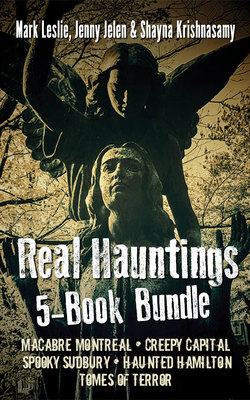

Читать книгу Real Hauntings 5-Book Bundle - Mark Leslie - Страница 23

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Slave Who Burned a City:

The Trial of Marie-Joseph Angélique Old Montreal

ОглавлениеWhile the debate between “innocent victim” or “fierce arsonist” continues to rage, like that once-spectacular fire in the spring of 1734, one thing is clear: The brutal torture and execution suffered by Marie-Joseph Angélique, who was convicted for this crime, also echoes hauntingly from history.

It was in the evening of April 10, 1734, when a startling cry of “Fire!” rang through the streets of Montreal.

Saint-Paul Street was ablaze. As the hospital and church bells rang out their warning, the wind coming in from the west helped the fire spread at an alarming rate. Within three hours, forty-six buildings were destroyed, including the Hôtel-Dieu of Montreal (a convent and hospital). The losses were spectacular. Hundreds of people, both wealthy and poor, suddenly found themselves homeless. Many lost everything they had.

It’s not a surprise that the people of Montreal were quick to identify someone to blame.

That someone was a slave named Marie-Joseph Angélique.

Long before the disaster of the great fire in Old Montreal, Marie-Joseph Angélique’s life was a tragic one. Born in Portugal in 1705, she was sold into slavery in her early teens. First purchased by a Flemish merchant named Nichus Block, she was eventually sent to North America, arriving in New England. It was there she was purchased by the French merchant François Poulin de Francheville, who brought her to Montreal to be a domestic slave in his home. The year was 1725, and Marie-Joseph was twenty years old.

Thérèse de Couagne, Francheville’s wife, changed Marie-Joseph’s name to Angélique, which was the name of her deceased daughter. Though this might seem like a touching tribute, there is nothing sentimental about slavery, and Marie-Joseph’s life in the Francheville household was far from happy. Though unmarried, she had three children while living there, none of whom survived infancy. A slave named Jacques César, owned by a friend of the Francheville family, is believed to have been the father of the children. It’s possible the two were forced to have sex in order to produce offspring.

The one ray of sunshine in Angélique’s life was her lover, Claude Thibault, a white servant who also worked for the Franchevilles. The Montreal community of the time didn’t approve of the relationship between a black slave and a white servant, which is hardly surprising. But given what we know of her personality, it’s unlikely that she cared — for Angélique was hardly a meek and obedient slave. Instead, she is described as stubborn, willful, and bad-tempered, all of which would become more apparent as her hopes of one day winning her freedom began to slip from her grasp.

Francheville passed away in 1733. Sadly, his passing didn’t mean freedom for Angélique, who was still owned by Francheville’s widow, Thérèse de Couagne. Though freedom wasn’t being offered, Angélique took the bold step of requesting her freedom from her mistress in December of 1733. She was denied. It’s at this point that Angélique became furious and incredibly difficult to deal with. She argued constantly with the other servants and talked back to her mistress. She suddenly became obsessed with fire and she threatened to burn the other servants and kill her mistress, also by fire. Servants began to quit service in the Francheville household to get away from her. Angélique was a terror to behold.

Likely as a result of these alarming threats, Angélique was sold in 1734 to François-Étienne Cugnet for six hundred pounds of gunpowder. Cugnet planned to resell the girl in the West Indies. Furious that this was happening to her, and possibly thinking she had nothing left to lose, Angélique threatened to burn down her mistress’s house with Madame de Couagne in it. Shortly thereafter, before she could be sent to Cugnet in Quebec City, Angélique made her first daring move: she ran away.

Her partner on the run was her lover, Thibault. Before running off, the two set fire to Angélique’s bed, further solidifying the association with fire in the minds of the Francheville neighbours. They fled across the frozen St. Lawrence River, aiming for New England and the hope of a boat back to Portugal. Sadly, their escape didn’t go as planned. Delayed by bad weather, they were caught in Chambly only two weeks after their initial escape and escorted back to Montreal. Angélique was returned to Madame de Couagne and Thibault was sent to jail. He would be released in April of 1734, just two days before the Montreal fire.

As the smoke cleared on the morning of April 11, rumours began to circulate that it was the slave Angélique and her lover who had set the blaze. The Canadian Mysteries website points to an Amerindian slave named Marie, dite Manon, as the originator of the rumour, as she claimed to have heard Angélique say she wanted to see her mistress burn. True or not, this rumour was enough for the king’s prosecutor to order the arrest of both Angélique and Thibault. Angélique was apprehended quickly in the garden of the Hôtel-Dieu and taken to jail. Thibault, on the other hand, was never found and is believed to have fled. He was never seen again in New France.

Thus began the most spectacular trial of eighteenth-century Canada. Though trials in those days usually lasted only a couple of days, Angélique’s would go on for six weeks. Charged with arson, she faced possible punishments of death, torture, or banishment if convicted. It’s also important to keep in mind that in those days, the accused was presumed guilty and was expected to prove her own innocence. Lawyers were illegal. Twenty-nine-year-old Angélique had her work cut out for her.

More than twenty witnesses were called to the stand to testify against Angélique. None of them claimed to have seen Angélique set the fire, but they were all convinced she was the culprit. Surprisingly, Angélique’s mistress Thérèse de Couagne was the only one to defend her, insisting her slave was innocent to the very end. But it was the testimony of a five-year-old girl that finally sealed Angélique’s fate. Little Amable Lemoine Monière, a merchant’s daughter, swore she had seen Angélique going up to the attic of the Francheville home with a shovel of live coals in her hand just before the fire started. It was all over.

Angélique’s sentence was a horror in itself. Her hands would be cut off, and then she would be burned alive. Luckily (though is there really anything that can be deemed “lucky” in this story?) the sentence was appealed and lessened. Instead, Angélique was to be tortured, hanged, and her body burned. At this point, awaiting death in a Montreal prison, Angélique steadfastly maintained her innocence; not that it mattered. Torture was a commonplace punishment in this era, meant to illicit a confession. On June 21, 1734, Angélique was subjected to a method of torture called the Spanish boot, whereby the leg is crushed by planks of wood. Under this torture, Angélique eventually broke and admitted to setting the fire — though it should be noted that she never implicated Thibault.

They dressed her in a white chemise, had her hold a burning torch to symbolize her crime, and took her to Notre-Dame Basilica in a garbage cart. It was there that they hanged Marie-Joseph Angélique, displayed her body on a gibbet for two hours, then burned the corpse on a pyre.

Did Marie-Joseph Angélique set the fire that burned down Old Montreal in 1734? It’s impossible to know for sure. Certainly the deck was stacked against her. As a black person, a woman, and a slave, it’s unlikely she could ever have proven her innocence, no matter what she said or did. She was doomed from the moment of her arrest, there’s no question. But an unjust system doesn’t necessarily point to her innocence. Angélique certainly had an interest in arson. She hated her mistress. She yearned for her freedom. She very well might have set the fire.

Perhaps the better question is: does it matter? Her story is so much bigger than this one detail. It brings to the forefront Canada’s participation in slavery, which is often overlooked. It’s the story of an angry woman who was defiant to the last. It’s the story of a love that was never betrayed. It’s the story of a fight for freedom.

The square across from Montreal’s city hall was renamed Place Marie-Joseph Angélique in 2012. It will ensure that her story will never be forgotten.