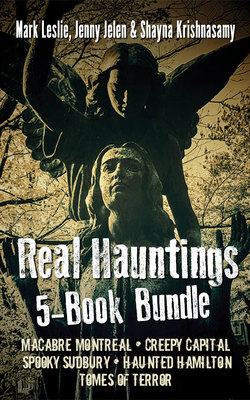

Читать книгу Real Hauntings 5-Book Bundle - Mark Leslie - Страница 39

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The McGill Student Who Killed Houdini The Princess Theatre, Downtown Montreal

ОглавлениеHarry Houdini was born in Budapest on March 24, 1874, and he died in Detroit on October 31, 1926. But the man, whose birth name was Erik Weisz (later Ehrich Weiss, finally adopting his well-known name when he began his career as a professional performer) sealed his fate in Montreal on Friday October 22, 1926, due to a series of sucker-punches he received from a McGill University student by the name of J. Gordon Whitehead.

In a 2004 book titled The Man Who Killed Houdini, Don Bell tells the story of that event. He spent almost twenty years speaking to eyewitnesses and gathering the research to tell a very full and thorough tale about the man responsible for the death of someone who was, perhaps, the world’s most famous and legendary escape artist, magician, and illusionist.

Bell documents the many different interviews and conversations he had with various people, sharing in detail the conflicting accounts from multiple sources about the specific time, place, and circumstances surrounding the escape artist’s infamous demise. Among the tales, Bell stitches together multiple accounts to create a document about Houdini’s death, but also the man behind the legend.

According to Bell, Whitehead, along with two colleagues by the names of Samuel “Smiley” Smilovitz and Jacques Prince, entered Houdini’s dressing room prior to one of the illusionist’s Montreal performances. There they found the magician reclining on a couch. After some conversation in which Houdini remarked about the abilities of the human body to prepare for intense physical feats, such as being able to withstand a strong blow to the stomach, Whitehead unexpectedly hit Houdini in the stomach, landing at least two, if not as many as four or five, hard punches. Since he was still lying down and not expecting it, Houdini had not been prepared for the series of sucker punches he received.

Almost immediately after the attack, Houdini began to suffer from severe abdominal pain. Nevertheless, as a man who rarely let physical pain or discomfort prevent him from performing (prior to his Montreal stint, he had performed a show in Albany with a broken ankle), he continued on with his scheduled shows at the Princess Theatre that night and the next day.

Montreal’s Daily Star theatre critic described the performance, which took place in front of an “audience that packed every corner of the edifice.” For three hours, they watched with undivided attention “the feats of that master-magician, Houdini, as he gave them a display of legerdemain, illusions, mysteries and the most astonishing of tricks, concluding with an exposé of the fraudulent spiritist mediums who batten upon a gullible public.”

This publicity shot shows famed boxer Jack Dempsey pretending to throw a punch at Harry Houdini, who is being held by Benny Leonard.

Following his Saturday performance, Houdini and his entourage boarded a train for Detroit. Despite the terrible agony he continued to experience, he knew there was no time for rest because of the two-week booking at Detroit’s Garrick Theater.

Although he collapsed in the wings, overwhelmed by high fever and pain, Houdini continued to perform. Afterward, he was rushed to Grace Hospital in Detroit and diagnosed with acute appendicitis. Two separate operations were performed on him, but the poison from his ailment had already seeped into his blood and he was diagnosed with streptococcus peritonitis. On the afternoon of Halloween in 1926, Houdini whispered to his brother Theo, who had been standing at the man’s bedside, “I’m tired of fighting, Dash. I guess this thing is going to get me,” and, shortly after, succumbed.

There continued to be debate in the medical community about whether or not the severe blows could have caused the affliction that killed Houdini. But it is entirely possible that the pain from the hard punches he received might have masked the underlying pain from the appendicitis, and, inadvertently, delayed the prognosis. There was also some speculation that the popular showman’s ongoing tirade against fraudulent spiritualists might have angered the local medium community enough to make them hire a student like Whitehead to viciously attack the magician.

It was determined that Whitehead was probably nothing more than a hot-tempered young student trying to prove a point … a point that had consequences well beyond that fateful moment. Most historical accounts report that Whitehead simply seemed to drop off the face of the earth, but Bell, in his decades-long research, managed to track down a number of details about the man.

Jack and Frances Rodick, owners of a Montreal bookshop, relayed how one evening in the shop Whitehead had shared with them that the incident was a sad and irresponsible moment that truly haunted him. “When he told us about his involvement in punching Houdini,” Frances Rodick said, “I didn’t think he intended what happened but he wanted to show Houdini up. Like ‘Is that what you think? Then I’ll show you!’ And of course he did hit him.”

“I felt,” Jack Rodick said, “that as a student he might have been brash about this sort of escapade, but afterwards he didn’t seem at all proud of it.”

“Whitehead may have felt like he committed a terrible crime,” Frances concluded. “I certainly sensed a deep sadness, and it was probably what made him ill.”

Whitehead died sick, troubled, and “thin as a reed,” living in a dark apartment surrounded by gigantic piles of magazines and newspapers, which he kept arranging and rearranging in different locations. He was described, by the few people who knew him, as a gentleman and intellectual. He, perhaps, lived the remainder of his life in the shadow of the knowledge that his youthful actions as a McGill student might have resulted in the death of a man whose legacy continues to astonish people from around the world.