Читать книгу Still I Rise - Marlene Wagman-Geller - Страница 18

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 4: STEEL GARDENIA (1895)

The Civil Rights timeline has witnessed significant Afrcan-American firsts, each a step closer to Dr. King’s “We shall overcome.” In sports, Althea Gibson competed at Wimbledon in 1951; in music, Marion Anderson sang at the Metropolitan in 1955; in literature, Toni Morrison received the Nobel Prize in 1993. Another woman who succeeded in the proverbial against-all-odds arena was a Southern “belle” whose achievements made for a quilt of the bitter, of the sweet.

After winning the 2010 Oscar for Best Supporting Actress for Precious, Mo’nique stated she was wearing a royal blue dress, along with gardenias in her hair, because Hattie McDaniel had dressed in that fashion seventy years earlier when she had become the first African American to receive an Academy Award. The event was met with shock, as everyone felt her Gone with the Wind co-star Olivia de Havilland was a shoe-in. Mo’nique thanked her predecessor “for enduring all that she had to, so that I would not have to.” Mo’nique’s praise was unequivocal; however, this had not been the case when Hattie had become a card-carrying member of the be-careful-of-what-you-wish-for club.

Hattie McDaniel, who created a tempest in a celluloid teacup, was the youngest of thirteen, born to former slaves in 1895 in Wichita, Kansas. Her father, Henry, had fought for the Union in the Civil War and later became a Baptist minister who moonlighted as a banjo player in minstrel shows. Her mother, Susan, was a gospel singer. While Forest Gump spent every spare moment of his childhood running, Hattie spent hers singing, to such an extent Susan sometimes bribed her with spare change to buy a moment of silence.

In 1901, the family moved to Colorado, where she was one of only two black children in her elementary school; she ended her education in her early teens to join her father’s troupe. It seemed a more palatable path than domestic work, the most likely career path for blacks in the early twentieth century. A natural entertainer, she became popular in the African American theater scene in Denver, and her gift of pantomime led to her reputation as the black Sophie Tucker. Acclaim likewise followed for her sexually suggestive renditions of the blues, many of which she penned. However, even after a nationwide tour of vaudeville houses, McDaniel was often forced to supplement her income with work as a domestic. By age twenty, she was also a widow. Her marriage abruptly ended in 1922 when her husband of three months, George Langford, was reportedly killed by gunfire. The same year her father died and, devastated by the back-to-back losses, she took solace in performing. In 1925, she appeared on Denver’s radio station that garnered her the distinction of being the first African American woman to perform in this medium.

In 1929 her booking organization went bankrupt as a result of the Great Depression, and Hattie found herself stranded in Chicago with no job and meager savings. On a tip from a friend, she departed for Milwaukee and obtained a position at Sam Pick’s Club Madrid as a bathroom attendant. The club engaged only white performers but, an irrepressible singer, she belted out tunes from the restroom, a unique venue for showcasing her talents. Patrons took notice of her voice and good nature, which led the owner to allow her onstage. After her rendition of “St. Lois Blues,” she became a wildly popular attraction. She remained in the club for a year until her siblings Stan and Etta invited her to join them in Los Angeles. Like other Hollywood hopefuls, in Tinseltown she had dreams of becoming what twinkled in the firmament, but finding her way in Hollywood was not easy. Black actors’ choices consisted of: African savage, singing slave, or obsequious employee. Stan was able to throw her a life-preserver, and she found work in the radio show “The Optimistic Do-Nuts.” She earned the nickname Hi-Hat Hattie after showing up in evening attire for her initial broadcast.

Hattie’s long-dreamed of screen debut occurred in 1931 when she played a bit part as a maid, for which she was able to draw on firsthand experience. Her breakthrough was as Marlene Dietrich’s domestic in Blonde Venus, and three years later as Mom Beck in The Little Colonel that starred Shirley Temple and Lionel Barrymore. With her perfect comic timing, she appeared alongside the biggest stars of the silver screen—Clark Gable, Jean Harlow, Henry Fonda. She was so successful that MGM did not allow her to play anything other than as a domestic or to lose an ounce, though she tipped the scale at three hundred pounds. Mammy had to be fat. Firmly typecast as the woman with the apron, she was one of the logical candidates to secure the coveted role of Mammy in David O. Selnick’s 1939 production, Gone with the Wind. The competition for the part was as fierce among black hopefuls as the part of Miss Scarlett was for whites. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt had recommended her own maid for the part; however, Hattie had her own patron—the King of Hollywood, Clark Gable. She nailed the audition when she appeared in a plantation maid uniform and so impressed Selznick he called off other tryouts with the words, “Save your overhead boys. We can start shooting tomorrow.” What further helped was she fit the stereotypical perception of the Southern domestic as she was the doppelganger of Aunt Jemima, which proliferated on Quaker Oats boxes. During the epic film, clad in trademark apron and bandanna, she delivered lines in antebellum lingo: “What gentlemen says and what they thinks is two different things,” “I ain’t noticed Mr. Ashley askin’ for to marry you.” Although cast as the servant, she refused to be subservient. She told Selznick she would not utter a racial epithet or employ the caricature phrase “de Lawd.”

The premiere of Gone with the Wind at the Loew’s Grand Theater was the apogee celebration of 1939, and the night of its premier Atlanta resurrected its plantation past: the women attended in hoop skirts, the men in breeches, and Confederate flags flapped in the Southern breeze. However, absent from the revels were the black performers, as Jim Crow held sway. Clark Gable threatened to boycott the gala unless Hattie was permitted to attend; however, he relented under her insistence he not create a scene. A second salve was a telegram from Margaret Mitchell, the celebrated author of Gone with the Wind, who said of Hattie’s absence from the premier’s festivities, “I wish you could have heard the cheers when the Mayor of Atlanta called for a hand for our Hattie McDaniel.”

If McDaniel’s exclusion from opening night was not enough, she was sharply criticized by blacks who viewed the epic film as a valentine to the slave-owning South and a poison-pen letter to the anti-slavery North. Walter White, head of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, singled her out for reproach, arguing she was an Aunt Tom. She lashed back by asking, “What do you expect me to play? Rhett Butler’s wife?” However, her most memorable comeback: “I’d rather play a maid and make $700 a week than be a maid and make $7.00.” One can only wonder how she would have reacted to the fact that seventy-two years later, Octavia Spencer won an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress for her role in The Help—as a maid. On top of the back-to-back backlash from whites and blacks, Hattie had to deal with the demise of her second marriage to Howard Hickman that both began and ended in 1938.

In 1940, Gone with the Wind garnered ten Academy Awards; predictably Best Actress went to Vivien Leigh; unpredictably, Best Supporting Actress went to Hattie McDaniel, the first time an African American had been honored and an event which was not to occur for another fifty years when Whoopi Goldberg received the tribute for Ghosts. Although the more liberal North allowed her to attend the Hollywood gala at the Ambassador Hotel and personally receive her award, she and her African American escort were seated at a segregated table. In her sixty-seven second emotional acceptance speech, she stated she “hoped to be a credit to her race.” Gossip columnist Louella Parsons for once put down her poisoned pen:

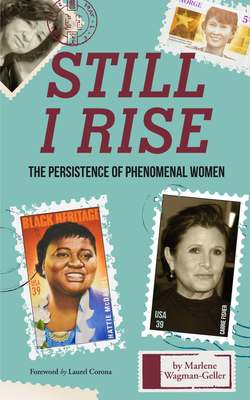

If you had seen her face when she walked up to the platform and took the gold trophy, you would have had the choke in your voice that all of us had when Hattie, hair trimmed with gardenias, face alight, and dressed up to the queen’s taste, accepted the honor in one of the finest speeches ever given on the Academy floor.

Hattie, overcome with emotion, returned to her seat by the kitchen to thunderous applause.

After Gone with the Wind, Hattie suffered a reversal of fortune, partially due to the demise of stereotypical roles. With the advent of World War II, Hollywood came under pressure to portray blacks in a more positive light to encourage their patriotism. As a result, a new black star emerged, Lena Horne, who was everything Hattie McDaniel was not: young, sexy, and not a maid (stipulated in her contract). Turning once more to love to fill the gaping career hole, she married third husband, Lloyd Crawford, in 1941. She was ecstatic when she confided to gossip columnist Hedda Hopper she was expecting a long-awaited baby. With nesting instinct in full gear and wealth from acting, Hattie purchased her dream house in a wealthy enclave in Los Angeles. The white, two-story estate boasted seventeen rooms, decorated in a Chinese theme. She celebrated the purchase with a huge party, where one of the guests was Clark Gable. However, the joy of first-time home ownership came with an expiration date. Her neighbors launched a campaign to evict her on the basis of a white-only ordinance. This time she decided to make a scene. It resulted in a Supreme Court decision that eliminated “restrictive covenants” which had kept African Americans from residing in certain areas. Her joy at the victory was quashed when Hattie discovered the pregnancy was a hysterical one. The truth threw her into a tsunami of depression. On top of that, her marriage ended in 1945, and Hattie cited one reason was her husband had threatened to kill her. Her fourth and final walk to the altar was with Larry Williams, in Yuma, Arizona, that was only of a few months duration.

Hamlet had said when sorrows come they come not in single spies but in battalions, and Hattie had weathered hers: white and black slings, aborted marriages, hysterical pregnancy, curtailed career. However, like dust she rose. She returned to radio, a medium which knew no color, the one where she had reigned as Hi-Hat Hattie. However, after taping several episodes of The Beulah Show, she met the one foe she was not able to overcome. By 1952, she was too ill from breast cancer to work, and died in the hospital situated on the grounds of the Motion Picture House in Woodland Hills. At the church service she received a variation of her Academy ovation when thousands of mourners turned out to celebrate her life and its singular achievement of breaking the color barrier in film.

Through her bequest, her Oscar was given to the predominantly black Howard University for their drama department in remembrance of having honored her with a luncheon after her historic win. It was a small plaque rather than the current gold-plated statue. Mysteriously, it vanished during the 1960s racial unrest, and to this date its whereabouts remains unknown. One theory claims it was tossed by rioting students into the Potomac in protest against racist stereotyping.

Even in death Ms. McDaniel could not escape the long shadow cast by Jim Crow. In her will she had stated, “I desire a white casket and a white shroud; white gardenias in my hair and in my hands, together with a white gardenia blanket and a pillow of red roses. I also wish to be buried in the Hollywood Cemetery.” She had always loved being amongst the stars, and the cemetery held the remains of Rudolph Valentino, Douglas Fairbanks, and other silver screen immortals. Though the flowers, clothing, and casket were fulfilled, her desired final resting place did not come to pass because of its segregationist policy.

Posthumously, the Old South did become a civilization gone with the wind. In 1999, the new owner of the cemetery offered to have Hattie’s remains transferred, though her family declined the offer. Instead she was honored on its grounds with a monument. A further tribute was two stars on Hollywood’s Walk of Fame and her image on a 2006 postage stamp. The latter was fitting, as she had left her stamp on American history. Hattie McDaniel had proved not just a credit to her race, but to the human race, truly a steel gardenia.