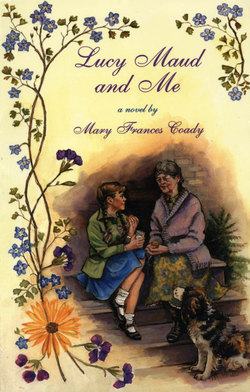

Читать книгу Lucy Maud and Me - Mary Frances Coady - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter Two

ОглавлениеOpening the car door, Laura noticed there were tiny green shoots on the trees, unlike in Rocky Falls where the trees were still bare even though it was past the middle of April.

“Let’s see if Sam is around,” said Grandpa, breaking into her thoughts as he came around the side of the taxi, Laura’s suitcase in his hand. He opened the gate. “Aha! Here’s the official welcome.”

A brown and white spaniel bounded toward them, his big ears flapping. Laura put down her knapsack to stroke him as he jumped up at her.

Inside the front door of the house, she stopped and looked around. The house seemed larger and more grand than their house in Rocky Falls. One wall was lined with bookcases. In the living room, which was furnished with brocade sofas and soft white lamps, she spotted a familiar photograph on the mantelpiece. She and her mother were sitting side by side, smiling into the camera. Laura was dressed in her best blouse and skirt. Long braids hung down over her shoulders, with two big bows. Her mother had had the photograph taken for her father and had sent it to Grandpa as well. Laura hated the picture. She had wanted to wear her hair down, to look more grown-up. But her mother had been firm, saying, “I want your father to see you as you are now.”

“My two favourite ladies in all the world,” said Grandpa as Laura gazed at the photograph. “Now come, I want you to meet Bobbie, my housekeeper.”

At the back of the house, the kitchen was bright with gleaming linoleum on the floor, the walls lined with clean white cupboards. Standing at the stove was a slim, pretty woman, about the same age as Laura’s new teacher, who had come to Rocky Falls straight out of Teachers’ College. She wore bright red lipstick, and her curly brown hair was tied back with a yellow bow. She wore a white housedress splashed with brightly coloured flowers.

“Bobbie, this is the long-awaited Laura,” said Grandpa. He turned to Laura and said, “Bobbie does the cooking and house-cleaning for me. She has supper ready for us and will soon be going home for the day. But first, she’ll show you your room.”

Bobbie wiped her hands on a towel and came toward Laura. “Well, it is lovely to meet you. Here, give me your knapsack.” Her smile was warm, and she smelled of perfume.

Upstairs, Laura gasped with surprise as Bobbie opened the door to her bedroom. The room was filled with white wicker furniture. On the bed was a bedspread patterned with pink roses and festooned with pillows. Best of all was the window across from the bed. White muslin curtains covered the window and in front was a window seat, just like Laura had seen in movies. She ran to the window seat, knelt on the padded cushion, and pulled aside the curtains to look out.

Beyond their trees, on the other side of the street, Laura could see a house with timbered beams. The dark wooden front door gave the house an impenetrable look. It made her think of Grimms’ fairy tales and gingerbread houses. Laura shuddered but remained kneeling on the window seat and gazed at the house. Who did Grandpa say lived there?

“Let’s get you unpacked,” Bobbie said, and Laura turned back to the room. Bobbie set down an armful of towels and smoothed out the bedspread. She lifted Laura’s suitcase and set it on the bed. “May I take your things out?” Laura nodded, and Bobbie began putting her clothes on hangers. Laura noticed a small diamond ring on her left hand.

“What a shame for you, you poor dear, that there’s no one your age here,” said Bobbie. “I was saying to your grandfather the other day that you might be bored in this neighbourhood. He’ll not be much company, having to be at his office all day. His medical practice is much too big for a doctor in his late sixties, if you ask me. Patients are always hounding him for one thing or another. I hope you won’t get lost in the shuffle. Goodness knows, you won’t find much entertainment in me. I just go around all day cooking and cleaning and minding my own business.” She gave Laura a mournful look. “Even the old folk aren’t all that friendly in this part of the city if you ask me—your grandfather excepted, of course,” Bobbie went on. “He’s a gentleman if there ever was one. Do you have things to keep yourself amused?”

Laura opened her knapsack. “I’ve got a book to read,” she said, “and maybe Grandpa can take me to the library.”

“Maybe so,” said Bobbie. “Come to think of it...” She put her hand to her mouth. “No, no, why would I even think of suggesting it? It’s none of my business.” She opened a bureau drawer, a pile of clothes in her hand.

“What?” asked Laura.

“Well, not being much of a reader myself, I really wouldn’t know,” said Bobbie, folding Laura’s things and placing them in the drawer. “But Mrs. Macdonald across the street—the poor old Reverend’s wife—they say she writes books. If you like to read—but no, as I say, it’s not my affair. She’s awfully cranky, anyway.” She closed Laura’s suitcase. “But who wouldn’t be, looking after that man all day and all night?”

Laura pulled The Story Girl from her knapsack and began to leaf through it, trying to find the place where she had left off reading it on the train. She was now only half-listening.

“Well, I really don’t know,” Bobbie continued. “But the poor woman is a real case. I’d avoid her.”

“Who’s a case, Bobbie?” Grandpa asked, at the door.

“Mrs. Macdonald. Oh, I know you have a soft spot for her, Dr. Campbell, but she seems a strange one to me. I can’t figure her out.”

“Maud Macdonald? Well now, I knew her as a girl. She wasn’t always like she is now. She was—but look at that!”

Laura looked up to see her grandfather pointing to the book in her hands.

“I’ll be!” he exclaimed. “That’s one of her books, one of Maud’s books! Look at the name of the author. ‘L.M. Montgomery.’ That’s Maud Macdonald!”

Laura looked at the book, confused. Grandpa went on: “Lucy Maud. Montgomery was her name before she was married. She’s the pride of Cavendish.”

“What do you mean, Grandpa? Where’s Cavendish?”

“Why, that’s where I lived for a short while, back in Prince Edward Island.”

“And?”

“And little Maud was one of the girls in the school there. Funny little thing was Maud. Talked to herself a lot. They said she believed in fairies and such creatures. A fine lass all the same. High-spirited and jolly. And very clever.”

Laura looked down at the book again, at the cover picture of the girl who seemed to be gazing into the distance. She couldn’t believe it!

“I read another book by her,” she said. “It was called Anne of Green Gables. The librarian told me if I liked that book, I’d like this one too. And I do.”

“A great shame,” Grandpa continued. He shook his head. “She’s had it hard these past years. She seems to have turned in on herself now. Of course, one can hardly blame her.” He looked at his watch. “Bobbie, it’s past the time you usually leave. As for Laura and me—it’s suppertime.”

At supper in the panelled dining room, Laura continued to question her grandfather about Mrs. Macdonald. “Are you sure she’s the same person as L.M. Montgomery, Grandpa? Did you know her when she was my age? What was she like?”

Grandpa laughed as he scooped up a forkful of potatoes. “In many ways she was just a normal youngster like the rest of us,” he said. “In the summertime we picked berries and went trout-fishing and walked for miles in the sand along the shoreline. In the winter we sledded down the hills and went to parties in eachother’s homes. Maud was often the life of the party.”

“Grandpa, is she, is she a nice lady? Do you think she’ll she talk to me?”

“Who? Maud?” Her grandfather laughed again. “Well now, ‘nice’ may not be the best word to describe her. She doesn’t bother the neighbors much, I’ll give her that. She keeps to herself. Soon after we moved in here and I discovered that it was Maud living across the street, I went over and introduced myself to the two of them, thinking to get re-acquainted after all these years. The husband was cordial enough, though quiet. Maud seemed to remember me, but didn’t want to reminisce about the old days. She seemed distracted, as if she had too much on her mind. She’s not been well lately. It’s her nerves, mainly. At least, that’s my understanding.”

“What do you mean?” asked Lucy.

“Well, she seems to get easily upset. She’s nervous and anxious about small things that you or I wouldn’t bother ourselves with.”

“What kinds of things?”

Grandpa wiped his plate with a piece of bread. He chewed a moment in silence. “Oh, I don’t know. It’s a big chore just to get herself through the day, I imagine. Of course, it isn’t any wonder, with him the way he is.”

“What’s wrong with him?” she asked.

“You ask a lot of questions that aren’t easy to answer, young lady,” he said, smiling at her. “I’ve never been told, but it may be a condition called senile dementia. Do you know what that means?”

Laura shook her head.

“Sometimes when people get old, they—well, their minds start to go. Just like your body sometimes begins to wear out— your joints get stiff, and your eyes aren’t as good as they used to be, and your hearing begins to go—well, it’s sometimes the same with the mind. You imagine things that aren’t true, you begin to think your friends are against you. Anyway, enough of all that. Here, let me take your plate and I’ll get us some dessert.”

Grandpa piled her plate on top of his and rose from the table. “Having a wife who’s famous doesn’t help either,” he continued. “Times are changing. Women like your mother are working in factories and enlisting in the armed services. But the way we, Ewan and I, were brought up—why, it was considered a man’s duty to support his wife. Ewan’s wife is supporting him.”

He disappeared through the swinging door into the kitchen and re-emerged with two dishes of canned fruit. “A special treat to welcome you,” he said, setting one of the dishes in front of Laura and the other in front of himself. “I don’t know if you’ve noticed, but anything in tins is almost impossible to get anymore. Every bit of tin and steel is being used for the war effort.”

“I know,” said Laura. “And bottles are hard to get too. We collect old bottles and wash them and scrape off the labels and take them to the hardware store. They give us twenty-five cents for a sackful.”

The fruit was chunky and sweet. “Grandpa,” said Laura, licking the syrup from her spoon, “tell me about....”

“Aha! I knew it was coming. Tell me about the olden days.’ Back a hundred years ago, when I was young.”

“Yes, but tell me about Mrs. Macdonald—about Lucy Maud.”

“Ah, Lucy Maud. She hated the name Lucy, I remember. If you called her Lucy Maud, she’d turn her head sharply with her little nose in the air, and her hair would go flying, and she wouldn’t speak to you the rest of the day.” He sat back, wiped his serviette over his moustache, and chuckled.

“I remember sitting behind her in school. One day I took some strands of her hair and knotted them together. Was she in a state! My chum, Nate Lockhart, was awful sweet on her. He would have done anything to have Maud Montgomery as his sweetheart. But no. No one was going to marry Miss Maud. She was going to be a writer—that’s what she always said. She was awfully good at composing, I remember that, even as a young girl. She wrote lovely verses about the sea and adventures of one kind and another, and I remember the excitement the first time she got a poem printed in the Charlottetown paper.”

“What did she look like? Was she pretty?”

“Pretty?” Grandpa cocked his head to one side and appeared to be thinking. “I don’t know if young Maud was exactly pretty. But she had beautiful long brown hair, I remember, reaching past her waist. She had a small nose and a thin mouth. Her chin came to a tiny peak, and her ears were pointed. She looked a bit like a pixie or a wood elf, especially when her eyes got a dreamy look in them.” Grandpa chuckled to himself as he spooned up the last of his fruit.

“Why are you laughing?” asked Laura.

“I’m remembering again how spirited Maud could be when her temper got the better of her.”

Laura leaned forward, smiling eagerly. “What did she do?”

“Well, we had the custom of bringing little bottles of milk to school to drink with our lunch. Of course there were no refrigerators in those days to keep the milk cold, so we placed our bottles in the little brook that ran alongside the school. The running stream kept the milk cool. Then at lunchtime we’d all go whooping down to the brook to collect our bottles of milk and go off and enjoy our lunch. But poor Maud wasn’t allowed to stay at school for lunch. For some reason she had to go home to eat. And was she angry about that! She so badly wanted to have a milk bottle to put in the brook and share the lunch hour with the rest of us.”

As Grandpa spoke, Laura’s mind started to wander. She pictured the little milk bottles with their thick bodies, narrow necks and wide openings nestled in the rocks with a fast flowing stream running over them. But in her daydream the milk wasn’t white in colour, it was brown. Chocolate milk. She remembered— how long ago was it? Two years ago when they were ten?—a school trip to a milk factory. The class had seen the milk being poured from huge vats into regular-sized bottles, like the ones they drank from at home. Then they watched as the bottles moved like toy soldiers in an assembly line toward the arm of a big machine that clamped lids on them. And then, at the end of the tour the children had been given samples of chocolate milk in the kind of small bottles that she imagined lay in the Cavendish brook.

After they drank the chocolate milk, the boys had held a contest with the empty bottles, lining them up on fence posts and throwing pebbles into them. Peter got the highest number of pebbles in his bottle.

What fun they could have had in Toronto together, going to movies and riding the streetcar! The only problem was, Peter was—. She leaned her head on her elbow and stared at the shiny dark wood of the tabletop.

“Shortly after my time in Cavendish, Maud went out west to live with her father,” Grandpa was saying. “She was sixteen, I remember. But her stay out there was short-lived, only a year. She didn’t get along with the father’s new wife, so I heard. But look here, what’s happening to you, my Laura? Are you falling asleep on me?”

Laura felt her eyes closing in spite of herself.

“That’s enough for today,” said Grandpa. “The train trip has tired you out. We’ll do the dishes and then it’s bedtime.”