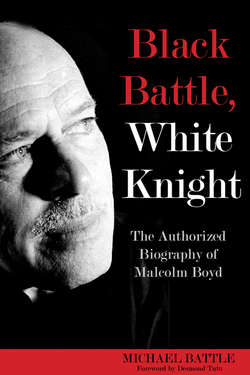

Читать книгу Black Battle, White Knight - Michael Battle - Страница 12

Why Apocalyptic Four Horsemen?

ОглавлениеAs this book was being finalized, my editor wrote me that my apocalyptic theme kept him up at night. The haunting question was: why did I decide to use the images of the four horsemen (White Knight, Red Knight, Black Knight, and Green Knight) as an organizing principle rather than writing a more conventional, chronological bibliography? I shared this question with Malcolm, who wrote, “Regarding the four horsemen. They made me want to do the book with you! A conventional biography about me would almost be ‘missing the point.’ I am not conventional. Nothing about me is actually conventional. I am not a conventional priest or a conventional writer or a conventional gay person or a conventional civil rights worker! I am different, unique, I suppose one could say ‘queer.’ I believe the horsemen ‘form of organization’ does provide more insight into my life than a ‘mere conventional biography.’”20

A life capable of synthesis of disparate identities like the four horsemen is crucial for our world today, a synthesis that no longer measures a life through the typical dualisms (for example, black vs. white, male vs. female, rich vs. poor, Asian vs. globalism) that lead to competition and war. It is interesting how Malcolm’s life represented a struggle against such dualisms. Similar to Martin Luther King Jr., when one pursues civil rights for black people you can’t avoid how such work dovetails on issues like victims of the Vietnam War and other injustices. Many of Malcolm’s speaking engagements on college campuses focused upon helping young people make such connections—that injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.

Malcolm prays, “You lost in Vietnam, didn’t you, Christ? Why do we say that we won?”21

Instead of a worldview of dualisms, Malcolm invites synthesis. As we measure Malcolm’s profound synthesis, we encounter the angst of havingto go beyond stereotype and routine. Mathematical teachers may assess the progress of their students by observing how well they reason-out a particular formula. In biology, a professor will see the results of a student’s lab. In spiritual disciplines, however, what results could ever satisfy the quest to know mutuality with the greatest of disparate identities, the creature and the Creator?

What do I mean by mutuality? Frederick Buechner helps me explain my meaning of mutuality through his definition of vocation as “the place where your deep gladness and the world’s deep hunger meet.”22 The concept of vocation proposes a kind of mutuality in which teacher and student behaviors are congruent not only with words and ideas but also with commitments and practices. A spiritual teacher like Malcolm is one who readily admits the incongruence of words and ideas as a virtue and a form of deeper knowledge. In other words, the spiritual teacher sees the world differently by learning to see “what is not there.” By learning to see “what is not there,” we learn to see “what should be there.” For example, marginalized and minority identities have often not been there or, if they are, they are invisible.

As an African-American Christian theologian, I argue that how I continue to see “what is not there” is informed by my commitment to God’s communal image. From the perspective of God’s mutuality, I practice “what is not there” in many difficult places (for example, being the only black person in my school and church)—namely, my vocation of being African American and Christian. This leads me back to Buechner’s definition of vocation. Those who teach in a spiritual way have an opportunity to develop the world into “the place where your deep gladness feeds deep hunger.” By being mutual with Malcolm, I also facilitate the revelation of Buechner’s concept of vocation in my own complex persona. This revelation of vocation honors many others in their own complex journeys in which they innately know that mutuality can only be known through vulnerability. We cannot know mutuality through conflict and disorientation. We know mutuality by first knowing what it is not. Therefore, to teach the spiritual life well requires the ability to create mutuality in such a way that both teacher and student acknowledge the impossible task of knowing God outside of the miracle of mutuality.

How then do I understand myself as a spiritual teacher? One can synthesize an answer only through the mutual search for communal ways of knowing. In other words, my quest for the Spirit always leads me to diverse communities. Unfortunately, the normative course is intended for autonomous learning among individuals only or siloed communities (for example, white, black, gay, straight, poor, or middle-upper class). For example, many persons are often irritated with the question: how are we to design spiritual experiences inclusive of diverse communities?23 To answer this question demands a response to the assumption above in which Eurocentric educational design privileges the individual or competitive communities. Patricia Cranton illustrates this assumption:

I recently discussed the idea of being an authentic teacher with a seasoned science education professor—a man who was looking forward to retirement within the next year after thirty years of teaching practice. He was almost appalled at the notion of being oneself with students. “I don’t think I could go for that,” he said, startled by what he saw as my naiveté. “Who I am in the classroom and who I am outside of the classroom are two different people. Students don’t need to know me, they need to know how to teach science.” Perhaps my raising the topic provoked images of personal self-disclosure or an emotional sharing of feelings with students, things that had no place in his mind in science teaching, but more likely, he simply saw teaching as something he does rather than who he is.24

Malcolm invites us to embrace the cultivation of learning in community that does not delete difference. This is his profound contribution as a spiritual teacher. There is an emerging consensus that the repertoires of teaching strategies most effective and responsive in socially and culturally diverse settings can be the very same strategies that are identified as characteristic of teaching excellence for traditional students. For example, the creation of space conducive for learning remains an important strategy for multicultural courses. Jack Mezirow states, “The more reflective and open we are to the perspectives of others, the richer our imagination of alternative contexts for understanding will be.”25 Malcolm teaches me that I should be just as concerned about relational interaction and communication style as I am about the content. In fact, I do not see the two as separate. Students expect the instructor to identify with them as students and as individuals in a holistic way. I have become Malcolm’s student. The crucial question Malcolm helps me answer is: how can I participate in serving the world without making matters worse in the world, especially by patronizing those I encounter? When thinking about how better to serve, one should distinguish between charity work and community service. Charity work implies “detached beneficence”; whereas community service “conjures up images of doing good deeds in impoverished, disadvantaged (primarily Black and Brown) communities by those (mostly White students) who are wealthier and more privileged.” My role as spiritual leader, taught by Malcolm, is to challenge the perceptions of both community service and charity, replacing them with spiritual and human responsibility in a pluralistic but unequal society. By doing so, community service shifts from an individualistic experience into a social responsibility.

Malcolm prays, “Help me not to be dead while I am still alive, Lord.”26

In terms of further defining community service, one may go back to 1969 to the Southern Regional Education Board in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, who defined it as “the accomplishment of tasks that meet genuine human needs in combination with conscious educational growth.” Current theorists on service learning still seem to agree with this definition, although a problem remains.27 There have been many ways to describe community service. Although descriptions of service learning appear to be politically neutral, of course service learning, as multicultural education also demonstrates, is deeply political. All of this points toward ideological considerations behind any notion of service. What moves such programs beyond “charity” work is the intentional and critical focus of spiritual work.

This biography breaks new ground in walking out on the ledge of biography cum autobiography. It offers you a perspective on a significant life both through Malcolm’s own perspective and mine. Even more, Malcolm gives us his unadulterated voice in a way that is unavailable outside this biography. At some points, however, you may not like his voice. Similar to a voice crying in the wilderness, the secret-bearer disturbs us. As we will soon learn about Malcolm’s life, some will find his spiritual direction either blasphemous or divine. I pray this book will shed more light on the divine life of Malcolm Boyd—a life that should have much more public acclaim.

Dear Michael: I like your progress. The way you are so much a part of this. In a sense, then, our dialogue, our common/shared experience. Maybe the best way in the moment is for you to start each of the different chapters and see how they lead you. And, how each encompasses you as well as me.

Clearly, you need to flesh this stuff out (for example, see the trove I gave you of old papers, etc.) What may help most of all is the way EACH CHAPTER seems to grow and develop in its own way.

Most interesting, I think, will be the chapter on Celebrity. It is the cornerstone. Celebrity has changed the world. (Is it a virus?) You have the opportunity to explore the “Hollywood” side of this in my material, and how it deeply affected my life. Then, utterly ironically, how I “happened” to write a book that became not only a best-seller but a celebrity itself. Then, link this with you and Tutu (irony upon irony, if you will). So we’re in the midst of this. Where does it lead? What can we do about it? Can we make it work for “good” instead of our being simply slaves or victims of it? I think you need to shut out the world briefly, concentrate, focus, and do a damn fine first draft of the Celebrity chapter—which should, in reality, lead off the book itself. It gives the book its glamour, its immediacy, its hard challenge, its utter relevance. It simply combines sacred and secular by DOING it instead of merely “talking about” it. . . .

You need to be unafraid to bring yourself into the center of things. Including your fears, inadequacies, confusions, awakenings. In a sense the book is a thrilling trajectory of spiritual direction as well as a biography. You’re looking into your own life as well as into mine. So what does “success” mean? What can/does one do with “fame”? Include Tutu. “What’s it all about, Alfie?” But why are “success” and “fame” so often suicidal and self-destructive? (Why do they often seem to bring out the worst in people?) Indeed, why are they seen as selfish? How is this related to Jesus—and, especially, to the cross?

There is so much involved here! Isn’t it fascinating????28

So, here, in this book, is my response to Malcolm. This is not just another black book or gay book. This book is born on the miracle of the election of Barack Obama, which no doubt makes both Malcolm and me reflect more deeply about the repercussions of the Civil Rights Movement. For example, is it over? Also, this book emerges in the threshold of the debate for full inclusion of gay and lesbian persons. Can they marry? Is marriage a good idea? And could a gay or lesbian person be a head of a church? The answers that a reader discovers in the life of Malcolm Boyd are deeply contemporary (he is way ahead of his time)—and more importantly deeply divine.

Beyond getting to know Malcolm as a modern-day prophet, I have now enjoyed the privilege of receiving spiritual direction from Malcolm. Because of the life of God that I have learned from Malcolm, I think it is appropriate that I give some of this spiritual direction to the reader as well. I, therefore, write this book as it is intended to be read—with new perspective while at the same time testing current and past realities. So, read this biography as a focused reflection upon a person conscious of unnecessary hierarchies and false gods. By doing so, the genius that you will discover is that none of us are called to worship false gods.

Dear Michael: I realize for the first time what an extraordinary book you have here. It is a part of (has grown out of) spiritual direction. Quite aside from the book itself, this is simply extraordinary.

The book is not only my biography. It is also your autobiography in numerous ways. You must place yourself (as well as myself) in these pages. I believe you already are doing this. So it can be informal in places, intimate, unpretentious, natural, even conversational. This is the progression of your own spiritual development growing out of our conversations and our looking together at similar issues and themes. Here, the very title of the book comes alive. I’m wondering if perhaps the subtitle should be changed from “A Biography of Malcolm Boyd” to “Biography-cum-Autobiography.”

This can make the book itself a matter (and example) of global and international interest. This can be of intense interest. What is going on here? Something altogether fascinating, unique—that teaches virtually everyone new directions, insights, questions, approaches. It also opens up countless “old” questions and dilemmas, illustrating how to approach them in altogether fresh ways, with new attitudes and insights.

SO you place yourself in the book from the outset. (I think you’re doing this.) There’s dialogue (with me) instead of monologue. As we trace our public course, I’ve also offered you—step by step, detail by detail—spiritual direction. I love the scope and naturalness and depth of this. Actually, all sorts of people in all sorts of places may want to read and share this book.

Your chapters are your own genius. Pursue them. (Talk about gravitas.) Next week I’ll have an opportunity to delve into chapter one and respond specifically to you in detail.29

3. Malcolm Boyd, “New,” e-mail message to author, October 25, 2010,

4. Malcolm Boyd, “Funky,” Yale Daily News, February 19, 1969.

5. Conversation I had with Malcolm during spiritual direction, January 6, 2011.

6. Malcolm Boyd, “A Bit More on Brokeback,” e-mail message to author, May 7, 2010.

7. Carol M. Arney’s Interview with the Rev. Norio Sasaki, March 2, 1995.

8. Carol M. Arney, The Episcopate of the Rt. Rev. Harry S. Kennedy, Bishop of the Missionary District of Honolulu, 1944 to 1969 (Honors Paper, The School of Theology, University of the South, 1995), 45–46.

9. Malcolm Boyd and Paul Conrad, When in the Course of Human Events (New York: Sheed and Ward, 1973), 22–23.

10. Malcolm Boyd, “Maybe most important . . . you,” e-mail message to author, December 21, 2009.

11. Boyd and Conrad, When in the Course of Human Events, 34–35.

12. Malcolm Boyd, “Have finished chapter,” e-mail message to author, January 13, 2010.

13. Malcolm Boyd, “Big News,” e-mail message to author, August 17, 2009.

14. Malcolm’s handwritten letter to “Rob,” October 20, 2010.

15. Malcolm Boyd, “Rosebud,” e-mail to author, February 17, 2009.

16. Malcolm Boyd, “Post-Thursday thoughts,” e-mail message to author, August 14, 2009.

17. Parker Palmer, The Courage to Teach: Exploring the Inner Landscape of a Teacher’s Life (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1998), 21.

18. Michael Battle, Reconciliation: The Ubuntu Theology of Desmond Tutu (Cleveland: Pilgrim Press, 1997); The Wisdom of Desmond Tutu (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2000); and Ubuntu: I in You and You in Me (New York: Seabury Press 2009).

19. Tutu’s undated handwritten speeches, “Perspectives in Black and White.” Tutu illustrates further with this story: “A little boy excitedly pointed to a flight of geese and shouted, ‘Mummy, Mummy, look at all those goose.’ ‘My darling,’ Mummy replied, ‘we don’t call them gooses. They are geese.’ Then the little darling, nothing daunted, retorted, ‘Well they still look like goose to me.’”

20. Malcolm Boyd, “In Response to Dennis Ford,” e-mail message, February 3, 2011.

21. Boyd and Conrad, When in the Course of Human Events, 26–27.

22. Frederick Buechner, Wishful Thinking: A Seeker’s ABC (San Francisco: HarperSan- Francisco, 1993), 119.

23. When I attended a conference in 2002, Apiwa Mucherera, assistant professor at Asbury Theological Seminary, phrased this as a “Here we go again” mentality in which one may dismiss the other before she even speaks.

24. Patricia Cranton, Becoming an Authentic Teacher in Higher Education (Malabar, FL: Krieger Publishing Company, 2001), 43.

25. Jack Mezirow and Associates, Learning as Transformation: Critical Perspectives on a Theory in Progress (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2000), 20.

26. Boyd and Conrad, When in the Course of Human Events, 14–15.

27. The following educational theorists contributed deeply to the integration of service learning into the academy: John Dewey, Jean Piaget, David Kolb, and Paulo Freire. See C. W. Kinsley and K. McPherson, eds., Enriching the Curriculum through Service Learning (Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 1995).

28. Malcolm Boyd, “Black Horse of Famine,” e-mail message to author, September 4, 2009.

29. Malcolm Boyd, “The Book,” e-mail message to author, July 22, 2009.