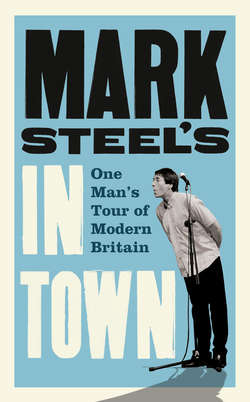

Читать книгу Mark Steel’s In Town - Mark Steel, Mark Steel - Страница 13

Horwich

ОглавлениеThe generalisation that all Londoners are grisly and unfriendly while northerners whistle all day and give away their houses to strangers is clearly a myth. But there are plenty who insist that this irrational idea is true. You could cite any example as evidence to the contrary, and they’d say something like, ‘Yes, but at least the Yorkshire Ripper would lend his neighbours a cup of marmalade, even on the morning of a murder.’

But some people will work tirelessly to fit the stereotype. To sight the snarling Londoner the best method is to ride through the capital on a pushbike. The first time you hear someone lean out of a window and screech, ‘Get out of my way, you fucking cunt!’ you might be slightly peeved. But then it becomes fascinating. Sometimes their rage is so overwhelming you’re captivated by the veins pumping out of their neck, and it seems they’re physically unable to reach the end of the word, so they yell, ‘Cuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuu’ until you’ve turned right and into the next street never knowing whether they got as far as ‘nt’, or if they had to go to the doctors, still growling ‘u-u-u-u-u-u-u-u-u’ like a stuck CD until they’re given an injection.

One morning, on the north side of Vauxhall Bridge, I pulled up at the lights next to a gargantuan lorry. One of the essential rules of cycling in London is, when you’re at traffic lights, to make eye contact with the motorist behind you, to be certain they’ve seen you, especially if they’re driving a gargantuan lorry. Nearly always the motorist smiles or waves or acknowledges you in some innocuous way, but this time the driver wound down the window and snarled as if gravel was swilling round his voicebox, with every consonant emphasised for maximum snappiness, ‘What’s your fucking problem?’

‘I’m just making sure you’ve seen me, mate,’ I said, being slightly dishonest with the word ‘mate’. And then he spread his frame and breathed in, as if preparing for a roar like Godzilla, and yelled, ‘I pay road tax. You pay fuck off.’ Just imagine the anguish rolling around in this driver’s head at that moment. Presumably he was thinking, ‘Here is the ideal opportunity for me to convey my thoughts on the iniquities of our road-funding system, whereby he is considered exempt from contributions in spite of using the roads as much as me, albeit on two wheels as opposed to my 184, and that, in my view, is inconsistent and must be redressed. But at the same time, I can’t wait to tell him to fuck off. Oh no, now I’ve combined the two, and it’s come out grammatically incoherent.’

On the other hand, to spot a swarm of neighbourly northerners chatting to each other on pavements you should try Horwich, a couple of hills from Wigan and four miles west of Bolton, at the foot of the South Pennines. It’s a town of about 23,000 that grew around a railway works, and since that shut down everyone seems to spend all day chatting. I became familiar with Horwich from 2007, when I first met my wife.* That meant I got to know the neighbours, which means everyone, and join them in midstreet chats. One day a woman called Betty tried to stop me for a chat while I was going for a run. ‘Oh, hello love. How you getting on? Only, I’ve been meaning to ask you –’ she said, as she leaned on her shopping trolley while I jogged by in my shorts.

As I called out, ‘I’m going for a run at the moment, Betty,’ I felt as if I’d committed a dreadful crime, as the etiquette here is always to stop and chat, even if you’re fleeing for your life from a maniac with an axe. Even then you’d probably be all right, because the maniac would have to stop and chat as well, until after forty minutes he’d be told, ‘Anyway, love, I can see you’re busy so I shan’t keep you,’ and all being well you’d both set off again at the same time to keep the chase fair.

In another forlorn attempt to be physically active I went for a swim at the leisure centre, and in an inept moment I veered to one side and brought my foot down and across those plastic baubles used to divide the pool into lanes. It was enough to cause a stifled yelp and make me turn round to see what damage I’d done. I could see the foot was cut, and little streams of blood were starting to create mesmerising shapes. At that point a woman swimming towards me in the next lane stopped and said, ‘Oo, hello, oh, you don’t know me, love, but I’ve seen you on TV on, oo, what was that programme, anyway I said to my husband I’ve seen you round Horwich, I said to him, “I’m sure that’s Mark Steel I saw popping into the grocers on Winter Hey Lane.”’