Читать книгу Before the Machine - Mark J. Schmetzer - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

introduction

ОглавлениеAt first glance, the 1961 National League schedule only looks like it was put together by somebody who had no idea of how to do it.

As it turned out, the league couldn’t have done a better job, especially giving the Reds two days off in the middle of the last week of the season. The team—the town, for that matter—needed every one of the forty-eight hours consumed by September 27 and 28 to recover from its biggest party since V-J Day marked the end of World War II sixteen years earlier.

Everybody in Cincinnati had much to celebrate on September 26, 1961, and they had plenty of time to prepare. The pressure to let off the steam had been building like beer in a shaken-up keg. One day earlier, on September 25, the Reds had flown to Chicago to play one game against the Cubs. Cincinnati, picked by most observers before the season to finish sixth in the National League in 1961, owned a four-game lead over the second-place Los Angeles Dodgers with four games left to play. The Dodgers, though, still had six games to play and remained mathematically alive. If they swept their last six games and the Reds lost their last four, Los Angeles would win the pennant. On the other hand, one more Reds’ win and one more Dodgers’ loss would complete what many in Cincinnati and around baseball would consider to be nothing short of a miracle.

It took only the next day the two teams played. The Reds beat the Cubs, 6–3, at Wrigley Field on Frank Robinson’s two-run homer to tie the game in the seventh inning and Jerry Lynch’s two-run homer to give Cincinnati a 5–3 lead in the eighth. Besides coming out of the bullpen to allow one hit with four strikeouts over the final three innings to get the win, relief pitcher Jim Brosnan drove in Robinson with an insurance run in the ninth, and the Reds immediately flew back to Cincinnati.

Meanwhile, the Dodgers had won the first game of a doubleheader in Pittsburgh, 5–3. The second game still was being played as the Reds plane landed at the airport in Northern Kentucky, where Cincinnati mayor Walt Bachrach and a group of fans greeted the returning heroes. More fans lined both sides of much of the bus route to downtown Cincinnati, creating a parade feeling, and an estimated 30,000 gathered at Fountain Square, making it nearly impossible for the team bus to move more than a few inches at a time.

“I’ll never forget that,” said pitcher Jim O’Toole, a Chicago native who had left his wife and their newborn son with family in Chicago. “That was the biggest thrill of my life, to leave the airport and parade down I-75 all the way to Fountain Square. People were rocking the bus—on top of the bus. We were all so excited.”

Everybody was monitoring the second game of the Dodgers-Pirates doubleheader, some with transistor radios. When Los Angeles left fielder Jim Gilliam flied out to Pittsburgh left fielder Bob Skinner at Forbes Field to wrap up an 8–0 Pirates win, the party was officially on. While giddy fans created pandemonium on Fountain Square, the Reds gathered for their own celebration in a room located by manager Fred Hutchinson at the Netherland Hilton hotel.

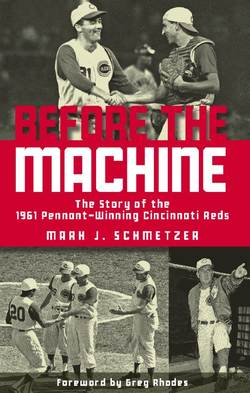

G.M. Bill DeWitt proudly displays a team photo.

“Hutch was up there singing some Frank Sinatra songs,” O’Toole recalled. “The players were having a great time.”

Earl Lawson, who covered the Reds for the Cincinnati Post & Times-Star, remembered the party as a “wing-ding” in his book Cincinnati Seasons—My 34 Years with the Reds.

“‘Earl, how in the hell did we do it,’” Lawson recalled being asked by third baseman Gene Freese upon arrival. “‘We’ve got the worst infield in baseball.’”

“It was a good question. His comment had considerable merit. Freese was a guy who could poke fun at himself.

“Freese stood on the bandstand that night and bellowed, ‘Hutch, I may have bobbled some groundballs, but I never let one get through me.’ Teammates howled as Freese opened his sport coat, revealing a plastic baseball which he had attached to his shirt front.”

Freese was a major reason the Reds were able to rise from the team that finished sixth in 1960 to a champion. The veteran journeyman and second-year first baseman Gordy Coleman turned in virtually identical seasons, each hitting twenty-six home runs and driving in eighty-seven—production that kept opposing teams from pitching around Frank Robinson, helping the outfielder turn in a season that led to him being named the NL’s Most Valuable Player.

Freese was one of several key players acquired in a series of shrewd moves made by first-year general manager William O. DeWitt, who could do almost nothing wrong that year. Virtually every move made by DeWitt, the living, breathing definition of a lifelong baseball man, paid off that year—and for many years down the road.

DeWitt didn’t exactly save the franchise for the city with that season. To say that would be, at best, a stretch. To say, however, that the season put back on track a franchise that had been foundering would be, at worst, defensible. To say that seeing the team confound the so-called experts by winning the championship summed up the times would be an underestimation.

The National League—indeed, Major League Baseball in general—was in a state of upheaval at that time. From that point of view, Cincinnati winning the pennant was almost to be expected.

More unexpected was the impact that season had on the franchise. Starting with that season, which ended with a 93–61 record and .604 winning percentage, the Reds were one of only two teams in Major League Baseball to finish over .500 at least nineteen times in the next twenty-one years. Starting in 1961 and going through 1981, Cincinnati finished below .500 only twice—in 1966 and 1971. Only the Baltimore Orioles match that run. The Orioles also finished under .500 twice—1962 and 1967. The Los Angeles Dodgers come the closest to sustaining that level of consistent excellence, but they finished under .500 four times in that span of time.

Not only was Cincinnati’s franchise back on healthy ground, but the seeds were being planted that would lead to the phenomenally successful 1970s. Infielders Pete Rose, Tony Perez, and Tommy Helms already were in the organization. First baseman Lee May would be signed out of high school that year. Outfielder Bernie Carbo and catcher Johnny Bench would be the team’s top two picks in the first amateur draft in 1965. Right-handed pitcher Gary Nolan would be the last number one pick of the DeWitt era, in 1966.

They all would play roles in making the Reds a dynasty in the 1970s that reminded veteran fans of earlier times—when teams were built for the long haul.

By the end of World War II, no sport at any level could match the popularity of Major League Baseball, a title that was so safe that its proprietors felt no need to slap a trademark on it, so it didn’t need to be capitalized. College football was popular, but there were so many colleges that the fan base was splintered, and the turnover in players was too frequent to allow fans to hold on to any specific star for long-term adoration. Pro football still was more than ten years away from the epic playoff game between the Baltimore Colts and New York Giants that would allow it to grab a share of the national spotlight. Pro basketball didn’t even have a league until 1946 and only became the National Basketball Association when two leagues merged in 1949.

One reason for baseball’s popularity was its easy familiarity. Baseball was in its fifth decade of virtually no changes in its basic framework. As far as at least two generations of Americans were concerned, there always had been two major leagues, American and National, each containing eight teams. The teams always had played in the same cities. Four cities—Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago, and St. Louis—each had two teams, one in each league. New York, of course, had three—two in the National League. Five had to settle for serving as the home of just one team: Cincinnati and Pittsburgh in the National League, the so-called Senior Circuit because it was older than the American League, home of teams in Washington, D.C., Cleveland, and Detroit. All of the teams were located in the northeast quadrant of the country, none of them farther west than the Central Time Zone.

The scarcity of teams made following them easy. Listening to the games on the radio and reading about your team and others in the local newspapers and The Sporting News—the weekly “Bible of Baseball”—gave you a level of information that would make even an Internet junkie jealous.

One man, Maxwell H. Lapides, put it quite well in a comment he made to Roger Angell, the long-time fiction editor for The New Yorker magazine who dabbled in writing about baseball. Angell quoted Lapides in a story about three devoted Detroit Tigers fans called “Three for the Tigers,” which ran in the magazine as well as in a collection of his columns published in 1978 entitled Five Seasons.

“You have to try to remember how much easier it was to keep up with all of the baseball news back then,” Lapides told Angell. “For us, there were just the Tigers and the seven other teams in the American League, so we knew them by heart. All the games were played in the afternoon, and none of the teams was in a time zone more than an hour away from Detroit, so you got just about all the scores when the late-afternoon papers came. You could talk about that at supper, and then there were the stories in the morning papers to read and think about the next day. Why, in those days we knew more about the farms than I know about some of the West Coast teams right now. By the time a Hoot Evers or a Fred Hutchinson was ready to come up from Beaumont, we knew all about him.”

There also was a certain level of comfort in following a particular player. The reserve clause still was in affect, restricting player movement to the whims of owners and general managers or to retirement. Fans who wanted to follow, say, Joe DiMaggio or Ted Williams or Pee Wee Reese could feel much more secure in the knowledge that their favorite player would be with the same team for the bulk—if not all—of his career. Heck, one guy—Cornelius Alexander McGillicuddy, better known as Connie Mack—managed the Philadelphia Athletics for exactly fifty years, from 1901 through 1950.

The continuity was downright impressive, especially when compared to the current state of the game, which can be traced in part to Lou Perini’s decision to move his National League franchise from Boston to Milwaukee for the 1953 season. That opened the floodgates. Franchises started following the post-war migration of the United States population to the west and south. The St. Louis Browns, forever the second team in the Gateway City behind the beloved Cardinals, bucked the trend by moving east to Baltimore after the 1953 season, but the Orioles still thrived. The Athletics left Philadelphia for Kansas City the next year.

The seismic shift came after the 1957 season, when both New York National League teams, the Giants and the Brooklyn Dodgers, made the transcontinental leap to the West Coast. The Dodgers ended up in Los Angeles, while the Giants landed in San Francisco.

Suddenly, almost nothing could be counted on. Fans in other cities had to be wondering which team would be the next to seek greener pastures. Among the more nervous were the fans in Cincinnati.

The Reds by then already had a proud history. They invented the all-professional team back in 1869 and were among the original National League teams in 1876. Their track record wasn’t as glowing as, say, the Giants or Dodgers or Cardinals, but they’d had stretches during which they were regular contenders and could boast of three league championships and two World Series titles.

By the late 1950s, though, the legs of this franchise were shakier than others. The team had enjoyed a sensational season in 1956, cracking home runs at a near-record pace and attracting one million fans to the ballpark for the first time in franchise history. The Reds hit 221 homers, tying what was at the time the major league record. Slugging first baseman Ted Kluszewski and his biceps—so bulging that the sleeves of his uniform jersey constricted them, forcing him to play bare-armed and eventually prompting the Reds to adopt vest-type jerseys—were fan favorites. Frank Robinson, at twenty-one years old, tied a league record for rookies with thirty-eight home runs. Cincinnati contended for the pennant for much of the season before settling for third place with ninety-one wins, snapping at eleven the team’s streak of consecutive losing seasons.

Unfortunately, they couldn’t build on that improvement. Cincinnati slipped to fourth place in 1957, fourth place again and under .500 in 1958—costing manager Birdie Tebbetts his job—and fifth place in 1959, which included the dismissal of Mayo Smith as manager after just a half-season. Picked to replace Smith was Fred Hutchinson, the former Detroit pitcher who’d previously managed the Tigers and Cardinals with no notable success. Hutchinson was thirty-nine years old when he took over the Reds.

“The franchise had been under .500 seemingly forever, except for 1956 and 1957,” recalled Jim Ferguson, who helped cover the Reds for the Dayton Daily News from 1959 through 1972 before becoming the team’s publicity director. “They were a pure power team, but they had terrible pitching. They couldn’t score enough runs to win. They hadn’t had any success, with the exception of those two seasons, for a couple of decades.”

The managerial changes did little to calm the nerves of Reds fans. Cincinnati’s home ballpark, Crosley Field, was the smallest in the league in terms of seating and offered little room for parking, a growing problem in a society that was spending more and more time behind the wheel. Folks didn’t take trains or buses or trolleys to ballgames any more. They drove, and they were more inclined to visit places where they figured they could safely leave their cars.

The Reds needed only to look over their right field fence to see the future. A stretch of Interstate 75—part of the United States Interstate Highway System, the country’s version of Germany’s Autobahn—was being built almost within arm’s reach of Crosley Field.

Options to aging, tiny Crosley Field had been discussed in Greater Cincinnati since the late 1940s, but nothing had come of those talks. Meanwhile, New York had a vacancy that was screaming to be filled. Cities such as Atlanta, Houston, Dallas, and Denver—growing in population and vibrancy—also were hoping to get a piece of the major league action. A Denver sports leader named Bob Howsam participated in efforts to start a new “major league”—the Continental League, the brainchild of New Yorker William Shea.

Major League Baseball moved quickly to nip that in the bud. The American League allowed its Washington franchise to be moved to Minneapolis-St. Paul and awarded new franchises to Washington, D.C. and Los Angeles. The AL expanded to ten teams and a 162-game schedule in 1961. The disparity in the number of games played by each league and the desire to see the seasons start and end at the same time meant that the NL teams would get more days off—leading to situations such as the Reds getting back-to-back days off in the middle of the last week of the season.

The National League awarded new franchises to New York and Houston but decided to wait an extra year before putting them in play. They would start in 1962 in a 162-game schedule.

While those moves calmed fears of any imminent departure of the Reds from Cincinnati, they did nothing to improve the ballclub. The 1960 Reds finished sixth, their worst since the 1953 team also finished sixth, and their .435 winning percentage (67–87) was the lowest since the 1950 team went 66–87 (.431) while also finishing sixth. They limped home with seven losses in their last eight games, including being swept in three games at Philadelphia in the final series of the season, and nine losses in their last eleven games, going 0–3 against Pittsburgh, 1–5 against the Phillies, and 1–1 against Milwaukee.

Just as bad, if not worse, they drew just 663,486 fans to Crosley Field, the lowest in the majors that season and the franchise’s worst single-season attendance figure since the 1953 team attracted 548,086.

“Nobody expected much out of them,” Ferguson said. “They were really a team with no stars.”

Clearly, something had to be done.