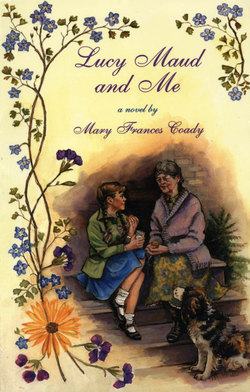

Читать книгу Lucy Maud and Me - Mary Frances Coady - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter Three

ОглавлениеThe next morning, Laura awoke to the sun flooding in her window. She blinked quickly, then closed her eyes again, trying to hold onto her dream.

Grandpa had been in the dream; she was with him on a harvester out west, riding high through the wheat fields. Then, when she turned to look at him, Grandpa had become Peter. She heard him saying in a clear voice, “Long ago, Laura, it was long ago,” and as he spoke the two of them jumped down from the tractor into a vast expanse of water. The swirling foam had risen to her neck; everywhere she looked there was nothing but water. Again she heard Grandpa’s voice: “The water is fine, but oh, the red soil of the Island is finer. Back home is where my heart is.”

Then Grandpa’s voice became Peter’s again, although she could no longer see him in the waves. He went on and on about the seaweed smell of the sea and the yarns that people told when they gathered in the village store or on front verandahs. He talked about the fun on sleigh rides and the fiddle music that filled farmhouses on Saturday nights and how they would push back the furniture and dance the night away. She was struggling to get out of the water.

One eye opened and then the other. As she lay looking at the gleaming white curtains, she wondered why Peter and Grandpa merged in her dream..

It was no use. Her dream had vanished. She reached for her book on the bedside table, began to leaf through it, and then turned to the last page. Reading the last page was something she often did when she was in the middle of a book. This sometimes spoiled the story, but it felt soothing to read the end of this book, because in the final sentences the author talked about how everyone looked forward to the coming of spring.

She heard voices in the hall downstairs.

“I’m glad she’s sleeping late, but I would have liked to at least say good morning to her,” she heard her grandfather say. “I can’t wait any longer. On my way to the hospital I’ll drop by the West Toronto station and send her mother a telegram to let her know Laura arrived safely. Tell Laura I’ll see her this afternoon.”

Then she heard Bobbie’s voice. “Don’t worry, Dr. Campbell. You go off before you’re late. Laura and I will get on just fine.”

Laura stared at the ceiling for a moment. Then, reluctantly, she pushed aside the bedclothes and swung herself out of bed.

Downstairs, Bobbie was dusting the living room furniture with a brown feather duster. A green bandana covered her hair, and she wore a faded apron over her dress. She still wore bright lipstick and her fingernails looked newly polished. She held the duster gingerly. Her diamond ring sparkled. “Well, hello, lazy-bones,” she said in a cheery voice when she saw Laura at the door. “Did you have sweet dreams?”

Laura nodded. “I dreamt about Grandpa,” she said, hesitating, “when he was young.”

“I’ll bet your grandpa was a handsome man when he was young, just like my fiancé.” She wriggled her diamond ring finger in front of Laura. “He enlisted a few months ago. He’s called a private. They’ll be sending him any day now to England. Just like your dad, so your grandpa says. It scares me to think of it.” She lay down the duster and wiped her hands on her apron. “But I shouldn’t worry! I really am proud of him, it’s just that....” She put her arm around Laura’s shoulders. “But come on into the kitchen now. I’ll make you some toast.”

“Why did Grandpa leave so early?” asked Laura when she was seated in the kitchen nook.

“Nine o’clock, my dear girl, is not early. “At nine o’clock some people have been up for hours.”

Laura said nothing as Bobbie served her toast and peanut butter. She wondered what she would do to pass the day.

“He’s usually up and out of here by eight. He stayed later today, but he didn’t want to wake you and he couldn’t wait any longer.” She poured herself a cup of coffee and sat down across from Laura. “I told your grandfather that you’d be welcome to help me clean house....” She smiled broadly. “I hope you know I’m teasing. Anyway, just help me do up these dishes and then you can amuse yourself anyway you like.”

After they had finished doing the dishes and Bobbie returned to her dusting, Laura put on a jacket and went outside. She walked around the house, picking her way through a tangle of garden hose, and then sat on the front doorstep. A crisp morning wind cut through the sunshine, and she pulled her jacket tightly around her. She drew her feet up under her so that the skirt of her dress covered most of her legs. Sam bounded over to her and she stroked his ears. His tail wagged as he settled himself beside her.

Across the street, a woman was drawing a rake through the small green shoots of the lawn. Occasionally she bent over a rock garden surrounding an oak tree, and then resumed, moving the rake in short, jerky movements. Laura watched her for a moment, and then slowly got up and walked toward the gate. Sam trotted beside her. She held onto the gate with both hands, continuing to watch as the woman worked.

The woman held herself rather stiffly as she drew the rake toward her, her hands covered with a pair of gardening gloves. A hairnet covered her dark grey hair and she wore small rimless glasses. This old woman couldn’t have written The Story Girl. She would have no idea what it was like to be young and full of fun. Grandpa must have mistaken her for someone else.

As she watched, the woman seemed to fall forward. She caught herself on the rake, then staggered over to the tree, clutching the trunk. Without thinking, Laura pushed open the gate and ran across the road.

She caught the woman just as she was falling over, and with one arm around her waist and the other holding her arm, Laura guided her to the front steps of her house. Leaning on the iron railing, the woman sat down on the top step. Laura sat beside her. A strand of hair had come loose from under the woman’s hairnet and had fallen over her eyes. As she raised her arm to brush it away, she looked at Laura for the first time.

“You’re a godsend,” she said. Her voice sounded weary. She had a small mouth and her pallor made the blue veins on her forehead stand out. “I don’t know what came over me,” she continued. “I thought I had plenty of strength to start the spring clean-up, especially with today’s lovely sunshine. Haven’t felt much like it until now, and perhaps....” Her thin lips stretched into a slight smile. “Perhaps it’s too much for me. Especially the raking. I’ll leave it for my son and get to the other work.” Grabbing the railing, she heaved herself onto her feet and began to walk slowly along the side of the house, inspecting the plants.

Laura stood up and took a deep breath. Should she offer to help, or should she make her way back to Grandpa’s house and read her book? Sam had flopped down at the far end of the flagstone path.

“Would you like some help?” Laura’s voice sounded like a squeak.

The woman straightened and smiled outright now. “Why yes, that’s very kind of you.” She gestured toward the bushes beyond the sidewalk. “You can pick up the twigs and rubbish over there.” She lumbered toward the steps and from the top landing picked out a paper bag from among a cluster of materials. She handed it to Laura. “It’s amazing the dross that collects here over the winter months and is hidden by the snow. Even dead leaves that I thought we’d gathered up last fall.”

Laura stood holding the paper bag, suddenly feeling awkward, and then took another deep breath. “Are you Mrs. Macdonald?” She could hear the shyness in her own voice.

“Yes,” the woman said. She was bending over the bushes again, snipping here and there with a pruner in her gloved hand. She said nothing else. There was a sharpness in her voice. Then, as if regaining her politeness, she said, “And what is your name?”

Laura half-turned toward her. “Laura.”

Mrs. Macdonald dropped her pruner, took off her gloves, and walked toward Laura, extending her right hand. Her face looked surprised and pleased. Her hand was slender, the nails short and well-tended. Laura took it timidly, not used to grown-ups shaking hands with her.

“I didn’t think they called young girls ‘Laura’ nowadays,” said Mrs. Macdonald, holding Laura’s hand in a firm grasp. “It’s a name that belongs to the last century. When was the last time I heard someone called Laura? Several moons ago, let me tell you. I had a dear friend once whose name was Laura. Laura Pritchard. She was a few years older than you when I knew her. Laura was such a sweet girl. Very pretty too. We had such jolly times.” Her face was animated now. “She had a brother named Will. Poor, dear Will....” Her voice trailed off. She looked at Laura closely, squinting a bit. “As a matter of fact, you look a bit like my Laura. You don’t have a brother Will do you?” She laughed outright now.

Laura shook her head. “I don’t have any brothers or sisters.”

“Thank heaven for that. Much as I loved her, it would never do for you to be another Laura Pritchard.” Her face sobered again and she turned to walk back to where she had been working.

Laura knelt in the soft dirt at the head of a line of bushes. A moment later she heard Mrs. Macdonald’s voice again. “I was an only child too. “

There was silence as they continued working, and then Mrs. Macdonald spoke again. “I’m taking advantage of the first days of mild weather this spring. It’s almost enough to make you feel alive again. Though goodness knows it will take more than a sunny day...” Her voice faded, and Laura swung around toward her, wondering if she might fall over again. But Mrs. Macdonald continued to snip the dead flower heads, the pruner working in slow, rhythmic movements. She seemed lost in her own thoughts. “I’ve always been passionate about my garden. But it’s been about four years now—certainly since the beginning of the war—since I’ve felt much enthusiasm for anything.”

Laura continued looking over at Mrs. Macdonald. She seemed to be talking to herself, as if she had forgotten Laura was there.

Laura turned back to the bush again and for a few moments there was silence between them as she struggled to pick up bits of twigs. Her arms brushed against a branch of a rose bush, and she recoiled from the thorns.

“In the book I’m reading, it says spring is infinitely sweeter than you could ever imagine.” said Laura.

“What do you mean? Where did you read that? What was the name of the book?” Mrs. Macdonald’s sharp tone of voice had returned.

“It’s called The Story Girl,” said Laura. She felt uncertain. She still could hardly believe that Mrs. Macdonald was the author of The Story Girl and Anne of Green Gables as Grandpa had said. And if she was the author, Laura wondered if she had somehow insulted her.