Читать книгу Black Battle, White Knight - Michael Battle - Страница 9

INTRODUCTION Horse with No Name

ОглавлениеGrowing up, one of my favorite songs was “A Horse with No Name,” written by the rock group in the seventies known as America. It’s curious that a forty-seven-year-old African American like myself would like such a song. After all, the stereotype is for me to love Luther Vandross, Whitney Houston, and Barry White. Defying the stereotypes, I found “A Horse with No Name” to be a brilliant, hypnotic song. The chorus in particular invites you into the subject matter of this book—the boundary-breaking life of Malcolm Boyd. The hypnotic chorus of the song recalls imagery of a desert and a horse with no name. The rider feels good to be in the desert where you can remember your name (out of the rain) where no one can give you no pain. Perhaps this imagery was recalled in some drug-induced state of a typical rock group, or maybe it was gained through the insight that all of us need guidance out of a wilderness that often becomes known as ordinary life. Strangely enough, I found myself in such a wilderness listening to a voice crying in the desert.

Like many folk musicians and famous musicians, Malcolm’s voice was boosted in strange places. One such place was called the “hungry i.” The hungry i was a nightclub in San Francisco, owned by Enrico Banducci. The mysterious name “hungry i,” with the lower-case “i,” is said to represent “intellectual.” On other accounts, Banducci came up with a Freudian meaning implying “the hungry id.” In a more humorous account, the sign “the hungry i” simply was not finished in time for the club’s opening, and next-day reviews in the San Francisco papers cemented the name for all time.

The club was located at 546 Broadway Street, and was instrumental in the careers not only of Malcolm but for the actor/comedian Bill Cosby; the Kingston Trio, who recorded two famous albums there, including the first live performance of their version of “The Lion Sleeps Tonight”; and jazz legend Vince Guaraldi. They were all given career boosts from their appearances at the hungry i.

When the comedy and folk music scene declined in the mid-1960s with the rise of hard rock and Vietnam War protests, Banducci closed the club and sold its name to a topless club at another location nearby. Banducci and many of the club’s performers reunited in 1981 for a memorable one-night performance, captured in the nationally televised documentary hungry i Reunion, produced and directed by Thomas A. Cohen and featuring separate reminiscences by Maya Angelou and Bill Cosby.

Malcolm’s voice crying from the wilderness started in strange places like the hungry i. But what was he saying at the time?

On a chalkboard in Malcolm’s office is this printed notice: “Who Said?” There’s a statement that could have come from one of three persons: “It is better to know some of the questions than all of the answers.” The three persons listed who might have made the statement are Malcolm Boyd, Gottfried Leibnix, and James Thurber. Maybe all three came up with the words. I don’t know. Whoever said the words, they accurately convey Malcolm’s voice.

Openness to change seems essential for Malcolm. Change is the answer for bureaucracy without focus, irrelevant answers to nonquestions, continuing to do things “as they have always been done,” a jaded attitude, and a numbing loss of spiritual energy. A classic Japanese film, Akira Kurosawa’sRashomon, portrays the human dilemma of trying to arrive at “the truth.” The film depicts the rape of a woman and the murder of her Samurai husband through the widely differing accounts of four witnesses. The stories are mutually contradictory. These four perspectives are also instructive of the four horsemen who frame the texture of Malcolm’s life. Seeing life from different perspectives often causes panic in the seeker for one kind of truth. This brings up the classic question posed by Pontius Pilate in his confrontation with Jesus: “What is truth?”

Malcolm writes me:

Fundamentalism comes up with “one” irrevocable answer. There is a singular interpretation. Yet in multilayered and highly complex life, I choose to remain open to various interpretations rooted in complex and dismayingly different views and experiences. This can extend to looking at a singular person or event as “good” or “evil,” “promising” or “hopeless,” “creative” or “destructive,” a “positive” sign or a “negative” one. I never like “either/or.” I prefer “both/and.” Is the above clear? Do we need another sentence or thought? If so, maybe you can come up with it. I just find life itself so amazingly “open” instead of sealed shut and “closed.” Usually it includes possibilities. Anyhow, I thought we should get Rashomon in here.3

Indeed, Malcolm sought the truth—come what may. His voice in doing so was often heard as caustic and jarring. “I’m white,” Malcolm said. “Did I murder six million Jews in Nazi Germany? Did I lynch, castrate, starve, burn, knife, hang, disembowel, rape, and murder thousands and thousands of black people in America? Do I stand today in the way of black progress, social equality, and liberation in the U.S.?” 4

This voice attracted me to the desert. It was an apocalyptic voice, irritatingly honest, calling for conscious attention to the ills of the world. It was the voice of an apocalyptic horseman galloping in the desert. Malcolm’s was a voice demanding that he better study (and learn) White history because his identity was shattered when he confronted the invisible among us—those lesser identities that Ralph Ellison referred to in the Invisible Man—such as undocumented workers and the downtrodden. Malcolm attracted me to the thought that the White Experience has been built on labyrinthine myths that now drive him to his fellow compatriots like white psychotherapists who corroborate such myths in the White Experience. Malcolm put it this way, “I try to look deeply into the White Experience but am unnerved by what I see. I had been told it was all apple pie, prayers, cleanliness, decency, morality, righteousness, goodness, a just but not overly loving god (you know, a father image), law, order, converting the natives, and it wasn’t. Am I therefore a masochist instead of the righteous ruler? What is to be ‘my role’?”5

These were my same questions, but unlike Malcolm, an eighty-eightyear- old, white, gay, celebrity priest, I was a black, forty-six-year-old, married heterosexual wannabe celebrity priest. I am an African-American Episcopal priest. For many of you, this is a strange identity, especially given the context that I should not be who I really am writing this book. Wouldn’t the reader think that a white, gay liberal is most qualified to tell Malcolm’s story? I don’t think so. Because of who Malcolm is (not either/or but Rashomon from all angles), it fits that I write this book—even if one of the crucial aspects of Malcolm’s life was his coming out as gay during a violent and turbulent period in human history. Malcolm provides me the following account that makes his life all the more vivid and real. It is contained in a letter Malcolm writes to a friend:

Dear Chris: It occurs to me that, as gays with tragic histories and innumerable problems linked to the past, we are a bit like Zionists confronting—again and again—the Holocaust. Is it forever the Rock of Gibraltar, the Tsunami that strikes without warning and casts a giant shadow, indeed, one’s very history imbedded within oneself. This is far more than a question of a “happy ending.” This is essential being. But the question remains: can we move forward, seek and perceive a new direction, achieve and maintain some solid and meaningful balance in one’s life?

A night that I visited Cheyenne, Wyoming, in 1959 remains locked in my memory. Of course, I was in Brokeback Mountain territory. And Matthew Shepard territory. I drove up to Cheyenne from Fort Collins, Colorado, with a male friend. I didn’t know him well, assumed he was not gay. We were not on a gay seek. I felt vulnerable because, in a sense, I was always on a gay seek (even if I buried that deep in my consciousness). We drank a lot; I think it was beer. I’m sure our visit had no common purpose. (Why were we making this visit to Cheyenne?) Clearly, I was extraordinarily vulnerable. I felt I couldn’t let my guard down. The guy was a part of a social structure in which I moved as a chaplain at Colorado State University.

At that time I felt sure I would never be able to come out. It simply wasn’t a remote possibility. I was imprisoned. Yet here I was drinking a lot with this guy and aware that, as a closeted gay man, I was in deep enemy territory. I really had to watch my P’s and Q’s. Not let my guard down. Not react to anything. And then the sense of actual danger grew in me. This was truly “enemy territory.” We didn’t stay the night but drove back rather late. I have some vague memory of his making a possible sort of pass (in the context of a lot of alcohol) that I knew I had to ignore. He was a colleague at work in the university system. He was political. My best defense was to be free from gossip and innuendo in “the man’s world” in which I found myself. So that night in Cheyenne was hellish because it inadvertently brought up so many issues, made me confront my reality once again (hell, why go through that shit again?), rendered me helpless, and all this was taking place in the deep, deep shadow of—yes—Brokeback Mountain territory. . . . So this is another slice of gay history, gay experience. But even in an ambience of male bonding-cum-alcohol, it was necessary to keep the lid on.

I wonder what a few of those guys who later killed Matthew Shepard thought of us, two men together visiting their bar, strangers from the nearby university, good-looking men without women. Why were they here? What were they looking for? They were strangers. Do we want strangers like that to come into our turf? Indeed, this is a part of gay history. Can we lift the shadow a bit? Instill good memories into bad? Become a bit more trusting, a bit more positive? In fact—whether it’s a holocaust or a Brokeback Mountain—dare/can we surrender a chunk of our vulnerability?6

Constantly in writing this biography, Malcolm pushed me toward vulnerability, which in turn created a common ground for seemingly disparate persons like Malcolm and me. Our common ground was more than being priests. Even if you are not religious, what I am about to say is fascinating because it points to how boundaries around human identity have changed. What I mean is: the Episcopal Church has historically meant a white European church in which my kinds of identity (for example, Negro, colored, black, African American) were not anticipated as becoming vibrant members. Surely, the original founders of the colonizing Church of England did not foresee my ancestors, African slaves, as the average Anglican. And yet, today, the mean average of an Anglican around the world is a thirty-six-year-old Nigerian woman. An African who is an Anglican is a crazy juxtaposition. An African Anglican is really an oxymoron since for much of human history, these two identities could never be mutual.

Malcolm’s genius is in how his vision of the world and God’s creation was such that there could be room at the table for all people. I remember an example of this when I was having dinner with fellow Anglicans at a church conference. To a table full of strangers, I mentioned that I was doing this biography on Malcolm. Even though I shouldn’t have been, I was surprised that the majority of the table knew about Malcolm and even more that a couple at the table told me that they wouldn’t have gotten ordained in the Anglican Church if it had not been for Malcolm. One of the persons who made this confession sent me information from an honors thesis she was writing. The thesis was about a Hawaii-born man named Masao Fujita, of Japanese ancestry, who entered the process to become an Anglican priest in 1950. After interrupting his seminary training to serve in the military in 1954–55, he was ordained in 1957. In isolated, rural areas Fujita served Grace Church, Molokai, and the Kohala Mission on the north side of the Island of Hawaii.

It was on the mainland in 1963 while doing postgraduate study that he visited Malcolm, with whom he had become friends while in seminary. During his visit Masao related to Malcolm that it was impossible for an American of Japanese ancestry to get a good church position in Hawaii, because all the good spots went to Caucasians. Shortly thereafter an article appeared in the Los Angeles Times accusing the Episcopal Church in Hawaii of racism. Malcolm wrote the article. Though the story never got major play in Hawaii, the Bishop of Los Angeles sent Bishop Kennedy a copy of the article. Reacting with horror at this accusation, Bishop Kennedy called the other clergy of Japanese ancestry into a private meeting at a clergy conference. Without showing them the article, he asked, “This isn’t true, is it?” Another priest, Norio Sasaki, relates that, “We were all scared to disagree with the Bishop. I know that I was just out of seminary. Now I think that maybe I didn’t support Masao enough.”7. In retrospect today, Masao’s concerns were difficult to hear by those in power. To criticize a Bishop in the Los Angeles Times caused much tension, especially among those who valued good public appearance as essential. Yet, there is another aspect to be considered. Masao and Bishop Kennedy, coming from different worldviews, did not have the same perceptions of vocation. Similar to Malcolm’s insights about Rashomon, one of the chief tasks in life is to understand each other coming from different world views. Bishop Kennedy had valued his days in small, rural missions as some of the happiest days of his life. Masao wanted an up-and-coming city church as much as any other priest in Hawaii in those days. Also, it was not custom for people from a Japanese culture to confront their superiors directly with a complaint or criticism. Probably if Malcolm Boyd had not written the article, Masao Fujita would never have complained to the Bishop—and improvements in his vocation may not have manifested.8

Doing my research on the life of Malcolm Boyd led me continuously to such strange occurrences of meeting many people whose lives were deeply influenced by Malcolm’s voice crying out in the wilderness. I found myself in this new strange territory singing that rock group’s reframe, “I’ve been through the desert on a horse with no name.” Of course my context was different. The black experience was hard to name in a church with a predominantly white British identity. The difficulty of having no name in this world was compounded by the fact that I didn’t want to blame white people. After all, everyone is trying to survive in the desert. Who needs another voice of blame when you’re simply trying to drive your kids to school, survive an economic meltdown, and keep your cholesterol under control? Nevertheless, I felt like I was playing a role. I was the expert on black experience. I was the token voice for the appendages of history in which the colonized represented reconciliation with the true church (of European descent). This was the sarcastic spirit clanging in my soul.

Malcolm became my spiritual director. “I learned from black liberation,” Malcolm told me, “that I do not have to play a ‘role.’ It is not only my black brother who can be free. I, too, can taste the freedom, liberation, release, and meaning that transform my existence into a life.” In our regular sessions of spiritual direction, Malcolm taught me that God gave me freedom to be human, hence my new name, human being. In my freedom as a human being, I can transcend roles that would imprison me—if I have enough courage to cut myself free from ties in the mind, the body, the personality, and the society.

Malcolm prays, “Whoever receives one such child in my name receives me.” Jesus, help us to receive you.9

Although I grew up in North Carolina when segregation was a fresh memory, Malcolm taught me that I have the power to turn away from a white god who resides in temples of whiteness, white purity, white truth, and white holiness without having to feel guilty for hurting white people’s feelings. After all, Malcolm is white—and his feelings weren’t hurt. But the key to Malcolm’s spiritual direction was that in my new freedom, I shouldn’t go to the opposite extreme in my freedom and turn to a black god who resides in temples of blackness, black purity, black truth, black holiness. Nor, really, do I need a green god, a red god, a yellow god, or a blue god.

Also, I do not need a white ghetto, a black ghetto, a green ghetto, a red ghetto, a yellow ghetto, or a blue ghetto. Malcolm states strongly, “I will fight all these lousy damned ghettos. Because I know that I cannot speak of freedom as an individual if I cannot live in a free society.”

“But Malcolm, why should I be black in a white church, a white universe? Shouldn’t I fight against this idolatrous worldview?”

“No. I do not have to fight anybody. Anger is almost as much a landmine as self-righteousness. Battles concern me only within the context of war. I must convey my humanness to others, not my ‘Christianity.’ I must convey my humanness to others, not my ‘Americanism.’”

“How can I do this if I am not human—if I have no name in some human systems?”

Malcolm answers by describing his own experience. “To be human, I must understand that my whiteness is secondary, along with my ‘Christianity’ and ‘Americanism.’ As a human, I have human contacts with other people. I have as many close black friends as white ones; our blackness and our whiteness are vitally important in defining our individual humanness and our social relationship, but the blackness and whiteness finally do not separate us but instead become the factor of binding our painful humanity together. I cannot truly enter the human experience if I do not comprehend (and partially live in) the Black Experience as well as the White Experience. The human experience is, in its fulfillment, a unity.”

Eldridge Cleaver, a famous black power activist, speaks of a world that has become virtually a neighborhood. Martin Luther King Jr. calls it a World House. Both Cleaver and King conclude that if this planet is to survive, the concept of humanity segregating is really something that can’t continue indefinitely. “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere,” preaches King. Archbishop Desmond Tutu puts it this way, “Humanity is inextricably linked together. A person is a person through other persons.” I think this is why one of Tutu’s best friends is the DalaiLama of Tibet. Strange relationships develop when the worldview is cooperation rather than competition.

Malcolm concludes, “I do not wish to be naïve about my humanness or my whiteness (indeed, my ‘Christianity’ or ‘Americanism’). . . . I do not speak of utopias, I am not even explicitly idealistic. Survival is hard pragmatism. Freedom and liberation are hard as nails, not airy generalities. If a black person abrasively rejects me—on the basis of my whiteness, not on the basis of knowing Malcolm as a person—it is inhuman and dehumanizing of me to react in outrage, protest, cries of self-pity and deprecation, and unholy preachment. We can, the two of us, maintain our humanness in the creative tension of separation. Isolated we will not be, for our mutual consciousness of one another is a burning thing. And, if we seek a mutual goal, we can remain human within tactical separation.”

Malcolm refused to be separated from all black people at the height of the Civil Rights Movement. With those black folk open to friendship with Malcolm, he joined the struggle, the Civil Rights Movement to join Black Experience with White Experience (even a Martian would have to be treated well!). “After all,” Malcolm says, “it is the funky human experience that defines, kills, and resurrects us.”

I think it is in this realization that I cannot be human alone that I approached Malcolm Boyd to be my spiritual director. I knew I needed someone, himself complex enough, to help me navigate turbulent waters of identity. I needed someone with a strong name, a strong identity, who could help me know my own. I feel as though I am a member of a church like America’s song “A Horse with No Name”—a church whose name has changed or perhaps, no longer has a name. This journey is key to this book.

Malcolm writes me:

Dear Michael: I don’t know how you’re literally planning the book. It seems to me you need a short, succinct introduction to follow the foreword—and precede chapter 1—in which you introduce yourself, explain “who” you are and “why” you’re writing this book. The entire book hinges on this.

You need to move deep, deep, deep into yourself. Tell us your story/stories. Total authenticity here. The reader must “know” you. Otherwise you are just another abstract “thing” such as an “Episcopal priest” or “a scholar.” Actually, why did you become both? What else did you become? What does race—and faith—have to do with it? What is our relationship (yours and mine) and what is something strange and esoteric called “spiritual direction”?

This involves the relationship with me, too. Where/when did you first hear of me? What have been your feelings or impressions? I remember when we met and when you asked me to be your spiritual director. When did you think of writing the biography? Why?

This leads to some self-examination in terms of your own life. (A writer must be open and vulnerable.) Where are you heading in your own life? (What do you want? What do you feel God wants from you?) “How” do our lives intersect? (Do they intersect in the book?)

Once this kind of thing is firmly established in the reader’s mind, you can refer back to it again and again as you progress through the entire book. Finally, what are you progressing toward as you complete the book? Will there be any “answers”? What will be the big questions?

It boils down to that classic line in the classic film Alfie. “What’s it all about, Alfie?” The book is a terrain. You are moving (across) it as a kind of pilgrim or wanderer. What in your past has motivated you to do this? What skills or insights do you possess? Have you a sense of a destination? (What form might it take?) I’m really talking about your whole life—the wholeness (holiness?)—of your entire life experience.

I’ll look forward to what you will be sending me in the coming days. All best. . . .10

Whenever I do speaking engagements, usually on the themes of reconciliation and human spirituality, I like to tell my audiences that the reason I am an Episcopalian is because I grew up in the black church denomination National Baptist, and attended the University of Notre Dame my freshman year—being Baptist at a 99.8 percent Roman Catholic University cooked me into an Episcopalian. The confluence of Baptist congregationalism and Catholic ubiquity set me on a course for an Anglican middle way.

As a result of my own anomalous life, this biography was born in spiritual direction, looking for God in the desert. As a spiritual director myself, I realize the demand of the naming process—of learning your real name. After all, there are so many stereotypes given to me as my names. In many ways it’s easy for me to just accept them and move on. It’s hard to find those individuals who refuse the false names, the masks we hide behind. I needed such an exemplar to know my own unusual name.

Similar to the beauty of the rite of passage of a Native American vision quest, I set out on a journey in search of a sage who could guide me.

Being an unusual person myself, I required an unusual spiritual director. I was picky. So, when I needed to find God, I approached Malcolm Boyd.

Being an unusual person myself, I required an unusual spiritual director. I was picky. So, when I needed to find God, I approached Malcolm Boyd.

Malcolm prays, “Enable us to see complex people instead of simple images, Christ. Enable us to be complex people instead of simple images, Christ.”11

Look at the popular black singer Tina Turner, for example; she’s a Buddhist! Even if you do know Malcolm Boyd and recognize no irony in my voice as his biographer, the burden is no lighter in trying to convince you to read a biography in which you may feel uncomfortable because, for many, finding God in Malcolm is blasphemy. How could anyone find God in a gay, political, rebellious, celebrity priest? I say to all of you who approach this biography from a myriad of perspectives, come into a desert with a horse with no name and I think you will be surprised by the new identity you discover in yourself and in Malcolm Boyd. The irony, of course, is that Malcolm has a world renowned name. Malcolm bashfully writes me:

Apropos of nothing, I’ve listed a few major and fascinating personalities with whom I’ve (to say the least) “interacted” on one occasion or another. In other words, there are “good stories” here. The Washington Post’s Katharine Graham (“America is not an imperial power,” she thundered at me as she bolted from the TV studio in Chicago). Rosemary Radford Reuther, the Catholic theologian (and great person) who, in a meeting in East Harlem, announced: “The problem with Malcolm is he wants to be loved.” Well, yes, damn it—as a faggot and queer and leper, YES, I DID want to be loved!!! Hugh D. Auchincloss, Jackie Kennedy Onassis’s step-father, muttered to me in Newport Beach: “Why don’t you write some prayers for stockbrokers?” You already have in the manuscript the classic scene in Hollywood where I come too close to opening a window and shouting at Howard Hughes and Samuel Goldwyn to “SHUT UP!” And there’s an utter classic scene with sainted Mary Daly that is almost too awful to recount. . . . Where would a paragraph of these fit in the manuscript? Oh yes, and the time when I introduced Bishop Donegan of New York to the vodka martini??? (Which he then drank every evening for the rest of his life). I’ve marked the entire chapter in each instance of doing editing. So I’m ready for our meeting Friday 15 at 1. All best . . . M.12

What’s fascinating about Malcolm is that although his name is great, it can evoke pain.

Malcolm once told me about a particular portrait of him painted by world-renowned artist Don Bachardy. Malcolm wondered what the artist would see when he examined him closely, paintbrush in hand? Malcolm drove to the artist’s home feeling like the proverbial Cowardly Lion. Sitting in a chair facing the artist, with a view of the ocean over Malcolm’s shoulder, Malcolm sat for his first portrait. For the second, Malcolm sat on a couch and propped himself against pillows. For the third he lay down on a couch with his head resting on a pillow. Later, when Malcolm saw the portraits, he liked the first and third. But he had an immediate negative reaction to the second. Malcolm explains, “I didn’t like the ‘me’ it reflects.” That is to say, it didn’t resemble Malcolm’s own idea of what he looked like—or wanted to look like. Malcolm concludes, “Yet I had to face the fact that perhaps this picture showed a part of me I chose to reject. Maybe I didn’t want to deal with this person (a part of myself) at all. As a further complication, was it possible I hadn’t a clue how this person could be an integral part of ‘me’? Who am I? This remains a central question in all our lives.” When asked specifically if Malcolm could identify what “part” of him he found in the portrait that he didn’t like, he responded, “No. Only the awareness or an opening up to a different reality of self that you didn’t see before often scares you.”

Malcolm was born in New York City in 1923 as the child of a prosperous investment banker. His parents divorced by the time of the Depression and he went with his mother to Denver, where he graduated from high school in 1940. Bronchial trouble kept him out of military service during World War II and led him to the University of Arizona. An indifferent student, he graduated in 1944 with a major in English and a minor in economics.

From Arizona he went to Hollywood and a $50-a-week job with the Footer Cone and Belding advertising agency. After directing a homemakers’ hour on radio, he moved to Republic Pictures, where he became a publicist, an excellent entry position in the film industry. Republic Pictures was (and still is, in-name-only) an independent film production-distribution corporation with studio facilities, operating from 1934 through 1959 and best known for its specialization in westerns, movie serials, and B-films emphasizing mystery and action. They were also responsible for financing one Shakespeare film, Orson Welles’s Macbeth (1948), several films directed by John Ford during the 1940s and early 1950s, and for developing the careers and star-status of John Wayne, Gene Autry, and Roy Rogers.

By 1949 Malcolm was in New York and associated with Mary Pickford and Buddy Rogers in a venture organized to package television programs. Two years later, in 1951, he was in a hotel room in Tucson, Arizona, spending a weekend with the Bible. Shocking his friends and amazing Hollywood—he had seemed to be only starting a promising career—he decided to enter the Church Divinity School of the Pacific in Berkeley, California.

Three years as a seminarian were followed by a year at Oxford University. In England he discovered an Episcopal mission ministering to the needs of workers in Sheffield. From England he went to an ecumenical institute in Geneva and on to Union Theological Seminary in New York, “where every question was asked.” Then he was back in Europe at the Taizé community in France, learning firsthand about spirituality and worker-priests.

Malcolm’s first church was in Indianapolis. There in 1957 he took charge of a 150-member, all-white parish in a neighborhood that had become largely black, and there he became aware of the depths of the race problem when he traded altars one Sunday with a black priest and “the biggest question in his parish was whether they would receive the chalice from a nigger’s hand.”

1n 1959 he became a chaplain at Colorado State University and received nationwide attention as well as his first ecclesiastical rebuke when he moved his ministry off-campus into the Golden Grape Coffee House and a student beer joint. Bishop Joseph Minnis decried “priests going into taverns and drinking and counting it as ministry.”

Malcolm got the message that his kind of ministry was perceived as at best unorthodox and at worst blasphemy. Malcolm felt like he was expected to conform, to be quiet, and not to question or criticize anyone over him. In particular Malcolm vied with the power of Bishop Minnis. No longer did Malcolm feel welcome in the church by Bishop Minnis. Concurrently, Malcolm got the divine message about racism and the need for faith and religion to hit the streets. In 1961 Malcolm went on a Freedom Ride with twenty-six white and black priests who traveled from New Orleans to Detroit, where they attended an Episcopal General Convention.

From 1961 to 1963 he served as a chaplain on the Wayne State University campus in Detroit. While there he wrote five plays about racism (one performed on television). At one point, Malcolm took up modern dance when an essay of his on Christianity was being choreographed. But his writing got him into trouble, too, and Michigan Bishop Richard Emrich criticized Malcolm for using the words “damn” and “nigger” in his plays.

Early in 1964 Malcolm found friendly shelter when then Suffragan Bishop Paul Moore Jr., of Washington, D.C., took him under his wing and made him assistant priest of the historically African-American Church of the Atonement. From that base, Malcolm traveled to as many as 125 campuses in a year and became an unofficial chaplain-at-large to college students.

This initial portion of Malcolm’s biography is an attempt to really see Malcolm, and in turn see ourselves. In the African sense, I want to know his real name—his real identity. That’s the beauty of biography; the journey of a life always invites the discovery of self-identity for the reader as well. Much of this journey is about the reconciliation of disparate identities articulated so well by Malcolm: the “me” I want and the “me” I try to avoid. Where Malcolm helps all of us is in his tenacity not to rest until there is a synthesis. Although he calls himself the Cowardly Lion, Malcolm is a cauldron of courage. As you will learn, Malcolm’s tenacity requires sustained courage and grit. To illustrate this, one of the best descriptions of Malcolm comes from his friend Paul Monette, who won the National Book Award in 1992 and died too young at age forty-nine. In Monette’s book Last Watch of the Night, he describes Malcolm in these words: “He wrestles God as Jacob wrestled the angel, till the breaking of the day.”

In this biography, I seek to reconcile the God so easily encountered in Malcolm with the angst in Malcolm’s unique life due to his encounter with racism and xenophobia, especially toward gays. Malcolm’s life is the image of God in that there are so many different perceptions of him and yet there exists one large geographic identity. To see such identity requires a quiet place, like a desert. Malcolm tells the story of sitting under a 400-year-old tree and learning to not use words. The tree didn’t move, but Malcolm crossed his legs. The tree simply remained there with him. In so being, Malcolm came to realize that, like him, the tree’s identity isn’t simple at all but is immensely complex. Malcolm and the tree share this complexity in common. However, by its very existence, the tree makes the strongest possible statement. It is anchored here and now. Malcolm states, “I ask the same for myself.”

Before we begin the biography in earnest, more context is still in order. I first heard about Malcolm when I lived with Desmond Tutu in Cape Town, South Africa. Tutu modeled for me the health that derives from staying in spiritual direction. Tutu’s tremendous impact against apartheid would not have occurred apart from his own deep spirituality. With the backdrop of Table Mountain outside, I sat in Tutu’s office looking through his writings and constant requests for book endorsements. On one particular day, I ran across a book sitting on Tutu’s desk entitled Gay Priest: An Inner Journey, written by Malcolm Boyd. Even in 1993, I found this a provocative title. Neither Tutu nor I are gay, but as I explored why this book was in Tutu’s office, I discovered that Malcolm had blessed both me, an African-American heterosexual, and Tutu, a world-renowned African saint. We were deeply impressed by the Holy Spirit in Malcolm’s life. As I look back to 1993, this is where the seed for this book was planted. Malcolm recognizes this seed as well.

Dear Michael: Since the book is about US (the two of us, our spiritual direction work, our mutuality, our connectedness), it seems essential that you include Tutu in the celebrity chapter.

He is a great figure in your life—and also in the world. Such links need to be made. Actually including him should make your work easier because obviously you have material about Tutu on hand that you can incorporate here. This heightens interest and excitement, assists the task of communication, and draws you closer into your necessary orbit. The book becomes ever and ever more fascinating. It’s far more than “a biography.”

All this is becoming infinitely more fascinating than either of us initially had in mind. A truly original, creative work.13

Fortunately, I didn’t need a spiritual director for my two years in South Africa because I used Tutu’s own spiritual director, the Rev. Francis Cull. It was fascinating working with Cull, who resembled a character from Tolkien or C. S. Lewis stories. His very presence stimulated a sense of unusual reality which helped in spiritual direction. It was easier to talk about God and unusual things with Francis.

When I returned to the United States in 1995, I no longer had a spiritual director. And sadly, my Nome-like spiritual director had passed away. As my public ministry developed as a professor of spirituality, retreat leader, theologian, and Episcopal priest, I was living in the hypocrisy of giving spiritual direction without being in it myself. These years accumulated because I was too picky and could not settle upon an ordinary spiritual director. One day, in August 2007, as I was walking through the Cathedral Center in the Episcopal Diocese of Los Angeles, I overheard someone say that Malcolm Boyd gave spiritual direction. Malcolm became my spiritual director.

How Malcolm discovered his gifts as a spiritual director was interesting and surreptitious. It wasn’t as if he signed up for a course in spiritual direction or climbed a Tibetan mountain to attain a particular acumen to do it. In the 1980s Malcolm served as an associate priest at the parish of St. Augustine by-the-Sea in Santa Monica, California. The Rev. Fred Fenton, rector of the parish, invited Malcolm to “come out” as a gay priest in his first sermon there. Some people walked out and some pledges were cancelled, but Malcolm remained there for nearly fifteen years. In past years Malcolm had counseled dozens, if not hundreds, of men and women in Indianapolis and Colorado and as a college chaplain. Yet he had never thought of this work as “spiritual direction.” In other words, he had not engaged a group of individuals in spiritual work over a sustained and lengthy period of time as a regular, ongoing enterprise.

At St. Augustine, he was sought by an Episcopal priest who had long been a member of an Anglican religious order. He asked: could Malcolm become his spiritual director? Although he felt untrained and perhaps inadequate, Malcolm said yes. He would give it a try. He and the priest/monk entered into what became a fifteen-year spiritual relationship. Malcolm says: “I had the finest on-the-job training in the world.” Soon several other men and women requested that Malcolm enter into a dialogical pattern of spiritual direction with them. Malcolm says his approach has always been improvisational rather than tightly scripted or adhering to a rigid mode. In a seemingly idle conversation, suddenly a nerve is struck; maybe a childhood experience comes to the fore in a startlingly relevant way; an “elephant in the room” stirs and is identified.

Now Malcolm acts as spiritual director for a dozen men and women. His range has included bishops, both younger and older persons, a Lutheran pastor, a Methodist pastor, gays and straights, mostly Episcopal clergy but also deeply committed lay people. Individual sessions can run to three hours. Malcolm’s approach is to be as open to his directees as they are to him. So the sessions are intimate rather than distanced, impersonal, or bureaucratic. Spiritual direction, as Malcolm practices it, is less a process of crisis management than it is a long, ongoing, patient process of discovery and self-discovery. It is marked by both simplicity and humor. Faith is not perceived as a museum piece but as a living and present force.

In a letter to someone seeking spiritual direction, Malcolm describes his own unusual style of doing spiritual direction. Malcolm writes one of his directees:

I honestly don’t know who would be a good spiritual director for you! My own approach is so out of the ordinary, not formal, built on relationship and dialogue. I’ve simply related to a number of individuals who asked me to “be” that role in their lives. However, I’m not a “member” of a “group of spiritual directors.” God knows who could “be” this for you. (God undoubtedly does, yet that doesn’t help us very much right now.) Take a deep breath, look around (and closely, and pray).

Someone is writing my biography! This is a strange, altogether new experience for me. Requires much emotional and mental digging into my past.

Mark is fine (and, of course, has a new book just out). Diocese of LA is chugging along well. The two new suffragan bishops are splendid. All blessings, Malcolm.14

Malcolm’s style of spiritual direction was indeed that of being—being present to the seeker of God. There was no pretense of technique or getting the words exactly right. As I asked my own narcissistic questions about prayer, God, justice, bad religion, and much more in front of Malcolm, narratives and wisdom flowed from Malcolm’s life experience. It was impossible to be self-absorbed while hearing Malcolm’s staccato laugh or to despair while listening to him read one of his provocative poems. After a year of being in spiritual direction had almost passed, I experienced an epiphany. “Malcolm, you need a biography,” I said. We both pondered the thought. A few days later Malcolm writes the following letter:

Dear Michael: Pursuant to our conversation re: a book you might write, I have some thoughts. I don’t “want” or “need” a biography, which seems pretentious and premature. Nobody (including myself) cares about all the intricate details of my life!

What has my life represented? Its “Rosebud”—its deepest significance—seems found in my somewhat unexplainable passion for justice which found basic expression in my participation in what we call civil rights. I’m also thinking along similar lines as a possible focus of your work and in line with both your skill and your image.

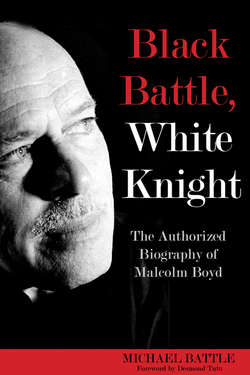

I’m thinking of a book title: “Black Struggle, White Knight.” Obviously this is a suggestion. My point is: I was not “unique” in this. There were many “white knights,” volunteer men and women who sacrificed in different ways to enable a movement. I am not an “exemplar” or “role model.” I was (and am) one of many. All of us, in our small and varied ways, paved the way for the phenomenon of Obama.

I remember often being told by blacks in the movement “Your job is with whites, not blacks.” I disagree because I see this as not being “either/or.” I have always seen it as “both/and.” I believe it is time for a prominent/skilled black figure to write about deep white involvement in the historic and ongoing movement. In beneficial ways this could open up a more meaningful racial dialogue.15