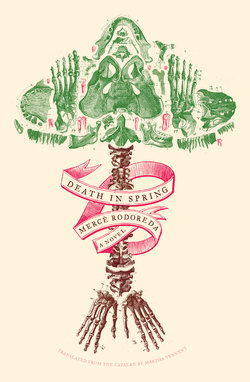

Читать книгу Death in Spring - Mercè Rodoreda - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеI

The birds always came from the direction of the cleft mountain. The ones in mourning were the first to arrive. They headed straight to the pasture where the horses grazed, cawing raucously and circling the sky all day long. On the following day they would approach the houses, raising an enormous din, soaring and diving as they hunted. The birds were black-plumed and black-billed; a white selvage circled their even blacker eyes. When they took flight, their tail and wing feathers would spread apart: you could almost count them. They would slowly take to the air, then suddenly begin making furious loops, their feet embedded in their bellies, out of sight, as if they had been misplaced. Straight away, they would begin building their nests in the forks of wisteria vines, where the entwined branches were most tangled. They made them with old grass they had scavenged from beneath tender grass, weaving the blades together with sedge that grew in the river. Once the nests were finished, they would return to the pasture and perch on the horses’ haunches, running their beaks slowly through the dense horsehair. The horses were fond of the mourners and would stand very still, hardly breathing. They would live together for two full weeks. If anyone tried to approach the horses, the mourners attacked them with their beaks, and the horses would lower their heads and stomp the ground with their right front hooves. When the two weeks had passed, the birds would return to find their nests full of bees that had grown fat on wisteria juice, bees they quickly downed before laying three eggs. They would sit on the eggs a few days; then the white birds would arrive. These small, mateless birds had red eyes and short, wide tail feathers. As the white birds swooped down, the mourners would scrutinize them, then attack them furiously just before they reached the nests. But the mourners would soon tire, and the white birds would manage to lodge themselves beneath the mourners’ feet and bellies and take over the nests, sitting on the eggs until the chicks hatched. Many were blood-spattered by the time they finished nesting on the eggs. If the white birds did not take possession of the nests quickly, the mourners would crush the eggs; and if the chicks had already hatched, the mourners would peck the little ones to death. The third of the mourners’ three eggs held a white bird. No one knew its origin.

When the mourners were ousted from their nests, they would drift aimlessly above the water, through the canes, until the fledglings could fly. Then they would return to the village and kill all the white birds. This would happen at night, and on that night we scarcely slept. When we got up the next morning, we collected the dead birds, nailed one to each door, and threw the rest into the river. The newly-hatched white chicks fled; no one ever heard them or saw them fly. It was as though they had been transformed into leaves, settling among the ivy. I found a white bird once and hid it in some shrubs. When I returned a few days later, it had become a swarm of maggots that stuck to your hand.

The mourners remained in the village until the end of summer, and when everything had turned blonde they would fly down the river toward the marshes. For a while some would wander back, roosting for four or five days on the slaughterhouse tower at Pedres Baixes, coming and going. When none was left, the elderly allowed us to take the nests apart. We examined how they were built and gathered the feathers that were caught in the nests.

My stepmother had a little box full of white feathers, another of black feathers. Sometimes, when we were tired of making soap bubbles in the courtyard, she would climb onto the table and take down the box of black feathers with the hand on her tiny arm. With the hand on her other arm—the one that was like most people’s—she would take out the feathers one by one, letting them drop from as high as she could. They were the mourners coming. I would collect them and pile them up on the table. Then she would take the other box and cry, here come the white birds, and the white feathers would flutter down, twisting round and round, a little slower than the black ones. The villagers used to say my stepmother was a bit retarded, but I didn’t think she was. We played with the feathers in the early autumn when no birds remained. In the courtyard beneath the bloom-less wisteria, a few odd flowers would still be blossoming, those that had not known how to bloom in time. Hidden among the leaves, they didn’t have much color. At times a weary wind would expose them for a moment, as if ashamed of displaying them.