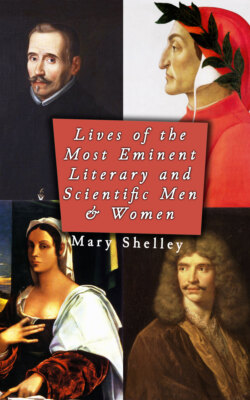

Читать книгу Lives of the Most Eminent Literary and Scientific Men & Women (Vol. 1-5) - Mary Shelley - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1622-1673

ОглавлениеLouis XIV. one day asked Boileau "Which writer of his reign he considered the most distinguished;" Boileau answered, unhesitatingly, "Molière." "You surprise me," said the king; "but of course you know best." Boileau displayed his discernment in this reply. The more we learn of Molière's career, and inquire into the peculiarities of his character, the more we are struck by the greatness of his genius and the admirable nature of the man. Of all French writers he is the least merely French. His dramas belong to all countries and ages; and, as if as a corollary to this observation, we find, also, an earnestness of feeling, and a deep tone of passion in his character, that raises him above our ordinary notions of Gallic frivolity.

Molière was of respectable parentage. For several generations his family had been traders in Paris, and were so well esteemed, that various members had held the places of judge and consul in the city of Paris; situations of sufficient importance, on some occasions, to cause those who filled them to be raised to the rank of nobles. His father, Jean Poquelin, was appointed tapestry or carpet-furnisher to the king: his mother, Marie Cressé31, belonged to a family similarly situated; her father, also, was a manufacturer of carpets and tapestry. Jean Baptiste Poquelin (such was Molière's real name) was horn on the 15th January, 1622, in a house in Rue Saint Honoré, near the Rue de la Tonnellerie. He was the eldest of a numerous family of children, and destined to succeed his father in trade. The latter being afterwards appointed valet de chambre to the king, and the survivorship of the place being obtained for his son, his prospects in life were sufficiently prosperous. His mother died when he was only ten years of age, and thus a family of orphans were left on his father's hands.

Brought up to trade, Poquelin's education during childhood was restricted to reading and writing; and his boyish days were passed in the warehouse of his father. His heart, however, was set on other things. His paternal grandfather was very fond of play-going, and often took his grandson to the theatre of the Hôtel de Bourgogne, where Corneille's plays were being acted. From this old man the youth probably inherited his taste for the drama, and he owed it to him that his genius took so early the right bent. To him he was indebted for another great obligation. The boy's father reproached the grandfather for taking him so often to the play. "Do you wish to make an actor of him?" he exclaimed. "Yes, if it pleased God that he became as good a one as Bellerose32," the other replied. The prejudices of the age were violent against actors. We almost all take our peculiar prejudices from our parents, whom, in our nonage (unless, through unfortunate circumstances, they lose our respect), we naturally regard as the sources of truth. To this speech, to the admiration which the elder Poquelin felt for actors and acting, no doubt the boy owed his early and lasting emancipation from those puerile or worse prejudices against the theatre, which proved quicksands to swallow up the genius of Racine.

1637.

Ætat.

14.

The youth grew discontented as he grew older. The drama enlightened him as to the necessity of acquiring knowledge, and to the beauty of intellectual refinement: he became melancholy, and, questioned by his father, admitted his distaste for trade, and his earnest desire to receive a liberal education. Poquelin thought that his son's ruin must inevitably ensue: the grandfather was again the boy's ally; he gained his point, and was sent as an out-student to the college of Clermont, afterwards of Louis-le-Grand, which was under the direction of the jesuits, and one of the best in Paris. Amand de Bourbon, prince of Conti, brother of the grand Condé, was going through the classes at the same time. After passing through the ordinary routine at this school, the young Poquelin enjoyed a greater advantage than that of being a schoolfellow of a prince of the blood. L'Huilier, a man of large fortune, had a natural son, named Chapelle, whom he brought up with great care. Earnest for his welfare and good education, he engaged the celebrated Gassendi to be Iris private tutor, and placed another boy of promise, named Bernier, whose parents were poor, to study with him. There is something more helpful, more truly friendly and liberal, often in French men of letters than in ours; and it is one of the best traits in our neighbours' character. Gassendi perceived Poquelin's superior talents, and associated him in the lessons he gave to Chapelle and Bernier. He taught them the philosophy of Epicurus; he enlightened their minds by lessons of morals; and Molière derived from him those just and honourable principles from which he never deviated in after life.

Another pupil almost, as it were, forced himself into this little circle of students. Cyrano de Bergerac was a youth of great talents, but of a wild and turbulent disposition, and had been dismissed from the college of Beauvais for putting the master into a farce. He was a Gascon—lively, insinuating, and ambitious. Gassendi could not resist his efforts to get admitted as his pupil; and his quickness and excellent memory rendered him an apt scholar. Chapelle himself, the friend afterwards of Boileau and of all the literati of Paris, a writer of songs, full of grace, sprightliness, and ease, displayed talent, but at the same time gave tokens of that heedless, gay, and unstable character that followed him through life, and occasioned his father, instead of making him his heir as he intended, to leave him merely a slight annuity, over which he had no control. Bernier became afterwards a great eastern traveller.

1641.

Ætat.

19.

Immediately on leaving college Poquelin entered on his service of royal valet de chambre. Louis XIII. made a journey to Narbonne; and he attended instead of his father.[33 This journey is only remarkable from the public events that were then taking place. Louis XIII. and cardinal de Richelieu had marched into Rousillon to complete the conquest of that province from the house of Austria—both monarch and minister were dying. The latter discovered the conspiracy of Cinq-Mars, the unfortunate favourite of the king, and had seized on him and his innocent friend De Thou—they were condemned to death; and conveyed from Tarrascon to Lyons in a boat, which was towed by the cardinal's barge in advance. Terror at the name of the cardinal, contempt for the king, and anxiety to watch the wasting illnesses of both, occupied the court: the passions of men were excited to their height; and the young and ardent youth, fresh from the schools of philosophy, witnessed a living drama, more highly wrought than any that a mimic stage could represent.

1643.

Ætat.

21.

The cardinal had a magnificent spirit; he revived the arts, or rather nursed their birth in France. It has been mentioned in the life of Corneille, that he patronised the theatre; and even wrote pieces for it. The tragedy of the "Cid," while it electrified France, by what might be deemed a revelation of genius, gave dignity as well as a new impulse to the drama. Acting became a fashion, a rage; private theatricals were the general amusement, and knots of young men formed themselves into companies of actors. Poquelin, having renounced his father's trade, and having received a liberal education, entered, it is believed, on the study of the law; having been sent to Orleans for that purpose. He returned to Paris, to commence his career of advocate; here he was led to associate with a few friends of the same rank, in getting up plays: by degrees he became wedded to the theatre; and when the private company resolved to become a public one, and to derive profit from their representations, he continued belong to it; and, according to the fashion of actors in those days assumed a new name—that of Molière. His father was displeased, and took every means to dissuade him from his new course; but the enthusiasm of Molière overcame all opposition. There is a story told, that one respectable friend, who was sent by his father to argue against the theatre, was seduced by the youth's arguments to adopt a taste for it, and led to turn comedian himself. His relations did not the less continue their opposition; they exiled him as it were from among them; and erased the most illustrious name in France for their genealogical tree. What would their tree be worth now did it not bear the name of Molière as its chief bloom, which more rare than the flower of the aloe, which blossoms once in a hundred years, has never had its match.

1645.

Ætat.

23.

There were many admirable actors in Molière's time, chiefly however in comedy. There were the three, known in farce under the names of Gauthier Garguille, Turlupin, and Gros Guillaume, who in the end died tragically, through the effects of fear. Arlechino (Harlequin) and Scaramouche, both Italians, were however the favourites: the latter is said to have been Molière's master in the art of acting; and he never missed a representation at the Italian theatre when he could help it. The native comedy of the Italians gave him a taste for the true humour of comic situation and dialogue; and we owe to his well-founded predilection what we and the German cities (in contradistinction to the French, who judge always by rule and measure, and not by the amusement they receive, nor the genius displayed) prefer to his five act pieces. Nor was this the only source whence he derived instruction. The bustle and intrigue of the Spanish comedies had been introduced by Corneille in his translation of Lope de Vega's "Verdad Sospechosa." Corneille, however, made the character of the Liar, who is the hero, more prominent. Molière is said to have declared, that he owed his initiation into the true spirit of comedy from this play. He took the better part; rejecting the intrigue, disguises, and trap-doors, and discerning the great effect to be produced by a character happily and truly conceived, and then thrown into apposite situations.

There is much obscurity thrown over the earlier portion of Molière's life. We know the names of some of his company. There was Gros René, and his beautiful wife; there were the two Bejarts, brothers, whose excellent characters attached Molière to them, and Madeleine Bejart, their sister, a beautiful girl, the mistress of a gentleman of Modena—to whom Molière was also attached. Molière himself succeeded in the more farcical comic characters.

1646.

Ætat.

24.

The disorders of the capital during the regency at the beginning of Louis XIV.'s reign, and the war of the Fronde, replunged France in barbarism; and torn by faction, the citizens of Paris had no leisure for the theatre. Molière and his troop quitted the city for the provinces, and among other places visited Bordeaux, where he was powerfully protected by the duc d'Epernon, governor of Guienne. It is said, that Molière wrote and brought out a tragedy, called "The Thebaid," in this town, which succeeded so ill, that he gave up the idea of composing tragic dramas, though his chief ambition was to succeed in that higher walk of his art. When we consider the impassioned and reflective disposition of Molière, we are not surprised at his desire to succeed in impersonating the nobler passions; we wonder rather how it was that he should have wholly failed in delineating such, while his greatest power resided in the talent for seizing and portraying the ridiculous.

After a tour in the provinces he returned to Paris. His former schoolfellow, the prince of Conti, renewed his acquaintance with him; and caused him and his company to bring out plays in his palace: and when this prince went to preside at the states of Languedoc, he invited them to visit him there.

1653.

Ætat.

31.

Finding Paris still too distracted by civil broils to encourage the theatre, Molière and his company left it for Lyons. Here he brought out his first piece, "L'Etourdi," which met with great and deserved success. We have an English translation, under the name of "Sir Martin Marplot," originally written by the celebrated duke of Newcastle, and adapted for the stage by Dryden; the French play, however, is greatly superior. In that the lover, Lelie, is only a giddy coxcomb, full of conceit and gaiety of heart. Sir Martin is a heavy plodding fool; and the mistakes we sympathise with, even while we laugh, when originating in mere youthful levity, excite our contempt when occasioned by dull obesity. Thus in the English play, the master appears too stupid to deserve his lady at last—and she is transferred to the servant; a catastrophe which must shock our manners; and we are far more ready to rejoice in the original, when the valet at last presents Celie, with her father's consent, to his master, asking him whether he could find a way even then to destroy his hopes.

The "Dépit Amoureux" followed, which is highly amusing. Although Molière improved afterwards, these first essays are nevertheless worthy his genius.

The company to which he belonged possessed great merit, both in public and private. We cannot expect to find strictness of moral conduct in French comedians, in an age when the manners of the whole country was corrupt, and civil war loosened still more the bonds of society, and produced a state characterised as being "a singular mixture of libertinism and sedition, rife with wars at once sanguinary and frivolous; when the magistrates girded on the sword, and bishops assumed a uniform; when the heroines of the court followed at once the camp and church processions, and factious wits made impromptus on rebellion, and composed madrigals on the field of battle." The war of the Fronde produced a state of license and intrigue: and of course it must be expected that such should be found in a company of strolling actors; to detail the loves of Molière at this time would excite little interest, except inasmuch as it would seem that he brought an affectionate heart and generous spirit, to ennoble what in a less elevated character would have been mere intrigue. Madeleine Bejart was a woman of talent as well as beauty; her brothers were men of good principles and conduct. The sort of liberal, friendly, and frank-hearted spirit that characterised the circle of friends, is well described in the autobiography of a singular specimen of the manners of those times. D'Assouçy was a sort of troubadour; a good musician, and an agreeable poet, who travelled from town to town, lute in hand, and followed by two pages, who took parts in his songs; gaining his bread, and squandering what he gained without forethought. At Lyons, he fell in with Molière, and the brothers Bejart. He continues: "The stage has charms, and I could not easily quit these delightful friends. I remained three months at Lyons, amidst plays and feasts, though I had better not have staid three days, for I met with various disasters in the midst of my amusements (he was stripped of all his money in a gambling-house.) Having heard that I should find a soprano voice at Avignon, whom I could engage to join me, I embarked on the Rhone with Molière, and arrived at Avignon with forty pistoles in my pocket, the relics of my wreck." He then goes on to state how he was stripped of this sum among gamblers and jews; and adds, "But a man is never poor while he has friends; and having Molière and all the family of Bejart as allies, I found myself, despite fortune and jews, richer and happier than ever; for these generous people were not satisfied by assisting me as friends, they treated me as a relation. When they were invited to the States, I accompanied them to Pezenas, and I cannot tell the kindness I received from all. They say that the fondest brother tires of a brother in a month; but these, more generous than all the brothers in the world, invited me to their table during the whole winter; and, though I was really their guest, I felt myself at home. I never saw so much kindness, frankness, or goodness, as among these people, worthy of being the princes whom they personated on the stage."

At Pezenas, to which place they were invited by the prince of Conti, Molière's company found a warm welcome and generous pay from the prince himself. Molière got up, for the prince's amusement, not only the two regular plays which he had written, but other farcical interludes, which became afterwards the groundwork of his best comedies. Among these were the "Le Docteur Pedant;34" "Gorgibus dans le Sac" (the forerunner of "La Fourberies de Scapin"); "Le grand Benet de Fils," who afterwards flourished as "Le Médecin malgré Lui;" "Le grand Benet de fils," who appears to have blossomed hereafter into Thomas Diafoirus, in the "Malade Imaginaire." There were also "Le Docteur Amoureux," "Le Maître d'École," and "La Jalousie de Barbouillé." All these farces perished. Boileau, notwithstanding his love for classical correctness, lamented their loss; as he said, there was always something spirited and animating in the slightest of Molière's works.

These theatrical amusements delighted the prince of Conti; and their author became such a favourite, that he offered him the place of his secretary, which Molière declined. We are told that the prince, with all his kindness of intention, was of such a tyrannical temper, that his late secretary had died in consequence of ill treatment, having been knocked down by the prince with the fire-tongs, and killed by the blow. We do not wonder, therefore, at Molière's refusing the glittering bait. And in addition to the independence of his spirit, he loved his art, and no doubt felt the workings of that genius which hereafter gave such splendid tokens of its existence, and which is ever obnoxious to the trammels of servitude.

He continued for some time in Languedoc and Provence, and formed a friendship at Avignon with Mignard, which lasted to the end of their lives, and to which we owe the spirited portrait of Molière, which represents to the life the eager, impassioned, earnest and honest physiognomy of this great man. As Paris became tranquil Molière turned his eyes thitherward, desirous of establishing his company in the metropolis. He went first to Grenoble and then to Rouen, where, after some negotiation and delay, and several journeys to Paris, he obtained the protection of monsieur, the king's brother; was presented by him to the king and queen-mother, and finally obtained permission to establish himself in the capital.

The rival theatre was at the Hôtel de Bourgogne; here Corneille's tragedies were represented by the best tragic actors of the time.[34] The first appearance of Molière's company before Louis XIV. and his mother, Anne of Austria, took place at the Louvre. "Nicomede" was the play selected; success attended the attempt, and the actresses in particular met with great applause. Yet even then Molière felt that his company could not compete with its rival in tragedy: when the curtain fell, therefore, he stepped forward, and, after thanking the audience for their kind reception, asked the king's leave to represent a little divertisement which had acquired a reputation in the provinces: the king assented; and the performers went on, to act "Le Docteur Amoureux" one those farces, several of which he had brought out in Languedoc, conceived in the Italian taste, full of buffoonery and bustle. The king was amused, and the piece succeeded; and hence arose the fashion of adding a short farce after a long serious play. The success also secured the establishment of his company; they acted at first at the Theatre du Petit Bourbon, and afterwards, when that theatre was taken down to give place to the new building of the colonnade of the Louvre, the king gave him that of the Palais Royal, and his company assumed the name of Comédiens de Monsieur.

Parisian society opened a new field for Molière's talents; subjects for ridicule multiplied around him. The follies which appeared most ludicrous were so nursed and fostered by the high-born and wealthy, that he almost feared to attack them. But they were too tempting. In addition to the amusement to be derived from exhibiting in its true colours an affectation the most laughable, he was urged by the hope of vanquishing by the arms of wit, a system of folly, which had taken deep root even with some of the cleverest men in France;—we allude to the coterie of the Hôtel de Rambouillet; and to the farce of the "Précieuses Ridicules," which entered the very sanctum, and caused irremediable disorder and flight to all the darling follies of the clique.

The society of the Hôtel de Rambouillet had a language and conduct all its own; these were embodied in the endless novels of mademoiselle Scuderi. Gallantry and love were the watchwords, and metaphysical disquisitions were the labours of the set. But these were not allowed to subsist in homely phrase or a natural manner. The euphuism of our Elizabethian coxcombs was tame and tropeless in comparison with the high flights of the heroes and heroines of the Hôtel de Rambouillet. All was done by rule; all adapted to a system. The lover had a regular map laid out, and he entered on his amorous journey, knowing exactly the stoppages he must make, and the course he must pass through on his way to the city of Tenderness, towards which he was bound. There was the village of Billets galans; the hamlet of Billets doux; the castle of Petits Soins; and the villa of Jolis Vers. After possessing himself of these, he still had to fear being forced to embark on the sea of Dislike, or the lake of Indifference; but if, on the contrary, he pushed off on the river of Inclination, he floated happily down to his bourne. Their language was a jargon, which, as Sir Walter Scott observes, in his "Essay on Molière," resembled a highlander's horse, hard to catch, and not worth catching. They gave enigmatic names to the commonest things, which to call by their proper appellations, was, as Molière terms it, du dernier bourgeois. When an "innocent accomplice of a falsehood" was mentioned, a Précieuse (they themselves adopted and gloried in this name; Molière only added ridicules, to turn the blow a little aside from the centre of the target at which he aimed) could, without a blush, understand that a night-cap was the subject of conversation; water with them was too vulgar unless dignified as celestial humidity; a thief could be mentioned when designated as an inconvenient hero; and a lover won his mistress's applause when he complained of her disdainful smile, as "a sauce of pride."

Purity of feeling however was the soul of the system. Authors and poets were admitted as admirers, but they never got beyond the villa of Jolis Vers. When Voiture, who had glorified Julie d'Angennes his life-long, ventured to kiss her hand, he was thrown from the fortifications of the castle of Petit Soins, and soused into the lake of Indifference: even her noble admirer, the duke Montauzier, was forced to paddle on the river of Inclination, for fourteen years35, before he was admitted to the city of Tenderness, and allowed to make her his wife. Their style of life was as eccentric as their talk. The lady rose in the morning, dressed herself with elegance, and then went to bed. The French bed, placed in an alcove, had a passage round it, called the ruelle; to be at the top of the ruelle was the post of honour; and Voiture, under the title of Alcovist, long held this envied post, beside the pillow of his adored Julie, while he never was allowed to touch her little finger. The folly had its accompanying good. The respect which the women exacted, and the virtue they preserved, exalted them, and in spite of their high-flown sentiments, and metaphysical conceits, wits did not disdain to "put a soul into the body of" nonsense. Rochefoucauld, Menage, madame de Sévigné, madame Des Houillères, Balzac, Vaugelas, and others, frequented the Hôtel de Rambouillet, and lent the aid of their talents to dignify their galimathias.

But it was too much for the honest comic poet to bear. He perceived the whole of society infected—nobles and prelates, ladies and poets, marquisses and lacqueys, all wandered about the Pays de Tendre, lost in a very labyrinth of inextricable nonsense. They assumed fictitious names36, they promulgated fictitious sentiments; they admired each other, according as they best succeeded in being as unnatural as possible. Molière stripped the scene and personages of their gilding in a moment. His fair Précieuses were the daughters of a bourgeois named Gorgibus, who quitted their homely names of Cathos and Madelon, for Aminte and Polixene, dismissed their admirers for proposing to marry them, scolded their father for not possessing le bel air des choses, and are taken in by two valets whom they believe to be nobles, who easily imitate the foppery and sentimentalism, which these young ladies so much admire.37

1659.

Ætat.

37.

The success of the piece was complete—from that moment the Hôtel de Rambouillet talked sense. Menage says: "I was at the first representation of the "Précieuses Ridicules" of Molière, at the Petit Bourbon, mademoiselle de Rambouillet, madame de Grignan, M. Chapelain, and others, the select society of the Hôtel de Rambouillet, were there. The piece was acted with general applause; and for my own part I was so delighted that I saw at once the effect that it would produce. Leaving the theatre, I took M. Chapelain by the hand, and said We have been used to approve all the follies so well and wittily satirised in this piece; but believe me, as St. Remy said to king Clovis—'We must burn what we have adored, and adore what we have burnt.' It happened as I predicted, and we gave up this bombastic nonsense from the time of the first representation." A better victory could not have been gained by comic poet: to it may be said to have been added another. While the Précieuses yielded to the blow, unsophisticated minds enjoyed the wit: in the midst of the piece, an old man cried out suddenly from the pit, "Courage, Molière, this is true comedy!" The author himself felt that he had been inspired by the spirit of comic drama. That this consisted in a true picture of the follies of society, idealised and grouped by the fancy, but in every part in accordance with nature. He became aware, that he had but to examine the impression made on himself, and to embody the conceptions they suggested to his mind. As he went on writing, he in each new piece made great and manifest improvement. "Sganarelle" was his next effort: it is, perhaps, not in his best taste; it is like a tale of the Italian novelists—that the husband's misfortune had existence in his fancy only is the author's best excuse.

1661.

Ætat.

39.

Success ought to have taught Molière to abide by comedy, and to become aware that a quick sense of the ridiculous, and a happy art in the scenic representation of it, was the bent of his genius. But a desire to succeed in a more elevated and tragic style still pursued him. He brought out "Don Garcie de Navarre," a very poor play, unsuccessful in its début, and afterwards so despised by the author as not to be comprised in his edition of his works. He quickly dissipated this cloud, however, by bringing out "L'École des Maris," one of his best comedies.

The splendours of the reign of Louis XIV. were now beginning to shine out in all their brilliancy. The first attempt, however, at a fête—superior in magnificence, originality, and beauty to any thing the world had yet seen—was made, not by the king himself. In an evil hour for himself, Fouquet, the minister of finances, got leave to entertain royalty at his villa, or rather palace of Vaux. Blinded by prosperity, this unfortunate man thought to delight the king by the splendor of his entertainment; he awoke indeed a desire to do the like in Louis's mind, but he gave the final blow to his own fortunes, already undermined. Fouquet had admired mademoiselle de la Vallière; he had expressed his admiration, and sought return with the insolence of command rather than the solicitations of tenderness: he was rejected with disdain. His mortification made him suspect another more successful lover: he discovered the hidden and mutual passion of the king and the beautiful girl; and, with the most unworthy meanness, he threatened her with divulging the secret; and added the insolence of an epigram on her personal appearance. La Vallière informed her royal lover of the discovery which Fouquet had made—and his fall was resolved on.

The minister had lavished wealth, taste, and talent on his fête. Le Brun painted the scenes; Le Nôtre arranged the architectural decorations; La Fontaine wrote verses for the occasion; Molière not only repeated his "École des Maris," but brought out a new species of entertainment: a ballet was prepared, of the most magnificent description; but, as the principal dancers had to vary their characters and dresses in the different scenes, that the stage might not be left empty and the audience get weary with waiting, he composed a light sketch, called "Les Fâcheux" (our unclassical word bore is the only translation), in which a lover, who has an assignation with his mistress, is perpetually interrupted by a series of intruders, who each call his attention to some subject that fills their minds, and is at once indifferent and annoying to him. A novel sort of amusement added therefore charms to luxury and feasting; but the very perfection of the scene awoke angry feelings in Louis's mind: he saw a portrait of La Vallière in the minister's cabinet, and was roused to jealous rage: disdaining to express this feeling, he pretended another cause of displeasure, saying that Fouquet must have been guilty of peculation, to afford so vast an expenditure. He would have caused him to be arrested on the instant, had not his mother stopped him, by exclaiming, "What, in the midst of an entertainment which he gives you!"

Louis accordingly delayed his revenge. A glittering veil was drawn over the reality. With courtly ease he concealed his resentment by smiles; and, while meditating the ruin of the master and giver of the feast, entered with an apparently unembarrassed mind on the enjoyment of the scene. He was particularly pleased with "Les Fâcheux;" but, while he was expressing his approbation to Molière, he saw in the crowd Grand Veneur, or great huntsman to the king, a Nimrod devoted to the chase; and he said, pointing to him, "You have omitted one bore." On this Molière went to work; he called on M. de Soyecourt, slily engaged him in one of his too ready narrations of a chase; and, on the following evening, the lover had added to his other bores a courtier, who insists on relating the history of a long hunting-match in which he was engaged. English followers of the field find ample scope for ridicule in this scene, which in their eyes contrasts the rules of French sport most ludicrously with their more manly mode of running down the game. Another more praiseworthy effort to please and flatter the king in this piece was the introducing an allusion to Louis's efforts to abolish the practice of duelling.

The success of Molière and his talent naturally led to his favor among the great. The great Condé delighted in his society; and with the delicacy of a noble mind told him, that, as he feared to trespass on his time inopportunely if he sent for him; he begged Molière when at leisure to bestow an hour on him to send him word, and he would gladly receive him. Molière obeyed; and the great Condé at such times dismissed his other visitors to receive the poet, with whom he said he never conversed without learning something new. Unfortunately this example was not followed by all. Many little-minded persons regarded with disdain a man stigmatised with the name of actor, while others presumed insolently on their rank. The king generously took his part on these occasions. The anecdotes indeed which displays Louis's sympathy for Molière are among the most agreeable that we have of that monarch, and are far more deserving of record than the puerilities which Racine has commemorated. When brutally assaulted by a duke, the king reproved the noble severely. Madame Campan tells a story still more to this monarch's honour. Molière continued to exercise his functions of royal valet de chambre, but was the butt of many impertinences on account of his being an actor. Louis heard that the other officers of his chamber refused to eat with him, which caused Molière to abstain from sitting at their table. The king, resolved to put an end to these insults, said one morning, "I am told you have short commons here, Molière, and that the officers of my chamber think you unworthy of sharing their meals. You are probably hungry, I always get up with a good appetite; sit at that table where they have placed my en cas de nuit" (refreshment, prepared for the king in case he should be hungry in the night, and called an en cas.) The king cut up a fowl; made Molière sit down, gave him a wing, and took one himself, just at the moment when the doors were thrown open, and the most distinguished persons court entered, "You see me," said the king, "employed in giving Molière his breakfast, as my people do not find him good enough company for themselves." From this time Molière did not need to put himself forward, he received invitations on all sides. Not less delicate was the attention paid him by the poet Bellocq. It was one of the functions of Molière's place, to make the king's bed; the other valets drew back, averse to sharing the task with an actor; Bellocq stept forward, saying, "Permit me, M. Molière, to assist you in making the king's bed."

It was however at court only that Molière met these rebuffs; elsewhere his genius caused him to be admired and courted, while his excellent character secured him the affection of many friends. He brought forward Racine; and they continued intimate till Racine offended him by not only transferring a tragedy to the theatre of the Hôtel de Bourgogne, but seducing the best actress of his company to that of the rival stage. With Boileau he continued on friendly terms all his life. His old schoolfellow, "the joyous Chapelle," was his constant associate; though he was too turbulent and careless for the sensitive and orderly habits of the comedian.

Molière indeed was destined never to find a home after his own heart. Madeleine Bejart had a sister38 much younger than herself, to whom Molière became passionately attached. She was beautiful, sprightly, clever, an admirable actress, fond of admiration and pleasure. Molière is said to describe her in "Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme," as more piquante than beautiful—fascinating and graceful—witty and elegant; she charmed in her very caprices. Another author speaks of her acting; and remarks on the judgment she displays both in dialogue and by-play: "She never looks about," he says, "nor do her eyes wander to the boxes; she is aware that the theatre is full, but she speaks and acts as if she only saw those with whom she is acting. She is elegant and rich in her attire without affectation: she studies her dress, but forgets it the moment she appears on the stage; and if she ever touches her hair or her ornaments, this bye-play conceals a judicious and inartificial satire, and she thus enters more entirely into ridicule of the women she personates: but with all these advantages, she would not please so much but for her sweet-toned voice. She is aware of this, and changes it according to the character she fills." With these attractions, young and lovely, and an actress, madame (or as she was called according to the fashion of the times, which only accorded the madame to women of rank, mademoiselle) Molière, fancying herself elevated to a high sphere when she married, giddy and coquettish, disappointed the hopes of her husband, whose heart was set on domestic happiness, and the interchange of affectionate sentiments in the privacy of home. Yet the gentleness of his nature made him find a thousand excuses for her:—"I am unhappy," he said, "but I deserve it; I ought to have remembered that my habits are too severe for domestic life: I thought that my wife ought to regulate her manners and practices by my wishes; but I feel that had she done so, she in her situation would be more unhappy than I am. She is gay and witty, and open to the pleasures of admiration. This annoys me in spite of myself. I find fault—I complain. Yet this woman is a hundred times more reasonable than I am, and wishes to enjoy life; she goes her own way, and secure in her innocence, she disdains the precautions I entreat her to observe. I take this neglect for contempt; I wish to be assured of her kindness by the open expression of it, and that a more regular conduct should give me ease of mind. But my wife, always equable and lively, who would be unsuspected by any other than myself, has no pity for my sorrows; and, occupied by the desire of general admiration, she laughs at my anxieties." His friends tried to remonstrate in vain. "There is but one sort of love," he said, "and those who are more easily satisfied do not know what true love is." The consequence of these dissensions was in the sequel a sort of separation; full of disappointment and regret for Molière, but to which his young wife easily reconciled herself. Her conduct disgraced her; but she had not sufficient feeling either to shrink from public censure or the consciousness of rendering her husband unhappy. To these domestic discomforts were added his task of manager; the difficulty of keeping rival actresses in good humour, the labour of pleasing a capricious public.

The latter task, as well as that of amusing his sovereign, was by far the easiest; as in doing so he followed the natural bent of his genius. He had begun the "Tartuffe." He brought out "L'École des Femmes," one of his gayest and wittiest comedies. It is known in England, through the adaptation of Wycherly; and called "The Country Girl." Unfortunately, in his days, the decorum of the English stage was less strict than the French; and what in Molière's play was fair and light raillery, Wycherly mingled with a plot of a licentious and disagreeable nature. The part, however, of the Country Girl herself, personated by Mrs. Jordan, animated by her bewitching naïveté, and graced by her frank, joyous, silver-toned voice, was an especial favourite with the public in the days of our fathers. In Paris, the critics were not so well pleased; truth of nature they called vulgarity, familiarity of expression was a sin against the language. Molière deigned so far to notice his censurers as to write the "Critique de l'École des Femmes," in which he easily throws additional ridicule on those who attacked him. The "Impromptu de Versailles" was written in the same spirit, at the command of the king. The war of words thus carried on, and replied to, grew more and more bitter: personal ridicule was exchanged by his enemies for calumny. Monfleuri, the actor, was malicious enough to present a petition to the king, in which he accused Molière of marrying his own daughter. Molière never deigned to reply to his accusation; and the king showed his contempt by, soon after, standing godfather to Molière's eldest child, of whom the duchess of Orleans was godmother.

1664.

Ætat.

42.

In those days, as in those of our Elizabeth, the king and courtiers took parts in the ballets.39 These comédie-ballets were of singular framework; comedies, in three acts, broad almost to farce, were interspersed with dances: to this custom, to the three act pieces that thus came into vogue, we owe some of the best of Molière's plays; when, emancipated from the necessity of verse and five acts, he could give full play to his sense of the ridiculous, and talent for comic situation; and when, unshackled by rhyme, he threw the whole force of his dry comic humour into the dialogue, and by a single word, a single expression, stamp and immortalise a folly, holding it up for ever to the ridicule it deserved. This seizing as it were on the bared inner kernel of some fashionable vanity, and giving it its true and undisguised name and definition, often shocked ears polite. They called that "vulgar," which was only stripping selfishness or ignorance of its cloak, and bringing home to the hearts of the lowly-born the fact, that the follies of the great are akin to their own: the people laughed to find the courtier of the same flesh and blood; but the courtier drew up, and said, that it was vulgar to present him en dishabille to the commonalty. "Let them rail," said Boileau, to the poet, whose genius he so fully appreciated, "let them exclaim against you because your scenes are agreeable to the vulgar. If you pleased less how much better pleased would your censurers be!" "Le Mariage Forcé" was the first of these comédies ballets. The king danced as an Egyptian in the interludes while in the more intellectual part of the performance Molière delighted the audience as "Sganarelle"—the unfortunate man, who with such rough courtesy is obliged to take a lady for better or for worse; a plot, founded on the last English adventure of the count de Grammont, who, when leaving this country, was followed by the brothers of la belle Hamilton, who, with their hands on the pummels of their swords, asked him if he had not forgotten something left behind. "True," said the count, "I forgot to marry your sister and instantly went back to repair his lapse of memory, by making her countess de Grammont." The dialogue of this play is exceedingly amusing; the metaphysical or learned pedants, whom Sganarelle consults, are admirable and witty specimens of advisers, who will only give counsel in their own way, in language understood only by themselves. The "Amants Magnifiques" followed; it was written in the course of a few days: it is now considered the most feeble of Molière's plays; but it suited the occasion, and by a number of delicate and witty impersonations of the manners of the times, lost to us now, it became the greatest ornament of a succession of festivals; which under the name of "Plaisirs de l'Ile enchantée," were got up in honour of mademoiselle de Vallière; and, being prepared by various men of talent, gave the impress of ideal magnificence to the pleasures of Louis XIV. On this occasion Molière ventured to bring out the three first acts of the "Tartuffe," hoping to gain the king's favourable ear at such a moment. But it was ticklish ground; and Louis, while he declared that he appreciated the good intentions of the author, forbade its being acted, under the fear that it might bring real devotion into discredit. The "Tartuffe" was a favourite with Molière, who, degraded by the clergy on account of his profession, and aware that virtue and vice were neither inherent in priest nor actor according to the garb, was naturally very inimical to false devotion. He still hoped to gain leave to represent his satire on hypocrites. He knew the king in his heart approved the scope of his play, and was pleased that his own wit should have been considered worthy of transfer to Molière's scenes—Molière himself venturing to remind him of the incident, which occurred during a journey to Lorraine, when Molière accompanied the monarch as his valet. When travelling, Louis was accustomed to make his supper his best meal, to which, of course, he brought a good appetite: one afternoon he invited his former preceptor, Perefixe, bishop of Rhodes, to join him; but the prelate, with affected sanctity, declined, as he had dined, and never ate a second meal on a fast-day. The king saw a smile on a bystander's face at this answer, and asked the cause. In reply, the courtier said, that it arose from his sense of the bishop's self-denial, considering the dinner he enjoyed. The detail of the dinner followed, dish after dish in long succession; and the king, as each viand was named, exclaimed, le pauvre homme! with such comic variety of voice and look, that Molière, who was present, felt the wit conveyed, and transferred it to his play, in which Orgon, in the simplicity of his heart, repeats this exclamation when the creature-comforts in which Tartuffe indulges are detailed to him. But though this compliment was not lost on the king, he did not yield; and Molière was obliged to content himself—after acting it at Rainey, the country house of the prince of Condé—by reading it in society, and thus giving opportunity for it to awaken the most lively curiosity in Paris. There is a well-known print of his reading it to the celebrated Ninon de l'Enclos, whose talents and wonderful tact for seizing the ridiculous he appreciated highly; and to whom he partly owed the idea of the play, from an occurrence that befel her.40 Yet he was not consoled by these private readings and the sort of applause he thus gained, and he grew more bitter against the devotees for their opposition: in his play on the subject of Don Juan, "Le Festin de Saint Pierre," brought out soon after, he alludes bitterly to the interdiction laid on his favourite work. "All other vices," he says, "are held up to public censure; but hypocrisy is privileged to place the hand on every one's mouth, and to enjoy impunity." The hypocrites revenged themselves by calling his Festin blasphemous. The king, however, remained his firm friend, and tried to compensate for the hardship he suffered on this occasion by giving his name to his company, and granting him a pension in consequence.

It was the custom for the soldiers of the body guard of the king, and other privileged troops, to frequent the theatre without paying. These people filled the pit, to the great detriment of the profits of the actors. Molière, incited by his comrades, applied to the king, who issued an order to abrogate this privilege. The soldiers were furious; they went in crowds to the theatre, resolved to force an entrance; the unfortunate door-keeper was killed by a thousand sword-thrusts, and the rioters rushed into the house, resolved to revenge themselves on the actors, who trembled at the storm they had brought on themselves. The younger Bejart encountered their fury with a joke, that somewhat appeased them: he was dressed for the part of an old man; and came tottering forward, imploring them to spare the life of a poor old man, seventy-five years of age, who had only a few days of life left. Molière made them a speech; and peace was restored, with no greater injury than fear to the actors—except to one, who in his terror tried to get through a hole in the wall to escape, and stuck so fast that he could neither get out nor in, till, peace being restored, the hole was enlarged. The king was ready to punish the soldiers as mutineers, but Molière was too prudent to wish to make enemies; when the companies were assembled, and put under arms, that the ringleaders might be punished, he addressed them in a speech, in which he declared that he did not wish to make them pay, but that the order was levelled against those who assumed their name and claimed their privilege: and that, in truth, a gratuitous entrance to the theatre was a right beneath their notice; and, by touching their pride, he brought them for a time to submit to the new order.

In holding up follies or vices to ridicule Molière made enemies; and by attacking whole bodies of men, dangerous ones; yet, how much did the public owe to the spirit and wit with which he exposed the delusions to which they were often the victims. He first attacked the faculty, as it is called in "L'Amour Médecin," in which he brings forward four of the physicians in ordinary to the king, empirics of the first order, under Greek names, invented by Boileau for the occasion: nor can we wonder, when we read the mémoires and letters of the times, at the contempt in which Molière held the medicinal art. One specific came into fashion after the other; quack succeeded to quack; and the more ignorant the greater was the pretension, the greater also the number of dupes. Reading these, and turning to the pages of Molière, we see in a minute that he by no means exaggerated, while he with his happy art seized exactly on the most ridiculous traits.

1666.

Ætat.

42.

It has been said that the "Misanthrope," now considered by the French as Molière's chef-d'œuvre, was coldly received at first—a tradition contradicted by the register of the theatre; it went through twenty-one consecutive representations, and excited great interest in Paris. Still in this he raises his voice against the false taste of the age; and this with so little exaggeration, that the pit applauded the sonnet introduced in ridicule of the prevailing poetry, and were not a little astonished when Alceste proves that it possesses no merit whatever. The audience, seeing that ridicule of reigning fashions was the scope of the play, fancied that various persons were intended to be represented; and, among others, it was supposed that the duke de Montauzier, the husband of the Précieuse Julie d'Angennes, was portrayed in Alceste. It is said, that the duke went to see the play, and came back quite satisfied; saying, that the "Misanthrope" was a perfectly honest and excellent man, and that a great honour, which he should never forget, was done him by assimilating them together. There is indeed in Alceste a sensibility, joined to his sincerity and goodness of heart, that renders him very attractive; and thus, as is often the case when genius mirrors nature, the ridicule the author pretends to wish to throw on the victim recoils on the apparently triumphant personages: the time-serving Philinthe is quite contemptible; and every honest heart echoes the disgust Alceste feels for the deceits and selfishness of society. In truth, there is some cause to suspect that Molière found in his own sensitive and upright heart the homefelt traits of Alceste's character, as that of his wife furnished him with the coquetry of Célimène; and when, in the end, the Misanthrope resolves to hide from the world, one of the natures of the author poured itself forth; a nature, checked in real life by the necessities of his situation and the living excitement of his genius.

During the same year the "Médecin malgré Lui" was brought out; whose wit and comedy stamps it as one of his best: other minor pieces, by command, occupied his time, without increasing his fame. His mind was set on bringing out the "Tartuffe." The king had yielded to the outcry against it; but in his heart he was very desirous of having it acted. On occasion of a piece being played, called "Scaramouche Hermite," which also delineated immorality cloaked by religion; the king said to the great Coudé, "I should like to know why those who are so scandalised by Molière's play, say nothing against that of Scaramouche?" The prince replied. "The reason is, that Scaramouche makes game of heaven and religion, which these people care nothing for; but Molière satirises them themselves, and this they cannot bear."41 Confident in the king's support, and anxious to bring out his play, Molière entertained the hope of mollifying his opponents by concessions: he altered his piece, expunged the parts most disliked, and changed the name Tartuffe, already become odious to bigot ears, to the Imposteur. In this new shape his comedy was acted once; but, on the following day the first president, Lamoignon, forbade it. Molière dispatched two principal actors to the king, then in Flanders, to obtain permission; but Louis only promised that the play should be re-examined on his return. Thus, once more, the piece was laid aside; and Molière forced to content himself with private readings, and the universal interest excited on the subject. Meanwhile he brought out "Amphitryon," "L'Avare," and "George Dandin" all of which rank among his best plays. The first has a more fanciful and playful spirit added to its comedy than any other of his productions, and displays more elegance and a more subtle wit.

As a specimen of mingled wit and humour, let us take the scene between Sosia and Mercury, when the latter, assuming his name and appearance, attempts to deprive him of his identity by force of blows. Sosia exclaims,—

"N'importe. Je ne puis m'anéantir pour toi,

Et souffrir un discours si loin de l'apparence.

Être ce que je suis est-il en ta puissance?

Et puis-je cesser d'être moi?

S'avisa-t-on jamais d'une chose pareille?

Et peut-on démentir cent indices pressants?

Rêvé-je? Est-ce que je sommeille?

Ai-je l'esprit troublé par des transports puissants?

Ne sens-je bien que je veille?

Ne suis-je pas dans mon bon sens?

Mon maître Amphitryon ne m'a-t-il pas commis

À venir en ces lieux vers Alemène sa femme?

Ne lui dois-je pas faire, en lui vantant sa flamme,

Un récit de ses faits contre notre ennemi?

Ne suis-je pas du port arrivé tout à l'heure?

Ne tiens-je pas une lanterne en main?

Ne te trouvé-je pas devant notre demeure?

Ne t'y parlé-je pas d'un esprit tout humain?

Ne te tiens-tu pas fort de ma poltronnerie,

Pour m'empêcher d'entrer chez nous?

N'as-tu pas sur mon dos exercé ta furie?

Ne m'as tu pas roué de coups?

Ah, tout cela n'est que trop veritable;

Et, plût au ciel, le fût-il moins!

Cesse donc d'insulter au sort d'un misérable;

Et laisse à mon dévoir s'acquitter de ses soins.

MERCURE.

Arrête, ou sur ton dos le moindre pas attire

Un assommant éclat de mon juste courroux.

Tout ce que tu viens de dire,

Est à moi, hormis les coups.

SOSIE.

Ce matin du vaisseau, plein de frayeur en l'âme,

Cette lanterne sait comme je suis parti.

Amphitryon, du camp, vers Alemène sa femme,

M'a-t-il pas envoyé?

MERCURE.

Vous avez menti.

C'est moi qu'Amphitryon députe vers Alemène

Et qui du port Persique arrivé de ce pas;

Moi qui viens annoncer la valeur de son bras,

Qui nous fait remporter une victoire pleine,

Et de nos ennemis a mis le chef à bas.

C'est moi qui suis Sosie enfin, de certitude,

Fils de Dave, honnête berger;

Frère d'Arpage, mort en pays étranger;

Mari de Cléanthis la prude,

Dont l'humeur me fait enrager;

Qui dans Thèbes ai reçu mille coups d'étrivière

Sans en avoir jamais dit rien;

Et jadis en public fus marqué par derrière

Pour être trop homme de bien.

SOSIE (bas, à part).

Il a raison. A moins d'être Sosie,

On ne peut pas savoir tout ce qu'il dit;

Et, dans l'étonnement dont mon âme est saisie,

Je commence, à mon tour, a le croire un petit.

En effet, maintenant que je le considère,

Je vois qu'il à de moi taille, mine, action.

Faisons-lui quelque question,

Afin, d'éclaircir ce mystère.

(Haut.)

Parmi tout le butin fait sur nos ennemis,

Qu'est-ce qu'Amphitryon obtient pour son partage?

MERCURE.

Cinq fort gros diamants en nœud proprement mis,

Dont leur chef se paroit comme d'un rare ouvrage.

SOSIE.

A qui destine-t'-il un si riche présent?

MERCURE.

A sa femme, et sur elle il le veut voir paroitre.

SOSIE.

Mais où, pour l'apporter, est-il mis à présent?

MERCURE.

Dans un coffret scellé des armes de mon maître.

SOSIE (à part).

Il ne ment pas d'un mot à chaque repartie,

Et de moi je commence à douter tout de bon.

Près de moi par la force, il est déjà Sosie,

Il pourroit bien encore l'être par la raison;

Pourtant quand je me tâte et que je me rappelle,

Il me resemble que je suis moi.

Où puis-je rencontrer quelque clarté fidèle.

Pour démêler ce que je voi?

Ce que j'ai fait tout seul, et que n'a vu personne,

A moins d'être moi-même, on ne le peut savoir:

Par cette question il faut que je l'étonne;

C'est de quoi le confondre, et nous allons le voir.

(Haut.)

Lorsqu'on étoit aux mains, que fis-tu dans nos tentes,

Où tu courus seul te fourrer?

MERCURE.

D'un jambon——

SOSIE (bas, à part).

L'y voila!

MERCURE.

Que j'allai déterrer,

Je coupai bravement deux tranches succulentes,

Dont je sus fort bien me bourrer.

Et, joignant à cela d'un vin que l'on ménage,

Et dont, avant le goût, les yeux se contentoient.

Je pris un peu de courage,

Pour nos gens qui se battoient.

SOSIE.

Cette preuve sans pareille

En sa faveur conclut bien,

Et l'on n'y peut dire rien,

S'il n'étoit dans la bouteille."

And again, when Sosia tries to explain to Amphitryon how another himself prevented him from entering his house:—

"Faut-il le répéter vingt fois de même sorte?

Moi vous dis-je, ce moi, plus robuste que moi,

Ce moi qui s'est de force emparé de la porte,

Ce moi qui m'a fait filer doux;

Ce moi qui le seul moi veut être,

Ce moi de moi-mème jaloux,

Ce moi vaillant, dont le courroux

Au moi poltron s'est fait connoître,

Enfin ce moi qui suis chez nous

Ce moi qui s'est montré mon maitre;

Ce moi qui m'a roué de coups."

And his conclusive decision with regard to his master:—

"Je ne me trompois pas, messieurs, ce mot termine,

Toute l'irrésolution:

Le véritable Amphitryon

Est l'Amphitryon où l'on dine."

The "Avare" has certainly faults, which a great German critic has pointed out42; but these do not interfere with the admirable spirit of the dialogue, and the humorous display of the miser's foibles. "George Dandin" was considered by his friends as a more dangerous experiment. There were so many George Dandins in the world. One in particular was pointed out to him as being at the same time an influential person, who, offended by his play, might cause its ill success. Molière took the prudent part of offering to read his comedy to him, previously to its being acted. The man felt himself very highly honoured: he assembled his friends; the play was read, and applauded; and in the sequel supported by this very person when it appeared on the stage. Poor George Dandin! there is an ingenuousness and directness in him that inspires us with respect, in spite of the ridiculous situations in which he is placed: and while Molière represents to the life the annoyances to arise to a bourgeois in allying himself to nobility, he makes the nobles so very contemptible, either by their stupidity or vice, that not by one word in the play can a rank-struck spirit be discerned. As, for instance, which cuts the most ridiculous figure in the following comic dialogue? The nobles, we think. George Dandin comes with a complaint to the father and mother of his wife, with regard to her ill-conduct. His father-in-law, M. de Sotenville (the very name is bien trouvé,—sot en ville,) asks—

"Qu'est-ce, mon gendre? vous paroissez troublé.

GEORGE DANDIN.

Aussi en ai-je du sujet; et——

MADAME DE SOTENVILLE.

Mon dieu! notre gendre, que vous avez peu de civilité, de ne pas saluer les gens quand vous les approchez!

GEORGE DANDIN.

Ma foi! ma belle-mère, c'est que j'ai d'autres choses en tête; et——

MADAME DE SOTENVILLE.

Encore! est-il possible, notre gendre, que vous sachiez si peu votre monde, et qu'il n'y ait pas moyen de vous instruire de la manière qu'il faut vivre parmi les personnes de qualité?

GEORGE DANDIN.

Comment?

MADAME DE SOTENVILLE.

Ne vous déférez-vous jamais, avec moi, de la familiarité de ce mot de belle-mère, et ne sauriez-vous vous accoutumer à me dire Madame?

GEORGE DANDIN.

Parbleu! si vous m'appelez votre gendre, il me semble que je puis vous appeler belle-mère?

MADAME DE SOTENVILLE.

Il y a fort à dire, et les choses ne sont pas égales. Apprenez, s'il vous plait, que ce n'est pas à vous à vous servir de ce mot-là avec une personne de ma condition; que, tout notre gendre que vous soyez, il y a grande différence de vous à nous, et que vous devez vous connoître.

MONSIEUR DE SOTENVILLE.

C'en est assez, m'amour: laissons cela.

MADAME DE SOTENVILLE.

Mon dieu! Monsieur de Sotenville, vous avez des indulgences qui n'appartiennent qu'à vous, et vous ne savez pas vous faire rendre par les gens ce qui vous est dû.

MONSIEUR DE SOTENVILLE.

Corbleu! pardonnez-moi; on ne peut point me faire des leçons là-dessus; et j'ai su montrer en ma vie, par vingt actions de vigueur, que je ne suis point homme à démordre jamais d'une partie de mes prétentions: mais il suffit de lui avoir donné un petit avertissement. Sachons un peu, mon gendre, ce que vous avez dans l'esprit.

GEORGE DANDIN.

Puisqu'il faut donc parler catégoriquement, je vous dirai, Monsieur de Sotenville, que j'ai bien de——

MONSIEUR DE SOTENVILLE.

Doucement, mon gendre. Apprenez qu'il n'est pas respectueux d'appeler les gens par leur nom, et qu'à ceux qui sont au-dessus de nous, il faut dire Monsieur, tout court.

GEORGE DANDIN.

Hé bien! Monsieur tout court, et nonplus Monsieur de Sotenville, j'ai à vous dire que ma femme me donne——

MONSIEUR DE SOTENVILLE.

Tout beau! Apprenez aussi que vous ne devez pas dire ma femme, quand vous parlez de notre fille.

GEORGE DANDIN.

J'enrage! Comment, ma femme n'est pas ma femme?

MADAME DE SOTENVILLE.

Oui, notre gendre, elle est votre femme; mais il ne vous est pas permis de l'appeler ainsi; et c'est tout ce que vous pourriez faire si vous aviez épousé une de vos pareilles.

GEORGE DANDIN.

Ah! George Dandin, ou t'es-tu fourré?"

But we must leave off. Sir Walter Scott says that, as often as he opened the volume of Molière's works during the composition of his article on that author, he found it impossible to lay it out of his hand until he had completed a scene, however little to his immediate purpose of consulting it; and thus we could prolong and multiply extracts to the amusement of ourselves and the reader; but we restrain ourselves, and, returning to the subject that caused this quotation, we must say, that we differ entirely from Rousseau and other critics who adopt his opinions; and even Schlegel, who accuses the author of being guilty of currying favour with rank in this comedy, and making honest mediocrity ridiculous. If genius was to adapt its works to the rules of philosophers, instead of following the realities of life, we should never read in books of honesty duped, and vice triumphant: whether we should be the gainers by this change is a question. It may be added, also, that Molière did not represent, in "George Dandin," honesty ill-used, so much as folly punished; and, at any rate, where vice is on one side and ridicule on the other, we must think that class worse used to whom the former is apportioned as properly belonging. In spite of philosophers, truth, such as it exists, is the butt at which all writers ought to aim. It is different, indeed, when a servile spirit paints greatness, virtue, and dignity on one side—poverty, ignorance, and folly, on the other.

At length the time came when Molière was allowed to bring out the "Tartuffe" in its original shape, with its original name. Its success was unequalled: it went through forty-four consecutive representations. At a period when religious disputes between molinist and jansenist ran high in France—when it was the fashion to be devout, and each family had a confessor and director of their consciences, to whom they looked up with reverence, and whose behests they obeyed—a play which showed up the hypocrisy of those who cloaked the worst designs, and brought discord and hatred into families, under the guise of piety, was doubtless a useful production; yet the "Tartuffe" is not an agreeable play. Borne away by his notion of the magnitude of the evil he attacked, and by his idea of the usefulness of the lesson, Molière attached himself greatly to it. The plot is admirably managed, the characters excellently contrasted, its utility probably of the highest kind; but Molière, hampered by the necessity of giving as little umbrage as possible to true devotees, was forced by the spirit of the times to regard his subject more seriously than is quite accordant with comedy: there is something heavy in the conduct of the piece, and disgust is rather excited than amusement. The play is still popular; and, through the excellent acting of a living performer, it has enjoyed great popularity in these days in its English dress: still it is disagreeable; and the part foisted in on our stage, of the strolling methodist preacher, becomes, by its farce, the most amusing part in the play.43

Molière may now be considered as having risen to the height of his prosperity. Highly favoured by the king, the cabals formed against him, and the enemies that his wit excited, were powerless to injure. He was the favorite of the best society in Paris; to have him to read a play, was giving to any assembly the stamp of fashion as well as wit and intellect. He numbered among his chosen and dearest friends the wits of the age. Disappointment and vexation had followed him at home; and his wife's misconduct and heartlessness having led him at last to separate from her, he endeavoured to secure to himself such peace as celibacy permitted. As much time as his avocations as actor and manager permitted he spent at his country house at Auteuil: here he reserved an apartment for his old schoolfellow, the gay, thoughtless Chapelle; here Boileau also had a house; and at one or the other the common friends of both assembled, and repasts were held where wit and gaiety reigned. Molière himself was too often the least animated of the party: he was apt to be silent and reserved in society44, more intent on observing and listening than in endeavouring to shine. There was a vein of melancholy in his character, which his domestic infelicity caused to increase. He loved order in his household, and was annoyed by want of neatness and regularity: in this respect the heedless Chapelle was ill suited to be his friend; and often Molière shut himself up in solitude.

There are many anecdotes connected with this knot of friends: the famous supper, which Voltaire tries to bring into discredit, but which Louis Racine vouches for as being frequently related by Boileau himself occurred at Molière's house at Auteuil. Almost all the wits were there except Racine, who was excluded by his quarrel with Molière. There were Lulli, Jonsac, Boileau, Chapelle, the young actor Barron, and others. Molière was indisposed—he had renounced animal food and wine, and was in no humour to join his friends, so went to bed, leaving them to the enjoyment of their supper. No one was more ready to make the most of good cheer than Chapelle, whose too habitual inebriety was in vain combatted, and sometimes imitated by his associates. On this occasion they drank till their good spirits turned to maudlin sensibility. Chapelle, the reckless and the gay, began to descant on the emptiness of life—the vain nature of its pleasures—the ennui of its tedious hours: the other guests agreed with him. Why live on then, to endure disappointment after disappointment? how much more heroic to die at once! The party had arrived at a pitch of excitement that rendered them ready to adopt any ridiculous or senseless idea; they all agreed that life was contemptible, death desirable: Why then not die? the act would be heroic; and, dying all together, they would obtain the praise that ancient heroes acquired by self-immolation. They all rose to walk down to the river, and throw themselves in. The young Barron, an actor and protégé of Molière, had more of his senses about him: he ran to awake Molière, who, hearing that they had already left the house, and were proceeding towards the river, hurried after them: already the stream was in sight. When he came up, they hailed him as a companion in their heroic act, and he agreed to join them: "But not to-night:" he said "so great a deed should not be shrouded in darkness; it deserves daylight to illustrate it: let us wait till morning." His friends considered this new argument as conclusive: they returned to the house; and, going to bed, rose on the morrow sober, and content to live.

1570.

Ætat.

40.

Among such friends—wild, gay, and witty—Molière might easily have his attention directed to farcical and amusing subjects. Some say that "Monsieur Porceaugnac" was founded on the adventure of a poor rustic, who fled from pursuing doctors through the streets of Paris: it is one of the most ridiculous as well as lively of his smaller pieces; but so excellent is the comic dialogue, that Diderot well remarks, that the critic would be much mistaken who should think that there were more men capable of writing "Monsieur Porceaugnac" than of composing the "Misanthrope." This piece has of course been adapted to the English stage; and an Irishman is burdened with all the follies, blunders, and discomfitures of the French provincial; with this difference, that the "brave Irishman" breaks through all the evils spread to catch him, and, triumphing over his rival, carries off the lady. The "Bourgeois Gentilhomme" deserves higher praise; and M. Jourdain, qualifying himself for nobility, has been the type of a series of characters, imitating, but never surpassing, the illustrious original. This play was brought out at Chambord, before the king. Louis listened to it in silence; and no voice dared applaud: as absence of praise denoted censure to the courtiers, so none of them could be amused; they ridiculed the very idea of the piece, and pronounced the author's vein worn out. They scouted the fanciful nonsense of the ballet, in which the Bourgeois is created Mamamouchi by the agents of the grand signor, and invested with a fantastic order of knighthood. The truth is, that Molière nowhere displayed a truer sense of fanciful comedy than in varying and animating with laughable doggrel and incidents the ballets that accompanied his comedies; the very nonsense of the choruses, being in accordance with the dresses and scenes, becomes wit. The courtiers found this on other occasions, but now their faces elongated as Louis looked grave: the king was mute; they fancied by sarcasm to echo a voice they could not hear. Molière was mortified; while the royal listener probably was not at all alive to the damning consequences of his hesitation. On the second representation, the reverse of the medal was presented. "I did not speak of your play the first day," said Louis, "for I fancied I was carried away by the admirable acting; but indeed, Molière, you never have written any thing that diverted me so much: your piece is excellent." And now the courtiers found the point of the dialogue, the wit of the situations, the admirable truth of the characters. They could remember that M. Jourdain's surprise at the discovery that he had been talking prose all his life, was a witty plagiarism from the count de Soissons' own lips—they could even enjoy the fun of the unintelligible mummery of the dancing Turks; and one of the noblest among them, who had looked censure itself on the preceding evening, could exclaim in a smiling ecstasy of praise: "Molière is inimitable—he has reached a point of perfection to which none of the ancients ever attained."

The "Fourberies de Scapin" followed—the play that could excite Boileau's bile; so that not all his admiration of its author could prevent his exclaiming:—

"Dans ce sac ridicule où Scapin s'envelope,

Je ne reconnais plus l'auteur du Misanthrope."

Still the comedy of tricks and hustle is still comedy, and will amuse; and there crept into the dialogue also the true spirit of Molière; the humour of the father's frequent question: "Que diable alla-t-il faire dans cette galère," has rendered the expression a proverb.

The Countess d'Escarbagnas is very amusing. The old dowager, teaching country bumpkins to behave like powdered gold-caned footmen; her disdain for her country neighbours, and glory in her title, are truly French, and give us an insight into the deep-seated prejudices that separated noble and ignoble, and Parisians from provincials, in that country before the revolution.

The "Femmes Savantes" followed, and was an additional proof that his vein not only was not exhausted, but that it was richer and purer than ever; and that while human nature displayed follies, he could put into the framework of comedy, pictures, that by the grouping and the vivid colouring showed him to be master of his art. The pedantic spirit that had succeeded to the sentimentality of les Précieuses, the authors of society, whose impromptus and sonnets were smiled on in place of the exiled Platonists of the ruelle, lent a rich harvest. "Les Femme Savantes" echoed the conversations of the select coteries of female pretension. The same spirit of pedantry existed some five and twenty years ago, when the blues reigned; and there was many a

"Bustling Botherby to show 'em

That charming passage in the last new poem."

That day is over: whether the present taste for mingled politics and inanity is to be preferred is a question; but we may imagine how far posterity will prefer it, when we compare the many great names of those days with the "small and far between" of the present. Bluism and pedantry may be the poppies of a wheat-field, but they show the prodigality of the Ceres which produces both. We are tempted, as a last extract, to quote portions of the scene in which the learned ladies receive their favourite, Trissotin, with enthusiasm, and he recites his poetry for their delight.

"PHILAMINTE.

Servez nous promptement votre aimable repas.

TRISSOTIN.

Pour cette grande faim qu'à mes yeux on expose,

Un plat seul de huit vers me semble peu de chose;

Et je pense qu'ici je ne ferai pas mal

De joindre à l'épigramme, ou bien au madrigal,

Le ragoût d'un sonnet qui, chez une princesse,

Est passé pour avoir quelque délicatesse.

Il est de sel attique assaisonné partout,

Et vous le trouverez, je crois, d'assez bon goût.

ARMANDE.

Ah! je n'en doute point.

PHILAMINTE.

Donnons vite audience.

BÉLISE (interrompant Trissotin chaque fois qu'il se dispose à lire).

Je sens d'aise mon cœur tressaillir par avance.

J'aime la poésie avec entêtement,

Et surtout quand les vers sont tournés galamment.

PHILAMINTE.

Si nous parlons toujours, il ne pourra rien dire.

TRISSOTIN.

So——

BÉLISE.

Silence, ma nièce.

ARMANDE.

Ah! laissez-le donc lire!

TRISSOTIN.

Sonnet à la Princesse Uranie, sur sa fièvre.

Votre prudence est endormie,

De traiter magnifiquement,

Et de loger superbement,

Votre plus cruelle ennemie.

BÉLISE.

Ah! le joli début.

ARMANDE.

Qu'il a le tour galant!

PHILAMINTE.

Lui seul des vers aisés possède le talent.

ARMANDE.

A prudence endormie il faut rendre les armes.

BÉLISE.

Loger son ennemie est pour moi plein de charmes.

PHILAMINTE.

J'aime superbement et magnifiquement: Ces deux adverbes joints font admirablement.

BÉLISE.

Prêtons l'oreille au reste.

TRISSOTIN.

Faites-la sortir, quoi qu'on die.

De votre riche appartement,

Où cette ingrate insolemment

Attaque votre belle vie.

BÉLISE.

Ah! tout doux, laissez-moi, de grace, respirer.

ARMANDE.

Donnez-nous, s'il vous plait, le loisir d'admirer.

PHILAMINTE.

On se sent, à ces vers, jusqu'au fond de l'âme

Couler je ne sais quoi, qui fait que l'on se pâme.

ARMANDE.

'Faites-la sortir, quoi qu'on die.

De votre riche appartement.'

Que riche appartement est là joliment dit! Et que la métaphore est mise avec esprit!

PHILAMINTE.

'Faites-la sortir, quoi qu'on die.'

Ah! que ce quoi qu'on die est d'un goût admirable, C'est, à mon sentiment, un endroit impayable.

ARMANDE.

De quoi qu'on die aussi mon cœur est amoureux.

BÉLISE.

Je suis de votre avis, quoi qu'on die est heureux.

ARMANDE.

Je voudrois l'avoir fait.

BÉLISE.

Il vaut toute une pièce.

PHILAMINTE.

Mais en comprend-on bien, comme moi, la finesse?

ARMANDE et BÉLISE.

Oh, oh!

PHILAMINTE.

'Faites-la sortir, quoi qu'on die.'

Que de la fièvre on prenne ici les intérêts;

N'ayez aucun égard, moquez-vous des caquets:

'Faites-la sortir, quoi qu'on die.

Quoi qu'on die, quoi qu'on die.'

Ce quoi qu'on die en dit beaucoup plus qu'il ne semble. Je ne sais pas, pour moi, si chacun me ressemble; Mais j'entends là-dessous un million de mots.

BÉLISE.

Il est vrai qu'il dit plus de choses qu'il n'est gros.

PHILAMINTE, à Trissotin.

Mais quand vous avez fait ce charmant quoi qu'on die. Avez-vous compris, vous, toute son énergie? Songiez-vous bien vous-mème à tout ce qu'il nous dit, Et pensiez-vous alors y mettre tant d'esprit?

TRISSOTIN.

Hai! hai!"

This scene proceeds a long time; and at length the pedant, Vadius, enters, and Trissotin presents him to the ladies.

TRISSOTIN.

"Il a des vieux auteurs la pleine intelligence,

Et sait du grec, madame, autant qu'homme de France.

PHILAMINTE.

Du grec! O ciel! du grec! il sait du grec, ma sœur.

BÉLISE.

Ah, my nièce, du grec!

ARMANDE.

Du grec! quelle douceur!

PHILAMINTE.

Quoi! monsieur sait du grec? Ah! permettez, de grace,

Que, pour l'amour du grec, monsieur, on vous embrasse."

The pedants at first compliment each other extravagantly, and then quarrel extravagantly; and Vadius exclaims,—

"Oui, oui, je te renvoie à l'auteur des Satires.

TRISSOTIN.

Je t'y renvoie aussi.

VADIUS.

J'ai le contentement

Qu'on voit qu'il m'a traité plus honorablement.

* * * *

Ma plume t'apprendra quel homme je puis être.

TRISSOTIN.

Et la mienne saura te faire voir ton maître.

VADIUS.

Je te défie en vers, en prose, grec et latin.

TRISSOTIN.

Eh bien! nous nous verrons seul à seul chez Barbin."