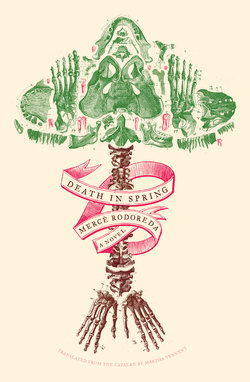

Читать книгу Death in Spring - Mercè Rodoreda - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIV

I decided to stroll through the soft grass, up the incline; at the end of the slope the tree nursery appeared from behind some shrubs. The seedlings had tender trunks and no leaves; but after they were transplanted in the forest and grew tall, they would all carry death inside them. I walked among them, and they looked like objects you see only when you’re asleep. I stopped at the entrance to the forest, at the divide between sun and shadow. I had seen the cloud of butterflies earlier. The trees in the forest were very tall, full of leaves—five-point leaves—and, just as the blacksmith had often told me, a plaque and a ring were attached to the foot of each tree. There were thousands of butterflies, all white. They fluttered about anxiously; many of them looked like half-opened flowers, the white slightly streaked with green. The leaves stirred and a splash of sun jumped from one to another; in between you could see speckles of blue. The ground was carpeted with old, dry leaves, and a rotten odor rose from beneath them. I picked up a leaf that was only a web of veins, like the wood and beams of a house, with nothing binding them together. I lay down under a tree and watched the cloud of butterflies bubble among the leaves. I looked at them through the web of leaf veins until I was tired, and as soon as I let it fall, I heard footsteps.

I jumped up and hid behind a shrub. The steps came closer. The shrub had a yellow, half-unsheathed flower and five leaves that gave off a prismatic sheen. The bee was sheltering there, dusting off its legs. I was sure it was the bee that had crossed the river and followed me from the village.

The steps stopped. Everything was quiet. As I strained to listen, I thought I could hear someone breathing. I felt a weight in the middle of my chest from listening: the same uneasy feeling I had when they locked me in the cupboard for hours, and the village was deserted, and I would wait. That was how I felt now. Nothing had changed: the leaves were the same, and the trees and butterflies, and the sense that Time inside the shadow was dead. But everything had changed.

I heard the steps again, closer now, and saw a bright flash under the leaves. The man who was approaching carried an axe on his shoulder and a pitchfork in his hand. He was naked from the waist up, his forehead smashed. His face had been disfigured by the rushing river, and he was unable to shut his eyes because the skin on his forehead had healed poorly. His red, shrunken skin was pulled tight, always leaving a slit in his eyes. He had patches of black hair on his chest; his body was sunburned.

The bee seemed to be asleep, the flower too, until a gust of air arose and the flower swayed and the bee escaped from inside, grazing my cheek; and as soon as the flower was still again, the bee flew back in. The man left his axe and pitchfork at the foot of a tree, wiped his mouth with the back of his hand, and looked round as if he were lost. I was afraid he had seen me because his eyes stopped on the shrub. But he hadn’t. He began moving from one tree to another, reading the plaques that hung from the rings. He tripped on a root and almost fell. Then he went deeper into the forest. When he was out of sight, I breathed deeply; the anxiety in my chest had kept me from breathing all that while. Flocks of clouds passed slowly by; I wished I could control them, sending them where I wanted. A cluster of very small ones came to a halt directly above the forest and stayed there a long time, giving the impression they did not want to leave. When the cluster of little clouds started to move away, the man returned. With his axe he began making a cross on a tree trunk; he had marked it with a stone, top to bottom and side to side. He worked mechanically, and after a while he dropped to his knees and began to cry. I held my breath. Still crying, he stood up, spit in his hands, and rubbed them together. The bee buzzed in and out of the flower. As the axe cut the trunk, you could see the line begin to emerge. With the first axe strokes, the butterflies went wild. Two of them flew down to the grass and stuck on one of the man’s legs as he was cutting open the tree trunk. The bee was sucking the flower. The man rested and again spit in the palms of his hands. While he was rubbing his hands together, the axe under his arm, he looked up and seemed enthralled for a moment by the flutter of butterflies. He appeared more tired when he resumed work, as if each stroke of the axe bore all the weight of life.

Much later, the man began cutting the transverse line on the cross. One blow after another. The two butterflies caught on his leg were so close together, their wings folded up so tightly, that they looked like one butterfly. The man’s back shone with sweat, his ribs too; he was very thin. I wanted to go over to him, speak to him, wanted to tell him that the blacksmith sometimes talked to me—between hammer blows, near the forge and sparks—about the forest and the dead people inside the trees.

The blacksmith had a house at the entrance to the village, a house with two wisteria vines, one on each side of the huge door, winding upward, covering the roof in a tangled mass of branches. As the sparks flew from the forge, the blacksmith told me: you too have your tree, your ring, and your plaque. I did it when you were born. When someone is born, I make their ring and plaque right away. Don’t tell anyone I told you. All of us have our ring, our plaque, and our tree. And at the entrance to the forest stand the pitchfork and the axe.