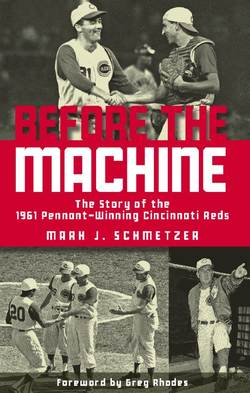

Читать книгу Before the Machine - Mark J. Schmetzer - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

TWO Taking Aim

ОглавлениеConsidering the concealed weapon charge Frank Robinson still was dealing with when he arrived in Tampa, Florida, for spring training in 1961, some people might have found it a bit ironic that the sound of gunfire was common around the Cincinnati camp.

Nobody was particularly alarmed, however, for two reasons—it was expected, and the guns shot only BBs.

They were part of an exercise designed by a Columbus, Georgia, company known as Unlimited Enterprises to improve the players’ focus. A brainstorm of ever-innovative owner Powel Crosley Jr., the idea was for the players to shoot BBs at targets tossed into the air. The targets got progressively smaller and smaller, from baseballs to discs to pennies, all the way down to BBs, which meant the shooter was trying to hit a BB with a BB. The instructors—Lucky McDaniel, Mike Jennings, and John Hughes—eventually would tell shooters to “look at the shiny side of the BB.”

Reds players shoot at the sky during spring training.

Outfielder Wally Post hit six consecutive discs in one stretch before knocking out a wad of paper stuffed into the middle of the disc on his seventh shot.

“It was eye-hand coordination stuff,” pitcher Jim O’Toole said.

“The object of all this is for the boys to correlate their attempts to hit my targets with their attempts to hit baseballs,” Hughes said. “I’m trying to get the players to concentrate on their target, whether it’s a baseball or disc. I have the boys shoot with both eyes open, and I teach them that they should think of the gun or bat as merely a working member of their body.”

Shooting BBs at BBs actually had been implemented by Crosley a couple of years earlier.

“My best year was 1959, and that was the year we had a week of this shooting in spring training,” outfielder Vada Pinson recalled. “Last year I bought a little gun and worked out myself, but that’s not as good as when you have someone helping you. These drills teach you to concentrate, and they help you to pick up the ball faster. Learning to do those things isn’t going to hurt any batter.”

Pitcher Bob Purkey was convinced the drills also helped the mound staff.

“Sometimes a pitcher gets out there and just throws without concentrating completely on his target,” Purkey admitted. “I’ve done it. These drills help me concentrate. You can’t hit the spots if you aren’t concentrating. That’s the difference between a thrower and a pitcher—concentration.”

“They got us down to where he would throw a BB in the air and we could hit it,” young pitcher Jim Maloney said. “We’d started with big washers, bigger than a silver dollar, ten feet in front of you. Within two to three weeks, we were doing that every day. It broke up the monotony of just standing around shagging balls.

“We went from hitting a washer to hitting a piece of paper inside of a washer. Then we got it down to three feet in front you.”

Shooting at BBs was just one of several unusual methods tried by the Reds in their efforts to get the franchise turned around. When the pitchers and catchers reported on February 22 to Plant Field at Tampa for the team’s twenty-eighth spring training in the city, most of them—if not all—had little idea of what was waiting for them.

One new person on hand to greet them was Otis Douglas, a coach described as a physical conditioning consultant. The fifty-year-old Douglas was a fascinating character, sort of a Renaissance man of sports.

The Reedville, Virginia, native, who owned with his wife, Eleanor, a 3,300-acre pheasant preserve in Hague, Virginia, lettered and served as team captain in football and track while earning Bachelor of Science, Master of Arts, and Doctorate of Education degrees at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia. He taught physical education, directed intramural athletics, worked as an assistant football and track coach and as head swimming coach while also serving as head athletic trainer for all of the Indian teams before moving on to the University of Akron in 1939 as assistant and then head football coach.

Besides teaching physical education Douglas also coached wrestling, swimming, track, gymnastics, and freshman basketball and again served as athletic trainer before being named Akron’s athletic director in 1941.

Douglas served as an officer in the Naval Aviation Physical Fitness Program from 1943 to 1945 and was player-coach with the Jacksonville, Florida, Naval Air Station football team in 1945. After the war, he embarked on a professional football career as a player and trainer with the Philadelphia Eagles while coaching football at Drexel Tech at the same time before landing the job as head coach at the University of Arkansas, which he gave up for a job as an assistant with the Baltimore Colts. From there, he spent a year as an assistant at Villanova and another on the staff of the NFL Chicago Cardinals before going north to be head coach of the Calgary Stampeders of the Canadian Football League.

After a year of scouting talent for the Minnesota Vikings in 1960, Douglas joined the Reds.

“He put the Reds through a sprightly course of calisthenics designed to stretch shoulder-girdle muscles, loosen hamstrings and strengthen ankle and knee joints,” Sports Illustrated reported. “The Reds, a bit wary of all this exercise, finally were won over by the diffident but appealing personality of Mr.—or Dr.—Douglas and went into the regular season as well-conditioned a baseball team as there was in either league.”

Frank Robinson, who’d had problems with his throwing arm since 1954, overcame them with Douglas’s help. Robinson’s arm was so bad that he spent most of the 1959 and 1960 seasons at first base, though he was an outfielder by trade.

“Douglas had been hired by the Reds to get the ballclub in condition, and he did just that, though he nearly killed us in the process,” Robinson recalled in his autobiography. “He had us doing pushups and situps and all sorts of impossible exercises that baseball players are never supposed to do. He had us out there until our tongues were hanging out and we were screaming for mercy. But then he would come around and work on my arm, and that made up for all his tortures. He had real strong hands and he was able to massage my arm and dig down deep and break up the knots that always formed in the arm, and he got it in good shape.”

Not right away, though. Robinson missed some time in spring training because of his arm, exasperating manager Fred Hutchinson, who had no room for Robinson at first base with Gordy Coleman ready to take over.

“He’s had enough trouble with that arm to know by now how to take care of it,” Hutchinson growled to reporters, pointing out that Robinson consistently unleashed long throws from the outfield instead of hitting cutoff men and, in the view of the manager, didn’t warm up properly. “Damn it, I want his arm ready to go for the season. If Robinson isn’t ready to play the outfield, he’ll sit on the bench until he is—and he’ll take a [pay] cut.”

Douglas, who also possessed a commercial pilot’s license, was one of three newcomers to Hutchinson’s coaching staff. Antioch, Tennessee, native Jim Turner, who’d pitched on Cincinnati’s 1940 World Series-championship team and spent eleven seasons as pitching coach for the Yankees, returned to the majors as the Reds pitching coach after spending the 1960 season as general manager and manager of the Class A minor league team at Nashville. Turner, known as “The Colonel,” replaced Cot Deal as the Reds’ pitching coach.

Another newcomer was hitting coach Dick Sisler, an outfielder in his playing days who was most famous for the tenth-inning home run he hit off of Brooklyn’s Don Newcombe in the last regular-season game of the 1950 season to help the Philadelphia Phillies—the “Whiz Kids”—clinch their first National League championship since 1915 and their last until 1980. Sisler had spent three seasons as Nashville’s manager before taking Hutchinson’s old job as manager at Seattle in 1960. Sisler replaced Wally Moses as the Reds hitting coach.

Also missing from the previous season’s staff was Whitey Lockman. The only holdover coach was Cuba native Reggie Otero, who was helpful in communicating with Latin American players such as infielders Elio Chacon and Leo Cardenas.

Visa problems, which hamper players and coaches trying to get to baseball training camps from outside of the country, teamed up with airline labor issues to keep Otero and several players from reporting on time, but the other coaches had no problems getting there and gleefully participating in Hutchinson’s ambitious workout schedule. The schedule for February 28, the first day the entire squad was due, called for the players to workout from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m., with a half-hour lunch break.

“Fred Hutchinson had his Redlegs sweating this spring,” Sports Illustrated observed. “They ran, did push-ups, ran some more, worked on fundamentals, did more running and even went to night school. Hutchinson’s reasoning was simple. The Reds last year were a dead team. They finished sixth—comfortably. If they finish sixth again this season, as far as Hutchinson is concerned, they will do it uncomfortably.

“The running that took place at the end of each practice was enough to drop a tough Marine. In spring training running usually consists of a friendly jog of perhaps 50 yards across the outfield, then a leisurely walk back over the same course. Generally, the players are left to themselves: they decide when they have run enough. But at Tampa Jim Turner, the old Yankee pitching coach, stood beside the outfield fence, a counting device in his hand, his cool blue eyes surveying the drooping athletes. When some of them cut the length of the course from, say, 50 yards to 30, old Jim told them to stretch it out again. When one of them insisted that the 20 laps he was supposed to run had been completed, old Jim just smiled and said that his indicator had registered only 17. When the running was finally over and the exhausted athletes walked to the clubhouse 100 yards away, they looked as if they would never make it.”

“Yeah, I’d say things are a little different this spring,” O’Toole told reporters.

On several days, the work didn’t end with the end of the workouts. Fundamentals such as hitting cutoff men also were primary focuses of several night classes convened by Hutchinson in Cincinnati’s 1961 spring training. They were mostly closed to the media, except for one newspaper photo showing the skipper operating a film projector. He also diagrammed on a blackboard the proper ways to execute rundowns and pickoff plays and which players should be backing up which bases in different situations.

Fred Hutchinson puts his players through rigorous exercise during spring training.

The camp looked more like one Vince Lombardi might have run for the NFL Green Bay Packers than a baseball camp. The only things missing were helmets, shoulder pads, footballs, and tackling dummies.

“Hutch was a good teacher,” O’Toole recalled. “The night classes were game situation fundamentals—don’t miss the cutoff man—that could lose a ballgame. Actually, it seemed like there was always some innovation.”

If nothing else, the innovative approaches and increased focus on conditioning and fundamentals broke up the usual monotony and stirred some excitement in the Cincinnati camp. The off-season deals had left many of the players unsure about what to expect when they showed up at aging Plant Field, which had been built by Henry B. Plant in 1899 as an area to provide activities for guests staying at his Tampa Bay Hotel. The Reds worked out at Plant Field before moving to Al Lopez Field for Grapefruit League exhibition games, clearing the way for Cincinnati’s minor league teams to start their camps.

“For a minute, I thought I had the wrong camp,” outfielder Gus Bell said shortly after arriving for spring training. “There sure are a whole lot of fellows here I don’t know.”

“When we went to spring training, you would wait to see who’s coming through the door,” Maloney said.

Several players expected the faces to change as camp progressed. Going into camp, general manager Bill DeWitt believed Hutchinson’s biggest challenge would be developing a second base combination out of the mix of Cardenas, Chacon, Eddie Kasko, and Jim Baumer. Cardenas, twenty-two by then, was generally regarded as an outstanding defensive shortstop, but he’d hit just .232 in forty-eight games with the Reds in 1960 after being called up from Jersey City of the International League on July 24. Cardenas replaced Chacon, twenty-four, who’d made the Reds out of spring training in 1960, but he hit just .181 in forty-nine games before being sent to Jersey City.

The twenty-eight-year-old Kasko had been named the Reds Most Valuable Player in 1960 after hitting .292 while playing mostly third base, which automatically became Gene Freese’s spot after DeWitt acquired him from the Chicago White Sox in a December trade.

Kasko, who played with Freese for St. Louis in 1958, also was a possibility at second base, though the favorite going into camp was Baumer, a former prospect who’d broken into the major leagues at the age of eighteen with the White Sox in 1949. He appeared in eight games with Chicago that year and then didn’t return to the majors until 1961 at the age of thirty.

Baumer had been picked by the Reds out of the Pittsburgh system in the 1960 Rule 5 draft after hitting .293 at Salt Lake City the previous season. Salt Lake City general manager Eddie Leishman was on record as believing the right-handed-hitting Oklahoman could hit .260 and drive in runs at the major league level.

“I think I can do better than that,” Baumer said.

“He’ll have to play his way off this ballclub,” DeWitt said.

Catcher Hal Bevan, who played for Seattle against Baumer in the Pacific Coast League in 1960, also respected Baumer’s potential.

“He’s one of the most consistent players I’ve ever seen,” said Bevan, a PCL All-Star in 1960. “He does a good job every day.”

Others were less impressed. Rumors of trades swirled around camp the entire spring. One had relief pitcher Jim Brosnan being dealt to San Francisco for his former Cardinals teammate, second baseman Don Blasingame. Well-traveled relief pitcher Bill Henry fully expected to not open the season with Cincinnati.

“I thought sure I would be traded during the winter,” said Henry, who believed he’d fallen behind left-hander Marshall Bridges in the bullpen pecking order. “In fact, I began getting the feeling last summer. If you’ll remember, I wasn’t used much after the All-Star Game. I was going badly, and the other fellow got a chance and made good.”

Bridges, a drawling Mississippian from Jackson known as “Fox” and “Sheriff,” had gone 4–0 with a 1.07 ERA in fourteen games after being picked by the Reds from St. Louis on waivers in August, but Henry still possessed a crackling fastball that made him too valuable to give up—at least, for the time being.

Bevan was among a corps of inexperienced candidates to back up incumbent Ed Bailey behind the plate. Though thirty years old, he had a total of twenty-one games of major-league experience, none since appearing in three games for Kansas City in 1955.

The other choices were John Edwards, a Columbus, Ohio, native and Ohio State University student, and twenty-six-year-old Jerry Zimmerman, a former Boston prospect who’d been signed by the Reds as a free agent in September 1959. Neither player had appeared in a major league game. Edwards, a chemical engineering student, reported late because he was finishing the semester.

The rest of the regulars seemed to be fairly settled. Coleman, who won the Southern Association Triple Crown with Mobile in 1959, looked ready for full-time duty at first base after hitting .324 in ninety-three games with Seattle and .271 with six home runs and thirty-two RBI in sixty-six games with the Reds in 1960. He might’ve opened the 1960 season with the Reds if he hadn’t struggled through a miserable spring training.

“There’s sure a big difference in him this spring,” Hutchinson said about Coleman. “He’s relaxed—not all tensed up.”

Dick Sisler, who managed Coleman at Seattle in 1960, believed that the raves from winning the Triple Crown undermined the big, affable first baseman.

“He tried to justify all of the publicity he got, and the pressure got to him,” Sisler said.

Pinson and Robinson were destined to hold down two of the three outfield spots, with Bell and Post battling for right field after combining to hit thirty-one home runs in 1960.

Also in the outfield mix was Jerry Lynch, though it was more likely that he would resume the role of primary pinch-hitter for which he’d already become famous. The left-handed batter, known for his aggressive approach, set the National League’s single-season record for pinch-hit appearances with seventy-six in 1960—beating the record of seventy-five set by Sam “Sambo” Leslie for the New York Giants in 1932—and turned in nineteen hits, three short of Leslie’s record. Lynch also drew eight walks.

Other than the middle infield situation, Hutchinson focused on the pitching, especially the rotation. Purkey, invariably described by sportswriters as “the handsome changeup artist,” had led the team with seventeen wins and a .607 winning percentage in 1960 despite possessing less-than-overpowering stuff. The Pittsburgh native had good size and could occasionally uncork a fastball with some speed on it, but he depended more on style than on substance. He also liked to mix in knuckleballs, which would make his fastball look even more imposing.

O’Toole was coming off a 12–12 season in just his second year in the majors and third in professional baseball. He had won six of his last ten decisions after getting married on July 2, still making his scheduled start on July 3 at Chicago, which he lost, falling to 6–8.

The newly acquired Jay, because of his potential and what the Reds gave up to get him, was penciled in for a third starting slot, but after him, the competition was wide open.

One frontrunner was the immensely talented Maloney, who wouldn’t turn twenty-one until June 2. Maloney had been called up to the Reds during a massive reshuffling toward the end of July in 1960. He made the jump from Double-A Nashville, where he’d gone 14–5 and been picked to play in the all-star game, an appearance he couldn’t make because, by then, he was with the Reds.

Almost simultaneously, Coleman was brought in from Triple-A Seattle, where he’d put together an all-star half-season, and Cardenas was called up from Triple-A Jersey City.

Maloney suffered through the expected growing pains, going 2–6 with a 4.64 ERA in eleven games, ten of them starts. Still, he showed signs of the dominant pitcher everybody expected him to become. One was his 5–0 complete-game win over Philadelphia on September 24.

“Altogether, six guys got called up to get their feet wet in the middle of the 1960 season,” Maloney recalled. “I just knew that I’d gotten a taste of the big leagues and had a chance to stay on the team going to spring training.”

Maloney may have been the most famous of the youngsters. He’d been a hotly pursued prospect after an outstanding career at Fresno High School, where he hit .310, .340, and .500 in his last three seasons and .485 in an American Legion tournament, in which he was named the outstanding player, while playing for Fresno Post No. 4 in 1957. There were as many teams that wanted him to play shortstop as wanted him to pitch, even after he put together a stretch of nineteen consecutive no-hit innings for Fresno City College.

Maloney often has been described as a “bonus baby,” but he wasn’t one in the traditional sense—a group that includes Joey Jay and Dodgers left-hander Sandy Koufax. Teams that signed these prospects for significant bonus money were forced to keep them on their major-league rosters for at least two seasons. The idea was to prevent teams with higher economic resources from throwing tons of money at all of the best prospects and then burying them in the minor leagues while keeping teams with less money from getting a chance to acquire them.

“I signed for a bonus,” Maloney said. “When Koufax signed, if you got more than a certain amount, you had to be on a major-league roster for two years. They did away with that by the time I signed. A bunch of teams were after me to sign. The Reds worked me out in 1958 at Seals Stadium (the first home of the Giants when they moved from New York to San Francisco).

“The night I graduated from high school, I could’ve signed with several teams for anywhere from $30,000 to $60,000. I also had a scholarship to [the University of] California. My dad, Earl, was sort of my agent.

The team had high hopes for talented young Jim Maloney.

“Baltimore flew me out to Kansas City. Paul Richards was the general manger. I could’ve signed as an infielder or a pitcher. Baltimore offered $30,000, but it broke in the papers that they offered $150,000, and my dad didn’t like that. The Reds flew me from Kansas City to Crosley Field for a workout.

“We didn’t have much money, so we were asking $75,000 to $100,000. We didn’t get it, so I went back to school at Fresno City College, but I didn’t like it. There was all kinds of ruckus in the fraternity house, and I felt like a fish out of water. One day, we got a phone call from Gabe Paul and [scout] Bobby Mattick, trying to sign me. They offered me a major league contract. There was a minimum salary of $7,000, but they were going to guarantee me $10,000 for three years and a $50,000 bonus, so that was $80,000 guaranteed. I signed on April Fool’s Day [1959], flew all the way to Tampa and finished up spring training there.”

Maloney was assigned to Topeka, Kansas, of the Class B Three-I League, where the manager was Johnny Vander Meer—who, of course, had authored a memorable string of consecutive no-hit innings of his own back in 1938, when he pitched no-hitters in back-to-back starts for the Reds. Maloney moved up to Nashville the next year, where he came under the tutelage of Jim Turner.

“I got things turned around there—got off to a fast start and never looked back,” Maloney recalled. “After I got called up to the Reds, I started to feel like I could play at that level, so I felt pretty good when I went home for that winter.”

“Maloney doesn’t necessarily have the inside track, but you’d like to see a kid like him win it,” was the manager’s assessment at the time. “I’ll be satisfied if Jim wins ten or twelve for us. Sure, he has a lot of ability, but the major leagues are tough, and there’s no substitute for experience. Jimmy will make it big eventually, I’m sure, but he has a lot to learn.”

While Maloney was a frontrunner for a starting job, by no means was he a lock. Left-hander Claude Osteen, a local favorite from the small town of Reading, Ohio, located just north of Cincinnati, also was one of those 1960 late-July callups. Osteen was only seventeen when he made his major league debut with the Reds on July 6, 1957, but he made just three appearances that season and two in 1959 before going 0–1 with a 5.03 ERA in twenty games, including three starts, in 1960.

Also in the mix was right-hander Jay Hook, for whom time was running out. Baseball had been waiting for years as Hook decided which course he wanted his life to take. Pitching was one option, especially after the Waukegan, Illinois, native signed on August 17, 1957, for one of the largest bonuses ever paid to a pitcher. Hook, in fact, was among the traditional bonus babies from that era. He joined the Reds on September 2 and made his second big league start on September 29 and pitched five hitless innings in Milwaukee against a Braves team that would go on to win the World Series.

Hook teased the Reds with occasional performances of that caliber over the next three seasons, just enough to keep the franchise hopeful of seeing its investment pay off, but he also seemed distracted by his other option. A very intelligent man out of Northwestern University, Hook graduated in 1959 with a Bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering. He would earn a Master’s degree in thermodynamics in 1964, prompting him to retire from baseball and take a job with Chrysler.

Hook’s career conflict didn’t go unnoticed by his teammates.

“What do you think of the academic quality of the Engineering School at the University of Cincinnati?” he asked relief pitcher Jim Brosnan, a conversation recounted in Pennant Race, Brosnan’s diary of the 1961 season. Hook and Brosnan were aboard the team bus in St. Louis on their way to Hook’s first start of the season.

“I no more knew the answer to that question than a girl hop-scotch player would know how to handle Warren Spahn’s curve, so I paused, pseudo-sagely, and said, ‘One of the best in the country.’

“Hook nodded, saying, ‘I’ve got to start a lab project somewhere. My whole summer is just about wasted, don’t you see? Research-wise, that is.’

“‘Sorry baseball’s interfering with your career,’ I mumbled.

“’How about researching twenty-seven hitters for tonight’s game,’ I thought to ask, but held my tongue, foregoing such mundane matters. Maybe Hook relaxes before a game by planning his future.”

Barely on the Reds’ radar going into spring training was Ken Hunt, a big right-hander from Ogden, Utah, who had struck out twenty-one batters in one game, averaging two per inning, and thrown two no-hitters in high school. He also was an all-state basketball player and attended Brigham Young University before signing with the Reds in 1958. He went a combined 5–16 in his first two seasons before finding the key in 1960 with Columbia, South Carolina, of the Class A South Atlantic League, also known as the Sally League. Hunt helped Columbia to the regular-season championship while leading the league with sixteen wins, a .727 winning percentage, and 221 strikeouts. He was the only unanimous pick for the league’s post-season all-star team and was named by the National Association of Baseball Writers as the pitcher on the all-star team for all Class A-level leagues. That performance earned an invitation as a non-roster player to Cincinnati’s spring training camp.