Читать книгу A House in St John’s Wood: In Search of My Parents - Matthew Spender, Matthew Spender - Страница 10

3 SUICIDE OR ROMANTICISM

ОглавлениеIN THE SPRING of 1933, near Piccadilly Circus, a few weeks after he’d published his first volume of poems with Faber, Stephen met Tony Hyndman. The book had placed Stephen firmly in the limelight and critics were beginning to pay attention to a whole new school of young British poets. He was full of confidence and, in his usual impetuous way, Stephen immediately invited Tony to come and live with him. They were together for the next six years; and at some level they remained attached to each other for the rest of Tony’s life.

I take the view that Stephen’s desire to live openly with Tony in the early Thirties was a brave attempt for the time. If the affair failed, it was because Tony couldn’t reach the role that Stephen had imagined for him. Though he was quick and sharp about London literary gossip, he was unable to become a serious person. The initial attraction of Tony was, of course, the opposite of this. He was down to earth, humorous, light-hearted. But since he never changed, since he couldn’t learn to love Mozart or Michelangelo (as it were), my father lost his temper. By the time he ran off to fight in Spain, Tony had become ‘the son whom I attempted to console, but of whom I was the maddening father’.

I remember Tony from my childhood, when he was not much older than forty. He spoke with a slight Welsh lilt and was cheerful to look at, with curly brown hair and a friendly smile. My father employed him in the garden whenever he was desperate for cash, which was often. Tony was full of compliments for my small self but touchy about his relationship with Stephen, which he implied had included a wealth of experience that had nothing to do with Mummy or me. This wasn’t clear to me at the age of eight, but by the age of twelve I’d noticed that Tony wasn’t a real handyman. He was too knowing.

Years later when he was planning his autobiography, Tony wrote that it must have been fate that had brought them together. ‘To me, from the moment I left Hyde Park Corner I was alone. Every step towards the Circus, each pause at a shop window in case some gent might pick me up, all the moments of time, step and pace led me to you.’

They moved into Stephen’s small flat in St John’s Wood. After less than a fortnight they left England and toured Europe: Paris, Florence, Rome, then northwards to Levanto on the coast between Tuscany and Liguria. There, in a palm-secluded hotel above the sea, they went through their first major confrontation. Tony mentions it twice in his memoirs. ‘In Levanto where I wept because suddenly all my resistance went. There was the urge to give, not to take; to protect instead of protection.’ And again: ‘What happened was inevitable, having got so far. “Will we always be friends” said Stephen one night: I broke down: never given myself to anyone before: it was complete: I wept with relief.’

Stephen remembered this occasion differently. According to him Tony said, ‘I want to go away. You are very nice to me, but I feel that I am becoming completely your property. I have never felt like that before with anyone, and I can’t bear it.’ He probably expected Stephen to beg him to stay, but instead Stephen said he was free to go, if that’s what he wanted. They’d meet again in London, perhaps. However, ‘by saying this, I had deprived him of any reason for wishing to leave’.

In those days, working-class boys who lived with some ‘gent’, as Tony put it, assumed identities that had been worked out for them since time immemorial. They learned these roles in the bars and the barracks and the Lokalen where boys congregated. Gerhart Meyer, Auden’s lover in Berlin, was a ‘tough’ boy. Harry Giese was the ‘reliable ox’ who wanted to be cared for. Hellmut Schroeder was a ‘broken wing’ boy, the misunderstood genius; and Stephen had followed the fantasy as far as it could go, given that Hellmut didn’t actually produce anything. These roles formed a protective shell to disguise the fact that the ‘boy’ was in a subordinate position. It was a matter of pride. That’s why, after Tony collapsed in Levanto, he never forgot. He’d revealed once and for all that he was Stephen’s dependant. No amount of reassurance from Stephen could eradicate this mistake.

If you have a wide education you don’t mind being humiliated, because you have nothing to lose. Everything important is in your head where nothing can get at it – as Stephen had realized when he’d been robbed in Hamburg. Even something as humiliating as scrubbing lavatories in jail won’t affect your capacity to think, but if you are aiming to improve your social status, the faintest trace of public humiliation raises questions about rank and respect. Tony’s position is therefore, to me, more poignant than Stephen’s. And Stephen’s generous offer of equality to Tony was self-delusional. It merely underlined the fact that Tony was not Stephen’s equal.

Yet there was something in this unexpected confrontation that broke an inhibition in Stephen as well. He was made to realize that he could, after all, communicate with Tony in spite of the difference of class. This had never happened so far. As he wrote to Isaiah: ‘When I was first here the very fact that I was with someone whose difference from me I had to accept & recognize made things very painful for me. Because till now I have always had that kind of relationship with people who were tarts or sneaks or liars or something, & all that was required from me was an attitude. This is quite different & was at first less noble and more difficult. However now we are both reaping the fruits.’

Back in London in the early summer of 1933, they tried to create an identity as a couple before their friends came back from their holidays. Tony looked for a new flat or printed photographs in the kitchen of their rented rooms or did the housework. Stephen wrote to Lincoln Kirstein, the editor of the American magazine Hound and Horn, for which he’d contributed some poems and articles: ‘I feel more & more happy with Tony & we are much surer of each other than before. Often with him I have a feeling that I have now everything that I’ve ever wanted out of life & am completely satisfied: I also feel often as if I would like to stop now & not go on.

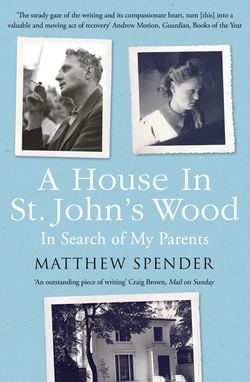

Tony swimming in Lake Garda in the summer of 1936.

They found a new flat on Randolph Crescent, in Maida Vale. Then Tony went off to Wales to visit his family. ‘It’s horrid not having you about to kiss every hour while your [you’re] tidying the place up,’ Stephen wrote to him. ‘But it is lovely to look forward to our life together again.’ He loved being with Tony. He wrote to Kirstein, ‘He is one of those lucky people who knows he needs love all the time and who can accept it.’

Their existence as a couple was noticed by Virginia Woolf. ‘I see being young is hellish. One wants to cut a figure. He [Stephen] is writing about Henry James and has tea alone with Ottoline [Morrell] and is married to a Sergeant in the Guards. They have set up a new quarter in Maida Vale; I propose to call them the Lilies of the Valley. There’s William Plomer, with his policeman; then Stephen, then Auden and Joe Ackerly, all lodged in Maida Vale, and wearing different coloured Lilies.’ The reference is to Oscar Wilde, who was often depicted holding a lily.

Stephen had met the South African novelist William Plomer while he was still at Oxford. Joe Ackerley went on to become the editor of the Listener, where he frequently commissioned articles from his friends. Virginia Woolf was right to detect something conspiratorial in the vision of all these male couples living openly together, but she was amused rather than shocked – though maybe there’s an element of snobbery in there somewhere.

As soon as he thought he had a satisfactory draft, my father showed her a typescript of The Temple. Perhaps it was his way of proving that this particular Lily of Maida Vale was serious. She gave it her full attention on more than one occasion, but she did not think that it worked. The Temple includes a sex scene between two men, but that was not the reason why she told him the book should be abandoned. Virginia Woolf was not shockable in that way, however sensitive her literary persona might seem. Sex was an aspect of freedom; therefore it should not suffer any puritanical restrictions. As a subject, however, sex disturbed her. My father told me that he’d asked her once how important in a relationship she thought sex was. She said: ‘It depends how highly you value cocks and cunts.’ She had not dodged the question. She’d merely killed the subject.

In the spring of 1934, Stephen and Tony travelled to Yugoslavia via Venice and Trieste. By the middle of the month they were settled in a pension in Mlini, a small fishing village not far from Dubrovnik. The hotel’s other clients were Nazi holidaymakers, but apart from that, it was a peaceful place where Stephen could work.

One day, there turned up at their hotel an American woman with her daughter, plus her daughter’s nurse. The woman was Muriel Gardiner, a young psychiatrist studying in Vienna with a pupil of Freud. She and Stephen made friends. She told him about the suppression of the workers in Vienna early in the year. She’d been there. She could provide an eyewitness account – which Stephen incorporated into Vienna, a long poem that tries to blend politics and personal experience into one narrative, in order to make the point that in this particularly dark period of Germany’s history private lives and public disasters were becoming inextricably tangled.

In Vienna a few weeks later, while Tony was recovering from an operation for appendicitis, Stephen and Muriel began to have an affair.

To Christopher Isherwood he wrote: ‘I find the actual sex act with women more satisfactory, more terrible, more disgusting, and in fact more everything. To me it is much more of an experience, I think, and that is all there is to it.’ This draws a line between himself and Christopher, who’d never had such doubts about his sexual identity. But there’s a curious aspect to ‘normal’ sex. ‘The effect is funny, because I find boys much more attractive, in fact I am more than usually susceptible.’

This is honest, but it’s also strange. He loved Muriel, but a magnet drew him in the other direction. And Tony? Wasn’t he the steadiest relationship at the moment?

He wrote about his confusion to William Plomer: ‘As a “character” I am no good. I realized that when I saw that I was capable of feeling just the same about Tony, & being attracted by a woman, and wanting to go with miscellaneous boys. Obviously if I’m like that my relationship with Tony becomes the thing that is most holding me together and that I must most cling to; and Tony becomes the person whom I get to appreciate more and more. Beyond that there’s really nothing but work, & pornography, silliness of all sorts.’

Muriel observed this confusion sympathetically and without creating a scene. She was a psychiatrist trained to observe, not to intervene. She loved Stephen and she did not wish to challenge his ‘ambivalence’, as he called his obsession with Tony whenever he discussed it with her.

As far as Stephen was concerned, Tony’s reaction was more important than Muriel’s. ‘Tony has been terribly upset about this, although he was extremely generous about it, and never felt in the least resentful. In fact, he was very fond of her.’ Tony was anxious that Stephen might want to get rid of him; and Stephen understood. He reassured Tony. ‘Even if I married, it wouldn’t form a separation, because we would want to live together for our whole lives.’

His relationship with Muriel faded because chance and politics prevented them from spending more time together. Then Stephen suddenly decided that he could not go on living with Tony. ‘We had come up against the difficulty which confronts two men who endeavour to set up house together. Because they are of the same sex, they arrive at a point where they know everything about each other and it therefore seems impossible for the relationship to develop beyond this.’

Two men living together formed ‘a substitute relationship in which each of the two expects the other to be something other than they are, because each of them is a substitute for something else’. Instead, a man and a woman living together could map out an area of reciprocal incomprehension that would allow their relationship to grow.

It’s surely odd to suggest that heterosexual relationships work because they are based on mutual incomprehension, but he never went back on this view. It was even more odd that my mother, years later, defended this idea. I remember discussing it with her long after Dad’s death. She told me: If you are two people of the same sex, each will know how the other is feeling just by the shape of your companion’s shoulders as he (or she) gets out of bed in the morning. And, consequently, how the whole day will go. Whereas if two people of the opposite sex live together, there will be things that you’ll never understand about each other, however close you become.

Mum told me this without seeing the absurdity of the idea. I wondered if Dad hadn’t been trying in his mild way to explain away his preference for men with a joke. I also wondered how she’d have felt if she’d ever interpreted his idea that heterosexual love is based on incomprehension as a rejection of herself; but as far as I know, this never happened.

In World within World, he suggests that the attraction of working-class men was so unusual, it constitutes a gender of its own. ‘The differences of class and interest between [Tony] and me certainly did provide some element of mystery, which corresponded almost to a difference of sex.’ There are men, and there are women – and there are working-class men who are somehow in between?

I hear the ghostly voice of Tony murmuring in my ear, telling Dad: Steve, you’ve gone daft!

Lincoln Kirstein wrote from New York to say how upset he was that Stephen’s relationship with Tony had failed. ‘I had your companionship in my mind as a kind of standard where I thought there is practical friendship.’ He’d met Tony in London the year before. (They’d all gone to the Zoo together.) ‘Of course it was irresistible that it broke up. And I’m glad it happened as it did.’ Meaning without recrimination. ‘I’m so much in the same situation except its worse since I’ve no one like Tony.’

Earlier, Stephen had written to Kirstein: ‘As far as homosexuality goes, it is for me utterly promiscuous, irresponsible, adventurous excitement: the feeling of picking someone up in a small village and going on somewhere else next day. This is very anti-social, but there it is.’ Kirstein agreed. ‘Its an uncontrollable unpolarized attraction which swells up around any one that looks in kind of a warm way.’ The opposite, in other words, to faithful companionship. Kirstein wondered if he should give up the idea of living with anyone. ‘I hate to think I’m completely separating a very important part of my life from its front source, but that’s what seems to be happening.’

To Kirstein, casual affairs gave a sense of loss. ‘The intensity of some super-charge is there, for waste. The waste is what is detestable. Also it’s all confused with me in questions of class. I idealize the workmen and I can’t stomach the boys I knew in college. In one way its suicide or romanticism, but in another it prevents me from being promiscuous and widens the range of my sympathies.’ Kirstein had already eliminated the idea of living with a social equal. Now, living with a social inferior presented its own problems. But he told himself, at least desire for working-class boys had nurtured his sympathies regarding their predicament.

Stephen’s separation from Tony took three years and it was as painful as any ending of a relationship could be. There was no separation between their private feelings and the dark progress of Fascism in Europe, corroborating my father’s lifelong conviction that in the Thirties, in a most unusual way, private and public dramas became fused.

At the end of 1935 Stephen and Tony, together with Christopher and Heinz, sailed to Portugal where they had vague plans to start a writers’ retreat. This failed early in 1936 and Tony and Stephen left for Barcelona, a city that Stephen knew from his days there with Hellmut. They arrived just in time to see the first phase of the Spanish revolution which, towards the end of the year, was challenged by the arrival from North Africa of a Fascist army bent on destroying it. Back in England, Stephen became engrossed in attempts to drum up support for the Republic; and, between one public appearance and another, he married his first wife.

I never met Inez Pearn. I remember staring at a portrait in an exhibition labelled ‘Mrs Spender’, painted in 1937 by Bill Coldstream, who later became the head of the Slade where I studied art. I must have been fifteen or so. I did not recognize my mother. I told Dad that it was a very bad likeness and he said, ‘That’s not Natasha. That’s Inez.’ This was the only time I ever heard her mentioned.

The portrait shows a tense though intelligent young woman trying to nestle deeper into the sofa on which she’s resting. My father first met her at tea with Isaiah Berlin at All Souls one afternoon in October 1936. He’d come up to Oxford to give a speech in support of Spain. Seeing Stephen eyeing Inez intently, Isaiah joked that perhaps this was the woman he’d marry. Isaiah always blamed himself for putting the idea into Stephen’s head – and he may not have been wrong. My father, intensely self-willed, had the peculiar idea that he had no will at all. ‘I have no character or will power outside my work,’ he’d written in 1929 in his Hamburg journal. ‘In the life of action, I do everything my friends tell me to do, and have no opinions of my own. This is shameful, I know, but it is so.’

When Inez met Stephen, she was in the middle of two love affairs, one with Denis Campkin, who happened to be the son of Stephen’s dentist, and another with a young up-and-coming Oxford communist, Philip Toynbee. This was a period when Oxford was polarized between those who wanted to intervene in Spain on the side of the Republic, and the ‘hearties’ who backed the British government’s policy of neutrality. Toynbee was a glamorous figure, in fact he went on to become the one and only communist ever to be elected President of the Oxford Union. But if Philip was glamorous, Stephen was even more so. He was a famous poet, and his support for the Spanish Republic meant that he was constantly present at meetings – distracted and sometimes confused, but perhaps for that reason a useful supporter for the communist cause. A hesitant conscience was more convincing to the students than dogma.

Inez could never bring herself to end one affair before starting a new one. She was not confident in her looks, although ‘she had the kind of drive and concentration on the other sex which leads to success. Those who were attracted to her thought her very pretty, those who were not found her ordinary looking’. This in a romantic self-portrait from one of her novels. It bolstered her self-confidence if a man fell in love with her, because it reassured her that she was capable of love. She suspected that love had been drummed out of her by her dreadful upbringing. Her father had died before she was born, and she was raised by her weak mother and a manipulative aunt. She was determined not to fall back into the dismal predicament of her childhood.

Inez a few weeks after marrying Stephen.

My father saw Inez just that once at Isaiah’s, then a month later he invited her to a housewarming party at his new flat in Hammersmith, freshly decorated with the latest furnishings bought with the unexpected profits from the ‘communist’ book (as he called it) that he’d just written: Forward from Liberalism. Bentwood chairs and copper ceiling lights such as he’d seen in Hamburg in his earliest moment of freedom. There, seeing how attractive she was, he took her into a side room and kissed her. The next day he invited her to lunch at the Café Royal and proposed marriage.

She went back to Oxford in tears, and when she saw Philip Toynbee that evening, he was appalled to hear that she hadn’t said no. Though he tried to persuade her not to go through with it, he knew that in the end Stephen would win.

In the contorted weeks that followed, Philip continued to sleep with her while Stephen stayed in London. At one point, to shake off Philip, Inez had a brief fling with Freddie Ayer, a young philosophy don. It didn’t work. Freddie and Philip met and made friends. They agreed over drinks that it was important to them to give satisfaction to a woman in bed; yet in all this mayhem nobody was permitted to show jealousy towards anybody else. Jealousy infringed upon freedom; and ‘free love’ in those days was almost a political belief.

Stephen proposed to Inez on 13 November 1936, and they were married a month later in a registry office in London. ‘I’m just not capable any more of having “affairs” with people,’ he wrote to Christopher; ‘they are simply a part of a general addiction to sexual adventures.’

The marriage had a devastating effect on Tony, who’d been joking and plotting with Philip Toynbee up to the very last minute, in the taxi as they went to the ceremony together. He left to fight in Spain two days after the wedding. He’d been threatening to do this for months. Stephen had been torturing himself with thoughts that if Tony went to Spain, he, Stephen, would be responsible. Tony couldn’t make up his mind whether this interpretation was true or not. On the one hand it was good if Stephen suffered, because it would keep their relationship alive. On the other hand it took away Tony’s autonomy as a man who was in charge of his own life – as someone capable of taking a moral decision to go and fight, unlike the pusillanimous Stephen.

Less than a month after Tony left, Harry Pollitt, head of the Communist Party of Great Britain, invited Stephen to the Central Office in King Street and proposed that he travel to Spain in order to trace the whereabouts of the Komsomol, a Russian ship loaded with munitions which had mysteriously disappeared on its way to Barcelona. It was an odd thing to ask. Finding the Komsomol was a problem that either could be solved easily, by asking the Red Cross, or else was very difficult, in which case Stephen risked being shot as a spy.

In Spain, my father’s idea about how to find a missing Russian ship was to ask anyone he met in newspaper offices and in bars if they’d heard anything about it. Within a week of his arrival, three intelligence services knew about him: Republican, Fascist and British. At one point he wanted to cross the lines and ask the Fascists, but by that time his quest was well known and he was turned back at the frontier. It would have been embarrassing for General Franco if he’d had to shoot a British national.

The British authorities became interested. What was he up to? London sent back this message: ‘Stephen Spender was born on 28.2.1909 and is a person of leisure and private means. He became a passionate anti-fascist as a result of travel in Germany, and has lately come to see in communism the only effective solution of world problems. His views are set out in his two recent books, The Approach to Communism, and Forward from Liberalism and he has also produced poems of considerable power. He is in touch with members of the international left-wing group in London, but has not, so far as we know, engaged in active politics.’ The local officer in Gibraltar noted: ‘Up till now, as far as we know, his communism has not been more than theoretical. It may be necessary to keep a sharper eye on him in the future.’

He went back to London none the wiser on the subject of the Komsomol and reported his lack of findings to King Street. Harry Pollitt then persuaded him to join the Communist Party, which Stephen did, writing a dramatic article for the Daily Worker: ‘I join the Communist Party’. Then Pollitt sent him back to Spain to run a radio station.

By the time he arrived in Valencia, the radio had been suppressed.

At this point Stephen heard that Tony had attempted to desert from the International Brigade and was under arrest. He spent the following weeks attempting to save Tony and bring him safely back home. This enormous effort brought him into conflict with the communist commissars whose job it was to keep discipline among the volunteers. Sadistically, they restricted the occasions when they could see each other; though they didn’t stop Tony from writing to Stephen – these letters being read by their censor. ‘Oh my darling, it all seems so terribly unfair,’ wrote Tony after one of these meetings. ‘I don’t think I could bear even to see you again only for a short while. Such short-lived happiness only leaves me more torn and miserable than ever. But do come if you can.’

Stephen went behind the backs of the commissars. He contacted the British acting Consul in Valencia, who was sympathetic, and the Spanish Minister of Munitions, Alvarez del Vayo. Stephen’s reputation as a poet was a valuable commodity to the Spanish Republic, more valuable than the intransigence of the commissars, who naturally became furious when they realized they’d been bypassed.

Stephen could see Pollitt’s point of view, which was that deserters from the front couldn’t be treated leniently. But he also felt that, if he could save this one man from a fate he did not deserve, he shouldn’t give up. ‘What with your family and your friends, you have been more trouble to me than the whole British Battalion put together,’ Pollitt told Tony on one of his visits to Spain. He promised Tony he’d be on his way home within a week.

Exasperated by endless meetings with Stephen to discuss the Tony problem, Pollitt cut through one conversation by asking Stephen a simple question: ‘Is there any sex in this?’ It was a key moment in my father’s life. He did not tell lies. As far as he was concerned, he had no choice but to answer truthfully. So he said, ‘Yes.’

The Spanish Civil War retained a personal element that vanished in the subsequent much larger European war. Even so, a confrontation discussing the sexual relationship of a deserter and his lover seems to me one of the strangest of all war stories.

Stephen last visited Spain to attend an international writers’ conference that took place under the threat of imminent defeat. Groups of authors were driven in grand cars from one hotel to another. Speeches were made and delicious meals eaten. Stephen decided to challenge this opacity and ask the delegates for information about ‘certain methods which were used in Russia and in Spain and were they prepared to say that they accepted full responsibility for these because they were inevitable and necessary?’ Was it true that summary executions of members of the anarchist brigades by the communists were taking place behind the scenes? ‘I wanted to know what was going on, and why, and who was responsible for it.’ There was no answer. Instead, the question was attacked and Comrade Spender criticized for believing ‘bourgeois propaganda spread by fascist agents’.

The writer Sylvia Townsend Warner, a member of the committee in charge of the English delegation, told him firmly, ‘what is so nice is that we didn’t see or hear of a single act of violence on the Republican side’. She saw Stephen as ‘an irritating idealist, always hatching a wounded feeling’. She wanted him expelled from the Party immediately. ‘She was concerned, she said, lest they were giving the wrong advice to their young writers: this was an issue of far greater importance than the fate of Spender.’ The Hyndman case would provide all the necessary justification.

As soon as he got back to England, Stephen wrote a letter of protest to Harry Pollitt. He was being victimized in a smear campaign. ‘When I was in Spain I discovered that the other members of the English delegation were occupied in acting as amateur detectives, apparently under the impression that it was their duty to “send a report to King Street”. If any such report has been made, I think I should be allowed to answer it.’

Had Harry Pollitt betrayed him? ‘I would like to remind you that on an important occasion when you asked me a leading question, I answered it truthfully. I am prepared to answer any other questions. But it is very painful to me that my confidential answer to your confidential question has been used to slander and prejudice people against me.’ He was worried that his ‘yes’ on that fateful occasion might enter the public domain.

A few days later, Stephen invited Philip Toynbee to lunch at his flat in Hammersmith. Philip had visited Spain and the inevitable fall of the Republic was on everyone’s mind. He’d also been seeing Inez in Stephen’s absence, resisting her offer to leave Stephen and come back to him. In an aside, she spoke very bitterly about her husband. ‘Stephen, she said, was utterly thoughtless and egocentric, unimaginative, going through the motions of generosity, but hopelessly ungenerous in his heart.’

The conversation at lunch was entirely about Tony: his stomach ulcers, the censorious moralism of the British commissars and the authoritarian role of Harry Pollitt. Stephen was panicking at the thought that he’d told Pollitt the truth. His ‘Yes’ meant that he’d descended to the level of sexual predator, with Tony as his innocent working-class victim. His own view of himself as an upright and honest man was under siege, for his position was dishonourable in the eyes of the CP.

Whenever my father thought that his integrity was under threat, he’d lash out in self-defence. He’d learned this at school, I think. He makes a comment somewhere in his journals: you can accept any kind of teasing or bullying at school, but there comes a point where you have to lash out, or sink.

After lunch, Inez and Philip were left alone. Inez, who’d been silent during the meal, told Philip wearily, ‘It’s like this every day!’ When Stephen came back, he went on talking about Spain. ‘Stephen very anti-Russian,’ wrote Philip, who still followed the Party line, ‘grotesquely & ignorantly.’ Inez whispered to Philip in the background: We can now look forward to an article entitled, ‘I leave the Communist Party’.

My father abandoned communism after the Spanish experience, not just for political reasons – though there were plenty of those – but because the puritanism of the communists regarding personal behaviour was so great it constituted a political threat of its own. The communists were as repressed as the Victorians, Stephen wrote to William Plomer. It was inescapable. ‘I believe in communism & wd therefore like to be a good communist, which means being a very normal & bourgeois person indeed. But now I know I can’t manage to fit into this kind of life any more than the life which my parents wd have liked for me.’

If it meant leaving the Communist Party because of Tony, then so be it.

It is much best to accept the fact that I am not only a cad but that in the last resort I am prepared to act unscrupulously. If one accepts this, then there is quite a good working basis on which to adjust things as I don’t want to make people unnecessarily unhappy although I have done so without meaning to & would now even do so knowingly if I thought it was necessary to break away from the new bourgeois trap in which I am caught.

It’s a confused sentence. He’s sorry about hurting people’s feelings, he’s a ‘cad’, but at the same time he’d fight ‘unscrupulously’ against the ‘bourgeois trap’ of communism. Yet all the while he still believes in communism as an idea.