Читать книгу The Power of Freedom - Mart Laar - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

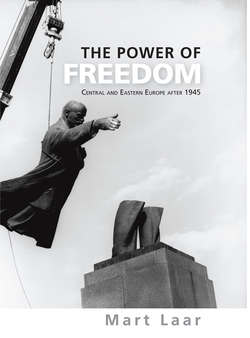

On the other side of the curtain

Usual Communism

ОглавлениеAfter the death of Stalin in 1953 and the ‘thaw’ that began thereafter, open terror in the Soviet Union and its satellite states subsided. Within the USSR, most of the people who had been imprisoned in the GULAG were released, while those who had been deported received permission to return home. In Central and Eastern Europe too, many political prisoners were released. These changes in the Communist system were, however, cosmetic at best as the essence of the Communist dictatorship remained unchanged. The open terror and purges had created a pervasive fear that lasted for decades even though mass terror ceased. It had been very effective: the arrests and other types of repression served as a permanent reminder of who was actually in charge. The Communist system relied on a powerful security apparatus whose role expanded rather than diminished with the end of open terror. To keep the situation under control, even the slightest symptoms of resistance had to be suppressed; in order to exercise control over ever-increasing areas of life, the number of functionaries in the Communist security services grew constantly, with the network of agents expanding simultaneously. The network of agents grew by an annual average of 30 % during the last decade of Communist power in Poland alone, reaching its record level of around 98,000 in 1988. The largest security service was created in Eastern Germany, where the ‘Stasi’ (Staatssicherheitdienst) had 91,015 full-time employees by 1989: one employee for every 180 East German citizens, a proportion that far outnumbered the ratio achieved by the state security service of any other Communist country. At the same time, the Stasi had 174,000 ‘unofficial informers’ on its payroll.82 Eventually, increasingly advanced technical means were introduced. The attempt to exert absolute control over every aspect of human life is excellently portrayed by the Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck film, The Lives of Others.

In this way, then, arrests and repression also continued into post-Stalinist times. In Czechoslovakia, historian Karel Kaplan estimates that a total of ‘about two million Czechoslovak citizens, or half a million families,’ were affected by political persecution under the Communist regime; most often in the form of political purges, exclusion from public life, exclusion from certain professional activities or studies, surveillance by the secret police, review of pensions or forced removal to another place. At the beginning of the 1990s, the Czechoslovakian courts rehabilitated 257,902 people who had been convicted of offences of a political nature.83 The East German state security services conducted 88,718 preliminary proceedings between 1950 and 1989, with most of these resulting in convictions and subsequent imprisonment. The East German courts were responsible for at least 52 death sentences for political offences between 1945 and 1989.84 In 1961, the number of political prisoners in Bulgaria totalled 1,38385, while the number of people imprisoned in Bulgarian labour camps between 1944 and 1962, was 23,531. As was often demonstrated, the Communist authorities did not hesitate to use the army against the people, executing political enemies at home or abroad. In 1978, agents of the Bulgarian Secret Service, with ‘technical help’ from the KGB, killed the well-known dissident and writer Georgi Markov in London.86

The situation was even worse in the Soviet Union where people did not have the small liberties possessed by the inhabitants of the satellite states. The Soviet Union tried to shut itself off completely from the rest of the world. The powerful KGB, with its huge security apparatus and network of informers, controlled all aspects of society. According to Western estimates, the KGB had 720,000 agents on its payroll, the KGB and the Ministry of the Interior (MVD) together had 570,000 officers and men in military formations under their command, including several divisions of border and internal security troops.87 Even though the number of people convicted of anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda – 3,488 between 1958 and 1966 – was not comparable with the figures reached during Stalin’s times, this was only as a result of ‘prophylactic work’; the secret police let potential dissidents know that they were aware of their activities and that they faced a choice of either going to prison or staying silent. Sixty-three thousand, one hundred people received such warnings between 1971 and 1974 alone. There were occasions too when the Soviet leaders demonstrated that they were capable of using their military might against demonstrators at any time. In 1956, Red Army soldiers were authorised to open fire on demonstrations and in Georgia, soldiers who refused to do so were brought before a tribunal. In Novocherkassk in 1962, riots broke out because of price hikes. Soldiers from the Novocherkassk garrison refused to fire on unarmed strikers. The army troops were therefore deemed unreliable and troops from the Ministry of the Interior who were willing to shoot to kill were sent to replace them. More than 20 people were killed and 116 convicted of involvement in the demonstrations. As a result of these events, however, the Soviet leaders began to fear that other soldiers might refuse to fire on protestors and this led them to issue new orders to the armed forces aimed at limiting the use of firearms in confrontations with demonstrators.88

The use of violence against demonstrators served to remind people that the Communist leaders, although not currently using mass terror against the population, were willing to use it without hesitation if they deemed it necessary. This policy was highly effective. People felt in their bones that mass terror could once again become a reality. Fear in society was absolute, killing attempts to resist and stifling initiative. Richard Pipes was right when he wrote that the terror made it clear to the population that under a regime that had no hesitation in executing innocents, innocence was no guarantee of survival. The best hope of this lay in making oneself as inconspicuous as possible, which meant abandoning any thoughts of independent public activity, indeed, any involvement in public affairs and withdrawing into one’s private world. Once society disintegrated into an agglomeration of human atoms, each fearful of being noticed and concerned exclusively with physical survival, then it ceased to matter what society thought, for the government had the entire sphere of public activity to itself.89

At the same time, it was clear that the end of open terror and some liberalisation was a relief for the captive nations. Some economic and social experiments were tolerated, especially in the satellite countries, resulting in a limited degree of economic recovery and improved standards of living. As a result of this increase in social and economic freedoms, some economies in Central and Eastern Europe demonstrated quite impressive growth after the end of Stalinism. It is interesting to note that during the 1950s, greater freedom was given and more reforms allowed in the countries that had been more active in their resistance to the Communist system. The Hungarians did not achieve freedom in 1956. However, in order to pacify the country, they not only received significant material aid from the Soviet Union but also license to launch a set of reforms that paved the way for so-called ‘Goulash Communism’.90 Inside the Soviet Union itself, the Baltic countries were known as the most negative towards the Soviet system and this was most probably one reason for their special treatment. The Soviet leaders tried to turn the Baltics into a shop window to the West, tolerating more economic reforms in these countries than in other places in the Soviet Union. This economic development was not, however, attributable so much to economic reforms as to cheap energy and raw materials imported from the Soviet Union. The discovery of oil deposits in Western Siberia in the 1960s helped the Soviet Union to support the satellite countries more effectively and at the same time earn the hard currency needed to pay for food imports through oil exports to the West. The need for hard currency prompted the use of methods that produced quick results but which risked creating lower yields in subsequent years.91

A shopping trip yields some valuable booty – toilet paper. Poland, 1971

In fact, maintaining the empire became increasingly costly for the Soviet Union with each passing decade. The Soviet economy simply could not afford to retain the satellite states, but the Soviet leaders ignored all the warning signs. Central and Eastern Europe did not help to increase Soviet security; in fact, it created more problems than it solved. In order to preserve internal cohesion and the stability of the Communist bloc, the Soviet Union had to keep 585,000 troops stationed in the Central and Eastern European countries and 1.4 million along its Western borders. To sustain the Communists’ hold on power, the Soviet Union had to subsidise the Central and Eastern European economies, particularly important in view of the regular insurrections against Communism. The Soviet Union had to pay to keep its allies quiet, writing off Polish debt in 1956 and again in 1981, as well as making economic concessions to Czechoslovakia after 1968. According to estimates, Soviet aid to socialist countries had reached $20 billion a year by the 1980s.92

Development was still uneven. It mainly affected countries, such as Bulgaria or Romania, that had been less well-developed in comparison with the European average before the Communist takeover. But even there, local leaders were more than aware that the price of this development was absolute dependence upon the Soviet Union and that they were, in fact, already bankrupt. When Moscow asked for its money by the end of the 1950s, the Bulgarian leader, Todor Zhivkov, secretly handed over the national gold reserve to the Kremlin. In July 1963, Zhivkov decided to cut the country’s losses by dissolving Bulgaria and integrating it into the USSR as the sixteenth republic. When the Soviet leadership declined, fearing that to do so might incur geopolitical problems, Zhivkov raised the question again in 1973, hoping in this way to pay its debts to Moscow. In order to keep its satellite afloat, the Kremlin decided to subsidise Bulgaria’s economy with up to $600 million annually for agricultural produce and the provision of subsidised oil.93

In real terms, the Central and Eastern European economies could not compete with those of the Western European countries. Productivity was still poor and most of the goods produced were not competitive on world markets, with the result that they could only be traded on the closed socialist markets. Czechoslovakia, for example, which earlier in the century had ranked among the top ten industrialised nations, found it increasingly difficult to compete in Western markets in the 1970s and 1980s with its low-quality manufactured goods. The share of its total trade with less competitive socialist countries rose steadily from 65 % in 1980 to 79 % in 1987. When compared with the structure of employment and the output of goods and services in OECD member countries, it is apparent that agriculture accounted for a larger share of employment and gross domestic product in the Central European economies. Furthermore, the service sector in Central Europe was much smaller than it was in Western Europe. Industry in Central and Eastern European countries was over-concentrated and lacked small and medium-size enterprises. Compared to other European countries, energy consumption in the Communist satellite states of Central and Eastern Europe was two to four times greater than would have been expected based on its per capita GDP. As a result, the technology employed in civilian industries became increasingly backward in relation to the West and the environment suffered increasingly in Central and Eastern Europe. The situation was even worse in the USSR, where waste in all areas was greater and productivity lower. The use of raw materials and energy in the production of each final product was 1.6 and 2.1 times greater, respectively, than it was in the United States. The average construction time for an industrial plant in the USSR was more than ten years, whereas in the United States, it was less than two years. In manufacturing per unit, the USSR used 1.8 times more steel and 7.6 times more fertilizer than the USA. During the 1980s, the level of productivity in the Soviet Union fell by 14 % and dropped to roughly one fifth of the Western level. Productivity in the Baltic countries was higher than it was in other Soviet republics, but in comparison with their capitalist neighbours, the productivity gap widened.94

In view of Communism’s modernist pretensions, it is striking how backward the Eastern bloc remained in the fields of computer technology and telecommunications, the leading sectors in the advancing global revolution. While in West Germany, the number of unskilled workers with a phone rose from 20 % to 58 % in the early 1970s, in East Germany, only one home in seven had a phone in 1990.95 The average waiting time for a new phone in Poland was 13 years. Facsimile had only a small role to play in Central and Eastern Europe because of the poor quality of transmission.96 East German attempts to go in for microchip specialisation resulted only in an annual subsidy of three-billion marks. The computer age, heralded in 1974 by the appearance of the personal computer, did not arrive at all in the Communist world. By the end of the 1980s, the ratio of personal computers per capita was, at best, no more than 10 % of the average Western level.97 At the same time, socialist countries tried to present themselves as vanguards of progress by falsifying data and concealing problems.

In reality, the local Communist leaders were familiar with all of these problems. But to find solutions for them without liquidating some basic Communist principles was impossible. Nevertheless, in the 1970s, a serious attempt was made to win people over to a society whose material well-being compensated for its politics. Socialism was now to take on a more consumerist style. Communist societies were to be ‘normalised’ not only by the security police but also by growing prosperity, washing machines and televisions. It was hoped that people who could set off in their family cars for weekends at their summer homes in the countryside would worry less about the absence of political liberties. Other aspects of life, such as sporting pride or national sentiment, were also exploited. This was all well and good, but in order to achieve these goals, the economies of Central and Eastern Europe were modernised through foreign loans and technology to be paid for by growing exports rather than economic reform. In the beginning, this strategy appeared to be successful. In Poland, wages went up by 40 % in real terms during the early 1970s. Overall, by the end of the 1970s, wages in Central and Eastern Europe were three to four times their 1950 level in real terms. Such growth, however, was not sustainable. In Poland, for example, it resulted in a hard currency debt that stood at $20 billion by 1980, by which time debt service charges had risen to 82 % of exports. Poland had not exploited its Western-derived technology as effectively as had been anticipated and could not even afford the necessary spare parts. The global rise in oil prices and interest rates made the situation even more difficult – it became clear that Poland simply could not pay back its debt.98 The situation was no better in other Communist countries. The $20 billion debt that Hungary owed was approximately double the value of the country’s hard currency export income. Bulgaria too became insolvent and requested a rescheduling of their debt payments, while the leaders of the GDR had to have secret negotiations with West Germany in order to acquire new loans with which to repay the old ones. Romania tried to escape the indebtedness trap by ordering repayment and drastically cutting domestic consumption. The stores were empty, while cities and homes languished in darkness and went unheated in the winter. Everywhere, the socialist command economy descended into irreversible decline and eventual bankruptcy99 (Table 4).

Table 4

Sources: Economist Intelligence Unit 1985, 16, cited in Brown 1989, 507; World Bank 1997a; 1997b. For Yugoslavia, 1984–89; Vienna Institute 1991, 391.

Neither was Yugoslavia, whose model of self-managing socialism had proved quite successful during the 1960s and 1970s, spared these problems. Yugoslavia was effectively a free market where, from 1965 onwards, enterprises were free to dispose of their profits through wages or reinvestment as they saw fit. Foreign investment entered the country, creating the economic growth that raised living standards in the most developed parts of Yugoslavia – today’s Slovenia – almost to the level of neighbouring Austria. However, ‘soft constraints’ and a lack of clear property rights dogged the Yugoslavian success story to the end. Workers’ control of enterprises inhibited the intra-regional mobility of labour and technology, while the Yugoslavian model proved very vulnerable to externally driven inflation. After the death of Tito, international confidence in Yugoslavia’s stability weakened and the inflow of foreign funds decreased. Despite having grown at a rate of over 5 % annually during the 1970s, by 1987, Yugoslavia was experiencing rising unemployment, a five-fold increase in inflation (to 150 %) and drops of 26 % in real net personal income.100

Economic difficulties in the Central and Eastern European satellite countries also created increasing problems for the Soviet Union. First of all, Moscow had to pay for this ‘consumer socialism’ with generous subsidies (Table 5). It was not only a question of supplying low-cost energy that could more profitably have been sold to the West but also of the Soviet Union’s receipt of inferior Eastern bloc manufacturing. Worse still, the satellite countries were extending one hand towards the Soviet Union for support while reaching out to Western countries with the other with a view to developing their own ‘special relations’ with them. Early in 1984, Gosbank in the USSR warned that the satellite countries’ financial situation was becoming dangerously ruinous as ‘the general level of unpaid debt of the socialist countries reached a record for the time of USD 127 billion, and the ability of some of them to pay was very low.’101 The Soviet leaders were extremely displeased by the way in which their Central and Eastern European ‘comrades’ were becoming increasingly dependent on their Western creditors and, through them, on the Western world. In their reports, the Soviet representatives explained that ‘the GDR consumed much more than it was able to produce. The result of this development was a rapid increase in the state’s foreign debt.’ West Germany was ready to provide the necessary loans but only on political conditions, which made the Soviets especially nervous.102 This led to heated debates between Moscow and Berlin, with the Soviet leaders warning the East Germans of the great danger of indebtedness to the West. The East Germans, however, had no other choice than to continue their cooperation with the West. In 1983, Honecker sent a secret letter to Franz Josef Strauss saying that he could not ask Moscow for further help and wanted the West to help him out of the current situation. Moscow was furious at the closer cooperation between the two Germanies, declaring that the measures passed by East Germany to get loans from the West, ‘from the point of view of internal GDR security, are dubious and constitute unilateral concessions to Bonn.’103 Such pressure, however, had little effect; the countries of Central and Eastern Europe had become dependent on the West and there was little the Soviet Union could do to halt the trend (Table 6).

Table 5

Source: Marer 1996, 56. Fuel and nonfood raw materials. For higher estimates, see Marrese and Vanous 1983.

Table 6

Source: July 13, 1989 (GARF, F. 5446, Inv. 150, S. 73, P. 70, 71).

The reasons for the failure of Communism, however, did not lie in subjective mistakes but in the objective contradictions and problems within the Communist system itself. Let us consider the practical rather than the theoretical problems by looking at the economic difficulties that contributed to the economic slowdown, starting with inadequate incentives. The expectation that control and planning would solve the economic problems did not work in reality. A human being’s free will, which is the basic condition for innovation, cannot be incorporated into an economic plan. Communism is simply not capable of innovation and this was one of the main reasons for its failure. The second reason for failure was semi-autarky, the closeness of the Soviet system. For the Communists, the outside world was an alien, uncontrollable source of disruption and therefore it was better not to have too much contact with it. This attitude isolated the Communist countries from the rest of the world and condemned them to backwardness. The third problem in the command economy was its structural inertia. During the initial phase of development, growth in the Communist bloc was fuelled by extensive methods. For some time, the Soviet economy was able to grow without much difficulty while it was sufficient to produce no matter what and no matter how: labour was plentiful and even a waste of capital looked like growth. The system worked more or less satisfactorily as long as the world economy developed in a predictable way, but when the picture became distorted – as always happens – the command economy was not able to respond to the changes. For example, whereas the West began to reform its economies after the energy crisis, the command economies carried on along the same old path of energy-intensive development, expanding old technologies and importing production lines that were just becoming obsolete in the West because of the shift in cost structures. The fourth reason for failure was excessive military spending that was connected with the USSR’s desire to retain the worldwide empire it had created, even in the face of spiralling costs. As a result, while the US had been reducing its military spending since the mid-1950s, in the USSR, it had significantly increased, moving the USSR nearer to collapse. Theoretically it might have been possible to find a way out of this situation, but this would have required the restoration of trust between the government and its people. Under Communism, this was not possible; it was impossible to change the command economy without initiating political change.104

At the same time, the Communists themselves tried to stay optimistic and ‘sell’ Communist ideas via absolutely controlled media to as many citizens as possible. It was announced that people would be living in Communism within a few decades. In 1961, the head of the East German Communists, Walter Ulbricht, forecast the arrival of paradise in the following way:

Our table will be covered with the best nature can offer: prime meat and milk products, the best of the orchard, strawberries and tomatoes at a time when they are not yet ripening on our fields, grapes in winter and not only when in abundance in autumn […]. To imagine that future abundance in the retail outlets, mighty and ever-growing waves of food and specialities from the four corners of the earth, of clothes and shoes of marvellous new materials, of kitchen appliances and working machines, cars big and small, handicrafts and jewellery, cameras and sports equipment.

Protest in East Germany: the question is not bananas but sausage

Unfortunately, with each decade that passed, the Communist countries moved farther away from this dream that actually reflected conditions in the developed capitalist countries of the 1990s and not at all those of the Communist camp.105 The people reacted to Communist brainwashing with enormous numbers of bitter jokes such as: ‘how will the problem of queues in shops be solved when we reach full Communism? There will be nothing left to queue up for.’106

The best evidence of the failure of the Soviet system in Europe was actually created by the Communists themselves – the Berlin Wall, which made the Iron Curtain concrete in the most literal sense of the word. You can placate people for a long time with attractive promises of a better life in the future, but eventually they will realise what is really going on and start voting with their feet. In the period between the end of the Second World War and 1961, a total of 3.8 million people emigrated from East to West Germany. In late 1960 and early 1961, the number of refugees rose dramatically; a critical point had been reached. Every day, thousands of East Germans slipped into West Berlin and from there were flown on to West Germany itself. If the exodus could not be stopped, East Germany would soon cease to exist. The seriousness of the situation was understood in both Berlin and Moscow. The only solution seemed to be to cut East Germany off from the West once and for all. So, on the morning of 13 August 1961, under the protection of hundreds of tanks and thousands of soldiers, the building of wire obstacles dividing East and West Berlin began. Overnight, and with savage finality, families, lovers, friends and neighbourhoods were divided; subway lines, rail links, apartment buildings and phone lines were severed and sealed off. Sunday, 13 August, became known as ‘Stacheldrahtsonntag’ (Barbed Wire Sunday); for the Communists it marked the successful accomplishment of ‘Operation Rose’. Within a few weeks, improvised wire obstacles started to morph into a formidable, heavily fortified, closely guarded and booby-trapped cement barrier dividing the city and enclosing West Berlin. This was ‘the Wall’. Officially, there was little that the West could do, but several organisations were founded in West Berlin to help people from the other side of the Wall to find their way to freedom. With false documents or via secret tunnels, thousands of people reached West Berlin. The escapees proved that the Wall was not impregnable, thereby offering hope to the millions of citizens still trapped in the GDR.107 Many people were killed and even more arrested. During the second half of 1961 alone, 3,041 people were arrested as a result of failed escape attempts and altogether 18,000 individuals were sentenced for ‘political crimes’ in the GDR during that year. Throughout the duration of the Wall’s existence, at least 765 people met their death on the way to freedom, 202 of them in their attempt to get over the Berlin Wall.108 But this did not stop others. There were many innovative escape attempts; by hot-air balloon, hidden in cars, under water or by simply driving a scheduled passenger train into a barrier at full speed, as driver Harry Deterling did on 5 December 1961. Deterling had carefully recruited his 24 passengers for what he called the ‘last train to freedom’. All cowered on the floor of the wagon as the train powered through the final border defences and a hail of bullets swept over them.109

All this demonstrates again the basic failure of Communist thinking, which simply fails to understand that since a human being is created in the image of God, he has a right to make his own decisions. When people are not free to choose, they cannot be creative or innovative. Being able to make innovative decisions also means that they can make mistakes and learn from them. This is also part of being human. Absolute control robs people of the possibility of making such mistakes and this in itself is the greatest mistake of all. Because, without the right to decide, the right to try and the right to be right or wrong, human beings simply could not exist.

82

Handbook, p.198.

83

Handbook 2005, p 133.

84

Handbook 2005, p 208.

85

Handbook 2005, p. 74.

86

Andrew and Mitrokhin 1999, pp. 388–389.

87

Adomeit 1998, p. 151.

88

Beissinger 2002, pp. 330-334.

89

Shattan 1999, p. 226.

90

Janos 2000, pp. 264-328.

91

Gaidar 2007, pp. 102-103.

92

Gaidar 2007, p. 285.

93

The Reunification of Europe 2009, p. 20.

94

Mickiewicz 2005, pp. 4-24; Gros 2004, pp. 41-55; Okey 2004, pp. 24-30; Sachs 1994, pp. 3-22.

95

Okey 2004, p.36.

96

Noam 1992. pp. 78, 99, 274-279.

97

Berend 2009, pp. 24-25.

98

Sachs 2004, pp. 26-34.

99

Janos, pp. 288-324.

100

Janos, pp. 269-281.

101

Gaidar 2007, p.108.

102

Adomeit 1998, p. 128.

103

Adomeit 1998, p. 183.

104

Mickiewicz 2005, pp. 4-16; Janos 2004, pp. 330-338.

105

Gros and Steinherr 2004, p.54.

106

Lewis 2008, p. 210.

107

Taylor 2007.

108

Handbook, p. 208.

109

Taylor 2007, p. 296.