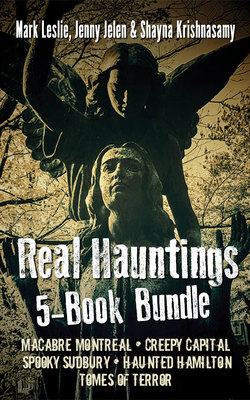

Читать книгу Real Hauntings 5-Book Bundle - Mark Leslie - Страница 36

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Missing Village of Hochelaga The Dawson Site, Downtown Montreal

ОглавлениеIn 1534 Jacques Cartier sailed to the new world under a commission from the king of France to find a western passage to Asia. He planted a cross on the shores of Gaspé, claiming for France the land that would become Canada, and returned home believing he had discovered an Asian island. But we are most interested in his second trip in 1535, when he returned to Canada and sailed up the St. Lawrence River to land finally at the village of Hochelaga.

In a Montreal Gazette article, Marian Scott describes the joyous welcome Cartier and his men received from the Inidgenous inhabitants of Hochelaga. The people danced around the visitors and showered them with cornbread and fish. So much food was thrown into the longboats that it seemed to be raining bread, Cartier wrote in his records. He also gives an account of the village, which he described as being surrounded by a circular palisade that was ten metres high. Inside, there were at least fifty bark-covered longhouses that sheltered about 1,500 people. It was situated among cornfields at the foot of a mountain Cartier named Mount Royal.

Cartier’s descriptions of the village are vivid and there is no reason to doubt their veracity. There is a bit of a mystery about his description, however — it is the only existing written account of Hochelaga. The reason for this is simple: no other European ever saw the village. When Samuel de Champlain returned to the area in 1603, all traces of the village had vanished.

Mount Royal Park. Jacques Cartier arriving at Hochelaga in 1535.

Ever since Champlain’s visit, questions have lingered about the missing village of Hochelaga. What happened to its people? Where exactly was it located? Did it ever exist at all?

If we skip ahead 250 years, we have our first clue. In 1860 remains were discovered by constructions workers digging below Sherbrooke Street, between Metcalfe and Mansfield. Marian Scott reports that a large number of skeletons were found, as well as tools, pots, and firepits. Principal of McGill and pioneer geologist John William Dawson was brought in to explore and evaluate the site, and he came to the conclusion that the former village of Hochelaga had finally been found. The area was thereafter called the Dawson site.

But doubts remained. The Dawson site was much smaller than the grand village Cartier spoke of. Could the village that was unearthed be a different one entirely?

A hundred years later anthropologists Bruce Trigger and James Pendergast set out to examine this very question. Using the carbon dating available in 1972, they were able to determine that the remains did hail from the 1500s. They were unable, however, to definitively confirm that this village was Hochelaga.

Who the Indigenous people living in Hochelaga were and where they went are other unanswered questions. They were long believed to be Haudenosaunee, but Trigger and Pendergast identified them instead as St. Lawrence Iroquoians, a separate nation entirely. In their book Family Life in Native America, James and Dorothy Volo explain that neither the Wyandot nor the Kanien’keha:ka, both of whom believe the St. Lawrence Iroquoians to be part of their ancestry, have a story explaining the disappearance of the people of Hochelaga. Trigger and Pendergast were, however, able to find an elderly man who recounted a story told to him by his father, in which the Wyandot drove his ancestors from the country. According to this story, the nation split, some going southeast to the Abenaki, others southwest to the Haudenosaunee, and still others straight west to other Wyandot.

But does this explain the complete disappearance of the village they were leaving behind?

The search for the missing village of Hochelaga continues to this day. An archeological effort between McGill and Université de Montréal began in the summer of 2017 and was aimed at finally finding the village, with digs planned for Outremont Park, the grounds of McGill, Jeanne-Mance Park, Beaver Lake, and other locations. Construction on de Maisonneuve Boulevard West, at the southern edge of the Dawson site, was recently halted due to concerns about the destruction of artifacts. Interest in the missing village clearly remains.

We may never know much more about the villagers Cartier and his men encountered over 480 years ago. Were they simply nomadic and eventually moved on? Did Cartier miscalculate his location? If so, was the nation he encountered never located in Montreal at all? Or was it a ghost village even when Cartier landed there, already long destroyed, inhabited by spectres so convincingly real that Cartier could not tell the difference? Did the explorer feast with the dead on that fateful voyage in 1535? We may never truly know.