slick with sweat. “It’s not as easy as it looks,” he said. “It’s actually not easy at all. It’s bloody hard work, and it’s dangerous.”

“I could learn,” said Theodora. “You needn’t teach me for free. My mother makes wonderful honey-cakes.”

He gave a loud guffaw. “No, child, we can’t get fat. Tell me … your mother … is she the actress who does Pasiphae?”

“Yes.”

He nodded thoughtfully. “So it’s your father got killed by a bear?”

“Yes.”

He asked: “Can you do a handstand?”

“Yes,” said Theodora, and she did, balancing upside down for several counts.

“All right. We’ll teach you. If you’re good enough, you can be a permanent stand-in. Sometimes one of the kids is not so well. But no complaints. You’ll do as you’re told. And you’ll practise, and practise, and then practise some more.”

“Yes, I will,” said Theodora, delighted.

She was less delighted when she found out just how hard it was. But she stuck to it; she stubbornly and wordlessly endured bruises, falls that whacked the breath out of her body, aching muscles, several sprains and a broken toe. And she learned: balance, suppleness, speed, control. Timing. Self-belief. Until at last she was good enough to be a part of their act. Good enough, in fact, to be the apex of the human pyramid that was the climax of their performance. Only she never had a chance to do this on stage, since the three children jealously clung to their places. Still, she knew what she could do. And one day, she thought, her chance would come.

Life was not all learning, though. They did have time to play. Theodora was quick and light on her feet and good at skipping. She could win races unless the others were much taller and had longer legs. But the game she liked best of all was the Emperor game. Someone in the group of children who took part hid a scarlet scarf which represented the purple which only the Emperor was allowed to wear, and all the rest had to search for it. Whoever found it, tied it on, and became Emperor for the day. Everyone had to serve and obey the Emperor.

Theodora had never before been the one to find the magical scarf, but one day she did find it, hidden under a stone beneath a drainpipe. A narrow edge peeped out at her, a rim of scarlet in the grey background. She pounced on it.

“I’ve found it!” she rejoiced. “I’ve found the scarf! Now I’m the Emperor, and all of you must serve me!”

“You’re just a girl,” objected the scrawny son of the blacksmith, who was as small and thin as his father was tall and muscular. “You can’t be Emperor.”

“Nonsense,” said Theodora, and she looped the bright piece of material around her neck. “There’s no such rule. I have the scarf. I’m Emperor.” She stared the objector down haughtily. “And the first thing you people have to do is to build me a throne.”

Several of the boys grumbled, but such was the power of her black-eyed glare that they did begin to cast around them. They were playing on an empty lot at the end of the street opposite the blacksmith’s shop, with a railing to which horses were often tethered in the shade of a somewhat spindly tree. But there were no horses today.

“In the shade,” said Theodora as she tapped her small foot. “And hurry up about it.”

“Well … we could tip the rain butt over,” suggested the scrawny one. “It’s empty. She could sit on its bottom.”

They up-ended the butt and crowned the new emperor with a garland of yellow flowers picked from a nearby bush – a weed, but no matter. She ascended the throne with the aid of a box that served as a step, folded her hands in her lap and surveyed her kingdom. There was rather a lot of manure about. “This palace needs to be cleaned,” she said regally. “See to it at once.”

Ordered from above, according to the rules of the game, her minions swept her domain with branches.

“Now I should like something to eat,” said the monarch. “Something sweet.” A small girl dutifully brought some dates, which Theodora ate slowly and daintily, ignoring pleading looks. As the afternoon wore on, the game continued: she commanded, they obeyed. When she demanded to be entertained, everyone shared in the jokes, the stories and the laughter.

Finally she clapped her hands. “Now then,” she said, “bring me a goat.”

“Why?”

“Because I want one.”

Her subjects stood in a circle staring at one another. “No! I’m not playing any more,” said the scrawny one. “Go find your own goat. Enough is enough.” He turned to go home.

“You come back here,” ordered Theodora. “I have not dismissed you!”

“This game,” snarled the boy, “is over.” The rest giggled and backed away from her, bowing in exaggerated submission. Then they all fled, their mocking laughter fading down the street.

Theodora was furious. She climbed down stiffly and walked home, still clutching the scarlet scarf. She had decided to keep it. They shouldn’t have it back. She hated to be laughed at.

“Where were you?” Anastasia asked. “What were you playing at?”

“I was the Emperor,” she said. “But they didn’t want me any more. They ran away.”

“Were you a good emperor?” Anastasia ladled out the vegetable soup she had made for supper. It was fragrant with herbs and smelled delicious.

Theodora blinked. In her mind, an emperor was an emperor: a person with all the power who could order everyone else around. A good emperor?

“What makes an emperor good?” asked Comito, hungrily spooning up soup.

“They’re a m-mad, b-bad lot,” grunted Peter with a mouth full of bread. “M-murder their m-mothers. M-make people worship their horses.”

“No, no, they’re not all like that, that was Caligula. He was crazy, yes,” said Anastasia. “But our emperors are Christians now. A good emperor must be close to God. I would think that’s the first thing.”

“Close to God,” Theodora repeated thoughtfully.

“And a good emperor serves the people,” Anastasia went on. “Stasie, you can’t eat soup with your hand.”

“I thought the people are supposed to serve the Emperor,” Theodora said with a frown.

“Well, yes. But the Emperor has a mission, which is to rule well and wisely, to ensure justice and make the kingdom great. So you see, he serves the people too.”

Theodora ruminated on this until she had finished her supper. “Mother, where’s my box?” she asked. She wanted to hide the scarlet scarf before she was made to give it back.

“Box? What box?”

“My sandalwood box. Father used to keep his sharp knives and small tools in it,” said Theodora. The tools had been buried with Acasius, but there had not been room for the box inside the coffin.

“Oh, that box. I gave it to Peter,” said Anastasia. “He needed a box for something.”

Theodora stood and glared from her mother to her stepfather, who was slurping up his second helping. “That was my box,” she said, furiously. “That was my father’s box, and now it is my box, and you had no right to give it to him, and he has no right to have it.” Angry tears glittered in her dark eyes. She had been mocked, and now she felt suddenly, deeply wronged. Her chest heaved with sobs and her voice rose. “He is not my father,” she said passionately. “He came here … he came and he … he takes up all the space, and he uses our father’s things, and he talks too loudly, and he eats too much, and he … he is not my father! And he can’t have my box!” Furious tears streamed down her face. She stamped her foot. “It’s my box! Mine! Mine! Not his! Not his!”

Peter was shocked to be the sudden focus of such grief and animosity. “I d-didn’t know … I’ll g-give it b-back,” he said, humbly. “I’m s-s-s-s-s-s …” His throat worked to no avail.

“Hush,” said Anastasia, alarmed. “Theodora, calm down, behave yourself! You have been extremely rude!”

Theodora wept inconsolably. A suffocating wave of sorrow had engulfed her, at the thought of the tools put away in the coffin, next to the stern face she had loved so much. He had not been stern with her. He had loved her and protected her and taken her to the Hippodrome with him and told her stories and made her wooden toys. And now he had gone, and he would never come home again. Never. Never. She was wrung with longing, and with anger at the interloper.

Comito began to look weepy too. Stasie’s round brown eyes also filled with tears and her lower lip wobbled. Loud, cross voices always made her cry.

“Oh, God,” said Anastasia desperately, and picked up her youngest, who at almost four was amazingly solid, like a small bag of sand, and too heavy to carry around, although she still constantly wanted to sit perched on someone’s hip.

Peter, clearly overwhelmed by the level of female distress in the small room, got up abruptly and walked out.

Anastasia sat down on the narrow cot against one wall with Stasie on her lap, and dissolved into tears herself. It was too much. She had tried to hold it all together, but it was too much. She was so tired. And now Peter was probably angry, as he had every right to be. He did his best, he was good to them all. It wasn’t his fault that his salary was not enough. He gave it all to her. He was loving and faithful and he was devoted to her.

But he would never understand that this very devotion was hard for her to bear, that it was burdensome. Theodora in her fury had said things that Anastasia also felt: He did take up too much space. He was too big, too loud, too demanding; his very devotion, his humility, his unqualified adoration made demands on her patience and on her ability to respond. She was too old for him, she thought. He should have had a much younger woman who had not yet borne children and who had strength and desire to match his. She couldn’t. She felt used up. Hot tears dripped into Stasie’s hair.

She knew he had been hurt. Perhaps he would never come back. If he didn’t, that would mean the end for them. Yet she understood Theodora’s sorrow and anger. It was as if Acasius had been wiped out. Removed not only in body but in memory. She had done the only thing she could think of to keep them together, but it had been so sudden that none of them had had time to grieve. Now it seemed that all the tears that they had held in check needed to overflow.

Clinging to each other, the small family of Acasius mourned their loss.