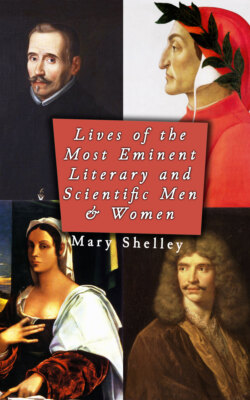

Читать книгу Lives of the Most Eminent Literary and Scientific Men & Women (Vol. 1-5) - Mary Shelley - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1483-1553

ОглавлениеFrancis Rabelais,—"the great jester of France," as he is designated by Lord Bacon; a learned scholar, physician, and philosopher, as he appears from other and eminent testimonies,—was one of the most remarkable persons who figured in the revival of letters. It is his fortune, like the ancient Hercules, to be noted with posterity for many feats to which he was a stranger,—but which are always to his disadvantage. The gross buffooneries amassed by him in his nondescript romance have made his name a common mark for any extravagance or impertinence of unknown or doubtful parentage. The purveyors of anecdotes have even fixed upon him some of the lazzi, as they are called, which may be found in the stage directions of old Italian farce. Those events and circumstances of his life which are really known, or deserving of belief, may be given within a narrow compass. We, of course, reject, in this notice, all that would offend the decencies of modern and better taste.

Rabelais was born at Chinon, a small town of Touraine. The date of his birth is not ascertained; but the generally received opinion of his death, at the age of 70, in 1553, would place his birth in 1483. There is the same uncertainty respecting the condition of his father; whether that of an innkeeper or apothecary. His predilection for the study of medicine favours the latter supposition, whilst the imputed habits of his life countenance the former. If, however, he was really abandoned to intemperance, as he is represented by his adversaries, who were many and unscrupulous, it may, with equal propriety, be charged to his monastic education, at a time when cloisters were the chosen seats of debauchery and ignorance.

He received his first rudiments at the convent of Seville, near his native town, where his progress was so slow that he was removed to another in Angiers. Here also his career seemed unpromising; and the only advantage he derived was that of becoming known to the brothers Du Bellay, one of whom, afterwards bishop of Paris and cardinal, was his patron and friend through life.

From Angiers he passed to a convent of cordeliers at Fontenaye-le-Compte, in Poitou. He now applied himself, for the first time, to the cultivation of his talents, but under circumstances the most unfavourable. The cordeliers of Fontenaye-le-Compte had no library, or notion of its use. Rabelais assumed the habit of St. Francis, distinguished himself by his preaching, and employed what he received for his sermons and masses in providing himself with books. The animosity of his brother monks was excited against him: they envied and hated him, for his success as a preacher, and for his superior attainments;—but his great and crying sin in their eyes was his knowledge of Greek, the study of which they denounced as an unholy and forbidden art. This was perfectly consistent: they were content with Latin enough to give them an imposing air with the multitude; some did not know even so much, and, instead of a breviary, carried a wine flask exactly resembling it in exterior form.

His brother monks annoyed and harassed Rabelais by all the modes which malice, ignorance, and numbers can employ against an individual, and in a convent. The learned Budeus11, alluding to the persecutions which he was suffering, says, in one of his letters, "I understand that Rabelais is grievously annoyed and persecuted, by those enemies of all that is elegant and graceful, for his ardour in the study of Greek literature. Oh! evil infatuation of men whose minds are so dull and stupid!" They at last condemned him to live in pace; that is to linger out the remainder of his life, on bread and water, in the prison cell of the convent.

The cause, or the pretence, of Rabelais's being thus buried alive, is described as "a scandalous adventure:" but differently related. According to some the scandal consisted in his disfiguring, by way of frolic, in concert with another young cordelier, the image of their patron saint. Others state, that on the festival of St. Francis he removed the image of the saint, and took its place. Having taken precautions to hear out the imposture, he escaped detection, until the grotesque devotions of the multitude, and the rogueries of the monks, overcame his gravity, and he laughed. The simple people, seeing the image of the saint, as they supposed it, move, exclaimed, "A miracle!" but the monks, who knew better, dismissed the laity, made their false brother descend from his niche, and gave him the discipline, with their hempen cords, until his blood appeared. We will not decide which, or whether either, of these versions be true; but it is certain that he was condemned, as we have said, to solitary confinement for life in the prison cell.

Fortunately for him, his wit, gaiety, and acquirements had made him friends who were powerful enough to obtain his release. These were the Du Bellays already mentioned, and Andre Tiraqueau, chief judge of the province, to whom one of Rabelais's Latin letters is addressed;—a man of learning, it would appear, and an upright judge. The letter is addressed, "Andreo Tiraquello, equissimo judici, apud Pictones," and commences "Tiraquello doctissime." Their influence obtained not only his liberty, but the pope's (Clement VII.) licence to pass from the cordeliers of Fontenaye-le-Compte, to a convent of Benedictines at Maillezieux in the same province. This latter order has been distinguished for learning, and deserves respectful and grateful mention for its share in the preservation of the classic remains of antiquity. It was, no doubt, more agreeable, or less disagreeable, to Rabelais than that which he had left; but wholly disgusted with the monastic life, he soon threw off the frock and cowl, left the convent of his own will and pleasure, without licence or dispensation from his superiors, and for some time led a wandering life as a secular priest.

We next find him divested wholly of the sacerdotal character; and studying medicine at Montpelier. The date of this transition, as too frequently happens in the life of Rabelais, cannot be determined. He, however, pursued his studies, took his successive degrees of bachelor, licentiate, and doctor, and was, after some time, appointed a professor. He lectured, it appears from his letters of a subsequent date, chiefly on the works of Hippocrates and Galen. His superior knowledge of the Greek language enabled him to correct the faults of omission, falsification, and interpolation, committed by former translators of Hippocrates; and he executed this task, he says, by the most careful and minute collation of the text with the best copies of the original. "If this be a fault," says he, speaking of preceding mistranslations, "in other books, it is a crime in books of medicine; for in these the addition or omission of the least word, the misplacing even of a point, compromises the lives of thousands." Accordingly, his edition of Hippocrates, subsequently published by him at Lyons, has been highly prized by physicians and scholars.

Rabelais had less difficulty in restoring and elucidating the text, than in bringing into practice the better medical system of the father of the art. He complains, in his Latin epistle to Tiraqueau, at some length, but in substance, that though the age boasted many learned and enlightened men, yet the multitude was in worse than Cimmerian darkness—the many so besotted by the errors, however gross, which they had first imbibed, and by the books, however absurd, which they had first read, as to seem irremediably blind to reason and truth—clinging to ignorance and absurdity, like those shipwrecked persons who trust to a beam or a rag of the vessel which had split, instead of making aneffort themselves to swim, and finding out their mistake only when they are hopelessly sinking.—Mountebanks and astrologers (he adds) were preferred to learned physicians, even by the great.

But his capacity and zeal were held in just estimation by the medical faculty of Montpelier.—The chancellor Duprat having, for some reason now unknown, deprived that body of its privileges, or, according to Nicéron, one college only having suffered deprivation, Rabelais was deputed to solicit their restoration. There is a current anecdote of the strange mode which he took to introduce himself to the chancellor.—Arrived at the chancellor's door, he spoke Latin to the porter, who, it may be supposed, did not understand him; a person who understood Latin presenting himself, Rabelais spoke to him in Greek; to a person who understood Greek, he spoke Hebrew; and so on, through several other languages and interpreters, until the singularity of the circumstance reached the great man, and Rabelais was invited to his presence. This is in the last degree improbable. Cardinal du Bellay, his patron, was then bishop of Paris, in high favour at the court of Francis I., and, doubtless, ready to present him in a manner much more conducive to the success of his mission. The ridiculous invention was suggested by a passage of Rabelais, in which Panurge addresses Pantagruel, on their first meeting, in thirteen different languages, dead and living, not including French. Rabelais, however, pleaded the cause of the faculty of Montpelier so well, that its privileges were restored, and he was received by his colleagues on his return with unprecedented honours. So great was the estimation in which he was held henceforth, and the reverence for him after his departure, that every student put on Rabelais's scarlet gown when taking his degree of doctor. This curious usage continued from the time of Rabelais down to the Revolution. The gown latterly used was not the identical one of Rabelais. The young doctors, in their enthusiasm for its first wearer, carried off each a piece, by way of relic, until, in process of time, it reached only to the hips, and a new garment was substituted.

Rabelais, having left Montpelier, appears next at Lyons, where he practised as a physician, and published his editions of Hippocrates and Galen, with some minor pieces, including almanacks, which prove him conversant with the science of astronomy. One almanack bearing his name is pronounced spurious, on the ground of his being made to describe himself as "physician and astrologer." He treated the pretended science of astrology with derision. This would add nothing to his reputation in a later age; but, considering the number of his contemporaries, otherwise enlightened, who were not proof against this weakness, it proves him to have been one of those superior spirits whose views are in advance of their generation.

Cardinal du Bellay was sent ambassador by Francis I. to the court of Rome in 1534, and attached Rabelais as physician to his suite. He appears to have made two visits to Italy with the cardinal at this period, but there are no traces by which they can be distinguished, nor is it very material. It is made a question in one of the most recent sketches of the life of Rabelais, whether he attended the ambassador as physician or buffoon. His letters, addressed from Rome, to his friend the bishop of Maillezieux, furnish decisive evidence of his being a a person treated with respect and confidence, independently of the known friendship of the cardinal. They are the letters of a man of business, well informed of all that was passing, and trusted with state secrets. He alludes, in one letter, to the quarrels of Paul III. (now pope) and Henry VIII. It appears that the cardinal du Bellay and the bishop of Mâcon opposed and retarded, in the consistory, the bull of excommunication against Henry, as an invasion of the rights and interests of Francis I. Writing of the pope, and to a bishop, he treats him as a temporal prince, with the freedom of one man of sense and frankness writing to another, but without the least approach to levity.

We pass over the gross and idle buffooneries which Rabelais is said to have permitted himself at his first audience of the pope, and towards his person. They are too coarse to be mentioned, and too inconsistent with the probabilities of place and person to be believed. One anecdote only may be excepted, as not altogether incredible. The pope, it is said, expressed his willingness to grant Rabelais a favour, and he, in reply, begged his holiness to excommunicate him. Being asked why he preferred so strange a request, he accounted for it by saying, that some very honest gentlemen of his acquaintance in Touraine had been burned, and finding it a common saying in Italy, when a faggot would not take fire, that it was excommunicated by the pope's own mouth, he wished to be rendered incombustible by the same process. Rabelais appears to have indulged and recommended himself by his writ and gaiety at Rome; and it is not absolutely incredible that he may have gone this length with Paul III., who was a bad politician rather than a persecutor. But it is still unlikely, that whilst he was soliciting absolution from one excommunication, which he had already incurred by his apostacy from his monastic vows, he should request the favour of another, even in jest. It appears untrue that he gave offence by his buffooneries, and was punished or disgraced. This assertion is negatived by his letters, and, more conclusively, by the pope's granting him the bull of absolution, which he had been soliciting for some time.

Rabelais returned to Lyons after his first visit to Rome. After the second, he appears to have gone to Paris. No credit is due to the ridiculous artifice by which, it has been stated so often in print, he got over the payment of his hotel bill at Lyons, and travelled on to Paris at the public charge. He made up, it is pretended, several small packets, and employed a boy, the son of his hostess, to write on them "poison for the king," "poison for the queen," &c. through the whole royal family. His injunctions of secrecy of course ensured the disclosure of the secret by the young amanuensis to his mother, and Rabelais was conveyed a state prisoner to the capital. Arrived at Paris, and at court too, he proved the innocuous quality of his packets, and amused Francis I. by swallowing the contents. It has been justly remarked by Voltaire, that at a moment when the recent death of the dauphin had taken place under the suspicion of poison, this freak would have subjected Rabelais to be questioned upon the rack. Other ridiculous expedients, said to have been used by him, to extricate himself from his tavern bills, when he was without money to pay them, are undeserving of notice. There is no good evidence of his having been at any time under the necessity of resorting to them. His letters from Rome to the bishop of Maillezieux, of whom he was the pensioner, make it appear that his mode of life there was frugal and regular. But the common source of all these impertinent fictions is the mistake, as we have already said, of confounding an author with his book. Rabelais, the eulogist of debts and drunkenness, the high priest of "the oracle of the holy bottle," must of course have been reduced to such expedients! There cannot be a greater error. Doctor Arbuthnot, who approached the broad humour of Rabelais, even nearer than Swift, was remarkable for the gravity of his character and deportment.

Cardinal du Bellay, on his return from Rome to Paris, took Rabelais into his family, as his physician, his librarian, his reader, and his friend. It is stated, that he confided to him even the government of his household; which is itself a proof that Rabelais was not the reckless, dissolute buffoon he is represented. The cardinal's regard for him did not rest here. He obtained from the pope a bull, which secularized the abbey of St. Maur-des-Fosses, in his diocese of Paris, and conferred it on Rabelais. The next favour bestowed upon Rabelais by his patron was the cure or rectory of Meudon, which he held to his death, and from which he is familiarly styled "Le curé de Meudon."

It is not known at what periods or places Rabelais wrote his "Lives of the great Giant Garagantua and his Son Pantagruel;" to which he owes, if not all his reputation, certainly all his popularity; but he appears to have completed and republished it after his return from Italy. The date of the earliest existing edition of the first and second books is 1535; but there were previous editions, which have disappeared. The "Champ Fleury," of Geoffroy Tory, quoted by Lacroix du Maine, refers to them as existing before 1529. The royal privilege, dated 1545, granted by Francis I. to "our well-beloved Master Francis Rabelais," for reprinting a correct and complete edition of his work, sets forth that many spurious publications of it had been made; that the book was useful and delectable and that its continuance and completion had been solicited of the author "by the learned and studious of the kingdom."

The book and the author were attacked on all sides, and from opposite quarters. The champions for and against Aristotle, who disputed with a sectarian animosity, equalling in fury the theological controversies of the time, suspended their warfare to turn their arms against Rabelais; he was assailed, as a common enemy, by the champions of the Romish and reformed doctrines; by the anti-stagyrite Peter Ramus, and his antagonist Peter Gallandus; by the monk of Fontevrault, Puits d'Herbault, and by Calvin. But the most formidable quarter of attack was the Sorbonne, and its accusations against him the most perilous to which he could be exposed—heresy and atheism. The book was condemned by the Sorbonne, and by the criminal section of the court of parliament.

When it is considered that Rabelais, in the sixteenth century, and in France, chose for the subjects of his ridicule and buffoonery the wickedness and vices of popes, the lazy luxurious lives and griping avarice of the prelates, the debauchery, libertinism, knavery, and ignorance of the monastic orders, the barbarous and absurd theology of the Sorbonne, and the no less barbarous and absurd jurisprudence of the high tribunals of the kingdom, the wonder is not that he was persecuted, but that he escaped the stake. His usual good fortune and high protection, however, once more saved him. Francis I. called for the obnoxious and condemned book, had it read to him from the beginning to the end, pronounced it innocent and "delectable," and protected the author. The sentence of condemnation became a dead letter, the book was read with avidity, and Rabelais admired and sought as the first wit and scholar of his age.

Some expositors of Rabelais will have it, that his romance is the history of his own time burlesqued. The fictitious personages and events have even been resolved into the real. Nothing can be more uncertain, or indeed more improbable. The simple fact, that of two the most copious and diligent commentators of Rabelais,—Motteux and Duchat,—one has identified Rabelais's personages with the D'Albrets of Navarre, Montluc bishop of Valence, &c., whilst the other has discovered in Grandgousier, Garagantua, Pantagruel, Panurge, friar John, the characters of Louis XII., Francis I., Henry II., cardinal Lorraine, cardinal du Bellay. This fact alone proves the hopeless uncertainty of the question. Passing over the glaring want of congruity, which any reader of history and of Rabelais must observe between the personages here identified, how improbable the supposition that Rabelais should have held up to public ridicule the sovereign who protected him, and the friend upon whom he was mainly dependant! How absurd the supposition that neither of them should have discovered it, or been made sensible of it by others! We more particularly notice this baseless hypothesis,—for such it really is,—because it is the most confidently and frequently reproduced.

But, independently of what we have said, there is an outrageous disregard of all design and probability in the work, which defies any such verification. The most reasonable opinion, we think, is, that Rabelais attached himself to no series of events, and to no particular persons, but burlesqued classes and conditions of society, and even arts and sciences, as they presented themselves to his wayward humour and ungoverned or ungovernable imagination. This view is borne out by what we read in the memoirs of the president De Thou, who describes the author and the book as follows:—"Rabelais had a perfect knowledge of Greek and Latin literature, and of medicine, which he professed. Discarding, latterly, all serious thoughts, he abandoned himself to a life of gaiety and sensuality, and, to use his expression, embracing as his own the art of ridiculing mankind, produced a book full of the mirth of Democritus, sometimes grossly scurrilous, yet most ingeniously written, in which he exhibited, under feigned denominations, as on a public stage, all orders of the community and of the state, to be laughed at by the public."

Perhaps the real secret of his enigmatical book may be found on the surface, in his own declaration,—that he wrote for the amusement of his patients, and of the sick and sad of mankind, "those jovial follies (cez folastreries joyeuses), whilst taking his bodily refreshment, that is, eating and drinking, the proper time for treating matters of such high import and profound science."

The charge of heresy, as understood by the church of Rome, could be easily proved against him; but there appears no good ground for that of atheism, or of infidelity. He applies texts of Scripture improperly and indecently, but rather from wanton levity of humour than deliberate profaneness; and he may have retained this part of his early habits as a cordelier,—for the monks were notorious for the licence with which they applied, in their orgies, the texts of Scripture in their breviaries,—probably the only portions of Scripture which they knew: allowance is also to be made for the tone of manners and language in an age when the most zealous preachers and theologians, Romish and reformed, indulged in profane applications and parodies of Scripture without reproach. Rabelais was in principle a reformer, but of a humour too light and careless to embark seriously in the great cause.

No writer has had more contemptuous depreciators and enthusiastic admirers: his book has been called a farrago of impurity, blasphemy, and trash; a masterpiece of wit, pleasantry, erudition, and philosophy, composed in a charming style. An unqualified judgment for or against him would mislead. The most valuable opinions of him are those of his own countrymen, since the French language and literature have attained their highest cultivation. Labruyere, after discarding the idea of any historic key to Rabelais, says of him, that "where he is bad, nothing can be worse, he can please only the rabble; where good, he is exquisite and excellent, and food for the most delicate." Lafontaine, who in his letters calls him "gentil Maitre Français," has versified several of his tales, and even imitated his diction. Boileau called him "reason in masquerade" (la raison en masque). Bayle, however, made so light of him, that he has not deigned him an article in his dictionary, and only names him once or twice in passing. This was surely injustice from one who gives a separate and copious notice to the buffoon and bigot. Father Garasse. Voltaire has treated Rabelais contemptuously; called him "a physician playing the part of Punch," "a philosopher writing in his cups," "a mere buffoon." But these opinions, expressed in his philosophical letters, were recanted by him, after some years, in a private letter to Madame du Deffand; and he avows in it that he knew "Maitre Français" by heart. Voltaire appropriated both the matter and manner of Rabelais in some of his tales and "facéties," and he has been accused of this petty motive for decrying him. It was discovered, at the French revolution, that Rabelais was another Brutus, counterfeiting folly to escape the despotism of which he meditated the overthrow; and the late M. Ginguené proved, in a pamphlet of two hundred pages, that Rabelais anticipated all the reforms of that period in the church and state.

The detractors of Rabelais's book may be more easily justified than his admirers. The favour which it obtained in his lifetime, and the popularity which it has maintained through three centuries, may be ascribed to other causes besides its merits. It had the attraction of satire, malice, and mystery, which all were at liberty to expound at their pleasure; and many, doubtless, read it for its ribald buffooneries. There is in it, at the same time, a fund of wit, humour, and invention—a rampant, resistless gaiety, which gives an amusing and humorous turn to the most outrageous nonsense. There are touches of keen and witty satire, which bear out the most favourable part of the judgment of Labruyere. The condemnation of Panurge, who is left to guess his crime, is most happily humorous and satirical, whether applied to the Inquisition or to the barbarous jurisprudence of the age. Panurge protests his innocence of all crime: "Ha! there!" exclaims Grippe-Menaud; "I'll now show you that you had better have fallen into the claws of the devil than into ours. You are innocent, are you? Ha! there! as if that was a reason why we should not put you through our tortures. Ha! there! our laws are spiders' webs; the simple little flies are caught, but the large and mischievous break through them." There is in Rabelais a variety of erudition, less curious than Butler's, but more elegant. His stock of learning, it has been said, would be indigence in later times: but it should be remembered at how little cost a great parade of erudition may now be made out of indexes and encyclopedias, whilst Rabelais, Erasmus, and the other scholars of their time, had to purvey for themselves.

Rabelais most frequently quotes; but he also appropriates sometimes, without acknowledgment, what he had read. Some of his tales are to be found in the "Facetiæ" of Poggius;—that, for instance, which has been versified by Lafontaine and Dryden: and he applied to himself, after Lucian (in his treatise of the manner of writing history), the story of Diogenes rolling his tub during the siege of Corinth. Lucian has been called his prototype. Their essentially distinctive traits may be seen at a glance in their respective uses of this anecdote of the cynic philosopher: in the redundant picturesque buffoonery of dialogue and description of the one; the felicity, humour, severer judgment, and chaster style of the other.

It is impossible to characterise the fantastic cloud of words, so far beyond any thing understood by copiousness or diffuseness, conjured up sometimes by Rabelais; his vagrant digressions, astounding improbabilities, and monstrous exaggerations: but he has that rare endowment which all but redeems these faults, and charms the reader,—the talent of narrating. His great and fatal blemish is his grossness, his disregard of all decency, his sympathy with nastiness, his invasion of all that is weak and vile in the recesses of nature and the imagination. But it should be said for him, at the same time, that his is the coarseness which revolts, rather than the depravity which contaminates; and not only his affectation of a diction more antique than even his own age, but his use of the vulgar provincialisms called in France Patois, limit his popularity in the original to readers of his own country, and the better informed of other countries.

Rabelais had a host of imitators in his own age, and that which immediately succeeded: they have all sunk into utter and just oblivion, with the exception, perhaps, of Beroalde de Verville, author of the "Moyen de Parvenir." Scarron more recently made Rabelais his model, with a congenial taste for buffoonery and burlesque. Molière has not disdained to borrow from him in his comedies. Lafontaine has versified several of the tales introduced in his romance, and has even inclined to his diction. Swift has condescended to be indebted to him. "Gulliver's Travels" and the "Tale of a Tub" both bear decisive evidence, not only in particular passages, but in their respective designs, of the author's being well acquainted with the romance of "Garagantua and Pantagruel." But the imitations only prove Swift's incomparable superiority of judgment and genius. No two things can be more different, than the grave and governed humour of Swift, and the laughing mask of everlasting buffoonery worn by Rabelais: both employ in their fictions the mock-marvellous and gigantic; but Swift observes, throughout, a proportioned scale in his creations, whilst Rabelais outrages all proportion and probability: for instance, in his absurd yet laughable fiction of Panurge's six months' travels, and his discovery of mountains, valleys, rocks, cities, in the mouth of the great giant Pantagruel. Sterne's "Tristram Shandy" is more closely modelled upon the romance of Rabelais. There is the same love of farce, whim, and burlesque, even to the theology of the schoolmen; the same love of digression and wandering: but in Sterne, a superior finesse of perception and expression, the relief of mirth and pathos intermingled, and, above all, a tone of finer humanity.

Rabelais left, besides his romance, "Certain Books of Hippocrates;" and "The Ars Medicinalis of Galen," revised, edited, and commented by him; "The Second Part of the Medical Epistles of Manardi, a physician of Ferrara," edited and commented; "The Will of Lucius Cuspidius;" and "A Roman Agreement of Sale—venerable Remains of Antiquity:" (Rabelais was deceived—they were forgeries: the one by Pomponius Lætus; the other by Pontanus, whom Rabelais, on discovering his mistake, gibbeted in his romance). "Marliani's Topography of Ancient Rome," merely republished by him; "Several Almanacks, calculated under the Meridian of the noble City of Lyons;" "Military Stratagems and Prowess of the renowned Chevalier de Langey," a relative of his patron cardinal du Bellay (doubtful whether his); "Letters from Italy, addressed to the Bishop of Maillezieux," with a historical commentary, far exceeding the bulk of the text, by the brothers St. Marthe; "La Sciomachie" (sham battle)—a description of the fête given at Rome by cardinal du Bellay, in honour of the birth of the duke of Orleans, son of Francis I.; "Epistles," in Latin prose and French verse; "Smaller Pieces" of French poetry; "The Pantagrueline Prognostication," connected with the romance; and "The Philosophical Cream," a burlesque on the disputations of the schoolmen and the Sorbonne.

"The heroic Lives of the great Giants Garagantua and Pantagruel" have gone through countless editions, various expurgations, and endless commentaries; but the most valuable or curious are Duchat's, with a historical and critical commentary, in French; Motteux's, with similar commentaries, in English; an edition by the bookseller Bernard, of Amsterdam, in 1741, with the annotations of the two former, revised and criticised, and illustrations of the text engraved from drawings by Picart; an edition, in three volumes, Paris, 1823, with a copious glossary, a curious and highly illustrative table of contents, and "Rabelæsiana," collected from the author's book, not from his life; another Paris edition, of the same date, in nine volumes, with a "variorum" commentary, from the earliest annotators down to Ginguené, valuable from its copiousness rather than discernment. This last edition gives the 120 wood-cut Pantagruelian caricatures, first published in 1655, under the title of "Songes drolatiques," and ascribed, upon questionable grounds, to Rabelais.

It has been said, with every appearance of truth, that the conversation and character of Rabelais were greatly superior to his book. He knew fourteen languages, dead and living, including Hebrew and Arabic, and wrote Greek, Latin, and Italian. The Greek which he puts into the mouth of Panurge, though not the purest, even for a modern, is fluent and correct. We may remark, in passing, that the Greek word "αὐτὸ" given as part of the text in the common character, is written "afto." He was conversant with all the sciences and most of the arts of his time: a physician, a naturalist, a mathematician, an astronomer, a theologian, a jurist, an antiquary, an architect, a grammarian, a poet, a musician, a painter. His person and deportment are described as noble and graceful, his countenance engaging and expressive, his society agreeable, his disposition generous and kind. He was the physician as well as pastor of his parishioners at Meudon, where he passed his time between the society of men of letters and his friends, his clerical and medical duties, and teaching the children who chanted in the choir the elements of music. He died, it is supposed, in 1553, at the age of seventy, in Paris, and was buried in the churchyard of St. Paul, Rue des Jardins, at the foot of a tree, which, out of respect to his memory, was religiously spared, until it disappeared by natural decay.

It is untrue that he sent to cardinal du Bellay, from his deathbed, this idle message, by a page whom the cardinal had sent to know his state—"Tell the cardinal I am going to try the great 'perhaps'—you are a fool—draw the curtain—the farce is done;" or that he made this burlesque will,—"I have nothing—I owe much—I leave the rest to the poor;" or that he put on a domino when he felt his death approaching, because it is written, "beat! qui moriuntur in Domino." They are impertinent fictions. Duverdier (quoted by Nicéron in his Literary Memoirs, vol. XXXII.) had spoken ill of Rabelais in his "Bibliothèque Française," but retracted in his "Prosographie," and bore testimony to the Christian sentiments in which he died.

No monument has been placed over the grave of Rabelais, but he has been the subject of many epitaphs. We select two of them; one in Latin, the other in French:—

Ille ego Gallorum Gallus Democritus, ill.

Gratius, aut si quid Gallia progenuit.

Sic homines, sic et cœlestia Numina lusi,

Vix homines, vix ut Numina læsa putes.

Pluton, prince du sombre empire,

Ou les tiens ne rient jamais,

Reçois aujourd'hui Rabelais,

vous aurez, tous, de quoi rire.

11. Guillaume Budé.