Читать книгу A House in St John’s Wood: In Search of My Parents - Matthew Spender, Matthew Spender - Страница 15

8 AMERICA IS NOT A CAUSE

ОглавлениеMY EARLIEST MEMORY as a child is of rolling down the lawn in front of the house in Scarsdale where we lived when my father taught at Sarah Lawrence. It’s not much of a memory. I vaguely recall being plump and cheerful. My mother was with us; also an English nanny who longed to go home. The only things that interested the nanny were the sales in the department stores.

This was my father’s first visit to the United States, and it represented the beginning of a new axis in his life. America represented money, and like many English writers he came regularly to the country on visiting professorships or on lecture tours. Sarah Lawrence was a good place to start. Among others, he met Robert Lowell, who came for a visit, and Mary McCarthy, who taught there for a year while she gathered material for The Groves of Academe. I don’t know what my father thought of his pupils, but when a Picasso lithograph he’d brought with him disappeared, he complained to the President. ‘Sarah Lawrence girls don’t steal,’ was as far as that went.

During this time there occurred a famous quarrel between Lillian Hellman and Mary McCarthy. Hellman represented the unrepentant Stalinist wing of the old American Communist Party, a position which by this time McCarthy found physically repellent. She came across Hellman speaking unofficially to a group of students at a party where Stephen was present – not his own party, it seems, though later he remembered himself as being the host. Hellman didn’t notice McCarthy, who looked no older than the other students. Hellman was speaking in a patronizing way about the writer John Dos Passos. In Spain, he’d ‘sold out’. But then John had always liked his food, and there wasn’t much he wanted to eat in the restaurants of Spain in the middle of a war. And so on.

McCarthy instantly recognized this as a piece of communist character assassination. The real background was that Dos Passos had seen the communist repression of the anarchist brigades in Barcelona, and he had been appalled, and had begun to say so. Hemingway had seen the same thing but he’d kept quiet. Therefore, back in the United States, Hemingway was hailed as the up-and-coming writer and Dos Passos became the victim of a whispering campaign.

Mary McCarthy’s career in politics had much in common with that of my father. She was tougher and less romantic, but their early experiences with communists had a similar trajectory of well-meaning idealists led astray.

In My Confession, McCarthy describes the bizarre way in which, in 1936, she became an anti-communist. Until that date, she’d merely fitted communists into social categories. The literary communists, ‘doing the hatchet work on artists’ reputations’, she held in low esteem. ‘The forensic little actors who tried to harangue us in the dressing-rooms.’ The silent types, evidently in charge of something (but what?), who were admired because their reticence suggested authority. The ‘fellow-travellers’ who remained outside the party on some tiny doctrinal point to appear intelligent. Apart from that she’d enjoyed reading Trotsky’s autobiography; and that was about it.

Then came the news of Stalin’s purge of his former friends in the Moscow Trials – which she had missed, because she’d been in Reno getting a divorce. Back in New York, because of something she said at a cocktail party, she found herself on a list of supporters of a ‘Fair Trial for Trotsky’ group. Once there, she found she was outside the Party; and being outside, she felt the pressure of arcane, late-night persecution. This only made her dig in her heels. All of which, told in her ironic but precise way, is very interesting – but right at the end she adds a fascinating clincher: ‘Those of us who became anti-Communists during that year, 1936–37, have remained liberals – a thing less true of people of our generation who were converted earlier or later.’

This is especially true of my father, and it formed a special bridge between him and McCarthy. Yet liberalism in England meant something different from liberalism in the United States. There had been, after all, a Liberal Party in England, and it had survived from the 1840s until the First World War, when it was overtaken by Labour. Stephen belonged to those liberals who’d joined the Labour Party via the circuitous route of left-wing politics, but to be a ‘liberal’ in the United States meant working outside the folds of either political party. These liberals had no constituency. This suited Mary McCarthy very well. She could stand outside practically everything yet still represent an idea. Spender, by comparison, was mainstream.

On their way back to New York, Natasha and Stephen stayed with the composer Samuel Barber at Mount Kisco. Barber had written a setting for Stephen’s poem, ‘A Stopwatch and an Ordnance Map’, and he was a friend from way back.

Barber listened to my mother perform. Afterwards he told my father: she has a great deal of talent, but she’s missing a piece of technique without which her career will be very difficult. But don’t worry! There are piano schools where she can check herself in, like a car going into a garage. Six months later she’ll re-emerge with everything in the right place. It’s extremely boring, because it’s purely mechanical, but without it Natasha will always have to work by straining her will.

My mother had given up the Royal College without graduating. She thought she was being badly taught. She’d begun to study with Clifford Curzon, who in turn had studied with Artur Schnabel, the greatest Beethoven specialist of his generation. Clifford – he was my godfather, so I saw him at various times – could remember every word that Schnabel had ever said to him. But he taught interpretation, not mechanics. He could take a piece that Mum was studying and analyse a passage saying, Schnabel would have done it this way, Rudolf Serkin does it like this.

My father would sit restlessly in the background of these conversations, which went on right up to Clifford’s death. Once, Dad took me outside the house, where in the open air he positively danced with irritation. I asked what ailed him. He said: ‘Clifford lived for four years in Berlin, and he didn’t even notice the Nazis.’ To him this didn’t constitute dedication to his art. It wasn’t even absent-mindedness. It was horrifying.

Years later, Dad told me that he regretted the fact that they hadn’t fitted the piano-garage into their lives, although I can’t imagine how they could have found a space for it. The fact remained that my mother played the piano on her nerves, and her technique always lagged behind what she could comfortably do. In her time she played many difficult pieces, such as Prokofiev’s Third Piano Concerto, Stravinsky’s Capriccio, and of course the big staples like Beethoven’s Fifth Concerto, The Emperor. And she’d always leave off practising until the last minute. Midnight on the night before, she’d still be thumping that awkward passage in the last movement. I once came out on to the landing from my room above the piano room and shouted, ‘If you aren’t ready now, you never will be,’ whereupon a dreadful silence fell upon the house.

As a child I’d listen to her practising the same passage endlessly until her fingers went to the right places by themselves. Over the years it took a strange hold on me. As I lay on my bed upstairs reading a book, she’d go back and do those ten bars again and my eyes would go back and read those two sentences again. It was maddening. A book and a piece of music became intertwined into a mishmash of repetitions and stumbles. Words on the printed page acquired the emphasis of musical phrasing, a certain book would become associated with a particular composer. What I read and what I heard became one.

Stephen arrived in New York for his second trip to America early in April 1949. He discovered that many of Mary McCarthy’s friends were bitterly complaining about her account of them in her novel The Oasis, which had recently been published in Horizon. He wondered: Is New York any less parochial than London? ‘It is not surprising that people should be annoyed, but the feeling that the story somehow undermines the security of the characters described in it, is rather astonishing.’

The Cold War was a leading topic in the newspapers. It was becoming increasingly necessary to choose: Them or Us? Stephen looked down from his bedroom window at the streets of Manhattan and wondered, do we really have to become pro-American? What does this country have to offer? ‘The cars as fertile as weeds; the anxiety of all the things in the shops to be bought. The creation of standards whose only nature is an ostentatiousness, which excludes people who do not share these. The anxious suspicious over-generosity of Americans.’

My father is taking up the cause of the rest of the world against the United States. I think his experiences in UNESCO might have affected him. The idea that even this institution had to become pro-American was hard to accept.

A few days later, away in the South, Stephen noticed a newspaper report analysing a recent conference that had been held at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York. This Peace Offensive organized by the communists had been dramatically challenged by a group of liberals and ex-Trotsky intellectuals, including several of Stephen’s friends. Mary McCarthy had been present, bringing an umbrella with which to defend herself against the Stalinists. Stephen read the story incredulously. Communism, the cause of peace? Nonsense! Nevertheless communism was still a ‘cause’, even if it entailed, in every country where it gained power, the loss of liberty for all except a few leaders at the top. ‘America is not a “cause” in the same way. It is just America, with the American way of life and a rooted opposition to un-American ways, and tremendous waste, and a radio and a press and a movie industry, not to mention political parties, which advertise a commercialisation which is an insult to every race and class of people not directly involved in American ideas and interests.’

The fact that Americans insisted that their culture was superior to all others was agonizing to those non-Americans who had to chose between the USA and communism. ‘America judges others by her values, her interests, which prevent her from either understanding or being understood.’ The United States couldn’t grasp that its culture might be unattractive to other nations. ‘Not to see that the Voice of this America can never speak to the world – in fact, that it is only by learning the voice of the world of striving peoples that America can ever speak to the world, is a fatality which rots even America itself.’

This isn’t anti-Americanism. It’s exasperation with the choice of ‘Them or Us’, and a plea on behalf of many cultures that would prefer to choose neither. But to choose neither was not an option; and if the choice had to be made, of course it would have to be in favour of the United States.

Stephen was in the process of completing two important texts. The first was World within World, which he finished on a ranch in Taos, New Mexico, where D. H. Lawrence once lived. The second was his essay for The God That Failed, a compendium of memories written by key participants in the events of the Thirties, once communists, now repentant, some bitterly so. It was an influential book, made more powerful by the fact that most of its authors had not taken up the cause of the United States after they’d lost faith in communism. Indeed, my father’s contribution includes this: ‘Capitalism as we see it today in America, the greatest capitalist country, seems to offer no alternative to war, exploitation and the destruction of the world’s resources.’ If only communism worked, he wrote, it might provide an alternative to ‘a mass of automatic economic contradictions’. My father’s ‘ambivalence’ meant that he faithfully supported the United States while feeling ineradicable doubts about what that country stood for.

My mother and I weren’t with him on this trip. We spent the summer of 1949 in Portofino, on the Ligurian coast of Italy. I was four years old and I remember my feelings at the time. I can even remember my father not being there, as a kind of latency, the state of expecting him to turn up, shared between Mum and me.

There’s a photo of me aged four, fishing in the bay. My hat is large and floppy. My swimsuit is baggy. I remember the look of the water. Even when the day was calm and there was no wind the sea was never still. It lay a few feet below the edge of the port in glowing lenses beneath which tendrils endlessly traced the letter ess. At the beach, a sea urchin abandoned in my knee five long legs waving at the different points of the compass, patiently blundering through each other without tangling. They thought they were still in their carapace and were walking away from me – but what clever legs to do that by themselves.

I remember a race back from the beach, round the promontory and into the bay. I’ve done my best to raise it to the level of a trauma, but my life on the whole has been free of anything traumatic, so it remains just an instance of my mother behaving competitively. She had a strong competitive streak: the pursuit not of the thing itself but of the victory that winning represented.

The other participant was Alison Hooper, like Mum aged under thirty, both in cast-iron swimsuits made of some shiny material. There we were among the towels and trowels of the beach on the promontory, and Mum suddenly leaped up saying ‘Race you home.’ Whereupon Alison too sprang up, grabbed her towel and basket and started up the steps cut into the rock, of which there were rumoured to be a thousand. She took them two at a time and her calves flicked sideways as she ran.

Mum grabbed me, dropped me in the front of the rubber dinghy and started paddling. She shone with the gleeful sheen of early motherhood. Beautiful, with a child and a husband and a career, she was in the stage when the young mother says, Life, throw me a problem! There’s nothing I can’t solve!

As we set off in the rubber dinghy, our world withdrew to just her and me, the surroundings nothing but a pretty backdrop to our shared ambition, which was to paddle around the cliff and reach the edge of the quay first. So we paddled, she behind me steering and myself in front doing the best I could, with a little spade, not scooping the water but trying to hit it, except this element gave no resistance but took my hand in a brief flurry of bubbles.

Evidently we weren’t going fast enough, for at a certain moment, round the edge of the rocks and with Portofino in sight, she said, ‘Come on! You’ve got to paddle harder! There’s a shark behind us!’

Immediately the friendly element of water and bubbles became dangerous. Why did I have to put my hand in there if a shark was waiting to grab it? The shark was behind us, and between me and it there was Mum, but she wasn’t putting her hand into the sea and besides, she was armed. She could ward it off.

Now I couldn’t paddle but only stab the water as if the shark was already there, under the bobbing rubber which obviously provided no defence except at least he couldn’t smell us, but if my fist and spade flashed in and out fast enough, maybe he’d be discouraged and leave us alone. And now there were sharks all around us. I could see them under ends of the boats moored in the bay where the water was less choppy, backlit by rays that diffused into spangles of sunlight all around them. I knew these were the rudders of the boats we were passing because they were symmetrically poised and motionless under every boat, harder than any fish and more purposefully angled. But they were rudders and sharks simultaneously, for my mother was in a state of anticipated triumph and paddling furiously and I was doing my best. ‘Come on! Just a bit more!’ And we won. We were on to the hard lip of the bay of Portofino just as Alison ran up, my mother waving a towel in the air and skipping to prove we’d done it.

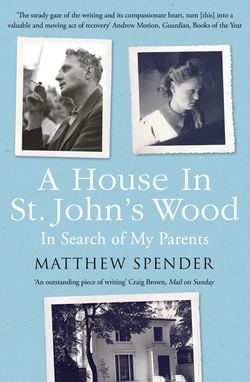

My mother in north Italy in about 1949.