Читать книгу Real Hauntings 5-Book Bundle - Mark Leslie - Страница 24

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Redpath Murders The Redpath Mansion, Downtown Montreal

ОглавлениеOn June 13, 1901, two scandalous murders shook Montreal high society and a mystery that has yet to be solved was born. Two members of the Redpath family, one of Canada’s wealthiest families at the time, lay dead with gunshot wounds to the head. The investigation into the murders was brief, police involvement spotty, and descriptions of the victims — their health and their states of mind, both before and on the day of the tragedy — were contradictory and confusing. The bodies were buried swiftly and very soon the murders were hardly spoken of, almost as though they’d never happened at all.

Questions surround this event: What happened in the Redpath Mansion on that fateful night? How could two such high-profile killings be left unsolved over a century later? And, most importantly, who shot Ada Maria Mills Redpath and Jocelyn Clifford Redpath, and why?

The story of the Redpath family begins with John Redpath, who immigrated to Montreal from Scotland in 1816. Working initially as a stonemason, Redpath quickly opened his own construction business, which was involved in the construction of the Lachine Canal, the Rideau Canal, and the Notre-Dame Basilica. Most notably, he established Canada’s first sugar refinery, Canada Sugar Refining Company (now Redpath Sugar), in 1854. Though Redpath passed away in 1869, his extensive family (he had seventeen children) continued to enjoy the wealth amassed by his many successful business ventures, and by 1901 were firmly entrenched members of Montreal’s elite.

John James Redpath was John Redpath’s tenth child. He would grow up to work in his father’s sugar refinery business, and in 1867 married Ada Maria Mills. He and Ada had five children: Amy, Peter, Reginald, Harold, and Jocelyn Clifford, known as “Cliff.” It’s here, in this branch of the Redpath family, that we find the major players in the Redpath mansion murders.

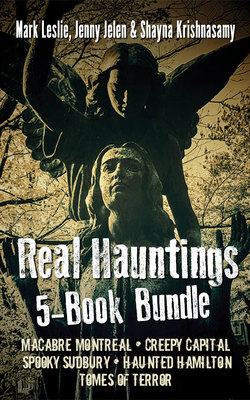

Ada Maria Mills and four of her five children.

Much of the minute-by-minute account of the murders on that day in the summer of 1901 can be found in the coroner’s inquest documents, which includes testimony by Ada’s son Peter. It is said that Cliff, aged twenty-four, returned home at about 6:00 p.m. on June 13 and went straight to his mother’s room. Seconds later his brother Peter heard shots ring out.

After breaking down the door to the room, Peter found his mother and brother lying in pools of blood next to a revolver. According to a Montreal Daily Star article published the next day, Ada was already dying when Peter arrived but Cliff was rushed to Royal Victoria Hospital and died just before midnight.

There were no witnesses to the murders other than the victims themselves, and so it’s impossible to know the most basic facts, such as who was shot first, who was holding the gun, what the two victims spoke about just before their deaths (if anything), and why one of them had a gun to begin with. Whether Ada or Cliff had a desire to die or to kill the other is also impossible to know, but we can speculate.

Reliable information about Ada Maria Mills Redpath isn’t easy to come by. We know she was the daughter of John Easton Mills, who was elected mayor of Montreal in 1846 (and also shows up in the chapter “The Heroic Death of John Easton Mills”). We know that by 1901 she was the mother of five children and a widow (her husband, John James Redpath, died in 1884). We know that she was in poor health. And we know that she died after being shot in the head. Other details, even her exact age at the time of her death, are difficult to pin down. The Canadian Mysteries website states that Ada was born in 1842, which would make her fifty-nine at the time of her death. Other sources claim she was fifty-six, sixty-two, and forty-five, and one of those sources was her own child.

The exact nature of the ailments that plagued her is also difficult to ascertain, mainly due to the limits of medical knowledge in 1901. One source reports that she suffered from “ulceration of the eyes, neuralgia of the jaw, painful joints (which involved the fitting of a brace), and melancholia.” After the murders, the New York Times stated that Ada “had been ill for some time, suffering greatly from insomnia.” The Globe reports that Ada suffered from “partial paralysis of one side,” though this isn’t corroborated by any other sources. Most reports agree that today Ada would likely have been diagnosed with depression, though how severe it was is unclear. Canadian Mysteries claims she regularly spent time in a sanatorium and by 1900 hardly ever left her room. At the time of her death, Ada was in such poor health that she relied on her children to care for her. Of the five children, Amy and Clifford tended to her the most.

How sick and depressed was Ada? Depressed enough to take her own life? Reporters of the time seemed to think so. The Halifax Morning Herald reported in June 1901 that “while temporarily mentally deranged, Mrs. Redpath attempted to end her life, and in attempting to prevent her, the son was shot. The unfortunate lady then completed her undertaking.” Similar stories came out in the Calgary Herald and the Winnipeg Free Press, and Manitoba’s Swan River Star agreed with that description of events in an article that came out far later in the month.

But the coroner’s inquest into Ada’s death came to a different conclusion. The verdict was quite clear:

Ada Maria Mills died at Montreal on the thirteenth day of June nineteen hundred & one, from a gunshot wound apparently inflicted by Clifford Jocelyn Redpath [the order of his names is written incorrectly in the report], while unconscious of what he was doing and temporarily insane, owing to an epileptic attack from which he was suffering at the time.

Is this true? It’s time to turn to Jocelyn Clifford Redpath, Ada’s youngest son. Having recently graduated with a degree in law from McGill, Cliff was studying to take the bar exam that summer. The Montreal Daily Star described Cliff as popular with his fellow students, ambitious, and interested in canoeing and horseback riding, all the traits of a picture-perfect young man of wealth. But outward appearances can be deceiving. Did Cliff’s enviable exterior hide a distressing inner life?

Like his mother, Cliff was also said to have suffered from insomnia, according to the Montreal Daily Star. Dr. Roddick, the family’s physician, who was called to the house on the night of the murders, had a lot more to say about Cliff, claiming he was epileptic, suffered from a neurological condition, was studying overly hard for his upcoming exam, and was stressed about having to care for this mother. Though he didn’t for a moment suspect Cliff of violence, Dr. Roddick stated that, given his many burdens, he wasn’t surprised the young man lost his mind.

Once the coroner’s inquest declared Cliff to be the killer, the epilepsy explanation was printed in papers nationwide. As corroborated by a Dr. Rollo Campbell, who spotted foam in Cliff’s mouth (evidence of an epileptic fit), this easy, tied-with-a-bow solution to the puzzling deaths seemed to satisfy some. In this version of the night, Cliff lost control during an epileptic seizure and shot both his mother and himself, though it’s never quite clear if one — or both — of the shots was accidental.

Looking at this explanation today, some glaring issues become apparent. To begin with, epileptics are no longer assumed to be insane, and an epileptic seizure would never hold up in court as a reason for murder. Insomnia isn’t known to drive anyone to murder either, though it’s widely noted that both Ada and Cliff suffered from the affliction, as though this is somehow a motive. Studying too much is also a flimsy excuse for homicide.

Of course, Cliff might have accidentally shot a gun while having a seizure, but that doesn’t explain what he was doing holding the gun to begin with. However, the press was keen to solve this mystery. Both the Grandview Exponent and the Quebec Daily Mercury reported that Cliff had been drinking on the day of the murders and that during a quarrel with his mother he shot both her and himself. La Presse insisted Cliff was deeply depressed. Cliff’s brother Peter, whose story seemed to change drastically each time he was interviewed, eventually claimed that his brother was homosexual and he’d told his mother for the first time that day. This led to their argument and the subsequent shooting.

But each of these stories has its holes. In a contemporary article about the murders, Jeannette Novakovich claims Cliff’s bar exam date was only a month away, and he’d already paid the fee, evidence that she believes shows he wasn’t depressed or suicidal as other sources claim. There are no other reports of Cliff being gay. And returning to the epilepsy explanation, Novakovich points out that Cliff is never once stated to suffer from the condition in the many Redpath family diaries, not even once.

Mother kills son and then herself, or son kills mother and then himself. Neither explanation is particularly convincing, and so many questions remain, the main one being why? With that question in mind, we must turn at last to the strange events that took place after the bodies were discovered.

To begin with, no one called the police. The Calgary Herald reports that the police only heard of the murders by accident. The coroner’s inquest states that three doctors were called instead. They confirmed Ada’s death and came forth with the suspicion of an epileptic fit. Another strange thing to note is the extreme swiftness of the inquest and the burials, both of which were complete by June 15, just two days after the murders. There is little to no evidence that any investigation into the murders was conducted by the police beyond that day.

Novakovich explains that the Victorian obsession with keeping up appearances and sweeping unpleasantness under the rug could explain why the deaths were dealt with so quickly and hardly spoken of thereafter. If she’s right, the Redpath murders could be a simple case of accidental death that nobody wanted to talk about, a mystery that lived on mainly due to our overactive imaginations. Or maybe not.

Maybe the Redpaths had a killer in their midst, and didn’t want anyone to find out. Maybe Ada wasn’t an invalid but was hidden away due to her alarming tendency to pull out a revolver without warning and shoot off a couple of rounds. Maybe Cliff really was an angry drunk set on killing his mother. Or maybe the murderer was someone else entirely. After all, there was an entire mansion full of rooms to hide in that night, rooms that, it seems, nobody searched. Rooms the Redpath mansion murderer might have retreated into, slipping deep into the shadows and out of sight forever.