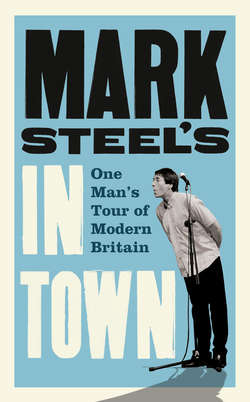

Читать книгу Mark Steel’s In Town - Mark Steel, Mark Steel - Страница 10

Didcot, Oxford

ОглавлениеDidcot must be the town that’s least visited compared to how often it’s seen in the whole country. It’s in the south of Oxfordshire, and consists of two main roads on either side of a tiny pedestrianised centre, a small railway museum, a fire station, a post office and a fucking great power station with six vast funnels pumping out fuck knows what that can be seen from everywhere, including, I should think, on a clear night, outer space.

If you’re travelling to the Midlands by road or rail, you might casually glance west and note a power station. That will be Didcot. If you’re going to Bristol, you might at some point turn towards the north and see a power station. Didcot. Even when you’re used to this you get caught out, and think, ‘That power station can’t possibly be Didcot,’ but it will be, because it’s on wheels and they must move it to comply with regulations regarding smoke limits in one area.

It may not be coincidence that it’s visible from so much of England, because Didcot was the perfect place for southern England’s main railway junction, en route to everywhere, in the middle of everything. Many towns grew up around a railway, but in Didcot the railway was the town, created to serve Brunel’s vision of a network from east to west. You’ll probably now be wondering how you can read much more about the impact of the railway on Didcot, in which case you may be drawn to a book I bought called The Railway Comes to Didcot. But unfortunately the opening line goes: ‘In no way is this book a history of the railway in Didcot.’ I couldn’t help feeling slightly cheated by this. It’s possible that another of the author’s books may contain some information in that area, but I was slightly put off by its title: The Long Years of Obscurity: A History of Didcot, Volume One – to 1841.

Didcot owes its modern existence to Lord Abingdon, who refused to allow a railway to pass through Abingdon village; Didcot was chosen instead. Now it has around 20,000 people, and a sense that the landscape might not be something to put on a tin of biscuits.

When I asked on Twitter for comments from the town, possibly the two most poignant were, ‘You can always tell on the train to Oxford who’s from Didcot, from their morose demeanour,’ and ‘I seem to remember a character in EastEnders confessing they were from Didcot.’ That is truly disturbing, to be considered a subject of trauma in EastEnders, presumably with dialogue that went:

‘We’ve gotta talk.’

‘What is it, doll?’

‘Look, this ain’t gonna be easy, but I’ll come aht wiv it. I’m from Didcot.’

‘You what? Oh no, that explains your morose demeanour, you slaaaag.’

But the town has developed a stoical sense of pride. Everyone I spoke to there was aware of the Cornerhouse Theatre, which they told me with great satisfaction had been built with money originally scheduled for Reading. And everyone was shocked, shocked, that I wasn’t familiar with William Bradbery, who came from Didcot and was the first person to cultivate watercress.

As well as being defined by, and looked down upon from all angles by, the towers of the power station, Didcot is also defined by, and looked down upon from all angles by, the town ten miles up the road, which is Oxford.

To start with, in 1836 the Great Western Railway applied to build a branch line from Didcot to Oxford, but the colleges were the main landowners, and they refused to allow the new route. The reason was that they didn’t want the grubby people of Didcot to be able to lower the tone of Oxford by merrily travelling to it on the train. Eventually in 1843 the colleges allowed the new line, but on the condition that no one below the status of an MA was allowed to travel on it. Now, when I first read this, I was certain that I must have misread or misunderstood the sentence, so to save you going back over this paragraph, eventually in 1843 the colleges allowed the new line, but on the condition that no one below the status of an MA was allowed to travel on it.

Not only that, but the university authorities were given free passes to travel along the line at any time, to check that no one was trying to catch a ride who wasn’t sufficiently mastered up. So there were actually people looking through the carriages, maybe even wandering down the train calling, ‘Can I see your Masters, please? Masters and doctorates, please. Thank you, Professor. Thank you, sir, that’s fine. Ah, I’m sorry, sir, media studies isn’t valid on a Friday, you’ll have to get off at the next stop.’

If it hasn’t already received one, I’d like to nominate this for the all-time snobbery award. When discussing their proposal the university authorities must have said, ‘It is quite possible that not being able to speak Latin is contagious, in which case for our finest minds to be in the proximity of these Didcottian dunces could be calamitous to our nation’s intellect.’

Hopefully the local youngsters found ways round this rule, by flashing a 2:1 in geography at the barrier, then running off before the inspector could check it. Or maybe they forged a BA in philosophy, and then rather than squirming as the inspector asked them for a précis on Cartesian dualism, they panicked and locked themselves in the toilet.

But it would be a mistake to think of Oxford as a monolithic body of pomposity, because the town is divided between the university hierarchy and a normal population. This has given rise to a tension that goes back to the early days of the colleges in the thirteenth century, and that erupted spectacularly in 1355, when two students complained to an innkeeper about the quality of his beer. According to one account, they ‘took a quart of wine and threw the said wine in the face of the taverner, and then with the said quart pot beat the taverner’. The students then fetched bows and arrows, but these were confiscated by local bailiffs, so more students turned up and attacked the town magistrates. A complaint by residents was made the next morning, so the students, being young and full of mischief, set fire to the town. At the end of the day’s fighting sixty students and thirty-three people from the town were dead. By this time I presume the landlord had cleaned his barrels and freshened up his beer.

You might imagine some sort of sanction would have been applied to the students who started this jape, such as a couple of marks knocked off their business studies final paper for every blacksmith they murdered, or something. But the government blamed the people of the town for the incident. So each year the mayor, bailiffs and sixty burgesses of the town had to attend a mass, and pay a silver penny to the university for each dead student. This penance carried on until 1825, when there was probably only the Daily Mail left screaming that if criminals can get away with a 490-year sentence, it’s no wonder the streets aren’t safe.

Today the rift between university and town ought to be less pronounced than in the days when students were almost exclusively from the nobility, but this is complicated by the fact that in Oxford the students are Oxford students. Some of them, though a smaller percentage even than fifty years ago, may be from working-class backgrounds, but all of them are imbued with a sense of superiority. As you head through the centre of town past the courtyards, the gothic buildings, the boys in black gowns, the quaint bridge that seems designed to tempt you to jump off it into the Thames at two in the morning, the perfect lawns, the entrances behind thick spiky chains, you feel as if you’re at a gig with only a white wristband, but you need a purple one to get past the ropes and the security staff to where people like you aren’t allowed.

Even so, the town is seductive, with pubs covered in ivy that make you feel as if you should sit at an oak table with a jug of ale being wise, and gentle paths by the river where you have to delicately brush away dangling lengths of weeping willow to walk along them. It’s hard to reconcile yourself to the fact that this is the same Thames that charges through London all full of rage. It seems as if the river must go there to work all day, then commute back home to Oxford and relax by gently rippling past muddy banks on which there ought to be an old man showing his grandson how to whittle.

So it must seem peculiar to live there if you’re part of the population that has no business with the university. Because Oxford’s college’s aren’t to one side of town, like most work-places that dominate an area, by the docks or on an industrial estate. They’re stood, grandly, peering at you from all angles, reminding you that beyond the gables and the statues are your masters and future masters, and probably a function at which someone’s carrying a tray of tiny sausages to honour a benefactor from the Wellcome Trust.

This is a world that certainly isn’t dominated by the soulless and the corporate, with no room for individuality. Here they saunter across quadrangles between spires and gargoyles, every delicately designed corner of every building intricately unique.

A chancellor of Oxford University would be facing controversy, I would imagine, if he suggested that the colleges should be relocated in a huge education park and become part of chains called First for Firsts and Masters-rite.

Yet there is a town behind these buildings that functions normally. Over the river and past the station are the nail salons and pound shops, the Westgate shopping centre with its Vision Express and Nando’s. It does have a retail park, and a nearby depleted car factory, and a football team that slid out of the League but came back again, and postmen and a Big Yellow Storage Company.

Occasionally the two worlds collide. Walking across the bridge to the normal part of town, I met a professor. ‘Excuse me,’ he said, in a controlled slur that suggested he’d had practice at trying not to seem drunk. ‘Can I talk to you for a moment?’ He had a tight cravat and a short sheepskin coat, and asked again, ‘Could I, just for a moment?’

I said, ‘Are you homeless?’ and tried to give him some change.

‘Good Lord,’ he said. ‘No, I’m certainly not homeless. I’m a veterinary surgeon and a professor, and I’m very sorry.’

‘Why are you sorry?’ I asked him. ‘Did you sew up the wrong end of a rabbit?’

‘Oh, I’ve done that many times,’ he said. I wondered if I’d landed in an Eastern European novel, and the day would end with me whipping a dwarf.

‘Are you sorry because you’re meant to be with your wife, and you’re late because you’ve got drunk?’ I asked.

‘My dear dear darling wife has come to expect that of me, I’m afraid,’ he said. ‘No, I’m sorry because I have to be at a college function and I’m not sure where it is. I don’t suppose you know where it is, do you?’

I tried to get a clue as to how I could help, but it was always unlikely that I’d be better informed than him about the whereabouts of a function in a college in his city to which he’d been invited.

We carried on in this surreal fashion for about ten minutes, then he put his hand on my shoulder and said, ‘Well, it’s been lovely talking to you. The main reason I wanted to talk to you is that I was a bit lonely, I’m afraid.’

As he walked off, I concluded two things. Firstly, if I ever have a sick pet I should look him up, as he’d probably be a lot of fun, and even if he was a little shaky with a scalpel, he’d appreciate the company. And secondly, while glorious spires, immaculate lawns and vast gothic wooden doors are inherently more beautiful than smoky putrid power-station cooling towers, I think I prefer Didcot.