Читать книгу Mark Steel’s In Town - Mark Steel, Mark Steel - Страница 6

INTRODUCTION

ОглавлениеWhat’s the point in going anywhere if the place you go to is the same as the one you left? Who’d bother going on a holiday that was advertised as: ‘Visit the magic of the Seychelles, it’s IDENTICAL to your own house.’

Imagine if in Tunisia, instead of the background of the call to prayers, the mosques played Magic FM. Or if Paris didn’t have that slightly exotic drainy smell, because EU regulations had compelled the place to be cleaned with Jif.

Once, in the New York subway, a huge woman barged into me and yelled, ‘Hey, out my way asshole!’ And it was marvellous, because that’s what’s supposed to happen in New York. It was as exciting as when I was nineteen and went to Amsterdam and bought a lump of dope off a man in a woolly hat but it turned out to be mud.

After taking the trouble to go to the Lake District you want it to smell of cow pats, and at Blackpool you want everything to look as if it should be in a Carry On film.

Having toured Britain plenty of times, usually to talk to an audience for the evening, I find these local quirks compelling. For example, on the way to Skipton, in North Yorkshire, I noticed a road sign to a town called Keighley. Later, during the show, I asked the audience, ‘Is Keighley your rival town?’ And the room went chillingly quiet, until one woman called out with understated menace, ‘Keighley – is a sink of evil.’

There was something delightful about this, because it was an expression of specifically Skipton malevolence.

Similarly, I went to Merthyr Tydfil, a blighted town at the top of the Rhondda Valley that’s been shut down bit by bit. After the show the manager of the theatre told me, ‘People often come in and ask what time a performance is starting, so I’ll tell them, “It starts at seven-thirty,” and they’ll say, “Oh, that’s a pity. I won’t be able to come to that, as I’ll be drunk by then.”’

And somehow there was a warmth to hearing that, because it was a story of distinctly Merthyr despair.

Before appearing in Stockton-on-Tees, in the North-East, I was sent a message on Twitter by a local resident that said: ‘This town is where Joseph Walker invented the safety match in 1834. Before that, when we wanted to set fire to upturned stolen cars we had to rub two sticks together.’

And before my visit to Cambridge, someone sent me a message about the town saying, ‘This place is Hogwarts for wankers.’ It was a cosy thought, because it could only apply to Cambridge, and ought to be the slogan on the masthead of the local paper.

The elements of a town that make it unique are what make it worth visiting. But also, any expression of local interest or eccentricity is becoming a yell of defiance.

Because the aim of society now seems to be to make every city centre so depressingly identical that if our town planners were put in charge of Athens, they’d knock down the Parthenon and replace it with a shopping mall called ‘The Acropolis Centre’, with an announcement that there was much excitement, as the new centre would have a River Island and a Nando’s.

You could be dropped blindfolded into a city centre you’d never been to before, and guess correctly that there’d be a Clinton Cards just there, then a Vodafone, Carphone Warehouse, Boots, Specsavers and Next just there, with the anti-vivisection stall there, and on a Saturday you’d hear a ‘pheep’ and know the Peruvians were about to start on the pan pipes just there, and within the hour they’d have pheeped their way through ‘Mull of Kintyre’ and ‘I Just Called to Say I Love You’ and ‘Ob-la-di Ob-la-fucking-da’, as I believe it’s now officially called.

With equal confidence you could predict that just out of town there’d be a concrete expanse containing a giant Tesco, PC World, Majestic Wine Warehouse, Comet, Dreams, and an unfathomable junction with traffic lights facing in all directions that makes no difference anyway, as every turning forces you into the car park at Iceland and there seems to be no way of escaping except by reversing through the checkout at Carpet Right.

Somewhere in this world there must be someone who is immensely proud of having invented the multi-storey car park, which is often the introduction to a new town, as you sink into the trance that allows you to endure the shuffle through traffic towards this disturbing dungeon, where you descend and descend through a chilling gloom that would make Richard Dawkins say, ‘Bollocks to that, I’m sure there are ghosts down here,’ to level 5, where you think you spot a space but it turns out to be an illusion created by a snugly placed Fiat Uno, past levels 5a and 5b, so you’ve now forgotten what natural sunlight could ever be, like future generations forced to live in a bunker following a nuclear war, until you find a gap by a leaking pipe that leads to a line of green slime. At which point you’re unlikely to take a deep breath, like a nineteenth-century traveller, and exclaim, ‘Aha, and this is Taunton.’

Later you’ll have to queue at the one paypoint that hasn’t got a sheet of paper with a wonky ‘Out of order’ sign Sellotaped to it, which will be two floors away and up some steps that are so grimy that if you meet someone coming the other way it seems impolite not to murder them.

It’s not the ugliness of modern towns, in a Prince Charles sense, that makes them so dispiriting; it’s the soullessness. You know they’ve been plonked there as a result of some regional coordinating business advisory committee that’s copied the model of what’s been built in 3,000 other towns.

It’s as if they’re part of a new world, of call centres and chain pubs and clubs, in which the faceless corporation dictates how a town looks and lives and even, with its scripts for the staff of restaurants and call centres, speaks.

So the shops, the customs, the traditions and accents, the hip-hop lyrics, the football chants, the absurd rivalries that apply to one area are preserved almost as an act of rebellion, in place because the people who live with them have kept them going, and not because they’ve been placed there following a board meeting in Basingstoke.

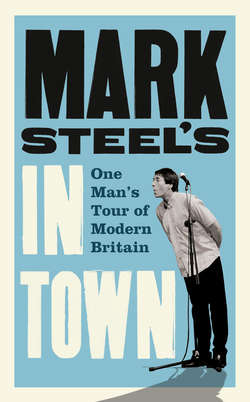

This book is about some of those glorious human differences that comprise the heart of each town. It follows a series I made for BBC radio. Sometimes I’m asked how I select the towns to write about, but I’m not sure of the answer. I did feel a twinge of power when a butcher told me he’d gone to Skipton with his wife for a weekend after hearing one of the shows – for a moment I knew how Nigella Lawson must feel when she mentions that she sometimes has a gherkin with cheese on toast, and by ten o’clock the next morning some idiot’s bought the world’s supply of gherkins.

But as far as I’m aware I choose them fairly randomly, because the main point is that you can look at anywhere at all, and within a day discover enough history, grubbiness, madness and inspiration to realise that it is a distinct and unique cauldron of humanity.

For example, one drizzly dark February afternoon as I came out of the station at Scunthorpe, I got in a minicab, and the driver didn’t even look at me, but kept staring straight ahead as he said, ‘I don’t know what you’ve come here for, it’s a fucking shithole.’

And that’s made me remember Scunthorpe ever since.