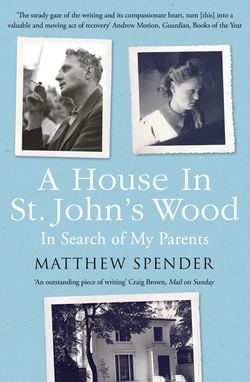

Читать книгу A House in St John’s Wood: In Search of My Parents - Matthew Spender, Matthew Spender - Страница 12

5 MUTUAL RENAISSANCE

ОглавлениеMY PARENTS MET in August 1940, a fortnight before the beginning of the Blitz. Tony invited a young pianist from the Royal College of Music to lunch at Horizon, just around the corner from where they happened to be: my mother, Natasha Litvin, aged twenty-one. She thought ‘Horizon’ was the name of a pub, not the magazine where my father worked. She wasn’t sure if she’d come. ‘Oh come on ducky, you’ll enjoy it,’ said Tony. And so she went.

Mum was living with her mother off Primrose Hill at the time, in a flat with one sitting room, one bedroom, and a tiny room under the eaves with a stove and a sink. She once told me that when she was a child practising on the upright piano perched on the landing, if she fell into a daydream, the door above her head would open and Granny would lean out and whack her head with a saucepan to get her going again. At this point however her childhood was over. She was a scholarship student with a promising career, and she’d been invited to practise on the grand piano of Ian and Lys Lubbock, who lived near Coram Square.

Every morning she walked down past the Zoo and along Prince Albert Road to the Lubbocks. Signs of war were everywhere. On Primrose Hill, an ancient wood had been cut down to make room for anti-aircraft guns. The animals of the London Zoo were being evacuated to Whipsnade in Bedfordshire, protesting, in large canvas-covered trucks. The bombing was expected to start at any moment.

The first thing she noticed as she walked into the Horizon office – my father’s flat – was a long table against the wall, piled high with books and manuscripts. The larger room overlooking the square contained a wing chair covered with pink silk, a big horn gramophone with a stack of records running along the floor and a long trestle table set for lunch. Awed by these surroundings, Natasha knelt and flipped through Stephen’s records: Schnabel’s ‘Beethoven Society’ recordings of the sonatas, the Busch recordings of the Haydn quartets and Fritz Busch conducting Mozart operas at Glyndebourne. Her taste precisely. And casually propped against the wall near the records, a little Picasso watercolour.

She was briefly introduced to Stephen, but before she could ask him about his taste in music, they sat down to lunch. A crowd of about ten people in the small flat. Cyril Connolly, Horizon’s main editor, sat at the head of the table. Natasha was down near the novelist Rose Macaulay, whom she remembered as having kept her crumpled velvet hat on at table, complete with veil.

Looking at Stephen surreptitiously from a distance, Natasha realized this wasn’t the first time she’d seen him. Three years earlier, in October 1937, she’d joined a group of music students at the Kingsway Hall in London during a rally on behalf of the Spanish Republic. By that time the Spanish cause was as good as lost, but this did not make Stephen Spender less of a glamorous figure. He described the young English poets who had fought and died for Spain: John Cornford, for example, and Julian Bell, the nephew of Virginia Woolf. (‘Spender praised the representatives of culture who had lost their lives whilst fighting with the Spanish Government Forces,’ wrote a listener from MI5.) Natasha admired Stephen’s speech because, unlike the others on the platform, what he said was free from the usual bombast.

After lunch the guests mysteriously disappeared, leaving Stephen with the washing up. Natasha helped – and that was that. As a child I often imagined this scene: the guests leaving with their fingers to their lips like actors miming silence in a film. He’d been depressed all winter and his friends were longing for him to start a new life.

Years later, she described how she looked when Stephen first saw her. ‘He probably thought me rather demure, even old fashioned, with my hair parted in the middle and the two long plaits wound over the head in Victorian style.’ This is typical of the way my mother saw herself: shy, retiring, perhaps at some level even anti-social.

After they’d tidied up, they walked around Mecklenburg Square, and then out to supper together, staying on until the restaurant closed, darkness fell and Natasha had to go home in a taxi. During their walk Stephen mentioned the death of a friend, and he stopped and shut his eyes in an unconscious expression of pain. This was what attracted her: his willingness to reveal emotions. Not many Englishmen she knew did that.

They were both tall, so there was no problem about keeping up with each other when they walked in Regent’s Park next day. And the next. And the next. Less than a week later, in another taxi with the Lubbocks going from a cocktail party to their house to have dinner, a tipsy Ian leaned forward and told Stephen that he should ‘take on’ his wife Lys, not Natasha. Which suggested to Natasha that in the eyes of the world, she and Stephen had already ‘taken on’ each other.

My mother writes this regarding her first impressions: ‘The sudden luminosity of spirit which possessed me from that first day, I remember as a kind of mutual renaissance shared with Stephen, in whom one could sense this tentative turning towards the light, whilst I also was moving away from a restless year I had spent in Hampshire as paying guest of Susan Lushington, where music had been the only solace from the troubled impermanence I had known since 1939 in both outer and inner life.’ It’s a long sentence. When it came to revealing her emotions, my mother wanted to cram everything in and move on.

With several other Royal College students she’d been evacuated to Ockham Hall, where Susan Lushington, a keen amateur musician, had offered them hospitality. ‘Despite successful achievements at the College and beyond, in recovering from an illness I had been troubled about the value and direction of my daily devotion to music.’ She was certainly something of a success. In March 1940, she’d performed Beethoven’s 4th piano concerto with the Royal College Orchestra under Malcolm Sargent. Not the easiest piece in the world. But illness? I know nothing about this, but my mother once told me that she’d had a stomach ulcer at the age of twelve, which suggests stress.

Her fellow students were marrying or going off to the war, or both in quick succession. What was to become of her? She didn’t want to live with a musician and she hardly knew anyone else. A musician ‘would be confining, compounding of stress, and prone to shop-talk. Too narrowing.’ She was not interested in politics. ‘Public life, its battles, crowds and compromises were not for me.’ She could see herself doing good in a quiet way, at an individual level. ‘I was a kind of agnostic Christian, totally unconcerned with dogma, but fond of and admiring those selfless lives, whether historical or personally known to me, which combined a sense of the sacred with understanding, love and tolerance.’

In the few diaries my mother left she insists that an introspective life would have suited her best. The life she chose with Stephen was the opposite of that, but she wasn’t incapable of presenting a brave face to the world. Quite the contrary. She was also a musician, so she knew how to perform.

My mother was the illegitimate daughter of Rachel Litvin, an actor of Jewish ancestry born in Estonia, who’d come to England with her family as a child. Her father was Edwin Evans, a well-known music critic and champion of contemporary French composers. Unfortunately, my grandfather was married when Ray became pregnant, and although he offered to obtain a divorce, my grandmother refused.

In these dire circumstances, Ray was helped via her friendship with Betty Potter, a fellow actor, whose powerful sisters took over my mother’s birth and foster care. Bardie, one of Betty’s sisters, even offered to adopt her, but Ray refused. Margaret Booth, married to the son of the shipping magnate Charles Booth, became Natasha’s ‘Aunt Margie’. In fact all the sisters became Natasha’s elective ‘aunts’.

When Natasha was a few months old, the ‘aunts’ found a foster-mother for her. Unencumbered, my grandmother did her best to continue her career. ‘I walked with Miss Litvinne, mother of an illegitimate child, down Longacre, & found her like an articulate terrier – eyes wide apart; greased to life; nimble; sure footed, without a depth anywhere in her brain. They go to the Cabaret; all night dances; John Goss sings. She was communicative, even admiring I think. Anyhow, I like Bohemians.’ Thus my grandmother depicted by Virginia Woolf, of the sharp eye and sharper tongue, in the year 1924, when my mother was three. The following year she saw Ray acting the part of an orphan in a play. She was not impressed. ‘Poor Ray Litvin’s miserable big mouth & little body.’

Throughout my mother’s childhood, the Booth family at their grand house on Campden Hill, or at their even larger property at Funtington in Sussex, took care of my mother and encouraged her musical gifts. Funtington was full of the Booth children, although they were slightly older than Natasha. There are photographs. She is with them. They are in a magnificent tree-house in a chestnut tree. ‘The joy was to be allowed to join them there among the dark foliage, pulling the ladder up after us, impregnable in our leafy hideaway.’ At Funtington there was a bedroom known as ‘Natasha’s room’, which means that my mother must have spent most of her holidays there.

The Booths were obsessed by music. Everyone played an instrument and they could perform complex chamber pieces without the help of musicians from outside the family. Aunt Margie looked down the table one Sunday lunch and said, ‘Oh good. This afternoon we can play the Trout.’ This, to my mother, was incredible luxury – and she was right! Who today can play Schubert’s Trout Quintet, and the performers are all related? Beyond their music, the Booths enjoyed what my mother calls ‘a democratic radical classlessness going back to Bright and Bentham’. I’m not sure whether ‘classlessness’ is the right word, but the Booths stood at the head of a strong tradition of English socialism. And they were rich.

Little Natasha grew up in three worlds: that of her foster-mother Mrs Busby, that of the powerful self-appointed aunts, and that of everyday life at school. She learned to speak in three different accents and she was proud of the fact that she could alter these voices instantaneously. ‘As I grew, so did my ability for chameleon changes of manner to suit the ambience in which I might find myself. Yet at the centre of this changing stream of consciousness and easy, reliable adaptation to frequent changes of scene, there was a certain unequivocal sense of unity, an intact sense of self.’

Until she was twelve years old, Mum hadn’t even known that she had a father. By that time she was in secondary school and doing well. She loved her foster-mother and the Booth family stood in the background to give her a sense of security. Then suddenly my grandmother told her that she’d be leaving Mrs Busby and coming back to London to live with her; and that the following day she’d have to visit the person Ray had never married and ask him for money.

The next day Mum boarded the 74 bus from Primrose Hill to Earls Court to meet the unknown man who happened to be her father. A housekeeper opened the door and she found herself in front of a large bearded gentleman in a pair of carpet slippers. He neither hugged her nor shook her hand, but he was a musician, so he could talk about that. He showed her his scores stacked from floor to ceiling, talked about French composers she’d never heard of and took her to the piano and played a bright little sonata by Scarlatti.

‘His speaking voice was rather flat, the accent indeterminate, his laughter rather ponderous, and much of his musical talk was above my head. Somehow the occasion was lifeless, for although his kindness was apparent, dutiful, impersonal, it was difficult to feel anything at all.’ Then, sitting side by side at the piano, he improvised a theme and invited her to join in. Her earliest love for the piano had come from improvising for hours on end, so she added a second subject. And that was the closest she remembered ever getting to her father. An old man and a young girl at a keyboard, tapping at the notes.

My mother aged fifteen, photographed at the Booth country house near Funtington.

Edwin Evans had no intention of marrying Ray Litvin, or even of seeing her again. He’d give her an allowance of some kind but, as he told his daughter when they said goodbye, he’d arrange everything through a solicitor. There was no need for her to come again.

Years later, Mum happened to perform in a concert conducted by Eugene Goossens. He looked at her speculatively across a dining-room table while he ran through a mental list of Edwin Evans’ mistresses. Finally: ‘Oh, now I remember! You must be the daughter of the Russian woman!’ One of the many was the implication.

My grandfather died ten days before I was born, so I never knew him.

Mum told me years later that she felt very little when her father died, and she’d had to piece together everything she knew about him after his death by talking to composers who felt indebted to him. Francis Poulenc, for instance, whom she met in Paris in the late Forties. He told her many stories about Evans, but she did not write them down, and when I asked her about them, she’d forgotten. Igor Stravinsky told her that Evans was the critic who in 1913 had insisted on the first performance of The Rite of Spring in London, for which he was very grateful. He gave Mum a copy of a photo from his family album showing her father standing on a veranda in the South of France with Diaghilev and Picasso.

Stravinsky told her that Evans had been with him in a taxi in Paris when he’d found the solution to the last pages of Les Noces. He’d been working at it for months and he couldn’t think of a way of ending it – four soloists, four pianos and a choir, a devastating piece. Then he and Evans happened to be travelling past the cathedral of Notre-Dame one Sunday morning when all the bells started ringing. Stravinsky stopped the cab and wrote down the deafening notes as dictation.

Among the photographs that my sister Lizzie and I inherited is a yellowed newspaper clipping showing our mother with Stravinsky in the streets of Salzburg in the late Sixties. Stravinsky walks with difficulty and she’s helping him. It’s a moving image, but it took me a long time to see why. Stravinsky is cheerfully tottering, and that’s understandable, because he’s ancient. Then I saw it. Mum’s body-language was unfamiliar. It was the affectionate willowy bending of a daughter towards a father.

On Saturday 7 September 1940, Natasha had lunch with a group of young architects in a flat overlooking the Thames somewhere to the east of the Houses of Parliament. They came out and walked along the Embankment. The air-raid siren started. They checked the nearest bomb shelter but it seemed dank and dirty. ‘Returning to lean on the parapet of the river, we gazed around us, when we suddenly caught sight in the east of a vast number of planes flying upstream from the estuary, and glinting in the sky like a shoal of silvery fish.’ They stared upwards without moving. In spite of warnings in the newspapers that the bombings were about to start, they had no fear. ‘One could not readily imagine at first that this was, as anticipated, the start of lethal enemy action on London, for in our leisured mood, the beauty of the day and of the gleaming, steadily advancing planes was almost hypnotic.’

Stephen at that time was living with his younger brother in the country. He rushed up to London to take charge. He decided she should move out. He took her to Oxford and called on Nevill Coghill, Auden’s former tutor. Coghill was an amateur musician and Natasha had already given a concert in Oxford, so he knew how she fitted in. Word went round. Within a few days Natasha was installed. The old Bechstein her father had given her was moved to a room above the Church of St Mary, opposite the Radcliffe Camera. It was a beautiful room to practise in, though the choir occasionally took it over for their own rehearsals.

In the early days of their courtship Stephen and Natasha did not live together, because my father did not want her to become roped into the divorce proceedings with Inez. They met once a week in London. Natasha would hitch a ride at the Headington roundabout outside Oxford. That roundabout became a symbol of the war: officers and soldiers and mechanics and students and professors – you never knew who’d be standing next to you or who’d offer you a lift. For twenty years after the war it was remembered with nostalgia as a moment when class faded, everyone was in it together, no place to sleep was a good place because all places could be bombed, so travel light.

The Blitz, at least in this early phase, was met with bravado. Once, under a bombardment, caught among a group of partygoers who refused to troop off to the shelter, Natasha was told, ‘play something lyrical’. So she played some Chopin waltzes – ‘Chopin, for heaven’s sake, which I almost never played!’ A couple of distinguished guests lurked under the piano, giggling and passing a bottle of champagne to each another, wondering if a grand piano would give them any protection if a bomb came through the roof.

Over the winter of 1940–1, Stephen and Natasha stayed for a fortnight with friends in an eighteenth-century house south-east from London, near Romney Marsh. Wooden poles had been raised against the German gliders that would come over in the expected invasion. The winter had turned cold and a heavy snowfall smothered the countryside. Everyone in the neighbourhood had relatives in the armed forces, but the snow had lightened the mood, for the enemy bombers were grounded. The house had a warm kitchen and a warm workroom and they ran from one to the other through freezing corridors. The whiteness was reflected on the ceilings; and outside, the shadows of low clouds skittered over undulating snow.

This was the first time that Stephen and Natasha had spent more than a day together. Stephen worked in the attic in his overcoat while Natasha studied the Schubert B flat posthumous sonata, ‘with its devout quality reflecting an atmosphere of laudate adoremus, in tune with the advent of Christmas’. After a few days, their hosts disappeared and they were left alone. The ‘Wittersham Interlude’, as my mother calls it in her memoir where it occupies a whole chapter, was an important moment in my parents’ lives. Each laid out the past for the benefit of the other.

Stephen kept thinking of the tattered members of the International Brigade who’d fought in Spain, friendless and badly equipped. He compared them with the British forces in North Africa, well trained, well armed and backed this time by an entire nation. This war was for England; but it was also a moral cause. ‘Stephen’s conviction [was] that all repressive despotism had to be opposed by decency and insisting on truth. He had seemed so mild when we first met, that coming to know his strong-minded refusal to acquiesce in any political coercion and lies was to recognise a centre which was steady, even steely, in his peaceable nature.’

My mother practising the Schubert B-Flat Sonata in the early years of the war.

They discovered that they both had feelings of guilt about the First World War. As she puts it in her memoir: ‘So many of our generation had felt guilty for having missed the first war and for our existence as burdensome, as somehow responsible for the sadness and privations of our parents.’ Natasha’s guilt perhaps had more to do with the fact that she was illegitimate, but she resisted this thought.

Although at the age of twenty-one on the Wittersham holiday I had long since found a robust, even amused acceptance, of such relics of childhood, there remained a lifelong, lingering feeling of apology towards my mother for her lonely years of adversity. I had never entertained untoward feelings about illegitimacy, for it was clear that there was no reason for me to feel responsible for that, despite my sympathy for her moments of embarrassment. But I continued to feel a sorrowful indebtedness for the struggle she had bravely faced to support us both.

Stephen told her: ‘As very young children they had been appalled to feel their noisy play to be responsible for their mother’s bouts of illness, when she appeared looking over the banisters and declaiming, as Stephen said like Medea, “Now I know the sorrow of having borne children.” After her early death at the age of 42 they felt partly responsible for their father’s unhappiness, a burden they could not alleviate, and perhaps that they even had had a share in its origins.’ Stephen felt he’d rejected his father, towards whom he’d shown no sympathy after Violet died; but this took time to emerge. Years later, after I was born, Stephen told Natasha: ‘Our father must have been desolate after the death of our mother, and I don’t believe we gave him any comfort.’

At Wittersham, Stephen spoke openly about Tony and Inez. My mother summed up what he said in a simplification which has a certain truth, though I don’t believe it covers everything. He felt they’d failed, because he’d spent too much time working. ‘His devotion to his vocation in poetry was an unforgivable distraction – a sort of infidelity – for he was a transparently monogamous temperament.’ My mother cannot have found it easy to accept Tony and Inez, standing invisibly offstage throughout the Wittersham Interlude. But ‘monogamy’ was an admirable virtue. So was work.

He told her about his early years in Berlin with Christopher Isherwood and with his younger brother, Humphrey. She was prepared to forgive him. ‘He had lived his life in phases, and the earliest one of juvenile wild oats shared with Humphrey and with Christopher had in a few years been discarded like an animal shedding its skin. His monogamous devotion to Tony had foundered for reasons I well understood, and his latest disaster with Inez was to a union which had never been properly joined.’

Natasha told Stephen that his unsuccessful relationships with Tony and Inez were not his fault. ‘His assuming total responsibility for these failures was a far from wise interpretation, for Inez had been in a whirl of indecision, even on her wedding day, when she was still at Oxford.’ So, exit Inez. As for Tony: ‘The pattern of Tony’s restlessness had been lifelong.’

She told him: ‘From now on there is no question of blame. There is only us.’

‘I look back on that brief holiday as a time of exceptional élan in the feeling that we had dropped our childhood like unwanted luggage.’ They loved each other. Their guilts could be discarded. ‘The resolve I shared with Stephen to banish both self-blame and, in the future, any projecting of it upon each other, and to replace it with serene understanding of its origins, was to enhance the feelings of release from the past and rejoicing in the present which pervaded those happy snowbound days.’ He’d told her everything about himself. He was turning over a new leaf – or so she thought. But he might also have been giving her a warning: Don’t expect from me more than I can give.

They were married at St Pancras registry office on 9 April 1941.

‘As we made the responses, it was, as we later described it to each other, as if we were alone in some high place – a water-shed where our pasts flowed away into one ocean, and our future together was a stream flowing away to another great sea, as we stood there at its source.’ Together, they would descend the other side of this mountain, leaving the past behind. ‘Meeting in forgiveness and the miracle of marriage, I realised that it had been this acceptance of whole histories, reaching back into previous generations, which had been distilled into that one present moment, (almost a knife-edge), of the vow.’

Stephen wrote to Julian Huxley: ‘being married to Natasha will be quite different from just living with her, as she is really a very remarkable person’. Her character was in its way deeply religious. ‘“Being married” means something to her. This has a revolutionary effect on me, because nothing alters me so much as someone expecting something real from me, and the desire not to disappoint her in any way.’ This was part of his idea that he had no will of his own. He would try to live up to her hopes, because they were stronger than his.

My parents soon after their wedding.

For their honeymoon they went to Cornwall. There, he showed her the many versions of a poem on which he was working. She had no idea that it required so many revisions and restarts, but when he explained to her the idea of fidelity to an event, it related to what she was trying to do with her music. ‘For the poet or the composer there is fidelity to some original subjective experience, which is private and ultimately beyond the interpreter, however inspiring a reading there may be.’

She thought that Stephen’s creativity provided her with limitless support. ‘This rich vitality struck me like the liberation of entering another country, another climate, for apart from the Funtington circle, my not unlively musical world had been much narrower in focus.’ His world renewed her optimism. ‘Overtaken by this sudden upsurge in vitality and sensibility, music was once more intoxicating, the capacity to realise the beauty of phrasing that one intended or imagined seemed limitless … For me, the vast repertoire of masterpieces for the piano waiting to be mastered was no longer a daunting proposition, and one could set about wholeheartedly learning each single sonata.’

Walking in the countryside, there would be occasions when Stephen would become distracted. My mother read these as moments when he’d entered his interior world and she should not cross that boundary. ‘We would be chatting, in the way of friends or lovers, of an acquaintance or a landscape and yet – at a certain moment one could feel his need of silence and guess that some analogy with a dramatic or poetic theme had seized him, and he wished to chase after it in peace.’