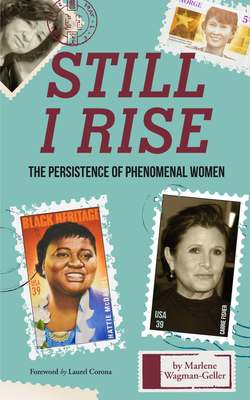

Читать книгу Still I Rise - Marlene Wagman-Geller - Страница 20

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 5: “WHERE YOUR TREASURE IS…” (1903)

In his final days, Frederick Chopin, the supreme poet of the piano, requested his body be interred in his adopted city of Paris while his heart be laid to rest in his native Poland. His organ resides in Warsaw in the Holy Cross Church. Another posthumous act surrounding the composer is he saved a woman’s life, 165 years after his own passing.

Alice—nicknamed Gigi—was born in Prague in what was then Austria-Hungary, the city that served as a cultural and intellectual melting pot of Germans, Czechs, and Jews. She was the fourth of five children, including twin sister Marianne (Mizzi), of Friedrich and Sophie Herz. The German Jewish family had enjoyed a comfortable life through her father’s factory that supplied the Hapsburg Empire with precision scales, but lost most of their wealth in the First World War. Faced with economic deprivation, young Alice said, “And so we realized, as little children, what is war.” Her diminutive height—she was five feet—was a cause of parental concern, and for a while Friedrich paid for her to be stretched in an orthopedic machine. It had no effect—other than to cause pain.

Although money was in short supply, they had something they valued more than materialism: an appreciation for the arts. Sophie had been a childhood friend of the conductor Gustav Mahler and socialized with poet Rainer Maria Rilke. Through the eldest sister Irma’s husband, Felix Weltsch, they were introduced to a reclusive young man who the children called Uncle Franz, author Franz Kafka. The writer once attended their family’s Passover Seder and lent his voice to “Dayenu.” Sometimes he took Alice and Marianne into the woods and entertained them with make believe. Alice recalled, “Stories which I’ve forgot, but I remember the atmosphere. It made a deep impression.” One can imagine. She reminisced about the literary giant that he had “great big eyes” and was “a slightly strange man.” He also once made a comment that she did not understand until much later: “In this world to bring up children—in this world?”

Alice’s magical moment from childhood was when she first sat in front of the piano at age five. Her initial lessons were from Irma, and she played duets with her violinist brother. Her parents, recognizing she was a child prodigy, arranged lessons with Vaclav Stephan, who had studied in Paris with Marguerite Long. For three years she was under the tutelage of Conrad Ansorge, who had been a student of Liszt, a living link she would mention with pleasure almost a century later. “Liszt got a kiss from Beethoven, Ansorge got a kiss from Liszt and I got a kiss from Ansorge!” She also admitted of the latter, “as a pianist, extraordinary, as a teacher, not so good.” This was because he would often absent himself and come back smelling of alcohol, so lessons were arranged first thing in the morning to catch him when sober. Her final instructor was Arthur Schnabel, who told her—after accepting a large fee—her prowess was of a standard that he could not improve. Such was her talent; Alice entered the German Academy of Music and Drama in Prague, headed by Alexander von Zemlinsky, a former pupil of Brahms. Her formal concert debut came at age sixteen—the youngest person to have been so honored—when she performed Chopin’s Concerto in E minor with the Czech Philharmonic to a sold-out hall, eliciting rave reviews. She continued to perform regularly in Prague and also built up a solid roster of private students. Max Brod, Kafka’s publisher, sang her praise. By her late teens, she was performing in concerts throughout Europe.

While music was Alice’s first love, another arrived in 1931 when she met Leopold Sommer, an amateur violinist, who she married a fortnight later. She said that she was bowled over by his compendious knowledge of art and music. At the height of her career, married with son Stephan, her world of privilege began to crumble. Everything changed when Hitler, casually tearing up the Munich Accord of a year earlier, marched his troops into Prague. Alice was in Wenceslas Square on March 13, 1939, watching the invasion, when an open-topped vehicle came past bearing Adolf Hitler, his right arm lifted in the Nazi salute. The anti-Semitic edicts began: Jews were forbidden to perform in public, own telephones, or to purchase sugar, tobacco, or textiles. The Sommer’s neighbor offered to buy these forbidden goods for the family—at double the price. In addition, their movement about the city was restricted, and they were compelled to wear the Star of David. Failure to comply with the latter was to summon execution. Alice was devastated at the hatred, especially as from a young age, she had looked up to Germany, the land of Goethe, Schiller, Bach, and Beethoven. Her sisters and their husbands had bought visas for Palestine and left just prior to the takeover. Alice had decided against immigration as her widowed mother was too frail to travel. The Sommers were allowed to remain in their apartment, Nazi neighbors on every side.

Even worse than the deprivations and the sanctions were the deportations for “resettlement,” where people headed east into oblivion. The SS required Leopold to work for the Jewish Community Organization, where he was given the task of drawing up the names for removal from Czechoslovakia. Because of his mother-in-law’s advanced age, he was eventually required to add the name of Sophie Herz. It was after Alice escorted her sickly, seventy-two-year-old mother—permitted only to bring a small rucksack—to the deportation center that she was at “the lowest point of my life.” Of her mother’s fate she said, “Till now I do not know where she was, till now I do not know where she died, nothing.” She was on the brink of a breakdown when an inner voice urged her to learn Chopin’s Etudes, the set of twenty-seven solo pieces that express the ultimate sorrow and raptures of human existence and are some of the most technically demanding and emotionally impassioned works in piano repertory. The Etudes provided a consuming distraction at the loss of her adored mother and the hovering web of doom that hung over the city’s remaining Jews. She said, “They are very difficult. I thought if I learned to play them, they would save my life.” And so they did.

In 1943, the inevitable came to pass, and Leopold, Alice, and five-year-old Stephan received their deportation notice. Leopold comforted his wife, telling her from his position in the Jewish council he had heard they staged concerts at what the Czechs called Terezin, the Germans called Theresienstadt. She replied, “How bad can it be if we can make music?” Of that horrific time Alice recalled, “The evening before this we were sitting in our flat. I put off the light because I wanted my child to sleep for the last time in his bed. Now came my Czech friends: they came and they took the remaining pictures, carpets, even furniture. They didn’t say anything: we were dead for them, I believe. And at the last moment the Nazi came—his name was Hermann—with his wife. They brought biscuits and he said, ‘Mrs. Sommer, I hope you come back with your family. I don’t know what to say to you. I enjoyed your playing—such wonderful things, I thank you.’ The Nazi was the most human of all.”

Terezin, northwest of Prague, was an eighteenth century garrison town converted into a Jewish ghetto, used as a front for what was in reality Hitler’s ante-chamber for the death camps. It was touted as a “show camp”—“The Fuhrer’s gift to the Jews”—and was advertised as a place where Jews might find a welcome haven. Indeed, a few deluded souls had applied for admission, paying extra for a room with a view. It was used as a propaganda tool for Nazi officials seeking to demonstrate to the Red Cross that European Jewry was not, as rumor had it, mistreated. It had a library, an art studio, and lecture hall—all of which could be used after performing back-breaking labor.

The Sommers arrived in Terezin and found a city of disease, death, and starvation. Upon arrival, she was separated from Leopold, and she and Stephan were herded with one hundred other mothers and children into a freezing room with filthy mattresses spread on the floor. Alice recalled, “We didn’t eat. In the morning we had a black water named coffee, at lunchtime a white water called soup, in the evening a black water called coffee, so my son didn’t grow a millimeter…” The following year, Leopold was forced onto a train; just before departure, he made Alice promise never to volunteer for anything. The advice saved her life: a little later the authorities asked if the ghetto wives wanted to rejoin their husbands, and they climbed into the cattle cars that took them to their deaths. Alice remembered her promise, and she and Stephan remained behind; at the end of the war, he was one of only 123 children to survive, of the 15,000 who had passed through Terezin. Leopold perished in Dachau, probably from typhus, a few weeks before liberation. A fellow prisoner later brought Alice her husband’s battered camp spoon—his only remaining physical memento.

After Leopold’s departure Alice, despite the horror, found the strength to still rise. She had to remain strong for Stephan. Music also helped her, both spiritually and literally. Throughout her two years in Terezin, through the hunger and cold and death all around her, through the loss of mother and husband, Alice was sustained by a Polish man who had died long before—Frederick Chopin. It was that composer, Alice averred, who let her and Stephan survive. She performed at one hundred concerts, playing from memory. What moved her audiences the most were the Etudes.

Terezin had an orchestra, drawn from the ranks of Czechoslovakia’s foremost figures in the performing arts, whose members literally played for time before audiences of prisoners and their Nazi guards. Mrs. Herz-Sommer, who performed on the camp’s broken, out of tune piano, was one of its most revered members. Even though many of the concerts were charades for the Red Cross, she said the healing power of music was no less real. “These concerts, the people are sitting there—old people, desolated and ill—and they came to the concerts, and this music was for them our food. Through making music, we were kept alive.” One night, after a year’s internment, she was stopped by a Nazi officer who told her, “Don’t be afraid. I only want to thank you for your concerts. They have meant much to me. One more thing. You and your little son will not be on any deportations lists. You will stay in Theresienstadt until the war ends.”

After their Russian liberators arrived, Alice and Stephan returned to their former city. “When I came back home it was very, very painful because nobody else came back. Then I realized what Hitler had done,” she stated. A midnight concert she gave on Czech radio was picked up on short-wave in Jerusalem that alerted her family to the fact she was still alive. In 1949, with postwar anti-Semitism still swirling around Prague and with the Communists tightening their grip, Alice and Stephan joined her family in the new nation of Israel. She became a member of the teaching staff at the Jerusalem Conservatory, learnt Hebrew, and performed to audiences that included Golda Meir and Leonard Bernstein. For almost forty years she enjoyed “the best period in my life…I was happy.” Stephan took the name Raphael, and proved himself an exceptionally talented cellist. It was his appointment to a teaching post at the royal Northern College of Music in England that prompted Alice to move to Britain in 1975. There she obtained a flat in London’s Belsize Park, in apartment number 6. Her resilience was tested again in 2001 when Raphael, on a concert tour of Israel, collapsed with a ruptured aorta and died on the operating table. She found solace in her two grandsons, David and Ariel.

Apartment number 6 was dominated by lovely paintings, her Steinway piano; it also included a battered silver spoon. Alice faithfully practiced, and after her advanced age had immobilized one finger on each hand, she reworked her technique so she could play with eight.

In her later years, Alice received acclaim for being the oldest Holocaust survivor, and due to her remarkable life, she became a beacon to journalists. But though her hands were failing, her musical acumen remained sharp. On her one hundred-and-tenth birthday, the New Yorker’s music critic, Alex Ross, called on her. Because Mrs. Herz-Sommer could find journalists wearying, he presented himself as a musician. When she asked Ross to play something, he gamely made his way through some Schubert before Alice stopped him, “Now, tell me your real profession.”

In 1879, Chopin’s heart was interred in Holy Cross behind a memorial slab that bore a citation from the Book of Matthew—and one that could serve as Alice Hertz-Somner’s epitaph, “Where your treasure is, there your heart will be also.”