Читать книгу Real Hauntings 5-Book Bundle - Mark Leslie - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Arthur Ellis and an Accidental Beheading:

Canada’s Most Famous Hangman Bordeaux Prison, Ahuntsic-Cartierville

ОглавлениеUntil 1868 executions in Canada were a public affair, held in a common public area, and attracted huge crowds of spectators. After that, executions were moved inside prison walls, mostly cut off from public viewing (historic reports do, however, reference citi-zens attempting to watch the ghastly events from the roofs of nearby buildings). Although the executions became a little less out in the open, certain members of the public were still invited in to view the events. That was, at least, until after a horrific 1935 beheading in front of plenty of public witnesses due to a grave miscalculation by Arthur Ellis.

This macabre event not only changed execution protocol, but it also led to the tragic downfall of Canada’s most famous hangman, a man who called Montreal home and whose body still rests there.

If you venture to Section N of the Mount Royal Cemetery, you’ll find the final resting place of Alexander Armstrong English, known more prominently as Arthur Ellis. English, an ex-army officer, moved to Montreal in 1910 and adopted his working name in a nod to the famous English hangman, John Ellis, after he was recommended to Prime Minster Wilfrid Laurier by British officials. His career was a storied one, however. In an insightful chapter in her book Drop Dead: A Horrible History of Hanging in Canada, Lorna Poplak writes that while it is virtually impossible to verify his claims (since record-keeping in the first couple of decades of the twentieth century was not reliable and other Canadian hangmen might have used the same pseudonym), the man claimed to have performed more than six hundred hangings not only in Canada, but also in England and the Middle East.

Regardless of this claim, there is no disputing the fact that the man was kept busy with his macabre role. A Milwaukee Sentinel article from 1926 outlines the seven-stop tour between Vancouver and Halifax that Ellis was in the middle of, almost as if he were a musician travelling to awaiting crowds in the various cities.

Ellis took great pride not only in his role, but in the skill that he claimed to possess, such as his ability to quickly assess the weight of the condemned after a quick glance at them. The person’s weight was an important factor in a hanging, because it dictated the length of the drop. It’s not commonly known that hangings are not intended to cause death by strangulation, which is slow and agonizing. Rather, they are designed to result in the breaking of the convict’s neck. The quick drop and sudden snapping action separate the vertebrae, which results in almost instant death. The proper length of rope is integral to achieve this effect. This length is based upon a series of tables that originated in Britain and that hangmen in both England and the Commonwealth relied on. If the length of the rope was too short, the condemned might be strangled to death. If the rope was too long, the condemned might be accidentally beheaded.

This latter result is what happened at Montreal’s Bordeaux gallows on March 29, 1935, at the hanging of condemned Montrealer Tommasina Teolis.

Teolis had been found guilty of hiring a hitman to kill her husband, Nicholas Sarao, for a promised five thousand dollars from the man’s life insurance policy. The hitman, Leone Gagliardi, and an accomplice named Angelo Donafrio beat Sarao to death. When they were later caught, Gagliardi confessed and all three were convicted and sentenced to death.

But something went wrong with all three hangings.

Ellis first performed the double hanging (not an uncommon thing for him to do) of Donafrio and Gagliardi. Sadly, the length of the rope for both men was too short and neither of them was killed from the drop; instead, they both died slowly and painfully by strangulation.

THE MEASURED DROP OF HANGING

The accidental dismemberment of Tommasina Teolis involved a miscalculation of her body weight. Ellis and other hangmen used a mathematical formula to calculate precise measurements for the lengths of rope used in hangings, which were derived from a series of tables originating in Britain.

After a number of unfortunate hanging incidents in England, Lord Aberdare and the Aberdare Committee created a standardized table of measured drops, or “long drop,” which would produce what was called a “striking force” of approximately 1,260 pounds of force, which, combined with the correct positioning of the noose, would result in fracture and dislocation of the neck.

The formula was: 1,260 lbs ÷ [prisoner’s weight] lbs = drop (in feet)

The initial table was revised in 1892 to a force of 840 lbs, to reduce the incidents of accidental decapitations, and was again revised in 1913.

Then, in a example of all the things that could go wrong in a hanging, quite the opposite happened when it was Teolis’s turn at the noose.

Her rope’s length was too long.

Ellis claimed that the day before the execution, when he went to the prison to see the woman (having claimed all he needed to do was look at someone to quickly determine their weight), the authorities refused to let him visit her, and instead offered him a piece of paper with her weight written on it.

The weight given to Ellis had been the weight she had been when she first arrived at the prison. But she had gained as much as forty pounds while incarcerated, which threw Ellis’s rope-length calculation off.

The result was horrific. It gained international notoriety. Newspapers all over North America wrote about that fateful day — when instead of her neck breaking, Teolis’s head was torn from her body.

Not only did this gruesome incident result in the ending of public executions in Canada, it also led to the end of Arthur Ellis’s career as a hangman.

In a tone befitting a modern tabloid, a San Antonio Light article titled “Strange Double Life of Mr. Ellis, Hangman” makes some interesting, if not macabre, claims. The article, with the exceedingly long header of “Respected Canadian Political Figure to His Friends, But Executioner to the State Until His Wife Discovered His Jekyll-Hyde Life and Left Him — Then He Bungled His Work, Lost His Job and Has Just Died in Want,” creates a decidedly dramatic portrayal of Ellis’s life that doesn’t appear in many historical accounts.

The article alleges, among other things, that Ellis led a double life, that even his wife was unaware of his actual job, and that he told her he was on some sort of “political mission” when he was travelling across Canada to perform executions. The article states that she left Ellis shortly after finding out about the secret life he was living.

It goes on to state that, prior to moving to Canada to take up the role of hangman, Ellis was morbidly interested in prisons and executions; it was his witnessing of the execution of Mrs. Edith Jessie-Thompson that inspired him. Thompson was sentenced to her death for the murder of her husband and had fainted as she was being led from her cell. She needed to be carried to the gallows in a chair, and was hanged while only partially conscious. After witnessing that disturbing scene in the yard at Halloway Jail, Ellis (or Captain English, as he was known at the time) was impressed by the manner with which John Ellis, England’s official executioner, handled himself and the situation.

The Canadian Ellis did not always handle himself well, however. In fact, he apparently indulged in excessive drinking — a detail mentioned in this article as well as several documents about the man’s life. The article goes on to state that although Ellis rarely appeared in public and particularly avoided mixing with people when he was drinking, he did on occasion venture out — and it was on one such occasion that he was involved in an incident of public violence. According to the article, Ellis had been attending a Montreal theatrical performance, sitting “straight as a ram-rod, a pale, gaunt symbol of death, who must have given an uneasy feeling to both the audience and the actors. Then, without warning, he leaped up, whipped out a revolver and started shooting out the footlights.” The article states that it took half a dozen men to subdue him that evening.

It may be that much of this article is speculation, typical of early 1900s tabloid-style journalism, but the picture painted of Ellis could also be true. In any case, the article certainly shines a dark light on an already dark element of Montreal’s history.

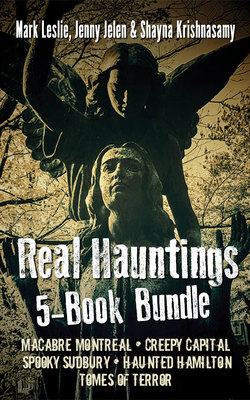

The hanged-man design of the Arthur Ellis Award, named after the famous Montreal hangman.

If he sometimes acted badly in his private life, Ellis was well-mannered in his professional one. His decorum was more than a little disconcerting; in fact, was downright chilling. Ellis, in an interview, claimed that he always smiled at a hanging. Creepy, no? But it’s not as macabre as you might think. “Do you realize that my face is the last living thing the murderer sees before he dies,” Ellis is quoted as saying. “I try to make his last moments as pleasant as possible.”

“Canada’s Leading Hangman Proud of His Skill; Has No Distaste for Grim Job” is the headline of a lengthy July 1935 article in the Evening Democrat, a newspaper out of Fort Madison, Iowa. In that piece, Ellis is described as a “wizened little man,” with keen eyes peering through neat, plain gold glasses, talking cheerfully about the weather in the morning before performing grim executions later that same day. This piece, published shortly after the fateful events in March 1935 that led to the end of Ellis’s career serves a kind of epitaph. It appeared before the final chapter of his life, one of decay and downfall.

Sadly, Ellis died alone, miserable, and without a penny to his name. In Drop Dead, Lorna Poplak describes how in July 1938, a Montreal Gazette article claimed that he had been found in the Ste. Jeanne d’Arc Hospital, emaciated from lack of nutrition and near death. He died shortly after from what was described as an alcohol-related disease.

Less than twenty people attended Ellis’s funeral. Even though they had been separated for half a dozen years, Ellis’s estranged wife attended and was quoted as describing him as a good man. More than twenty years later, when she too passed on, she requested that she be buried alongside her husband. The two are interred in the Mount Royal Cemetery with a simple headstone that states: “Alexander A. English and Edith Grimsdale. AT REST.”

Despite Arthur Ellis’s downfall and miserable last days, he lends his name to an annual gala and awards night hosted by the Crime Writers of Canada. The group honours the absolute best of our country’s mystery and crime writing during the Arthur Ellis Awards. The trophy, nicknamed “Arthur,” comes in the guise of a wooden figure attached to a vertical pole with a noose. Arthur dances and flails when you pull on a string at the back.