Читать книгу Still I Rise - Marlene Wagman-Geller - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

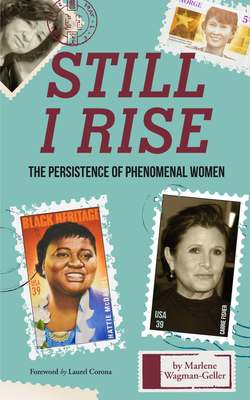

ОглавлениеPROLOGUE: HELL, I’M STILL HERE

“A woman is like a teabag; you never know strong it is until it’s in hot water.”

— Eleanor Roosevelt

Anyone who has managed to survive to mid-mark of the biblically allotted three score years and ten has had occasion to cast one’s eyes heavenward and mutter, “Ya know, God, there are other people.” Amidst these litany of woes can be discerned cries of betrayal, illness, lost illusions. After all, part and parcel of living means treading the Boulevard of Broken Dreams, navigating the Canal of a Shattered Romance. What eases the thorny path is the belief we do not have a monopoly on grief, that loss is a universal condition. Another weapon in the arsenal of endurance is the hope we can rise from our knees. In the words of Oprah, “Turn your wounds into wisdom.”

In a nod to the sweet is sprinkled with the bitter; while celebrating the launch of my fourth book, Behind Every Great Man, was the pain I experienced from watching a lady I love grappling with a tsunami of tsoris that through solidarity became my own. For solace I turned to women who had conquered their own emotional Everest—who not only refused to crumble, but prevailed. The first of these possessors of indomitable spirit I investigated was Hattie McDaniel. She was the thirteenth child born to former slaves and her life was a struggle against grinding poverty, racism, four failed marriages, and a hysterical pregnancy. Rather than bow to defeat, she arm-wrestled Jim Crow and broke the color barrier in film to become the first African American to win an Academy Award for her portrayal of Mammy in Gone with the Wind. In her emotional acceptance speech, she stated she hoped she was a credit to her race. She was—and not just to her race, but the human race.

Aung San Suu Kyi went from two decades of house arrest in Burma to Sweden’s Nobel Peace Laureate. Rather than vow vengeance on the regime who had stolen her life, she sought to negotiate with the junta; however, so far it has chosen to ignore her. She stated with her indefatigable humor sweetened with temperance, “I wish I could have tea with them every Saturday, a friendly tea. And, if not, we could always try coffee.”

Nobody feels sorry for British-born Joanne Rowling, the most staggering successful author in the world. Yet her earlier life was a prologue far removed from her present golden years. She was in Portugal, trapped in a physically and emotionally abusive marriage, mother of an infant, when she fled penniless to her sister’s Scottish home. Had she succumbed to the depression and contemplation of suicide, the world would never have met its beloved, bespectacled wizard.

At the age of eleven, Malala Yousafzai took on the Taliban by giving voice to her dream of obtaining an education. They responded with bullets. In 2014, she became the youngest winner of the Nobel Peace Prize. She stated of her historic win, “I am pretty certain that I am the first recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize who still fights with her younger brothers.”

Although these ladies hail from different climes and chronologies, they share a common denominator. Life had thrust them to their knees, but they refused to remain in that position—with the result they not merely stood, but soared.

I have a connection with one of our era’s great ladies. Gail Devers had been a student at Sweetwater High School in National City, CA where I currently teach. After graduating from UCLA, she was on her way to becoming an Olympic track and field star when smitten with Graves’ disease. The girl who was always running was reduced to crawling, and doctors suggested amputating her feet. Her husband, feeling it was not what he had signed up for, declined to live up to “the in sickness and in health.” An embodiment of true grit, Gail went on to become a three-time Olympic champion.

The parable of the donkey in the well is a metaphor for the power of persistence, of surviving against the proverbial odds. One day an old donkey fell into a well and the farmer decided, as he had outlasted its usefulness, to let him die. He grabbed a shovel and began to toss dirt into the well. At first the cornered animal let out piteous cries followed by silence. Every time the dirt hit his back he shrugged it off; soon he was level with the ground and walked away.

Although this volume showcases the women who left imprints on the face of history, we must remember the unsung women who embody the face of fortitude. A metaphor for these ladies is Mary Tyler Moore tossing her iconic blue-knit beret into the air to the accompaniment of “Love is in the Air”—a thumbs up gesture to life. The freeze frame captures her megawatt smile, a testimony to one can endure bell-bottoms, bad dates, institutionalized sexism, and still retain faith.

Recently I met “Rebecca,” who could have qualified as a contestant on the 1960s television show Queen for a Day. For the younger-than-baby boomer generation, it was the precursor to reality television. Every week it featured four desperate housewives whose criteria for appearing on the air were lives of unmitigated horror. Each contestant turned the show into a public confessional, wherein they would relate their litany of sorrows. Each of the ladies’ faces wore expressions reminiscent of the figure from the painting The Scream. The studio audience would buzz in for the tale of greatest grief and the “winner” would be gifted with tiara, sash, and prize, and pronounced Queen for the Day. When “Queen Rebecca” shared what she was up against—every day a Sisyphus struggle for survival—I marveled how someone could take what her life was dishing out. However, what resonated far more than Rebecca’s pain were her words, “Hell, I’m still here.”

In addition to writing the book as a paean to the ladies who, rather than letting all obstacles smash them, smashed all obstacles, was the fact that historically men seem to have garnered the monopoly on transcending suffering. One needs only to think of the Bible and the men engaged in epic struggles: Jonas adrift in the whale’s belly, Job as the archetypal whipping boy, Christ on his cross. From the modern era are the images of the jailed freedom fighters: Mandela in South African, Gandhi in India, King in America. Their female counterparts have somehow been obscured, although their sufferings were no greater, their courage no less.

The Grimm brothers did not help matters when they portrayed princesses as damsels in distress—unable to save themselves, they depended on the auspices of the prince: to find the glass slipper, to awaken with a kiss, to climb the golden tower of hair. As a little girl, my favorite record was Thumbelina, the enchanting fairy no bigger than a thumb, who, trapped on a lily pad and fearful of the advances of an unwelcome toad, plaintively cried out, “Oh hear, my plea/And rescue me…” Walt Disney, in his early films, perpetuated this stereotype—Snow White sang in her little girl voice, “Someday my prince will come.” His studio later gave feminism some teeth when it made their royal maidens the possessors of backbone. One of these rough and tough ladies was Megara (Meg,) who nailed it when she proclaimed, “I’m a damsel. I’m in distress. I can handle this. Have a nice day!” At the end she overcomes her fear of heights and saves strong-man Hercules. Pixar piggybacked on this with Brave—a film which lives up to its name. Merida, the red-haired archer, is the first animated princess in a major American film who did not fall in love, who refused to get married, and does not depend on a handsome mate to save the day. And, in 2013, we had Frozen’s Elsa, freed by the love of her sister. Unfortunately, Anna accomplished this feat in the stereotypical heroine attire—in revealing dress which showcased a body of anatomically unrealistic proportion and high heels. One icy step forward—one icy step back.

This paradigm shift can partially be attributed to the shoulders’ of the historic women on which we stand: Susan B. Anthony casting a ballot when it was illegal for women to vote, Germaine Greer’s The Female Eunuch, Helen Reddy’s lyric “I Am Woman.” It is females of this intrepid ilk which made for modern heroines who are far from the mythological maidens chained to a rock, helplessly and hopelessly waiting to be devoured by the Minotaur. Thanks to a growing multitude of kick-ass heroines, the damaging damsel in distress paradigm is receding into the Disney distance, a conceit antiquated and unenlightened. These days, our daughters experience gals such as the non-animated archer Katniss Everdeen and other fearless femmes who are holding down the fictional fort and making Princess Poor Me a phenomena of the past. These non-shrinking violets fortunately do so without loss of pheromones. Their anthem is poet Maya Angelou’s own,

Does my sexiness upset you?

Does it come as a surprise

That I dance like I’ve got diamonds

At the meeting of my thighs?

In my inbox I receive emails from friends concerning female empowerment, of the solidarity of sisters. Still I Rise is an extension of these cyber-hugs. By sharing these stories of courage, it is my hope it will give faith to those who falter, for there is truth to the might of the pen. Nelson Mandela, while a prisoner of apartheid on Robben Island, kept in his cell an inspirational poem from 1875, “Invicitus.” It was a kind of Victorian My Way, about one’s head being bloody but unbowed, of remaining captain of one’s soul. The verse from which I took the title of this volume was inspired by the intrepid Maya Angelou, whose life was a patchwork quilt of challenges. She had been the victim of a childhood rape whose trauma left her without a voice for several years, failed marriages, and racism. Yet, through the elixir of words, she broke free from the solitude of silence and became the poet laureate at President Clinton’s inauguration. Through her travails, she discovered why the caged bird sings—it sings because though imprisoned, it never loses the vision of a life free from bars. In an ode to her indomitable spirit, she wrote an anthem of fortitude:

You may write me down in history

With your bitter, twisted lies,

You may tread me in the very dirt

But still, like dust, I’ll rise.

In the following chapters are the stories of intrepid women who, when the going got tough, kept going, which enabled them to cross the finish line. Their lives prove that the possessors of estrogen are not just “the fairer sex” because of outer beauty but inner strength. They refused to let go of Emily Dickinson’s hope is the thing with feathers and subsequently blazed trails. By reading of their power of persistence, their determination that dreams do not just have to remain in the realm of sleep, we can glean succor. Rather than view their sisters as competitors, they became the shoulders on which others can stand. Strong individuals are usually the possessors of uneasy pasts. However, heroines are defined not by their wounds, but by their triumphs. It is my hope that my readers will draw strength from reading of these great ladies’ struggles, and like dust, shall rise.