Читать книгу Before the Machine - Mark J. Schmetzer - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ONE Makeover

ОглавлениеBy the end of the 1960 season, the only person who’d been involved with the Cincinnati franchise longer than Gabe Paul was the owner, Powel Crosley Jr., but only by a couple of years.

Crosley had purchased the Reds in 1934 at the urging of flamboyant general manager Larry MacPhail. When MacPhail left in 1936 to take over the Brooklyn Dodgers, Crosley replaced him with Warren C. Giles, business manager of the Rochester Red Wings of the Triple-A International League. Giles brought Paul with him from New York.

Paul was only in his mid-twenties, but he already had a decade’s worth of education in how to run a baseball team. He started as a Red Wings batboy at the age of ten. Six years later, he was helping cover the team for a Rochester newspaper as well as for The Sporting News, already highly regarded as “The Bible of Baseball.” Paul was eighteen years old in 1928 when Giles named him the team’s publicity director and twenty-four in 1934 when he was promoted to road secretary.

Paul took over as Cincinnati’s publicity director when he and Giles moved from Rochester. After serving in the Army during World War II, he returned to his familiar role and remained in it until 1951, when Giles became National League president and Paul was promoted to general manager.

The Reds were unable to win a championship during Paul’s ten years as general manager. In fact, they managed just two winning seasons—1956, when they finished third with a 91–63 record and 1957, when they went 80–74 and finished fourth.

Paul was named Major League Executive of the Year in 1956, the season in which the Reds reached seven figures in attendance for the first time in franchise history, but his record in trades as general manager was mixed. His best acquisition was outfielder Gus Bell from the Pittsburgh Pirates for three toss-away players shortly after the 1952 season. Bell became one of Cincinnati’s most consistent and popular players throughout the decade.

Paul also traded for pitchers Bob Purkey and Jim Brosnan and infielder Eddie Kasko, all solid performers through the late 1950s, and the club signed prospects such as outfielders Frank Robinson and Vada Pinson and pitchers Jim O’Toole, Jim Maloney, and Ken Hunt. Purkey won seventeen games in two of his first three seasons with the Reds, 1958 and 1960, while Kasko was named the team’s Most Valuable Player in 1960 and Brosnan established himself as a dependable relief pitcher.

Robinson burst onto the scene in 1956, tying what was the National League record for home runs by a rookie with thirty-eight while turning twenty-one years old during the season. Pinson, who was three years behind Robinson at McClymonds High School in Oakland, California, showed signs of stardom after being called up for good in 1959, but the pitching prospects still were developing as the 1960s approached.

Paul, after going through seven managers in his first eight and a half seasons, finally found his man in Fred Hutchinson, who replaced Mayo Smith during the All-Star break in 1959.

Other Paul deals didn’t work out as well. He traded power-hitting outfielder Wally Post, another player popular with fans, to the Philadelphia Phillies for left-handed pitcher Harvey Haddix after the 1957 season. Haddix spent just one season with the Reds, going 8–7, before being dealt to Pittsburgh with catcher and pinch-hitting specialist Smokey Burgess and fiery power-hitting third baseman Don Hoak for pitcher Whammy Douglas, utility player Jim Pendleton, and outfielders John Powers and Frank Thomas. None of the new Reds spent more than a year with the team, and Douglas didn’t even play a game for Cincinnati, while Haddix, Hoak, and Burgess all contributed to the Pirates’ 1960 World Series-championship season.

Thomas’s biggest contribution to the Reds was being part of the package sent to the Chicago Cubs on December 6, 1959, in a trade that brought left-handed relief pitcher Bill Henry to Cincinnati.

Paul’s contributions to the 1961 Reds are undeniable, but they had yet to yield anything by the end of the 1960 season, when he was pondering his own change of scenery. The owners of the fledgling Houston franchise, which was scheduled to start play in 1962, were looking for an experienced baseball man to run their operation. Paul, with his experience in several different areas, was an attractive candidate, and when the Colt 45s—later to be called the Astros—approached him during the 1960 season, he was more than intrigued. He announced his decision to leave Cincinnati for Texas on Monday, October 25.

“I met with the Houston people one week ago today, and I had no intention of taking the job,” Paul told reporters. “As the day wore on, I changed my mind.”

Paul made his decision while the aging Crosley, who turned seventy-four on September 18, was hospitalized in Savannah, Georgia. Giles, who had moved the National League offices to Cincinnati’s Carew Tower after taking over as president in 1951, helped with the search for a new general manager. It quickly led to Detroit, where another lifelong baseball man named Bill DeWitt was looking for a way out of his job as president and general manager of the Tigers.

William Orville DeWitt Sr.’s baseball roots ran even deeper than Gabe Paul’s. He started in 1916, at the age of thirteen, selling soda at St. Louis ballgames before becoming an office boy in the front office of the American League Browns, where he started learning the business from Branch Rickey.

Rickey, who is to baseball what Paul Brown is to football, practically invented many aspects of the game now taken for granted, everything from the framework of the farm system to batting helmets. He is most famous, of course, for tearing down baseball’s color barrier with the signing of Jackie Robinson.

When Rickey moved from the Browns to the Cardinals in 1917, DeWitt followed. While working for the Cardinals, he went to night school to study shorthand and typing, which led to being named Rickey’s secretary. DeWitt would go on to fill several jobs in the organization—ticket seller, ticket taker, scoreboard operator, concessionaire—and he handled the tickets for St. Louis’s first appearance in the World Series in 1926. At the same time, he was attending St. Louis University, Washington University, and St. Louis University Law School, all at night, and he eventually passed the Missouri bar examination in June 1931.

DeWitt eventually rose to the role of team treasurer before being named in 1936 an assistant vice president specializing in procuring players for the major- and minor-league teams, which allowed him to indulge his eye for talent. He spent less than a year in that job before returning to the perennially woebegone Browns as vice president and general manager in 1936, and in 1944 he put together the only team to win an American League championship while the franchise was located in St. Louis. The Browns lost to the Cardinals in a six-game World Series, but The Sporting News recognized DeWitt’s accomplishment by naming him Major League Executive of the Year.

The Browns couldn’t maintain the momentum of the mid-1940s and struggled in the shadow of the more successful Cardinals, who appeared in nine World Series and won six in the twenty-one-year span from 1926 through 1946 while sharing Sportsman’s Park with their American League counterparts. DeWitt displayed his taste for dramatic deals in November 1947 when he traded outfielder Vern Stephens and pitcher Jack Kramer to the Boston Red Sox for nine players and $310,000. The deal couldn’t lift the Browns out of the second division, which didn’t keep DeWitt and his brother, Charlie, who was working as the team’s traveling secretary, from scraping together enough money to purchase controlling interest in the Browns in 1949. The DeWitts sold the franchise in 1951 to a group led by the flamboyant Bill Veeck, but Bill DeWitt stayed in the front office until Veeck was forced to sell the team, which was moved to Baltimore and became the Orioles for the 1954 season.

DeWitt landed in New York as assistant general manager of the Yankees for two years before taking over administration of a fund designed to help needy minor league teams in 1956. He spent four years in that job, but he never lost the urge to run a ballclub and put together a contender, so when a group of investors who admittedly knew little about baseball bought the Detroit Tigers, they turned operation of the franchise over to DeWitt.

He wasted little time indulging his own flair for flamboyance while trying to improve a team that finished two games under .500 and in fourth place in the AL. Early in the 1960 season, he pried first baseman Norm Cash from the Chicago White Sox for little-used infielder Steve Demeter. Cash would win the 1961 AL batting championship and spend fifteen years with the Tigers, playing a key role in their 1968 World Series championship.

Five days after acquiring Cash, DeWitt and the even more flamboyant Frank Lane, general manager of the Cleveland Indians, hatched an eye-popping trade in which 1959 batting champion Harvey Kuenn went to the Indians for 1959 home run champion Rocky Colavito. Lane and DeWitt later collaborated in August on the only trade of managers in major league history, with Detroit skipper Jimmy Dykes taking over for Joe Gordon in Cleveland.

The deals made headlines, but did little to improve the teams. DeWitt’s Detroit team lost five more games in 1960 than it had in 1959, and his employment circumstances had gone similarly downhill, recalled his son, William O. DeWitt Jr.

“He was in Detroit, and he’d gone up there as president, general manager, chief executive officer,” said DeWitt, who followed his father into baseball and retraced the family’s roots back to St. Louis as chairman of the board and general partner of the Cardinals. “A group had bought the team, and they didn’t have any baseball background. They wanted a baseball man. They said, ‘You’ll have ultimate authority to run the business.’ Then, after the first year, John Fetzer bought the other guys out and became the controlling partner. He said to my father, ‘I still want you to be the GM, but I’m going to run the team and oversee everything.’ My father said, ‘I understand, but if I get another opportunity, I’m going to take it, because that’s what I signed up for.’”

The younger DeWitt, who turned twenty in the summer of 1961, was a student at Yale University at the time. He recalls his father being approached by Cincinnati banker Tom Conroy, who was secretary and treasurer of the Reds.

“He knew my father,” DeWitt Jr. said. “I can’t tell you the background, but when Gabe Paul left, I think he suggested to Powel Crosley that my father could be available and if so, that he should be the guy who should come and replace Gabe Paul.”

Giles, who had known DeWitt since the two first met in Rickey’s office in St. Louis in 1920, had the same recommendation. At least two other men were rumored to be interested in the job—Cedric Tallis, general manager of the minor league team in Seattle, and Dewey Soriano, president of the Pacific Coast League in which Seattle played—and Giles and Crosley spent two days discussing the situation. In the end, Crosley liked DeWitt’s extensive major league experience.

“We discussed the job,” Crosley told reporters on November 2. “I didn’t make up my mind until this morning. I feel that DeWitt is the most qualified man for the job.”

Despite his long career in baseball and his accomplishments, the DeWitt name wasn’t well-known, at least in Cincinnati.

“I had no clue who DeWitt was,” said pitcher Jim O’Toole, who made his off-season home in Cincinnati. “I didn’t realize he was hanging around with Bill Veeck. He’d been around forever, but he was a very intelligent financial genius.”

How shrewd was DeWitt? While he was getting paid by the Reds to be the team’s general manager, he was still getting paid by the Tigers to not work for them.

“None of the owners knew anything about baseball,” DeWitt said at the time. “Fetzer wanted to be president, which he now is, and he used me against Harvey Hansen, who was president. That didn’t help me a lot with Hansen. Making things worse was the fact that the Detroit farm system hadn’t produced anyone worthwhile in seven years. When Fetzer moved in as president, he wanted to put me in cold storage for two years as his assistant, but I had a contract as president rendering me $100,000 in three years. When the call came from Cincinnati last October 25, I settled the remainder of my Detroit contract for 50 percent, so I will be paid $16,666 a year by the Detroit club until November 1, 1962.”

DeWitt stepped into a situation desperate for stability. Crosley’s illness had allowed questions regarding the franchise’s future in Cincinnati to linger. The latest example was a newspaper report a week earlier that Harry Wismer, a flamboyant New York broadcasting entrepreneur who already owned the American Football League New York Titans, was trying to form a syndicate to buy the Reds.

“If we get the club, I’ll keep it in Cincinnati,” Wismer said. “We have learned there is a chance the Reds may be for sale, and we have been working on this for a couple of weeks. I think if Powel Crosley gives us an even break in negotiations, we will wind up with the franchise.”

Wismer dangled the possibility of Cincinnati getting an AFL franchise as a sweetener. Paul had approached Wismer on Crosley’s behalf about Cincinnati getting an AFL franchise.

“Things were pretty well set for the football franchise, but Powel backed out at the last minute,” said Wismer, who knew his promises about keeping the baseball team in Cincinnati would do little to comfort local fans. They easily recalled that New York was supporting two National League teams as few as four years earlier and might like the Reds at least as much as the Mets, who were due to start playing in 1962.

“Why would we want to move out of Cincinnati?” Wismer said. “Cincinnati is a wonderful, rich, aggressive baseball town. All it needs is for some management to put money into the operation, and it will really go places.”

That man, however, was not Wismer. He didn’t have enough money to operate the Titans. The situation grew so dire that making payrolls grew iffy. The other AFL owners, realizing the league needed a successful team in New York, arranged for Wismer to sell the team to a more financially stable owner. The team was renamed the Jets.

Rumors about the impending departure of the Reds to another city were common, according to Jim Ferguson, who shared coverage of the Reds for the Dayton Daily News with sports editor Si Burick. Ferguson even wrote some of the stories based on those rumors.

“It was very much a fear, whether it could really happen or not,” Ferguson said. “The fear was losing a team to New York. Baseball wanted an NL team in New York, and the Reds obviously weren’t a team drawing a lot of people. They weren’t drawing any people, so there were all these rumors. It wasn’t every day, but stories would pop up that somebody in New York wanted to buy the team.

“There were lots of stories in 1959 and 1960—especially 1960—about the Continental League. They were going to form the Continental League, and one of the strongest guys was Bill Shea in New York. That forced expansion, and when the Mets were awarded a franchise, that definitely eased off the situation with the Reds.

“Another factor against the Reds leaving was that Powel Crosley was the owner. Crosley, as a local guy, wasn’t going to let this team leave Cincinnati.”

DeWitt had to put possible changes in ownership on the back burner in favor of working on turning around the fortunes of the team on the field. His first step was to talk with Hutchinson.

“I’m going to call Hutch,” he told reporters. “I want him to come to Cincinnati next week. We’ll sit down and discuss who the club needs to strengthen itself for next year.”

That comment immediately snuffed out any suspicion that DeWitt would bring in another manager—somebody with whom he was more familiar, maybe somebody he’d worked with in the past. That was a practice common among general managers. DeWitt might have been tempted to bring in Luke Sewell, his pennant-winning manager in 1944 with the Browns, but Sewell had already failed in just short of three seasons in Cincinnati. He led the Reds to back-to-back sixth-place finishes in 1950 and 1951 before being fired by Paul with the 1952 team 40–61 and headed for another sixth-place finish.

“It was different in those days,” Ferguson said. “It wasn’t an automatic thing, when you had a new general manager, that you had to have a new manager and farm director. There was less of that in those days. Hutch was pretty well established at that point. He was a very solid baseball guy and a very strong person. That team didn’t have a lot of leaders on the field.”

DeWitt Jr. wasn’t surprised that his father stuck with Hutchinson.

“He had heard good things about Hutch,” DeWitt Jr. said. “I think he wanted to get the lay of the land here, and I know that his view was that Hutch was a good manager and that was one of the good things he’d inherited when he came here. They developed quite a good relationship.”

DeWitt didn’t feel the same way about the players. The previous season’s sixth-place finish made it clear that the combination on hand wasn’t working, especially the pitching, which posted the league’s second-worst team ERA at 4.00. Only seventh-place Chicago’s 4.35 was worse.

Hutchinson, a pitcher in his playing days, believed that the Reds had a core of talented young pitchers who simply needed experience. They included left-handed O’Toole and right-handers Jay Hook, Ken Hunt, and Jim Maloney. O’Toole was twenty-three and had just three seasons of professional experience, two in the majors. Maloney was twenty and had two years of professional experience, including eleven major-league games. Hook was twenty-four and had only one full major-league season and parts of two others under his belt. Hunt was twenty-one and hadn’t even tasted major-league life in three professional seasons.

The Reds infield: Gene Freese, Eddie Kasko, Jim Baumer, and Gordy Coleman.

DeWitt and Hutchinson also agreed that the team’s middle infield needed shoring up. The six-foot, 180-pound Eddie Kasko had been named by members of the Cincinnati chapter of the Baseball Writers Association of America the team’s Most Valuable Player in 1960 while primarily playing third base, but he was a shortstop by trade and didn’t have the power most teams look for in third basemen. The bespectacled former Cardinal, who’d been acquired after the 1958 season, also played some games at second base in 1960, but Billy Martin had been the primary second baseman and had hit just .246 at the age of thirty-two. The Reds sold him to the Braves after the season.

The Reds also had a couple of middle-infield prospects in Cuba native Leo Cardenas and Venezuelan Elio Chacon, but Cardenas was just twenty-one, had played just forty-eight games in the majors, and his defense was unproven. Chacon was twenty-three, but similarly inexperienced.

The biggest job was getting the pitching in shape, and DeWitt knew he wasn’t going to acquire good pitchers without giving up something of value. He also knew that he had at least two dependable shortstops on his team in Kasko and Roy McMillan, a fielding wizard who’d won the first three Gold Gloves at his position after the award was initiated in 1957. The first year’s awards weren’t split between the leagues, meaning McMillan was considered to be the best-fielding shortstop in baseball. Gold Gloves were presented in both leagues starting in 1958, and McMillan won the National League’s in 1958 and 1959, but he never was a good, consistent hitter, and six seasons of playing 150 or more games in each season seemed to be catching up to him. He played in just seventy-nine games in 1959 and 124 in 1960, while turning thirty-one years old.

Meanwhile, Hutchinson had identified a hulking right-hander named Joey Jay as a pitcher who might fit into the Reds plans. The six-foot-four, 228-pound Jay had broken into the major leagues in 1953 at the age of seventeen as a bonus baby with the Milwaukee Braves, who had given him such a large amount of money to sign that rules of the time made it mandatory that he be on the team’s major-league roster—one of that group of players known as “bonus babies.” His first career start, in fact, was a three-hit shutout of Cincinnati in Milwaukee on September 20, 1953, but his biggest claim to fame stemmed from being the first product of Little League baseball to reach the major leagues.

Jay also had pitched well enough to be named the National League Player of the Month for July 1958, when he was 5–2 with a 1.39 ERA, five complete games and two shutouts in seven starts, but the true indication of where he stood in Milwaukee’s pitching plans came in the World Series. He wasn’t even included on the post-season roster.

Jay suffered from joining a staff dominated by accomplished veterans such as left-hander Warren Spahn and right-handers Lew Burdette and Gene Conley, which left few opportunities for a precocious youngster to work. He never made more than nineteen starts in any of his first seven seasons, and he didn’t help himself with constant struggles to keep his weight down, which led to slow starts that helped create a reputation for laziness.

“Jay had good potential, but he’d never done a lot for Milwaukee,” Ferguson said. “He had a tough time cracking their starting rotation. People thought he could be a good pitcher, but he hadn’t done it a lot.”

Jay also suffered from a classic tradeoff. Sure, the large signing bonus was great, but experience is priceless. Few managers are willing to give regular work to an eighteen-year-old kid with no experience. Charlie Grimm, Milwaukee’s manager when Jay joined the Braves, wasn’t any different.

“Charlie Grimm resented me for that reason,” Jay recalled. “Nothing against me personally, but I was taking up a roster spot. It cost me a couple of seasons, because by the time I was able to go to the minors, I’d already lost those first two years.”

Big Joey Jay was a key addition to the Reds.

Hutchinson decided to find out for himself. He launched an under-the-radar investigation, talking to several people about which was the true Joey Jay—the guy he’d heard about or the guy who’d gone 6–3 over the last two months of the season, including 4–1 in the last month of the season.

One person he spoke with was Bob Scheffing, a coach with the Braves in 1960 who’d been named manager of the Tigers.

“He’s always been a slow starter,” Scheffing later told reporters. “If he’s physically sound, you don’t have to worry about him—and if the Reds don’t want him, I’ll gladly take him. He’ll win more games than any other Reds pitcher. I tried to get Jay myself after I signed with the Tigers, but we needed a center fielder more than a pitcher, and after giving up Frank Bolling for Bill Bruton, we didn’t have anything else to offer in a trade.”

“I was told that it was true that Jay goofed off the first half of the season,” Hutchinson said. “The second half, though, he gave a concentrated effort. They told me he reached maturity. He finally reached the point where he believed he was a major leaguer and was willing to work toward it.”

Jay was well aware of his reputation.

“I guess it all dates back to when I was just eighteen,” he said. “In those days, I didn’t know beans about nothing. I ate up a storm during the winter and reported to the Braves training camp weighing 244 pounds. Once you get the reputation for being lazy, it’s hard to shake. During each of the last three springs I spent with Braves, I was told by the manager that I was going to be the fourth starting pitcher, but it never worked out that way. I didn’t pitch much with the Braves, but I couldn’t see where it was my fault. Last spring, I even made a special effort to get off to a good start. I came to camp at 222 pounds, eight less than my usual reporting weight, but it was almost the end of May before I got a chance to pitch, and sitting around during the first weeks of the season isn’t good for any pitcher.”

Another source tapped by Hutchinson was, of all people, Braves pitcher Lew Burdette.

“Hutch asked Lew about the Braves’ young pitchers, and Lew recommended me,” Jay said. “I was very pleased. I knew Cincinnati had a good club—hitters like Frank Robinson and Vada Pinson, pitchers like Purkey, O’Toole, and Brosnan.”

Hutchinson’s case for Jay was strong enough to convince DeWitt to go after the pitcher. The Braves, concerned about the decline of long-time shortstop Johnny Logan—who would be thirty-four going into the 1961 season, his eleventh in the majors—were so interested in McMillan and so confident in their pitching depth that they also were willing to include left-handed pitching prospect Juan Pizarro with Jay in a trade that was completed on December 15, 1960.

“He’s the pitcher I didn’t want to give up,” Milwaukee manager Chuck Dressen said later, referring to Jay.

“Yeah, I can believe that,” Jay responded with a hint of sarcasm. “They even tried to trade me during the season last year.”

“I knew Bill DeWitt was serious when he went out and got Joey,” O’Toole said. “Joey was a big ox out there. He was so nonchalant, we were trying to figure out where he was coming from. He was only twenty-five when he came over here, and he’d already been in the big leagues for seven seasons with Milwaukee. He could do it all out there on the mound. He’d give you eight or nine innings every time out.”

“He’s going to get a chance to perform every fourth or fifth day, and he’s no dummy,” Hutchinson promised. “He knows if he can’t pitch for us, he’ll have to start thinking about the minor leagues.

“A lot of people think we gave up on Roy McMillan. It isn’t so. Joey Jay and Juan Pizarro are a couple of good, young pitchers. The Braves were willing to give them up only for what they wanted, and that was McMillan.”

McMillan, a native of Bonham, Texas, had become so settled in Cincinnati that he purchased a pizza franchise in Hamilton, located about thirty miles north of the city. Still, he wasn’t surprised about being traded.

“When you read in the paper every day that you may be going, you’re not surprised when you go,” he said. “When you hear so many rumors, it’s not just general manager’s talk. I knew it, but I hoped it wouldn’t happen. No baseball player likes to be traded. It’s the toughest thing in the game. It’s worse than a bad year. You get used to the fellows on the ball club and the town and the way of doing things, but I’ve been around in baseball long enough, so I wasn’t surprised. I knew I was going to be traded.

“I’ll tell you something. I didn’t like being traded, but I’m glad I’m with a club that has a chance to win it. Third place is the highest we ever finished in Cincinnati. I sure wouldn’t mind playing in a World Series this year.” He would miss, of course, that opportunity.

Pizarro was only twenty-three, but he also was blocked in Milwaukee’s pitching plans. The Puerto Rican made just ninety appearances, including fifty-one starts, in four seasons with the Braves. Those are averages of twenty-three appearances and thirteen starts. He was 23–19 in those appearances, but by going 6–7 with a 4.55 ERA in twenty-one 1960 games he convinced Milwaukee that he wasn’t going to pan out.

The presence of O’Toole and Henry and the acquisition of Jay made Pizarro expendable, and DeWitt knew exactly what he wanted to do. He had his sights set on Chicago White Sox third baseman Gene Freese, an outgoing twenty-six-year-old native of Wheeling, West Virginia, known as much for defensive lapses as he was for the pop in his right-handed bat. The solidly built Freese had just completed his sixth season in the majors, but Chicago was already his fourth team. He’d hit twenty-three home runs and driven in seventy runs with Philadelphia in 1959, prompting the Phillies to trade him to the White Sox for outfielder Johnny Callison. Freese’s homer output dropped to seventeen, but he drove in seventy-nine runs while hitting .268.

Freese was listed on official rosters at five feet eleven and 175 pounds, but he admitted that his height was an exaggeration.

“I lied on my bubblegum cards,” he said. “I said five-foot-eleven just to make me feel bigger. Other guys lied about their age. I lied about my height.”

Despite that, DeWitt saw Freese as the power-hitting third baseman common to most winning teams, and he knew the Reds had enough pitching depth to tempt the White Sox. Just hours after completing the deal with Milwaukee, he sent Pizarro and a thirty-five-year-old right-hander grandly named Calvin Coolidge Julius Caesar Tuskahoma McLish—who’d gone 4–14 with a 4.16 ERA for Cincinnati in 1960—to the White Sox for Freese.

Ironically, McLish had joined the Reds exactly one year earlier when he was traded with Martin and first baseman Gordy Coleman by Cleveland for second baseman Johnny Temple.

“I knew Chicago was going after pitching help, and by the process of elimination, I figured I’d be the one to go,” said Freese, who was nicknamed “Augie” but liked to refer to his bat and, occasionally, himself as “The Old Destroyer.” “I was the only one they figured they had a replacement for.”

He also knew that his defense was the butt of jokes. Sometimes, he made them himself.

“They don’t make jokes when I’m swinging ‘The Old Destroyer,’” he pointed out.

Though he didn’t know it yet, with those two bold, decisive moves, DeWitt had added what would become critical pieces of the team that would win the NL championship. He hadn’t answered all of the questions—Hutchinson still had concerns about his second base situation—but DeWitt was confident that he’d shored up the pitching and improved the run production.

Unfortunately for DeWitt—a portly man who wore rimless glasses and whose wide eyes made him look as if he were perpetually startled—the brilliance he displayed in completing the 1961 team will forever be overshadowed by his headline-making trade of Robinson to Baltimore after the 1965 season. In one book about Cincinnati’s baseball history, the Robinson trade was ranked on the list of the ten worst trades in Reds history. The December 15, 1960, deals didn’t make the list of ten best trades, even though it took a lot of courage to trade away a very dependable shortstop who also was one of the team’s most popular players in exchange for two unproven pitchers.

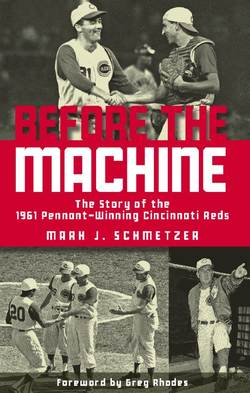

Owner Powel Crosley (left) welcomes Gene Freese (right) to the Reds as Bill DeWitt (center) looks on.

In many ways, the 1960 deals compare favorably with Bob Howsam’s headline-making November 29, 1971, trade of first baseman Lee May, second baseman Tommy Helms, and utility specialist Jimmy Stewart to Houston for second baseman Joe Morgan, pitcher Jack Billingham, outfielders Cesar Geronimo and Ed Armbrister and third baseman Denis Menke—the historic deal that turned the Big Red Machine into eventual World Series champions.

“One thing about him was he did what he thought was right and made the deals that he thought would be successful and didn’t think too much about ‘gosh this guy was a fixture’ and what was the media going to say,” Bill DeWitt Jr. said of his father.

Even a pitcher such as O’Toole didn’t flinch at seeing an accomplished defender traded away.

“DeWitt made some tremendous trades,” O’Toole said. “McMillan was near the end of his career. He was still a great shortstop, but we had some guys in the background that could fill in that spot, and you can never replace good pitching. I wasn’t really that concerned, because there are a lot of guys around who can catch the ball. Eddie Kasko was a perfect example, and we had Cardenas backing him up, so we were fortunate in that regard.”

Maloney, watching developments from his off-season home in Fresno, California, didn’t know what to think.

“I didn’t know too much about Gene Freese,” Maloney recalled. “I’d heard of Joey Jay, and I knew that he was the first Little League player to go to the big leagues. McMillan had been with the Reds quite some time. When I signed with the Reds, he was one of the older guys who sort of took me under his wing—him and Gus Bell. When they traded McMillan, I was sorry to see him go. To me, he was ‘Mr. Shortstop.’ He was a nice guy, but I was just getting my feet wet. I didn’t know a lot about how teams operate. I was just keeping my mouth shut and my eyes open and taking direction.”

In what turned out to be an off-season of quality over quantity, DeWitt would make just a couple more deals before spring training. He sold Martin’s contract to Milwaukee on December 3 and traded left-handed pitcher Joe Nuxhall to the Kansas City Athletics for twenty-seven-year-old right-hander John Briggs and twenty-four-year-old right-hander John Tsitouris.

Nuxhall, a Hamilton native, was best known for being the youngest person to play in a major-league baseball game when he took the Crosley Field mound for the Reds against the Cardinals at the tender age of fifteen on June 10, 1944. He’d made the National League All-Star team in 1955 and 1956, but by the time he turned thirty-two in 1960, he couldn’t stick his head out of the dugout without being greeted by a torrent of boos. Going 1–8 with a 4.42 ERA and letting his explosive temper get the best of him at times didn’t help.

“I asked for it,” Nuxhall recalled. “That particular year, nothing went right. It was a horrible year. I could pitch six shutout innings, and all of a sudden, something would happen. The fans were on me, and I just felt, ‘Well, I want to get out of here. I’ll see if they’ll trade me.’”

A more stable and effective Nuxhall would be back with the Reds in time to go 5–0 with a 2.45 ERA in twelve games, including nine starts, in 1962, and he would go on to finish his career as a player before becoming a much-beloved broadcaster. He would never say he was haunted by the irony that he spent fifteen of his sixteen big-league seasons with the Reds and that they won a championship in the only season he missed, but his disappointment was understandable.

“You don’t know if we would have won if I’d been here,” said Nuxhall, who died in November 2007. “Those things you don’t know. In fact, it was a miracle year, from whatever people tell me about it. They weren’t that great of a ballclub, but everything popped into place, which is really what has to happen in a lot of cases. It just happened to fall that way, and they won the pennant.

“Sure, hell, I would’ve loved to have been here. That’s the dream of any professional athlete—to play for the world’s championship. Like I told some people at a banquet, I don’t care what you’re doing in sports as a team, your ultimate goal is to be in a championship, whether it’s Little League, municipal league, whatever. You say, ‘Well, I’m just playing for fun.’ Basically, I don’t buy that, because you know at the end of the season, somebody has to be the champion, and if you don’t have that feeling, then you’re wasting your time, in a sense. You might as well go jog or something.”

Perhaps DeWitt’s best move of the off-season was one he didn’t make—out of bed in the wee hours of the morning of February 10, 1961. DeWitt was called at his home by Earl Lawson, the Reds beat writer for the Cincinnati Post and Times-Star who’d been tipped off that Frank Robinson had been arrested and charged with carrying a concealed weapon. Lawson told DeWitt that Robinson could be released at 8 a.m. if someone would post $1,000 bail, and the reporter admitted being “a little startled” when DeWitt said, “Well, I guess one of his friends will bail him out.”

Robinson had been arrested following the second of two altercations that night at a Cincinnati diner. He and two friends had stopped for hamburgers after a night of bowling and basketball and gotten into an argument with three youths. The cook called for help from two police officers who were eating in their cruiser. They came in and, while trying to calm the situation, referred to Robinson and his two African-American friends as “boys,” prompting one of Robinson’s friends to grow irate enough that the officers arrested him for disturbing the peace.

After he was bailed out, the three went back to the restaurant to retrieve their food—as did the two police officers. The officers left the restaurant and went back to their car while Robinson and his friends decided to stay and eat at the restaurant. At some point, Robinson looked into the kitchen and saw the cook looking at him and making throat-slitting gestures. That was the last straw for Robinson, who challenged the cook, as he described in his 1968 autobiography, My Life Is Baseball, co-authored with Al Silverman.

“He started toward me, with a butcher’s knife in his right hand,” Robinson recalled, adding that the restaurant layout prevented other diners from seeing the knife. “I saw him all right. He was coming at me with that butcher’s knife poised in his right hand.”

Robinson pulled a .25 Beretta—a small, Italian-made pistol—from his jacket pocket and held it in the palm of his left hand. He’d purchased the gun during spring training a year earlier, primarily because he often carried large amounts of cash and had to walk fifty yards in a dark area from where he parked his car to his Cincinnati apartment.

The cook stopped and yelled, “Hey, that guy’s got a gun,” bringing the officers back inside. Robinson slipped the pistol back into his pocket and lied when asked by one of the officers if he had a gun. They found it after frisking him and arrested him.

Robinson was as surprised as he was disappointed that DeWitt did nothing. Gabe Paul and Birdie Tebbetts had personally rescued Robinson after he became involved in a police matter during spring training in 1958. No charges against Robinson were filed after that incident, and Robinson understandably expected similar help from DeWitt after the later problem—even though the accepted practice at the vast majority of businesses is to leave employees to handle their own personal legal issues. That’s what adults do, and that’s what DeWitt made the twenty-five-year-old Robinson do.

That wasn’t the first time in their short relationship that Robinson had problems with DeWitt. They didn’t personally meet after DeWitt was hired until bumping into each other in the team’s downtown Cincinnati offices.

“When Mr. DeWitt took over the club, I just thought the right thing for him to do would be to at least call up the players, especially the ones who lived in town, and introduce himself, say hello, maybe talk a little with them,” Robinson wrote in his book. “But nothing. I met him by accident one day when I was in the office talking to the switchboard operator. He happened to come out of his office and saw me and introduced himself, the official greeting.”

Relations grew frostier during contract negotiations. DeWitt was a notoriously soft touch for sob stories and down-on-their-luck ex-players, and he gave everybody in the Cincinnati front office a 10 percent raise immediately upon taking over and gave them another one ten months later. But he wanted Robinson to take a pay cut before the 1961 season, while Robinson wanted to be paid at least as much as he earned in 1960.

“He said, ‘I hear you don’t hustle all the time,’” Robinson wrote. “I blew up. I said, ‘Have you ever seen me play?’ He said, ‘No, no not really, not over a full season.’

“Well, until you do, don’t tell me that I don’t always put out on the field. I do.”

DeWitt pointed out that Robinson seemed to play better when he was angry, and that DeWitt planned to keep Robinson angry throughout the upcoming season.

“He was going to keep poking me, keep me at the boiling point, he implied, to get the best performance out of me,” Robinson explained. “I left Mr. Bill DeWitt feeling that I had struck bottom in my career, and that there was only one way to go—up. I was wrong.”

No, that low point was the long night Robinson spent sprawled on the hard bench of a Cincinnati jail cell, with just his jacket for a pillow.

“The most disturbing thought of all, the one that haunted me all night long, was what the kids would think of me,” he wrote. “So many kids idolize big-league ballplayers. So many of them mold their whole lives around their heroes. What were they going to think? How were they going to react?

“And then it began to dawn on me that I had a responsibility to the game of baseball. Baseball had been good to me, and I had taken a lot out of it, but what had I given back? I felt a deep responsibility to baseball, especially to the young kids who look up to the players. I felt that I had let them down.

“For the first time, I began to realize that I wasn’t a kid any more, and that I had better stop acting like one. I knew that I had been wrong, dead wrong, all the way. But looking back, it may have been the best thing that ever happened to me. It matured me, it made me a better man. No, not a better man—a man. Let me put it that way because I don’t think I was a real man before.”

Robinson’s problems that night had started when the police officers called him a boy while he thought he was a man. By the end of the night, he was acting like one.

Not that his troubles were over. As he expected, he heard a great deal in spring training early and often about the incident. It started when he reported to camp and found a water pistol in his locker, left there by teammate Ed Bailey.

“Thanks, Ed, but I can’t use it,” Robinson said, playing along while handing the toy back to Bailey. “I’m on parole.”

When the Reds traveled to Bradenton, Florida, for an exhibition game against Milwaukee, Hank Aaron and Felix Mantilla serenaded Robinson from the Braves’ dugout, singing, “Lay that pistol down, babe, lay that pistol down.” Milwaukee pitcher Lew Burdette snuck up on Robinson and frisked him, reporting to Braves third baseman Eddie Mathews, “It’s all right, Eddie. He’s clean.”

Mathews, who’d gotten into a fight with Robinson the previous season, responded with, “Hey, Robby, I’m not fooling around with you this year.”

St. Louis Cardinals first baseman Bill White called him “John Dillinger.”

“He’ll probably get a lot of that this year,” one Reds player said.

The roster wasn’t the only aspect of Reds baseball that underwent something of a makeover between the 1960 and 1961 seasons. The ballpark itself was brightened up with a paint job, the old green being covered up with a couple of coats of white, while additional space had been found on the massive scoreboard in left-center field for the two new American League teams.

More glaring was the change in the area around Crosley Field, which showed unmistakable signs of the ever-growing dominance of the automobile. For decades, space for parking cars around Crosley had been an afterthought. Most of the fans arrived for games in buses or trolleys or on trains that pulled in a few blocks south of the ballpark at Union Terminal. Most fans could walk back and forth easily, while most of those who drove to the games had to settle for finding parking spots on the narrow, neighborhood streets around the ballpark.

The unexpected success of the 1956 team, and the relative explosion in attendance, forced Reds management to face the fact that more and more fans were going to be driving cars to games and would need safe places to park. The one, 400-spot lot one block south of the ballpark on Dalton Street wasn’t nearly enough. Powel Crosley started talking with city officials about finding a way to add 5,000 spots around the area, and he wasn’t shy about holding the future of the franchise over the city’s head.

“There are so many other cities ready to offer a stadium, adequate parking space, and everything of that sort, practically for nothing,” Crosley said. “In this competitive situation, we are entitled to ask for some additional parking space.”

The Reds, located in one of the smallest markets in major league baseball, always had been a regional team. As the 1950s turned into the 1960s and the development of the interstate highway system made it less time-consuming to drive long distances, license plates from Indiana, Kentucky, and West Virginia became more common sights in parking lots at Reds games.

Eventually, on April 28, 1958, the Reds and the city signed an agreement under which the city agreed to build parking lots and Crosley guaranteed that the franchise would remain in Cincinnati for at least five years.

Beginning in 1959, the city was able to start working out deals with surrounding property owners and clearing lots for parking spaces. Before the 1961 season, one major landmark fell victim to the needs. The Superior Laundry building, located across York Street beyond the left field wall, was demolished. The demolition also meant the loss of the Siebler Suit advertising sign, which guaranteed a new suit for any player who hit the sign with a home run. Reds slugger Wally Post had picked up more than ten Siebler suits through the years, while Willie Mays of the New York/San Francisco Giants had led visiting players with seven.

The team’s official 1961 yearbook includes a page featuring an aerial view of Crosley Field from the south. The word “parking” is stamped over eleven different lots around the ballpark, adding spaces for a total of 6,000 cars, up from 3,500 available in 1960. The city spent just less than $1,200,000 to buy the properties, clear them, and build the lots.

“The city-owned parking lots will all be surfaced and have guard rails of some sort around each lot,” the article reports, adding, “New roads, such as the Dayton Expressway, are making it much easier for Reds fans to get to Crosley Field.”

As added evidence of the automobile’s growing dominance, fans could see, just beyond the center- and right-field walls, the pathway for what eventually would become the Mill Creek Expressway portion of Interstate 75. This was the latest link in the chain of a Hamilton County highway that had been started in 1941 as a four-mile stretch from Hartwell Avenue north to Glendale-Milford Road, which helped make it easier for workers to get to the Wright Aeronautical Plant—later a General Electric facility—in Sharonville, where engines for World War II bombers were being built.

The stop-and-start nature of the interstate system at that time made getting to Reds games much different than it is today. Ferguson recalled the challenges of getting to Crosley from Dayton.

“There were three or four ways to come,” he said. “You could come straight down U.S. 25 right through Miamisburg, or you could take a couple of side roads over to (state route) 741 that ran parallel to 25, east of there. Another way we took was going partway down 25, then swinging west past Middletown over to 747. Eventually, that would hit Spring Grove Avenue when it went way on out.”

By the late 1950s, according to a history of Interstate 75 written by Jake Mecklenborg for “Cincinnati-transit.net,” the highway had advanced south to the Ludlow Viaduct, getting closer to linking up with the Kenton County expressway in Northern Kentucky. The last link was the four-mile stretch from the Ludlow Viaduct to the Ohio River, including construction of the Brent Spence Bridge. Space for the stretch through Cincinnati’s West End and Queensgate neighborhoods still was being cleared in 1961. Eventually, as many as 20,000 people from close to 5,000 families, as well as 551 businesses, would be displaced.

The city cleared out the buildings on York Street, behind Crosley Field, to create additional parking spaces.

Before construction prevented it, the Reds were able to use the cleared area beyond the outfield walls for—you guessed it—parking.