Читать книгу The Power of Freedom - Mart Laar - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

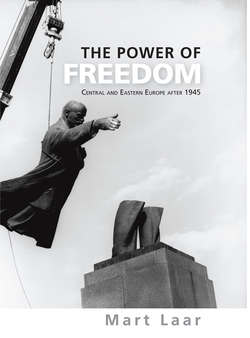

On the other side of the curtain

Back to the shadow: the Communist takeover and the Red Terror

ОглавлениеThe sacrifices made during the Second World War did not bring freedom to Central and Eastern Europe. As Stalin predicted, the social and political systems of the East and West were destined to follow the positions of the occupying army. Military force has in fact been the key to success in almost every Communist takeover in history. Of a total 22 Communist takeovers after 1917, the Red Army played a decisive role in 15 of them, while in the other cases, native Communist military forces were used. In this, the Soviets followed the statements of Lenin, Stalin and Mao according to which ‘political power grows out of the barrel of the gun. Anything can grow out of the barrel of the gun.’38 In fact, looking at the fate of Central and Eastern Europe, it may safely be argued that the transformation of the Central and East European countries into totalitarian Communist states within the span of a few short years could not have been engineered if it had not been for the decisive role played by the Soviet Red Army.

Cemetery of Lithuanian deportees in the Far North of the USSR

Yet the division of Europe was not decided at once. The Soviet Union was weakened and devastated. Stalin had annexed 272,500 square miles of foreign territory and needed time to purge and prepare them for the Soviet way of life. Most importantly, the Soviets did not yet possess the atomic bomb. Lacking this military might, Stalin had to manage the takeover of Central and Eastern Europe with some caution. Unfortunately, the Western democracies did not understand the situation and therefore failed to use the opportunity to force the Soviet Union back to its pre-war borders. Winston Churchill had seen it coming and had warned the West – but to no avail. When he addressed his people after receiving Germany’s surrender, Churchill gave voice to his fears:

On the continent of Europe, we have yet to make sure that the simple and honourable purposes for which we entered the war are not brushed aside or overlooked in the months following our success and that the words freedom, democracy and liberation are not distorted from their true meaning as we have understood them. There would be little use in punishing the Hitlerites for their crimes if law and justice did not rule, and if totalitarian or police governments were to take the place of the German invaders. 39

At this time, however, almost nobody understood him. Thus, Stalin was effectively given free rein to do as he pleased in the conquered territories.

For Stalin, post-war Europe was split into four zones. The territories annexed as a result of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact – the Baltic states, Eastern Poland and Bessarabia – were to be integrated immediately and completely into the empire. In the zone lying to the west of this, which included Poland, Romania and Bulgaria, he wished to install vassal Communist regimes with a minimum transition period, whilst in the zone lying to the west of this, which included Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia, he reckoned on achieving the same goal after an interval of some years. Finally, in the countries of Western Europe proper, he was planning to exert his influence, initially at least, through national Communist parties.40 The Soviet zone in Germany had to stay under direct Soviet control until the fate of the country had been decided. Stalin actually met with the leaders of the German Communist Party as early as 4 June 1945 to lay out plans for incorporating a reunified Germany into Moscow’s sphere of influence. To achieve this, the Red Army would continue to control the Soviet occupation zone, while the German Communists would seek popular support beyond the reach of Soviet military authority. Using Soviet support, the Communists in the East would have to merge with the Social Democrats and from this base, develop contacts with the West German Social Democrats, then bring them over to their camp with the promise of a unified Germany.41 The future of Austria and Finland was unresolved – Stalin did not have anything against the Sovietisation of these countries but understood that it would not be easy. Rather, he seemed to be more interested in gaining control of Iran and Turkey, both of which came under intense Soviet pressure during this period.

Consequently, in the immediate post-war years (1945–1947), Stalin insisted on direct control above all in the Soviet zone of Germany, the Baltics and the other territories he had conquered as a result of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. The main means of control was direct and open terror against the population as a whole, which sought from the beginning to wipe out even the most minor attempts to resist Soviet power. Within its occupation zone, the Soviet police and state security services detained approximately 154,000 Germans and 35,000 foreigners in ten so-called ‘special internment camps’ between 1945–1950.42 A third of these internees – a total of 63,000 people – died in captivity, most of hunger or disease. The Soviets declared that the people interned in these camps were mainly NSDAP (Nazi Party) functionaries but in actual fact, in the infamous Buchenwald camp, for example, only 40–50 % of the detainees were former Nazis. In addition to this, Soviet military tribunals condemned around 35,000 German civilians to long camp sentences in most cases. The majority of verdicts were meted out for ‘crimes’ against the Soviet occupying power according to Paragraph 58 of the criminal code of the Russian Socialist Federal Soviet Republic (RSFSR). Soviet military courts also pronounced at least 1,963 death sentences and no less than 1,201 of these were carried out.43

Polish freedom fighters killed by the NKVD forces

The terror was even more intense in the countries formally integrated into the Soviet Union in 1940; as a result of the Soviet occupation, Estonia lost 25-30 % of its original population in the period between 1940 and 1955. Hundreds of thousands of Estonians were killed, arrested or deported to Siberia. The same happened to the citizens of the other Baltic countries. During the night of 26 March 1949, 20,722 Estonians, 43,230 Latvians and 33,500 Lithuanians were deported to the eastern territories of the Soviet Union. Taimi Kreitsberg, who managed to escape from the deportation officials, recalled as follows:

I lived at my friends’ place until my brothers were arrested, then they did not dare to put me up any more. What could I do, where could I go? I came to Varstu village soviet to notify about myself. There I was arrested immediately. They took me to Antsla security department, where I saw the informer Hillar Roomus. In Antsla they questioned me – the record of the interrogation was written on the table, I had to sit on the floor, under the table. Then they took me to Võru, I was not beaten there, but for three days and nights I was given neither food nor drink. They told me they were not going to kill me, but torture me [until] I betrayed all the bandits. For about a month they dragged me through woods and took me to farms that were owned by the relatives of Forest Brothers, and they sent me in as an instigator to ask for food and shelter while the Chekists themselves waited outside. I told people to drive me away, as I had been sent by the security organs. Finally, they realised that I was of no use to them and handed me over to the Russian soldiers to be raped. I was not even sixteen at that time.

Deportations and massive arrests continued into the 1950s. Altogether, Latvia lost 340,000 and Lithuania, 780,000 people as a result of the deportations or other persecution.44 A large Soviet military garrison and the continued influx of Russian-speaking colonists, who acted like a ‘civilian garrison’, replaced the lost populations. The goal of this migration was to transform the indigenous people of the conquered nation into a minority within their own homeland. In 1989, native Latvians represented only 52 % of the population of their own country. In Estonia, the figure was 62 %. In Lithuania, the situation was better because the colonists sent to that country actually moved to the former area of Eastern Prussia (now Kaliningrad) which, contrary to the original plans, never became part of Lithuania.45

In the other Central and East European countries, so-called ‘people’s democracies’ were established with Soviet-dominated governments which, with assistance from the KGB and its local counterparts, destroyed democratic opposition in the conquered countries. As usual, the first step was open terror against ‘enemies of the state’ whose ranks could include anyone, not only collaborators of former regimes. The goal of such terror was to introduce an atmosphere of absolute fear that sought from the very beginning to destroy any desire to resist Soviet power. This was mostly done in close cooperation with the Soviet security apparatus. In Poland, for example, the Peoples’ Commissariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD) had its own jails and camps. Between 1944–1946, various Soviet units held around 47,000 people, a quarter of them Polish underground fighters. In the spring of 1945, about 15,000 Silesian miners were sent to the mines in the Donetsk area of the USSR. To combat resistance movements, tens of thousands of people were arrested. In the first 10 months of 1947 alone, nearly 33,000 people accused of ‘banditry’ were arrested and 10,500 were sentenced. In order to liquidate the Ukrainian underground units, all Ukrainians from the combat area – 140,000 people – were resettled in the former German territories of Northern and Western Poland.46 During 1944–1945, the courts passed around 8,000 death sentences, 3,100 of which were carried out. This figure probably does not represent the actual number of people executed as in 1944–1946 hundreds of summary executions were carried out on the spot by firing squads.47 Between 1945 and 1950, almost 60,000 individuals were hauled before ‘people’s tribunals’ in Hungary, 27,000 of whom were found guilty, 10,000 given prison sentences and 477 condemned to death, although only 189 were executed.48 In Bulgaria, after the occupation of the country by the Red Army, between 2,000 and 5,000 people were killed intentionally and without any legal basis. In 1944–1945, so-called ‘People’s Courts’ pronounced 9,115 verdicts, with 2,730 people sentenced to death. The first concentration camp began functioning as early as the end of September 1944 in the village of Zeleni Doli. Several such camps were subsequently established. As of September 1951, over 4,500 people were held in these labour camps. Another figure that should be added to the labour camp statistics is that of the forced labour mobilisations and the internment and relocation of families. In 1945-1953, 24,624 people were forcibly relocated or interned.49

Prisoners of war killed by Communist partisans in May 1945 near Lesce in 2008

The same tactics were used even in countries not under the direct control of the Red Army, such as Yugoslavia, where already at an early stage in the war, Communist partisans were fighting not only against the Germans but also against their ‘class enemies’, executing their opponents and those they identified as ‘kulaks’. After the end of the war, terror reached massive proportions. Tens of thousands of members of the civilian population, as well as members of different military units, fought against the Communists and escaped from Yugoslavia to Austria during the last days of the war where they surrendered to British forces. On the Austrian border in Bleiburg, however, British forces did not accept the surrender and forced the refugees back across the border into the hands of the Yugoslavian Communists. These refugees were then subjected to forced marches over long distances under inhumane conditions and any survivors were killed in the series of massacres known as the ‘Bleiburg massacre’. Afterwards, many gravesites were destroyed by explosions, covered in waste or built over. The exact number of victims is not known; most estimates vary between 15,000 and 80,000 unarmed soldiers and civilians.50

The next wave of terror was targeted against the opposition. For example, the democratic opposition in Poland was headed by the Peasant Party whose leader, Stanisław Mikołajczyk, was undermined by the Communists who arrested, tortured and killed members of the wartime resistance, and harassed non-Communist political parties and civil organisations. In a free election, Mikołajczyk would most certainly have won a sweeping victory. However, free elections were repeatedly postponed.51 The absence of an effective Western policy in Poland made it increasingly possible for the NKVD to terrorise the democratic opposition. From 1946 to 1948, military courts sentenced 32,477 people, most of them members of democratic parties for ‘crimes against the state’.52 Only then the elections were held. In order to be sure that the elections would produce the ‘correct’ results, the Polish security apparatus recruited 47 % of the members of the electoral committees as agents.53 In 1947, after the manipulated elections formalised the liquidation of his party, Mikołajczyk escaped abroad and the Communist takeover was complete.

Queues were normal part of Soviet life. Estonia, 1987

In Hungary, the situation was even more complicated for the Communists. They were soundly defeated in the relatively free elections held in November 1944, polling only 17 % of the votes against 57 % for the Smallholders’ (Peasant) Party. The Communist response was to intensify terror and to sponsor the coalition of ‘democratic’ parties against the ‘reactionary’ smallholders. In 1947, the Communists put pressure on the Prime Minister to resign and increased their intimidation of the opposition. In the rigged elections in August, the Leftist bloc polled 60 % of the votes and were then quick to finalise their takeover. The peasants were also a problem for the Communists in Bulgaria where their main opponent was the Agrarian party. Even when the Communists could control the government thanks to Soviet pressure, opposition to them was loud and active. Unfortunately, it did not receive any real support from the West. Understanding this, the Communists arrested the leader of the parliamentary opposition, Nikola Petkov, in 1947, sentenced him to death and subsequently executed him. The Agrarian Union, with its 150,000 members, was banned and many of its activists arrested. After the destruction of Petkov, the Communists moved quickly to consolidate a full takeover, passing the new ‘Stalinist’ constitution and liquidating the last signs of democracy.

The Communists also had a difficult start in Romania. There, the inter-war political elite had removed the regime of Marshal Ion Antonescu in August 1944, moving back to democracy and suing for peace at the United Nations. Consequently, when Soviet troops entered Bucharest, they found working democratic institutions there. But this did not stop Stalin. Taking advantage of the naiveté of their Western Allies, the Soviet representatives succeeded in gaining strong representation for the Communists in the government, who then undermined the authority of democratic parties and institutions and ultimately gained full control of the government. King Michael tried to resist but no help was forthcoming from the West. After the fraudulent elections of 1947, the Communists gained full control in Romania and the king was forced to leave.

In Germany, the Communists experienced only partial success. With the help of the Soviet authorities, the Red Army and the Soviet secret police worked together to destroy any attempts to resist Sovietisation; the Communists were quick to assert their control over the Soviet zone of occupation. The leaders of the non-Communist political parties disappeared into the NKVD torture chambers, with some of them even being kidnapped from West Berlin. One card that Stalin intended to play in Germany was that of German nationalism. To convince the Germans in the East and West, he was even ready to rehabilitate the Nazis in Germany. As Molotov recalled, ‘he saw how Hitler managed to organise [the] German people. Hitler led his people, and we felt it in the way the Germans fought during the war.’ In January 1947, Stalin asked the German Communists, ‘are there many Nazi elements in Germany?’ And advised them to supplant the policy of elimination of Nazi collaborators ‘[with] a different one – aimed [at attracting] them’. The former Nazi activists should, he considered, be allowed to organise their own party, one which would operate in the same block as the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED) and which would even have its own newspaper. ‘There were ten million members in the Nazi Party overall and they all had families, friends and acquaintances. This is a big number. How long should we ignore their concerns?’ Stalin asked.54 However, Stalin’s attempts to create an anti-Western balance in German politics failed. Memories of Soviet atrocities and the destruction of the country were too fresh, leading Germans outside the Soviet occupation zone decisively to reject all Communist takeover attempts. In elections to the Berlin City Council, pro-Communist forces were soundly defeated. It became increasingly clear that Communist authority relied solely on the bayonets of the Red Army. Ultimately then, Stalin had to give up his hopes of a united Germany allied against the West and accept instead the establishment of a socialist state in the Eastern part of Germany in 1949.55 The formation of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) coincided with the complete rehabilitation of the former Nazis as well as the officers of the Wehramacht in the Soviet occupation zone.56

Czechoslovakia was the last country to fall victim to Communism in Central and Eastern Europe. For some time, it looked as though the country might be able to continue its democratic development. There was no Red Army on Czechoslovakian soil and it was also the only Central European country in which the Soviets accepted the return of the former president. After the war, President Beneš still seemed to be in charge of affairs. At the same time, Soviet prestige was high and the Communists were popular. In the elections held in 1946, the Communists polled 38 % of the votes and proceeded to build coalitions with other parties in the government. By exercising control in the government, the police and the army, the Communists consolidated their influence within the country. In July 1947, Moscow demanded in the most brutal way that Czechoslovakia change its decision to accept Marshall Aid from America. The Foreign Minister, Jan Masaryk, the son of the founder of the Czechoslovakian Republic, likened the decision to a second Munich. This decreased the popularity of the Communists, with public polls demonstrating that their popularity had fallen to 25 %. Now the Communists started to arm their supporters, moving in the direction of a full takeover of power. The Soviet Deputy Minister, Zorin, declared that Moscow would not allow any Western interference, while at the same time Soviet units were concentrated on Czechoslovakia’s borders. President Beneš, fearing civil war and Soviet intervention, accepted the Communists’ demands for a new administration. The Foreign Minister, Jan Masaryk fell to his death from his office window, having almost certainly been pushed by a Communist mob. Beneš resigned and Czechoslovakia was thereafter firmly embedded in the Soviet camp.57

Czechoslovakia’s fate demonstrates that it is not fair to blame the Red Army alone for the collapse of democracy in Central and Eastern Europe. An important part in this was also played by the naiveté and ignorance of Western democracies concerning events in Central and Eastern Europe, and the weakness of the democratic traditions and democratic political parties in that region. The states and societies of Central and Eastern Europe were often poorly integrated, there were segments of society with no commitment to the state; civil society and political competition were weak and often the population had become habituated to authoritarianism and state interventionism. These factors were exacerbated by the impact of the war and Nazi terror, which destroyed the cornerstones of society as most former leading politicians were forced into exile or killed. In this situation it was easy for the Communists to present themselves as the only effective force capable of filling the power vacuum. According to George Schöpflin, the non-Communist politicians were also part of the failure. Schöpflin writes that ‘they were indeed victims, but they contributed to their own marginalisation knowingly and, to a greater extent, unknowingly’.58 They lacked political skills and were too uncertain to summon the determination to face down the Communists. They tended to see the Soviet occupation as a definitive and incalculable constraint in the face of which they were helpless. It is possible that even stronger opposition to Communism would have ended in the same way; nevertheless, the flaws of the non-Communist opposition made the Communist’s triumph easier than it might otherwise have been, breaking, as it did, something in people’s souls. Schöpflin also asks why a surprisingly large part of the population was prepared to cooperate with the Communists in the 1940s, hinting at the rapid growth in the membership of Central and Eastern European Communist parties after the Second World War. It can be linked to the use of nationalist, anti-German feelings and growing radicalisation. The Communists also opened the way for the new ‘elites’ to emerge, supporting the development of a large state bureaucracy. The number of administrators in Poland, for example, increased from 172,000 before the war to 362,400 in 1955.

Prison for political prisoners in Sighet, Romania

At the same time, it is often forgotten that there were at least two other countries that almost suffered the same fate at Stalin’s hands as the countries of Central and Eastern Europe; namely, Austria and Finland. What saved these countries from Communist domination has not yet been the subject of sufficient research – what is clear, however, is that it was not Stalin’s kindness. Stalin was furious when pro-Communist forces were defeated in the Austrian post-war elections in 1945. In Finland, his goal was first, to push pro-Communist forces into the government and then to move towards a takeover, although these plans ultimately failed. There were in fact several reasons why Austria and Finland were saved. One of them was that Finland was defeated in the Second World War but not conquered. Even though the Soviet presence was symbolised by their control of the Porkkala military base and by the Allied Control Commission run by the Soviet representative, Andrei Zhdanov, the Finnish army was clearly still in charge. Within society, there was a strong will to resist any Soviet takeover. In order to prepare for a possible partisan war against the Soviets, nationalist activists hid large amounts of weapons in special stores. The Finnish democratic system had survived the war, political parties were strong and organised, and the Social Democrats were capable of resisting Communist attempts to gain control over the trade unions. In 1948, Stalin nevertheless tried to force Finland onto the same route as Czechoslovakia. In February 1948, at the same time as Czechoslovakia’s fate was being sealed, Stalin demanded that Finland send a delegation to Moscow to conclude a ‘dependence’ pact similar to those he had signed with the new satellites. To make matters worse, the Norwegian foreign minister also received warnings that a Soviet request for a similar kind of treaty might be forthcoming. A month earlier, Stalin had expressed regret to visitors that he had not occupied Finland after the war out of ‘too much regard for the Americans.’ Now he seemed intent on rectifying that mistake, allowing the prominent Finnish Communist, Hertta Kuusinen, to declare publicly that Czechoslovakia’s road ‘must be our road.’59 But when the Finnish Communists tried to use the same tactics that had worked so well in Czechoslovakia, they found President Paasikivi to be very different to President Beneš. Paasikivi concentrated his armed forces on the capital and united all the political parties against the Communists. Any attempt at a takeover failed before it had even started and the Communists were heavily defeated in the next parliamentary elections.60 In Austria, the presence of Western forces played a significant role in undermining Soviet efforts, as did the strength of the Austrian Social Democrats, who crushed the Communists’ attempts to take over the Austrian trade unions. As a result, the so-called ‘October strikes’ organised by the Communists in 1950 failed and the Soviet leaders had to reject the Austrian Communists’ proposal to divide Austria into two parts, as had been done in Germany. Austrian democracy proved to be stronger than Communist pressure.

The loss of Austria and Finland did not, however, trouble Stalin too greatly – he had enough work to do to accomplish his new Communist world system. On the orders of the Kremlin in 1947–1948, Central and Eastern Europe entered a new Stalinist phase that lasted until 1953. All pretences were discarded as Central and Eastern European countries were pushed into outright Sovietisation. Within a few years, all Central and Eastern European countries were forced to accept the political system then prevalent in the USSR. Institutional and ideological uniformity was demanded. All chinks in the armour of the Iron Curtain were to be sealed against Western influence. The Communists took power into their own hands. Pluralism and the last vestiges of democracy vanished. The independent press and public organisations were closed down and civil society was abolished. All the main features of Stalinism were to be ruthlessly enforced wherever they did not already exist. The only feature of pre-war democracy that survived in Central Europe was the empty shell of the multi-party system – completely controlled by the Communists, of course.

The most obvious sign of Stalinism was the intensification of terror. This was manifested in an ongoing series of public and secret trials that adjudicated allegations of economic sabotage by former underground leaders in Poland and the ‘White Legion’ in Czechoslovakia. In the 1950s, for example, 244 people were executed on political charges in Czechoslovakia and a further 8,500 died as a result of torture or in prison. A minimum of 100,000 people were imprisoned for acts against the Communist state between 1948 and 1956. In Poland, repression affected no less than 350,000 to 400,000 people in the period leading up to 1956. Military courts alone sentenced 70,097 people for ‘crimes against the state’ between 1944 and 1953. Some 20,000 prisoners died due to the extremely harsh conditions.61 In Romania, five massive arrest campaigns were launched in 1947, targeting opposition party sympathisers and supporters. More than 100,000 people were to become victims of these actions. The leaders of opposition parties were arrested and condemned for ‘national treason’. The families of arrested persons were deprived of the most elementary means of survival and deported or administratively confined. In 1951, 417,916 people were kept under surveillance, 5,401 of whom were arrested for ‘hostile activity’.62 In East Germany, a new wave of repression was connected with the establishment of the German Democratic Republic. As a result of the dissolution of Soviet internment camps, around 5,000 people condemned by Soviet military tribunals were released and 10,000 ended up in East German prisons. A greater wave of political arrests took place between 1952 and 1953 as a result of the ‘intensification of the class struggle.’

The growing number of arrests throughout the region resulted in the establishment of a system of concentration camps. In the early 1950s, there were 422 concentration camps in Czechoslovakia63 in which people were held under gruesome conditions. In 1950, the number of prisoners in such camps amounted to 32,638 men and women. Zbigniew Brzezinski identified 199 in Hungary and 97 in Poland. Many Central and Eastern European people were arrested by the Soviet authorities, interrogated, sentenced in the Soviet Union and sent to the GULAG. Some Central and Eastern European countries had their own ‘Siberia’ as well: the Danube-Black Sea Canal project in Romania employed prisoners and deported persons; in Poland, special units made up of political prisoners mined the most deadly coal shafts in Silesia; in Czechoslovakia, prisoners were sent to work in uranium mines – in December 1953, the number of people working there reached 16,100.64

Another typical feature of Stalinism were the purges of the Communist parties in the conquered countries; the most violent of these took place in Bulgaria, Hungary and Czechoslovakia. According to Brzezinski, an average of one out of every four party members was purged in each of the East European parties.65 In Bulgaria, for example, nearly 100,00 °Communist Party members were under investigation between 1948 and 1953; many were imprisoned and some executed. Such purges were also organised in the Soviet Union’s ‘new territories’. In Estonia, a campaign was launched against the ‘bourgeois nationalists’ in 1950-1951; a number of leading Estonian Communists were removed from their positions and several of them were arrested and sent to the Siberian prison camps. The campaign also hit cultural circles. Most of the members of the Academy of Sciences were dismissed and creative unions underwent serious ‘clean-ups’. Repression was so severe that almost no new Estonian literature appeared from 1950 to 1952.66

In addition to rank-and-file member purges, prominent Communists were also purged and some of them were subjected to public show trials. One of Stalin’s trustees in the region, the Bulgarian leader Gheorghi Dimitrov, announced, ‘it doesn’t matter what someone’s services and merits might have been in the past. We shall expel from the party and punish anyone who deserves it, no matter who he might have been once upon a time.’ The show trials were mostly instigated and sometimes orchestrated by the Kremlin or even Stalin himself, as they had been in the earlier Moscow Trials. These high-ranking party show trials included those of Koçi Xoxe in Albania and Traicho Kostov in Bulgaria, who were purged, arrested and executed. In Romania, Lucreţiu Pătrăşcanu, Ana Pauker and Vasile Luca were arrested and Pătrăşcanu later executed. Stalin’s NKVD emissary coordinated with the Hungarian General Secretary Mátyás Rákosi in order to determine how the show trial of the Hungarian Foreign Minister László Rajk, who was later executed, should play out. The Rajk trials led Moscow to warn Czechoslovakia’s parties that enemy agents had penetrated high into the party ranks and when the puzzled Czech Communist leaders Rudolf Slánský and Klement Gottwald enquired as to what they could do, Stalin’s NKVD agents arrived to help prepare trials. The Czechoslovakian party subsequently arrested Slánský himself, Vladimír Clementis, Ladislav Novomeský and Gustáv Husák. Slánský and eleven others were convicted of being ‘Trotskyist-Zionist-Titoist-bourgeois-nationalist traitors’ in one series of show trials, after which they were executed and their ashes mixed with material being used to fill roads on the outskirts of Prague. After the trials, the property of the victims was sold off cheaply to surviving prominent individuals; the wife of a future leader of the party, Antonín Novotný, bought Clementis’ china and bedclothes. The Soviets generally directed show trial methods throughout the Eastern Bloc, including a procedure whereby any means could be used to extract confessions and evidence from leading witnesses, including threats to torture the witnesses’ wives and children. Generally, the higher the rank of the party member, the harsher the torture that was inflicted upon him. In the case of the show trial of the Hungarian Interior Minister János Kádár, who one year earlier had attempted to force a confession out of Rajk in his show trial, he was badly beaten and then ‘two henchmen pried Kádár’s teeth apart, and the colonel, negligently, as if this were the most natural thing in the world, urinated into his mouth’. As in Moscow in 1937, the trials were ‘shows’, with each participant having to learn a script and conduct repeated rehearsals before the performance. In the Slánský trial, when the judge skipped one of the scripted questions, the better-rehearsed Slánský answered the one which should have been asked. Some years earlier, most of the people now on trial had themselves eliminated their political opponents and tortured and killed people; they therefore knew exactly what awaited them. This made them ready to play their ‘roles’ in the trials. The only exception was the popular Bulgarian Communist, Kostov, who retracted his confession and refused to admit his guilt. The public broadcast went silent and the trial was finished without Kostov. In Poland, Romania and the GDR, where the Communist parties were less well established, the purges were less severe.67

Stalin used Yugoslavia, where the local Communists had split with Moscow and gone their own way, as an excuse for the purges. Even though some tensions were felt between Moscow and the independent-minded Yugoslavian partisan leaders during the initial years of the Second World War, Tito was a good pupil of Stalin’s in the immediate aftermath of the Communist takeover. The Soviets took the Yugoslavian economy under control, pressing Yugoslavia to sell goods to the Soviet Union at low prices which might, in an open market, have fetched high prices in hard currencies. Moscow, in its assumption of economic and cultural dominance, and in its efforts to infiltrate its agents into the Yugoslavian Communist Party, assumed that it should treat Yugoslavia no differently from the other satellite countries.68 It was wrong. The Yugoslavian leaders felt themselves to be strong; they did not need the Soviet Union to stay in power and were not ready to buckle to Soviet authority. Soviet-Yugoslavian relations deteriorated quickly and in 1948, the Yugoslavian Communist Party was expelled from the Cominform. Stalin ordered his satellite countries to start preparations for the military invasion of Yugoslavia. The assumption in Moscow was that once it was known that he had lost Soviet approval, Tito would collapse; ‘I will shake my little finger and there will be no more Tito,’ Stalin remarked. However, as Khrushchev was reported to have said afterwards, ‘Stalin could shake his finger or any other part of his anatomy he liked, but it made no difference to Tito.’ Tito quickly eradicated any Soviet-supported opposition in his party, arresting and executing many of them and interning thousands of people in a fearsome concentration camp established on the island of Goli Otok. Tito turned for help to Western powers who were immediately ready to include Yugoslavia in their assistance programmes. As Stalin’s attempts to bring down Tito repeatedly ended in failure, the Soviet-Yugoslavia split became a heavy blow to Stalin’s authority.69

In order to combat the Western conspiracy and ‘Titoism’, all spheres of public and, as far as was possible, individual life had to be brought under the control of the Communist party and the secret police. Civic and political liberties were abolished, church and religion suppressed. For the Communists, the Church was one of the major obstacles to the imposition of the Soviet model and so its influence had to be eradicated.70 Some churches were actually more equal than others, in particular the Russian Orthodox Church that had been purged by Stalin decades earlier and brought under absolute control. At the same time, the most active measures were taken against the Uniate Church and Constantinople Orthodox churches. The Uniate Church was totally abolished in Ukraine and suppressed with particular force in Romania. Any priests or bishops who refused to sign their acceptance of a merger with the Orthodox Church were arrested and some of them were gunned down.71 In 1948, the Communist regime passed a law pushing for the dissolution of the Eastern-Rite Catholic Church. In Bulgaria, the first purge of the Orthodox Church came in 1948, when the head of the church was forced to retire into ‘voluntary exile’. In 1949, representatives of the Evangelist Church were sentenced to life imprisonment, while in 1952, several trials were held against ‘agents from the Vatican’, with many Catholic priests being imprisoned and four of them executed.72

The Catholic Church was also actively persecuted in Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary. The Communists’ strategy was simple: first, break down the Church’s institutional network and cut its lifeline to Rome, then undermine its control through a combination of legal restrictions and infiltration of whatever remained. In Czechoslovakia, Archbishop Josef Beran, one of the leaders of the anti-Nazi resistance who had survived three years in Nazi concentration camps, and all the other bishops in the country were interned or imprisoned. Religious seminars were closed and orders banned, the Church’s schools were closed and its land holdings confiscated.73 In Poland in 1953, the Communists went so far as to confer upon the state the authority to appoint and remove both priests and bishops. Cardinal Primate Wyszyński refused to obey and protested the order, which led to his arrest. By the end of 1955, over 2,00 °Catholic activists, among them 8 bishops and 900 priests, were imprisoned.74 The same also happened in Hungary, where leaders of the Catholic Church were imprisoned. The 58-year old Cardinal-Primate of Hungary, József Mindszenty, has recalled how he was tortured by the Communists:

‘The tormentor raged, roared and in response to my silence took the instruments of torture into his hands. This time he held a truncheon in one hand, a long sharp knife in the other. And then he drove me like a horse, forcing me to trot and gallop. The truncheon lashed down on my back repeatedly – for some time without a pause. Then we stood still and he brutally threatened: “I’ll kill you, by morning I’ll tear you to pieces and throw the remains of your corpse to the dogs or into the canal. We are the masters here now”. 75

All aspects of cultural life were also brought under strict control and subject to censorship. The only official model of art – literature, painting and sculpture – was that which conformed to the Marxist canon. Artists of that period were obliged to follow the rules of socialist realism. ‘Decadent’ Western culture was prohibited, as was jazz or rock music. Intellectuals were closely scrutinised and controlled by the secret police, and each work of art was evaluated and censored on the basis of its compliance with the official canon. Just as in Nazi Germany, works deemed ‘inappropriate’ were either destroyed – books were burned or pulped, as paper was valuable – or their distribution was forbidden. All media were subjected to such a high level of censorship that they were reduced to a position from which they could only reinforce the power of the Communist Party.

Following the Soviet example, enforced collectivisation of agriculture was introduced across Central and Eastern Europe, with the sole exception of Yugoslavia. As free peasants resisted collectivisation, open terror was needed to ‘convince’ the farmers to join collective farms. In 1949, collectivsation was enforced in the Baltic countries in the wake of major deportations. The results for agriculture were disastrous. In Estonia, for example, agricultural production decreased by 9.3 % between 1951 and 1955, in comparison with the relatively modest results of 1946–1950. By 1955, the average grain yield had fallen to nearly half the pre-war level.76 Productivity in agriculture actually decreased in all of the countries that had fallen under the shadow of forced collectivisation. Here, Stalin had to learn from his own sad experience. The forced collectivisation of agriculture had had catastrophic results for the Soviet Union, turning Russia from an exporter into one of largest importers of food. As a result of forced collectivisation over the decade between 1928 and 1938, the productivity of Soviet agriculture fell by 25 % in comparison with the ‘inertia scenario’ in which nothing had changed. The grain harvest did not reach 1925-1929 levels again until 1950-1954. Nothing like this had ever happened in the history of modern economic growth77 (Table 2).

But Stalin did not want to learn. For him, collectivisation was needed not for the economy but for politics – private property was one of the archenemies of the Soviet system. Thus, collectivisation had to be carried out regardless of the costs. In Romania, resistance to collectivisation ended in 1949 with the arrest of some 80,000 peasants, 30,000 of whom were tried in public.78 In Hungary, the first serious attempt at collectivisation was undertaken in July 1948. Both economic and direct police pressure were used to coerce peasants into joining cooperatives, but large numbers opted instead to leave their villages. In the early 1950s, only a quarter of peasants had agreed to join cooperatives. By 1953, between 3 and 3.5 million hectares of arable land were uncultivated and 400,000 peasants had been fined. In Czechoslovakia, farms started to be collectivised more intensively after the Communist takeover in 1948, mostly under the threat of sanctions. The most obstinate farmers were persecuted and imprisoned. Many early cooperatives collapsed and were recreated again. Their productivity was low because they failed to provide adequate compensation for the work, moreover, they failed to create a sense of collective ownership; small-scale pilfering was common and food became scarce. Poland too saw active resistance to collectivisation, where it developed very slowly.79 In 1952, a collectivisation campaign was launched in East Germany, leading to the collapse of agriculture and a massive exodus of farmers to West Germany. From January 1951 to April 1953, almost half a million people left East Germany. The farmers who remained were disinclined to do more than produce for their own needs because fixed procurement prices meant little profit. Thus, by the summer of 1953, East German agriculture had entered a real crisis necessitating extraordinary help from the Soviet Union (Table 3).

The situation was no better in other sectors of the economy that were first nationalised and then mismanaged. Under Soviet influence, totally unrealistic goals were set – among them ‘catching up and overtaking’ the developed capitalist states in per capita performance in all of the major production lines over a short period of time. The Soviet leadership demanded that the Central and Eastern European countries shift the orientation and structure of their production and export trade toward the East; a rapid increase in the output of heavy industry and massive deliveries of its products to other socialist countries, the USSR in particular. The result was that these countries started to build up certain industries, even when they lacked the necessary resources and materials to do so. For example, an aluminium smelting plant at Zvornik in Yugoslavia was proudly displayed as the largest in Europe, yet it never made a cent of profit. The expansion of heavy industry was pushed at the expense of the development of all other productive and non-productive sectors of the economy, such as agriculture or light industry. The result was the growing inefficiency of production, the failure to modernise production technology and a drop in the effectiveness of foreign trade. People were subjected to a depressed rate of growth in the standard of living, mounting shortages of goods and insufficient service facilities. ‘We have really screwed up, everybody hates us,’ the young Budapest police chief, Kopacsi, was told by an older Communist comrade on his return to his home town in the early 1950s.80

Table 2

Source: Calculations based on data in B. R. Mitchell, International History Statistics: Europe 1750–1993 (London: Macmillian Reference 1998); B. R. Mitchell, International History Statistics: The Americas 1750–1993 (London: Macmillian Reference 1998); B. R. Mitchell, International History Statistics: Africa, Asia & Oceania 1750–1993 (London: Macmillian Reference 1998); UN Food and Agriculture Organization, FAOSTAT data, 2004.

Table 3

Sources: Wädekin 1982. 85-86; Sanders 1958, 72, 81, 99, 105, 145, 147; Hoffmak and Neal 1962, 273.

In sum, we can conclude that Stalinism in Central and Eastern Europe was a complete failure. Robin Okey argues that Stalinism bequeathed Communist regimes a kind of original sin that might be overlooked, even forgotten in subsequent periods, but which told powerfully against the Communists in the events of 1989. It was not so much the Communists’ monopolisation of power that shocked the captive nations – they had seen this before – but the magnitude and brutality of the terror and the destruction of the previous way of life – and all this for the benefit of another state, the Soviet Union. There is much evidence that contemporaries considered their opposition to Stalinism fundamentally to be a moral one. The violent contrast between words and deeds shocked even those who had supported Communism at the outset. Through its flagrant violation of the basic norms of humanity, Stalinism not only reinforced negative assumptions about Communism but scuppered indefinitely the Communists’ chances of eventually turning a system based on force into one based on conviction.81

38

Legters 1992, p. 3.

39

Churchill 1953, pp. 549–550.

40

Lundestad 1998, pp. 435–450.

41

Gaddis 1997, p. 116.

42

A Handbook of the Communist Security Apparatus in East Central Europe 1944-1989. Institute of National Remembrance. Warsaw 2005, p. 203.

43

Handbook 2005, p. 208.

44

Kukk 2007.

45

Misiunas and Taagepera 1983.

46

Handbook 2005, p. 263.

47

Handbook 2005, p. 273.

48

Romsics 1999, p. 227.

49

Handbook 2005, pp. 74–75.

50

Corsellis and Ferrar 2005.

51

Paczkowski 2003, pp. 146–197.

52

Handbook 2005, p. 271.

53

Handbook 2005, p. 255.

54

Zubok 2007, pp. 70–71.

55

Adomeit 1998, pp. 57–87.

56

Zubok 2007, p. 71.

57

Mastny 1996, pp. 41–42.

58

Schöpflin 1993, pp. 70–71.

59

Mastny 1996, pp. 42–43.

60

Seppinen 2008.

61

Handbook 2005, pp. 34, 271–273.

62

Handbook 2005, p. 305.

63

Handbook 2005, p. 133.

64

Handbook 2005, pp. 136–137.

65

Brzezinski 1961, pp. 91-97.

66

Estonia since 1944 2009, pp. 113–151.

67

Crampton 1997, pp. 261-266.

68

Gyorgy and Rakowska-Harmstone 1979, pp. 213-244.

69

Mastny, pp. 30-40; Crampton, pp. 247-261.

70

Weigel 1992.

71

Handbook, p. 306.

72

Handbook, p. 73.

73

Weigel 1992, pp. 166-170.

74

Kemp-Welch 2008, pp. 44-46.

75

Weigel 1992, p. 222.

76

Misiunas, Taagepera 1993, pp. 156-170.

77

Gaidar 2007, p. 83.

78

Handbook, p. 305.

79

Janos 2000, pp. 248-249.

80

Kopácsi 1989, pp. 112-113.

81

Okey 2004, pp. 11-23.