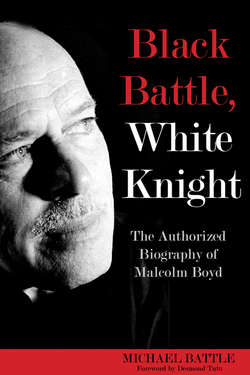

Читать книгу Black Battle, White Knight - Michael Battle - Страница 13

CHAPTER ONE Running with the Horses

ОглавлениеIf you have raced with foot-runners

and they have wearied you,

how will you compete with horses?

(Jeremiah 12:5)

In light of the title of this book, Malcolm’s life reimagines the four horsemen of the Apocalypse described in the Bible. In the book of Revelation, chapter 6, ride the four horsemen of Pestilence, War, Famine, and Death. The image of the four horsemen gives shape to the chapters of this biography. After the glowing accolades of Malcolm already mentioned in the foreword and introduction, why this dark tone and chapter structure to describe Malcolm’s life? Simply put, the four riders of the Apocalypse help me to connect the dots of Malcolm’s deeply textured and nuanced life. Malcolm’s life seems symmetrically organized around the continuing apocalyptic threats that still wreak havoc on planet earth. Before we look at the four horsemen and how they correspond to Malcolm’s life, a short story is in order. The primary imagery and metaphor of the four horsemen invites the reader into the apocalyptic presence that Malcolm often brought to his audience.

The questioner was a girl, about twenty, with somber brown hair, big droopy eyes, and a thin-line quivering mouth. She was sitting, straightbacked and intent, in the Dwight Hall Common Room at Yale University beneath the tapestries and heavy architecture which make the room seem smaller than it is.

She was pleading with Malcolm, who was sipping coffee as the week’s guest sermonizer must at the coffee hour. What she wanted, and what everyone wants out of Malcolm, was an answer—something solid, a bedrock to refer to when everything else is crumbling. She wanted a bright light, a quick conversion, a truth.

She was looking earnestly to Malcolm probably because she had read his “prayer book”—Are You Running with Me, Jesus?—and knew his struggle was hers. She asked the short, almost bullet-shaped priest what were his “absolutes.”

Malcolm’s answer was simple and misleading.“God, I guess, and community, and probably Jesus.” One might think he meant heavenly father, sacred church, and holy son, if one didn’t hear what followed.

“But I can’t believe love and justice are absolutes, although I once did. This morning I read about Orange-burg, South Carolina. The Orangeburg massacre occurred on February 8, 1968, when nine South Carolina Highway Patrol officers fired into a crowd protesting local segregation. Three men were killed and twenty-eight more were injured (mostly shots in their backs). After the massacre, two others were injured by police. And a pregnant woman later had a miscarriage due to being beaten. The Orangeburg massacre predates other major civil rights revolts such as the Kent State shootings and the Jackson State deaths.”

Because of these violent contexts, Malcolm’s jolting candor bars him from handing out easy answers to the hung-up. He can’t talk about heavenly father or sacred church because he doesn’t understand them in terms of “crisis ” or “napalm.” He didn’t even want to climb the Battell pulpit in Yale’s chapel earlier that morning, because he couldn’t see the reason why he should be up there. He’s too impatient to cope with boring liturgy, unheard music, and velvet-laden gowns.

Two weeks earlier in New York, Readers’ Digest, of all groups, sponsored a discussion of “religion in a world of change,” whatever that means, and Malcolm was one of the panelists.

The questioner this time was a Kent-smoker, fiftyish, with no lemon juice in his yellowy-white hair. Frankly troubled, like any normal vestry-man, his normally sedate nervous system was jumpy and he could sit no longer. A kindly woman had asked Yale chaplain William Sloan Coffin, another panelist, what he would tell a young man who wanted to become a minister. Coffin answered by saying he could not tell anyone what to do, he could only ask questions the young man might not have already answered. The Kent-smoker’s normally pink face was reddening. He had to interrupt.

“If you church leaders don’t attempt to lead, then who… ?” This was Malcolm’s cue.

“We’re not leaders, man. How could we be? Readers’ Digest just got us together to talk some things over.”

Malcolm is irony. He is a “leader” of the “alienated,” but he refuses the onus of leadership. He is a priest, but he hasn’t the concrete faith of a Coffin. He is the only campus lecturer who is likely to say “I don’t know” a half-dozen times every night.

“Boyd’s a sensationalist,” says one Yale student. Another adds, “Boyd’s an ass. I just can’t handle an Episcopalian minister who says ‘bitch.’”

Malcolm is masterful in front of an audience, born and trained. When he was concluding his talk in Battell, he had even the easy doubters and cool sophisticates moving to his beat. He uses the shock effect because it keeps the audience with him and because that is often the only way to communicate. He is seldom at one campus for more than two days and never at one university more than twice a year. He must be bluntly honest, because there is no time to cajole and persuade.1 Because of how Malcolm affects his audiences, I perceive Malcolm’s life in the framework of the “Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse.”

The beginning of the book of Revelation tells of a scroll in God’s right hand that is sealed with seven seals. Jesus opens the first four of the seven seals, which summons forth the four beasts that ride on white, red, black, and pale-green horses symbolizing conquest, war, famine, and death, respectively. For some, the interpretation of the Christian apocalyptic vision is for the four horsemen to wreak havoc upon the world as harbingers of the end of the world. Such interpretations are dangerous among those who may not fully understand the complexity of power revealed in this surreal book of Revelation. For example, the influence of this Armageddon theology is reflected in a Federal Bureau of Investigation report that certain individuals have acquired weapons, stored food and clothing, raised funds, procured safe houses, prepared compounds, and recruited converts to their cause, all in preparation for foreign attacks. Many believe in the militia movement in the United States that the Antichrist will attempt to take over the world in the near future. There were over 100 extremist militias that the Southern Poverty Law Center has identified as active in the United States in 2009. In March 2010, one of these militia units, called the Hutaree, had several members arrested for planning an attack on the police.2

So, interpretation of the book of Revelation must be entered into care-fully. Each of the four riders is summoned onto human history by one of the heavenly living creatures. The opening of the first four seals reveal the four horsemen of the Apocalypse. Each one of the four living creatures reveals a horseman, the first three horsemen are summed up by the fourth horsemen, “They were given power over a fourth of the earth to kill by sword, famine and plague, and by the wild beasts of the earth.” But remember, power in heaven is strange, if not seemingly unstable.

Although the four horsemen of the Apocalypse are described in just eight verses of the book of Revelation (chapter 6:1–8), which is the last book in the Bible, they are also eerily foretold in the same chapter and verses of the Hebrew Bible, from Zechariah (6:1–8) in which there are four chariots pulled by variously colored horses, conveying the four spirits of heaven proceeding from God to the world. The four horses also travel in four directions, that is, they affect the whole earth. For Zechariah, the horses appear in the following order, red, black, white, and finally the pale horse. Zechariah’s horses differ from Revelation’s not only in their order but also they do not indicate anything about their characters since they are more like sentries than like agents of destruction or judgment.

In Revelation, the four horsemen appear when the Lamb (Jesus) opens the first four seals of a scroll. A seal was a security measure used when a letter was dispatched from a royal office. Often this seal was made using a signet ring, hence the word signature. Such imagery is fitting for the Revelation of John since the biblical message was often conveyed through epistles or letters. In the strange vision of Revelation, the seals were not just security measures. Such seals meant something much more. John’s Revelation contained all together the following seven seals:3

1 The white horse

2 The red horse

3 The black horse

4 The pale horse

5 The martyrs

6 Anarchy

7 The fanfare of trumpets

As each of the first four seals are opened, a different colored horse and its rider is revealed. And yet, earlier in John’s Revelation (chapter 4) we see God seated on the throne in heaven, but also sovereign over earthly events. A paradox of power occurs as the Lamb ( Jesus) appears in chapter 6 and takes the scroll from God. This is a paradox because how can a lamb be powerful? And yet the Lamb not only snatches the scroll, he also breaks the seals, a privilege only for Kings. To further the paradox, especially as practiced by the less divine, the first horse and rider, white in color, is interpreted as good, representing either Jesus or the church going out, in victory, sharing the gospel. The time, however, eventually came when the church became a persecuting power, mutating to a second rider on a red horse with a sword in his hand. The paradox here is in how the first horse and rider is juxtaposed to the second, who represents a history in which the church turned on its own members. The crime of many who were killed was the “crime” of reading the Bible. For example, in the year 1215 Pope Innocent III issued a law commanding “that they shall be seized for trial and penalties, who engage in the translation of the sacred volumes, or who hold secret conventicles, or who assume the office of preaching without the authority of their superiors; against whom process shall be commenced, without any permission of appeal. ”4 Innocent “declared that as by the old law, the beast touching the holy mount was to be stoned to death, so simple and uneducated men were not to touch the Bible or venture to preach its doctrines.”5

Rather than promoting erroneous interpretations of this important book of the Bible, the key to interpreting Revelation is Jesus. This is Malcolm’s key interpretation as well. Similar to the way the first century had a difficult time interpreting the Messiah as someone meek and mild like Jesus, so do we have complexity in interpreting Revelation, the second coming of Jesus. What is described by the seals is similar to the signs of the end of the age as described by Jesus in Matthew 24. There will be wars, famines, and earthquakes (Matt 24:6–8); persecution (24:9–14); and the heavenly bodies will be shaken (Matt 24:29): “Then the sign of the Son of Man will appear in heaven, and then all the tribes of the earth will mourn” (Matt 24:30). After the opening of the seven seals, the scroll can be read and we will find more detail, but this starts in chapter 8. The seven seals describe tribulation that is largely the result of human foibles (wars, famine, and persecution) but under the control of God. The fact that the seven seals are opened by Christ indicates his sovereignty over the future. Jesus is the Alpha and the Omega, the First and the Last, the Beginning and the End (Rev 22:13); he is sovereign from the beginning to the end of history, and everything in between.

Focus on Jesus in the book of Revelation should prevent militia and extremist groups because John’s vision indicates that these strange occurrences all occurred under the sovereignty of God. I think this is strange; after all, the Lamb is the most powerful one. Even if we do not understand the message of Revelation, the reader is obligated to give assent to God whose strange sovereignty lasts from the start to the finish. The Lamb’s enemies end up defeated and punished while the saints are vindicated and rewarded. The revelation ends with a new heaven and a new earth where there will be no more death, crying, or pain. The vision all along was for a different use of power in which a Lamb sits on the throne of heaven. God’s plan for the future of the world, especially as the apocalyptic vision is progressively revealed, is not to destroy, but to create. This revelation comes with the instructions to record the prophesy so that it can be used to encourage a struggling first–century church. In many ways, Malcolm fits this progressive apocalyptic vision–especially as Malcolm seeks to create rather than destroy.

This detailed review and interpretation of the seven seals is necessary for understanding Malcolm because so much of Malcolm’s public impact was either interpreted as creative or destructive. The verdict seemed to be in the eye of the beholder. Similar to the early church’s apocalyptic literature, how one interprets the end times of an empire often depended upon having power or not. On one hand, if you were invested in the power structures of the empire, of course apocalyptic realities were seen more as a horror movie. On the other hand, if you were marginalized or oppressed (like the early church), apocalyptic realities meant something else entirely. The oppressed longed for the toppling of the empire. For the marginalized and oppressed, the Apocalypse is actually a creative act.

Today, especially in our Western culture, it is difficult to be encouraged by apocalyptic worldviews. Malcolm’s genius in many ways represents the divide between how apocalyptic worldviews seek to encourage societies out of ruts and how modern–day society has a difficult time receiving such worldviews as constructive and creative. Of course, any society struggles with its own end; after all, who can really handle “extra-reality” judging our current reality? Our particular struggle in the Western world comes because we expect an empirical revelation full of complete and technical accuracy. We were the masters of such revelation, but now we are beginning to see Chinese and Indian children out achieving our own. Instead of being insecure, Malcolm is helpful to the Western worldview. Malcolm’s apocalyptic worldview entails judging the world according to extra–wordly or transcendent standards. In other words, instead of seeing others as a threat to our existence, why not simply understand that the world never stays the same?

Malcolm’s mission was in fact one of encouraging the church, but not in ways that she often wanted. Malcolm’s word of God revealed God as one who could transcend all of us and yet sit in a coffee shop and a bar, a God who could love us equally in Sunday morning worship and Friday night laughter. Consequently, Malcolm approaches God’s revelation without too much anxiety about whether he has gotten such revelation precisely correct. His mission is simply to make known that there is indeed a revelation from God.

This revelation often comes across as apocalyptic to those who cannot accept truth and reality as coming beyond self (and even Western culture). Malcolm’s vision is akin to the writer of Revelation who envisions four horsemen galloping through the desert on a horse with no name. But Malcolm accepts the judgments that are coming and tries his best to help us do so as well as he gleans what has been given to him in the poetic imagery of God who transcends us and yet drinks coffee with us.

Though the faith–minded might find comfort in my interpretation of Malcolm’s impact, there is also a challenge to us as well—namely, the imminent side of God (the One who drinks coffee with sinners) is not all there is to God. God is also transcendent. So, although the faith–minded may look for the seven signs of the Apocalypse as taking place in the order in which they appear in Revelation, there is little need to actually follow this order. To understand that God transcends us should actually take the pressure off. Belief in God alerts us to the fact that our interpretations of reality usually carry with them self-fulfilling prophecies that often end us in ditches rather than flourishing places. In other words, God keeps us honest between hope and despair. Malcolm irritates the faithminded just as he does the empirically-minded in that no one can be selfsufficient, really. In addition, for many faith–minded, Malcolm could never be their brother due to their never being able to accept his identity as a white, gay Episcopal priest. Keep in mind that Malcolm’s impact comes through his poetic, apocalyptic literary style that paints a picture of how God’s kingdom accepts a person wherever they are.

When Malcolm prays, “Are you running with me?” he prays to a Jesus who came to fulfill the promise that God made to Abraham that his descendents will be impossible to count. In fact, Malcolm’s message does not bring us a new revelation, but rather places in writing the same message that Jesus brought us, but does so in a wonderful and colorful literary style.