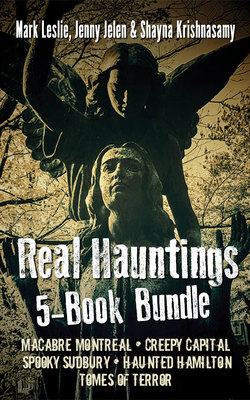

Читать книгу Real Hauntings 5-Book Bundle - Mark Leslie - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Mark Twain’s Montreal Telegraphy The Windsor Hotel

ОглавлениеSamuel Langhorne Clemens, better known by his pen name, Mark Twain, was an American writer, humourist, and lecturer. He is often called the father of American literature. Garrulous in person and a prolific writer, Twain could also be private about his feelings and interests. One aspect of his life that he long kept private was his interest in the paranormal.

Like many of his contemporaries, Twain was intrigued and interested in psychic phenomena. However, though he was a member of the English Society for Psychical Research from 1884 to 1902, he was hesitant to broadcast his beliefs in public. Eventually, though, Twain decided to share his thoughts on the subject. In his essay “Mental Telegraphy” he writes in great detail about his belief in the ability for one human mind to communicate with another over great distances. (It is interesting to note that this article was not published until 1891 in Harper’s Magazine — almost a dozen years after it was written.)

In 1895 Twain published the following article, entitled “Mental Telegraphy Again,” in which he writes about an experience he had while visiting the Windsor Hotel in Montreal.

Several years ago I made a campaign on the platform with Mr. George W. Cable. In Montreal we were honored with a reception. It began at two in the afternoon in a long drawing-room in the Windsor Hotel. Mr. Cable and I stood at one end of this room, and the ladies and gentlemen entered it at the other end, crossed it at that end, then came up the long left-hand side, shook hands with us, said a word or two, and passed on, in the usual way. My sight is of the telescopic sort, and I presently recognized a familiar face among the throng of strangers drifting in at the distant door, and I said to myself, with surprise and high gratification, “That is Mrs. R.; I had forgotten that she was a Canadian.” She had been a great friend of mine in Carson City, Nevada, in the early days. I had not seen her or heard of her for twenty years; I had not been thinking about her; there was nothing to suggest her to me, nothing to bring her to my mind; in fact, to me she had long ago ceased to exist, and had disappeared from my consciousness. But I knew her instantly; and I saw her so clearly that I was able to note some of the particulars of her dress, and did note them, and they remained in my mind. I was impatient for her to come. In the midst of the handshakings I snatched glimpses of her and noted her progress with the slow-moving file across the end of the room; then I saw her start up the side, and this gave me a full front view of her face. I saw her last when she was within twenty-five feet of me. For an hour I kept thinking she must still be in the room somewhere and would come at last, but I was disappointed.

When I arrived in the lecture-hall that evening someone said: “Come into the waiting-room; there’s a friend of yours there who wants to see you. You’ll not be introduced — you are to do the recognizing without help if you can.”

I said to myself: “It is Mrs. R.; I sha’n’t have any trouble.”

There were perhaps ten ladies present, all seated. In the midst of them was Mrs. R., as I had expected. She was dressed exactly as she was when I had seen her in the afternoon. I went forward and shook hands with her and called her by name, and said: “I knew you the moment you appeared at the reception this afternoon.”

She looked surprised, and said: “But I was not at the reception. I have just arrived from Quebec, and have not been in town an hour.”

It was my turn to be surprised now. I said: “I can’t help it. I give you my word of honor that it is as I say. I saw you at the reception, and you were dressed precisely as you are now. When they told me a moment ago that I should find a friend in this room, your image rose before me, dress and all, just as I had seen you at the reception.”

Those are the facts. She was not at the reception at all, or anywhere near it; but I saw her there nevertheless, and most clearly and unmistakably. To that I could make oath. How is one to explain this? I was not thinking of her at the time; had not thought of her for years. But she had been thinking of me, no doubt; did her thoughts flit through leagues of air to me, and bring with it that clear and pleasant vision of herself? I think so. That was and remains my sole experience in the matter of apparitions — I mean apparitions that come when one is (ostensibly) awake. I could have been asleep for a moment; the apparition could have been the creature of a dream. Still, that is nothing to the point; the feature of interest is the happening of the thing just at that time, instead of at an earlier or later time, which is argument that its origin lay in thought-transference.

It is fascinating to consider Twain’s writing about his paranormal experience. The beloved writer and humorist is best known for the riverboat adventures of characters like Huck Finn and Tom Sawyer, but, looking at some of his other works, there is a darker element running through his writing. It’s clear that he was fascinated with death, the dead, and even zombies.

Twain’s most famous reference to death is his oft-quoted retort to an inquiry about his demise: “The reports of my death have been greatly exaggerated.” This is, in fact, a misquote. What Twain actually wrote in response to the 1897 New York Journal claim was, “I can understand perfectly how the report of my illness got about, I have even heard on good authority that I was dead. [A cousin] was ill in London two or three weeks ago, but is well now. The report of my illness grew out of his illness. The report of my death was an exaggeration.”

Twain also wrote about death and the dead on multiple occasions. His darkly comic play Is He Dead? involves an artist whose friends fake his death in order to raise the price of his paintings. The story “A Curious Dream” involves a man witnessing skeletons dragging their coffins down the street, protesting the deplorable condition that the living have let their local graveyard home fall into.

The subject of death is also found in Twain’s two most famous works. Tom Sawyer fantasizes about dying and fakes a death by drowning in The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn includes ghost stories about medical cadavers and a nightmare Pap Finn has about the walking dead.

Clearly Twain was no stranger to writing about the fictional ma-cabre, but it’s interesting that it was an experience in Montreal that inspired a real-life brush with the supernatural.