Читать книгу Lucy Maud and Me - Mary Frances Coady - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter One

ОглавлениеA man’s voice echoed just above Laura’s head. She half-opened her eyes and then closed them again, clinging to the jumbled faces in her dream. She stretched her legs and rubbed the stiff spots in her shoulder and arm. As she did, her book slid off her lap and onto the floor. Beneath her feet, the wheels of the train slowed to a rumble.

The train conductor smiled down at her, his pink cheeks shining. “Just about there,” he said. He stooped, picked up the book and handed it back to her.

Laura blinked and looked out the window. The last time she had looked out, she’d seen mile after mile of trees, broken only by the occasional lakeshore and rough beach. Now she saw street after street of houses, red brick and strung together in lines. The train must be entering Toronto.

What had happened to the people in her dream—her father in his air force uniform, her mother’s tear-stained face? Where were Jennifer and Wendy? They had seemed so close, playing hopscotch on the dirt road and giggling. And Peter?

Loneliness welled up inside her; it was as if everyone familiar to her had suddenly disappeared. She considered asking the conductor if she might stay on the train until it headed north to Rocky Falls again. But the spring flood warnings had begun and the whole town had been put on evacuation notice. Her father was gone for now; he had enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force over a year ago. A call had gone out for surgeons and he had answered. Now that he was working in a military hospital in England, thousands of miles away, he wasn’t even able to come home on leave. Her mother was still working full time in a munitions factory and in the evening often helped package up parcels for Canadian soldiers. She intended to continue unless she was forced out by the flood. Because her mother would be working both day and night, she had insisted Laura visit her grandfather while school was out, rather than risk her staying home alone.

She’d never been away from home before, and although it was exciting to be travelling three hours by train to a big city, she felt afraid. What if she got lost? How would she get along without her mother?

“But I can look after myself here, at home,” she had pleaded. “I don’t have to go anywhere. Or—I know—we can go to Toronto together. Or maybe Grandpa can come here.” She stopped, reluctant to admit what was coming next, but then blurted it out. “I just don’t want to go by myself!”

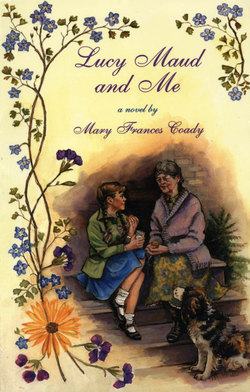

No amount of arguing had changed her mother’s mind. Staring out as the train passed block after block of unfamiliar houses, she wished her mother had relented and come too. She looked down at the book in her lap, The Story Girl. On the cover was the picture of a young girl looking toward a field of daisies. In the distance stood an orchard. The girl’s hair flowed onto her shoulders and she was sitting with her head thrown back, smiling, carefree. Laura picked up the book and leafed through the pages. She had lost her place. She remembered now what the book was about: a group of young people were spending a golden summer together on Prince Edward Island. Sara was the Story Girl, fourteen years of age, who told spell-binding stories about the old folk in the village and their long-dead relatives. The others gathered around her whenever she spoke, caught up in her web of magic.

Prince Edward Island. That was where Grandpa had come from. She stretched and smiled, for the moment forgetting her gloomy mood. She’d soon be seeing him again. For as long as she could remember, he’d come up to Rocky Falls to spend the month of July with her and her parents. “Ah, the fresh air of the country,” he always said, taking in deep breaths as he stood in their back yard. “The city’s no place to spend the summer,” he grumbled. “Especially Toronto. It’s hot as Hades this time of year.”

He spent day after day, sitting and talking on the front verandah. Often in the evenings, Laura sat on the top step while her father worked in the garden and her mother knitted. The knitting needles clicked in rhythm with Grandpa’s voice as he told tales of his childhood on the Island. She loved hearing him tell of how he walked miles over frozen fields to a one-room school and dried his mittens on the black pot-bellied stove under the picture of Queen Victoria, which hung on the wall beside the Union Jack.

“We looked at that picture every morning, the Queen with her white veil and grumpy-looking face, and by jeepers if we didn’t settle down after singing ‘God Save the Queen’. We were afraid she’d reach down from the wall and clip us one if we didn’t behave.” He told her about the slates they’d used instead of notebooks, and about the chestnut tree not far from the school where older girls and boys sometimes carved their initials. He had left as a young man to work in the harvest on the prairies before becoming a doctor in Toronto, but his heart remained in the Prince Edward Island of his boyhood.

Laura smiled to herself. It would be nice to see Grandpa again.

The chugging of the train engine had slowed, and the wheels were moving at a crawl. From the windows across the aisle, Lake Ontario stretched clear to the horizon. Then the train passed into an enclosed area, with steel rafters rising up to a high dome, gave a final shudder, and jerked to a stop. The door at the end of the railway car opened and once again the conductor appeared.

“Union Station, Toronto,” he called out. “End of the line. Everyone out here.”

All around her, passengers rose from their seats and pulled boxes and suitcases from overhead racks. Laura picked up her book and placed it in her knapsack. The conductor stopped beside her, reached up and pulled down a small brown suitcase. “There you are, miss,” he said. “Enjoy your stay in Toronto. Is someone meeting you?”

“My grandfather,” said Laura in a small voice, wondering for a second if indeed Grandpa would be there to meet her.

The conductor helped her down the steps, and then she was swept up with the stream of passengers making their way down a flight of stairs. They climbed up another flight into an enormous lobby where hundreds of people were milling about. Men in uniform—soldiers with khaki sacks thrown over their shoulders, air force men like her father in their blue-grey suits, and even sailors in their white caps and bell-bottom trousers—were everywhere, laughing, walking with their arms around young women who wore long faces and looked close to tears.

“Laura, over here!” she heard from somewhere amid the sea of faces. She looked around. There was Grandpa coming toward her wearing a blue wool sweater and the black cap he always wore to cover his thinning hair. His eyebrows and moustache were as bushy as ever, but a bit whiter than she’d remembered from last summer. She ran with clumsy steps toward him holding her suitcase in one hand and her knapsack in the other. “Grandpa!”

He stooped down to kiss her on the cheek. The roughness of his moustache and the faint smell of liniment he used for sore muscles were comforting. He took her suitcase and looked Laura up and down, as if inspecting her. Familiar crinkles formed around his eyes.

“Well, well,” he said. “My only granddaughter is growing up so quickly I can hardly keep up with her. Let me see now, where do you come up to? Stand up to my shoulder here.” He stood at attention, and she stood next to him. He craned his neck, peering down at her. “You haven’t reached my shoulder yet, but you’re well above my elbow. That’s—what—about four or five inches since last summer?”

Laura grinned and nodded. He picked up her suitcase again and took her by the arm. “Let’s get ourselves out of here. Ever since the war started, this station has been a madhouse with the enlisted men coming through from all over. Because of all the training camps around southern Ontario, they’re talking about reducing train services to civilians even more than they’ve done already.” He smiled down at her. “But thank heavens that hasn’t happened yet, and you’ve been able to visit me.”

Grandpa’s hand was steady and firm on her arm. Looking down at his big feet padding next to hers, she noticed white and brown dog hairs on the cuffs of his trousers.

“Do you still have Sam, Grandpa?”

“I sure do. You’ll see him as soon as we get you back to the house.”

Outside on the street, Laura was amazed at the height of the buildings and the bustle of the street. A man in a maroon uniform stood outside the brass doors of the Royal York Hotel. Car after car passed in front of them in a haze of fumes. Horns honked. A milk wagon drawn by a heavy dray horse drove by, the clip-clop sound blending strangely with honking car horns. A group of soldiers lounged, whistling and laughing loudly, on large piles of baggage, their brown caps set back on their heads.

“We’re lucky to still have taxis,” Grandpa said, leading Laura toward a line of red and yellow cabs. “Now that we have the new gasoline rationing law, who knows how much longer they’ll be able to stay in business?”

It was a relief to be in the safety of a taxi. There were so many people and cars and traffic noise! She thought longingly of the quiet streets of Rocky Falls, where friendly people always said hello and cars stopped if you wanted to cross the road. And just beyond the streets were the country roads that beckoned. She and Peter biked for hours there last summer.

“How is your mother?” Grandpa asked gently as the taxi turned onto Lakeshore Boulevard.

“Fine,” said Laura, not knowing what else to say. She looked outside instead, at the lake.

There was silence for a moment and then he said, his voice quiet, “Any news from your dad?”

For the first time since she had arrived, Laura felt a catch in her throat. “I got a letter from him,” she said, her voice shaky. She pressed her fingers into the palm of her hand. She didn’t want to cry in front of her grandfather. “On thin blue paper. He folded it so that it made its own envelope. He’s in London. That’s where the King and Queen and the princesses live. He didn’t say if he’s seen them yet.”

“What did he say then?”

“He said the food is pretty boring. They just have dried mutton and Brussels sprouts to eat. He said he wished he could have a hot dog sometimes, and some of Mom’s chocolate cake. And he said people use funny words like ‘lorry’ instead of ‘truck’, and ‘cinema’ instead of ‘movie theatre’.” She swallowed and looked down at the knapsack on her lap.

Grandpa pulled at his sweater sleeve and looked over at her with a twinkle in his eye. “And if you called this a ‘sweater’ over in England, people would laugh at you.”

“Why?” asked Laura.

“They’d say, That’s not a sweater. It’s a cardigan. And do you know what they call pullover sweaters? They call them jumpers.”

“Jumpers?! How do you know that, Grandpa”

“Why, didn’t you know? I was over there during the last war. The ‘Great War’ we called it. I suppose if we’re going to call the war that’s going on now the Second World War, we’ll have to call that one the First World War.”

Laura’s mouth hung open. By now she had forgotten her sadness. “Were you in the same place as my dad is?” she asked eagerly.

“No, I was in the army, not the air force. I was stationed in a field hospital in the south of England, where they brought some of the wounded lads across the English Channel.”

“Did you see soldiers fighting?”

“No, I just saw the evidence of the fighting. Men in pretty bad shape. But your dad now, in London—one never knows when the Blitz will start up again—”

Laura felt Grandpa shift beside her. She looked over at him. His mouth was open, as if he was about to say more, then he closed it and sighed. After another moment, he asked, “How’s school?”

“Fine,” she said. “I got a hundred percent in spelling last week. We have a girls’ softball team now. I’m pretty good at pitching.”

“That’s my granddaughter,” he laughed, “a scholar and a sportswoman—oh, and speaking of pitching, look here.” He pointed out the window to a large stadium set against the lake. “That’s the Sunnyside Stadium. The Sunnyside Ladies’ softball team plays there. They play a fine game of softball. Crowds come from all over to watch them.” He smiled down at her. “Maybe you’ll be one of the Sunnyside Ladies some day.”

Before Laura had a chance to answer, he went on, “And look up ahead.” A collection of huge buildings with domes and arches and towers were clustered together, like a group of castles. “See, there are the gates of the C.N.E. just ahead.”

“What does C.N.E. stand for?” asked Laura.

“It’s the Canadian National Exhibition, the biggest exhibition in Canada,” Grandpa explained. “People come here from all over the country.” They both turned their heads as the cab sped past the great arched gates. “It’s too bad you won’t be here in August to see the exhibition and go on the midway rides. On the other hand, it may not be operating this year. I heard on the news that the Ex may be closed down soon so the buildings can be used for armed forces training. But look over here, that’s Sunnyside Park. It’s a terrific beach and amusement park. Things don’t get into full swing until Victoria Day, so it’s about a month early yet.”

Looking out the window, Laura saw roller coasters and ferris wheels and other midway rides standing still along the shore and the colourful fronts of concession stands boarded up. Beyond them stood tall life-guard chairs on an empty beach and, in a gazebo, a family seemed to be setting up an early-spring picnic. Gulls swooped back and forth.

A hard knot had formed inside her stomach. Why had Grandpa sighed and stopped talking about her father? Her mom had said that her dad was in England, nowhere near the war. He wasn’t supposed to be in any danger. Was her mother wrong? The Blitz that Grandpa had begun talking about—where had she heard that word before? Then she remembered, and the knot inside hardened. Soon after the war started, some of the women in Rocky Falls saved up bits of material and got together to make quilts for people in the air-raid shelters. It was because of the Blitz, her mother had said, explaining that Nazi war planes dropped bombs over the English cities at night. Was her father then—?

The taxi made a turn and now the lake was behind them. “We’re getting close to home now,” said Grandpa. “This is Swansea. Used to be a village, but it’s pretty much a part of Toronto now.”

“Are there any kids in your neighbourhood, Grandpa?” asked Laura.

“Kids? Well, not really. Let’s see, who’s in the neighbourhood? Now that I think of it, I’m afraid it’s not a very exciting lot.”

The taxi began to wind up a steep hill, past thick bushes and trees, and for a moment it seemed to Laura that they were out in the country.

“That’s the Humber River, down there below all those bushes,” said Grandpa, pointing.

At the top of the hill, houses appeared on both sides of the road. “Here we have the Hastings,” said Grandpa, pointing to the one on the left. “They’re a family that’s very private. And over there are the Norberts. Their kids are grown and off to school. Right across the street is the Macdonalds’ place. The Reverend Ewan Macdonald, a retired Presbyterian minister. Poor man.”

Laura felt dejected. What was she going to do here with no one but old people and retired ministers?

“Why is he a poor man?” she asked.

“I’ll explain later. What’s more interesting is that his wife is—” But before he could finish, the cab came to a stop in front of a white house shaded by oak and maple trees.