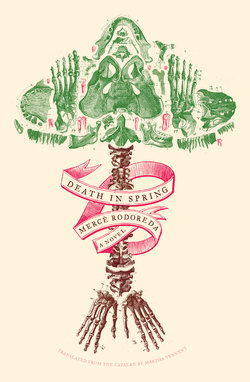

Читать книгу Death in Spring - Mercè Rodoreda - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеV

I wanted to tell him that two butterflies were stuck to his leg, but I stood still behind the shrub, shut my eyes so I wouldn’t see, and tried not to think. I didn’t open my eyes for a while, not until I could no longer hear the axe striking. The man finished the transverse line of the cross and, using the pitchfork as a lever, he was prying the bark from the tree. It was difficult. When he had separated the bark, he grabbed one of the four ends with all his might and yanked it upward. He folded it back and nailed it to the tree with a large nail, using the back of the axe as a hammer. One after the other he nailed the ends—the four parts folded into the center—-through the middle of the cross, then to the bark, the second nail above, the other two below. The trunk looked like a splayed horse. The tree was as wide and as tall as a man, and I noticed the seedcase inside. It looked slightly green in the green light of the forest, the same color as the tree trunks in the nursery. The man poked the seedcase with the pitchfork, first on one side, then the other, until it fell to the ground. Smoke rose from the gap left in the tree. The man put down the pitchfork, wiped the sweat from his neck, and rolled the seedcase to the foot of another tree. Some leaves were caught on it. He knelt down, head bowed, hands open on his knees, not moving. Then he sat on the ground and looked in the direction of the setting sun, at the butterflies.

Many of the leaves on the lower branches were partially eaten away, others merely pierced by little holes. The caterpillars never stopped chewing as they prepared to become butterflies. The man looked up with eyes he could not completely close. The air became wind. The man turned round, picked up the iron plaque, and looked at it as if he had never seen it before. He rubbed a finger over it, following the letters, one by one, until finally he stood up, seized the pitchfork and axe and headed toward the entrance to the forest, the axe on his shoulder flashing from time to time among the low-lying leaves. He came back empty-handed; and as if everything were going to recommence, the bee returned and entered the flower and the man approached his tree. He was weeping. He stepped backwards into the tree. The two butterflies had disentangled themselves from his leg when he rolled the seedcase and were now circling together above some blades of grass. They entered the tree with him, but flew out before the final entombment and landed briefly on a tree knot before moving to the soft, rubbery seedcase, where they stayed. I had turned my head, and when I looked back at the tree, I saw only the cross and the four nails on the ground. The bee was buzzing furiously before my eyes, like a pouch with yellow and black stripes. Tiny.

I stood up, rubbing my eyes from the sulphur-laced dust, and walked to the foot of the tree. Everything was still, more so than by the shrub. Everything was calm: the flutter of butterflies, the living and dying of caterpillars, the resin bubbling up and down and side to side on the cross as it healed the tree’s wound.

I was frightened. Frightened by the resin bubbling on its own, the ceiling of light hidden by leaves, and so many white wings flapping. I left, slowly at first, backing away, then I started to run, as if pursued by the man, the pitchfork, the axe. I stopped by the edge of the river and covered my ears with my open hands so I would not hear the quiet. I crossed the river again, swimming underwater because the bee was following me: I would have killed it if I could. I wanted it to be lost and alone in the dog roses where spiders lay in wait for it. On the other side of the river, I left behind the odor of caterpillar-gorged leaves and encountered the fragrance of wisteria and the stench of manure. Death in spring. I threw myself on the ground, on top of the pebbles, my heart drained of blood, my hands icy. I was fourteen years old, and the man who had entered the tree to die was my father.