Читать книгу The Man Between - Michael Henry Heim - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеA HAPPY BABEL

Adriana Babeţi: When you arrived at Timişoara, you were sweaty, hungry, and thirsty: your train had come to a standstill on the tracks for two hours, in an open field, under a forty-degree sun. A railway strike. Yet when you stepped out of the train, your face had a smile I couldn’t understand. You explained that sitting opposite you was a young man who bore an unbelievable likeness to yourself, at age seventeen. How would you describe your seventeen-year-old self?

Michael Heim: I was a more or less typical American in that I was extremely naive: I had never been outside the U.S. and knew nothing of the world. It was 1960. I had just finished high school, a public high school in the semi-rural borough of Staten Island, a true anomaly, administratively a part of New York City, but tranquil, provincial even. Imagine, many of the residents had never been to “the city,” as they called Manhattan, which was only a thirty-minute ferry ride away. (I made the bus, ferry, and subway trip to Manhattan every Saturday to take piano and clarinet lessons at the Juilliard School of Music preparatory division.) I felt a little foreign to the place, having come there from California. We had moved because my mother remarried after my father’s early death.

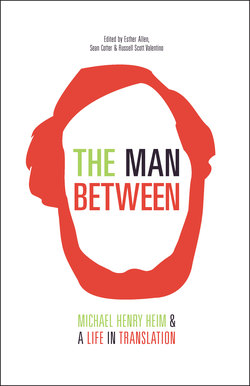

Heim as a toddler.

Adriana Babeţi: Where were you born?

Michael Heim: I was born in Manhattan, as it happened. My father was a soldier, stationed in the south, in Alabama. I was supposed to be born there. But at the last moment my mother got cold feet: she was worried about the conditions in the military hospital and decided to give birth in Manhattan, where her mother was living at the time. Barely a month after I was born, however, we moved to Texas, where my father had been transferred. Then, toward the end of the war, we settled in California, in Hollywood, because my father wrote movie music.

Adriana Babeţi: Who was your father?

Michael Heim: He was, of course, a Heim, Imre (Emery in English, which is what my mother called him) Heim, but he composed under a pseudonym, Hajdu, a common Hungarian surname. My father was Hungarian. It’s possible that Hajdu was his mother’s maiden name; it’s possible he used Hajdu to highlight his Hungarian origins, Heim being of course a German—or, in my family’s case, Austrian—name. My father was born in Budapest, as were his parents. My grandfather’s name was Lajos, my grandmother’s Sárolta. Unfortunately, I know nothing definite about my paternal great-grandparents except for a hint from my grandmother that one of them was a Gypsy. Most Americans of my generation and earlier had scant knowledge of their forebears. Nor did my mother and her mother, both of whom were born in the U.S., take much interest in their ancestry. Our family lore is limited to the following: my grandmother was the last of sixteen children and the only one born in America. The rest came from Kovno in what was then the Pale of Settlement. My mother was Jewish, my father Catholic.

Heim, age 6.

Adriana Babeţi: Could you retrace your father’s footsteps and put his biography together? What do you know? What do you remember?

Michael Heim: I remember listening to what I later learned was classical music, and I remember that the first piece of music to stick in my mind was Stravinsky’s Petrushka. I couldn’t have been more than three, but when I heard it again much later I perked up immediately. Superimposed on the music is the image of my father. I have photographs and an elegant charcoal portrait, so I know I resemble him closely. So much so that one day, a friend of mine, seeing a picture of my father as a soldier, asked me how I came to be wearing a uniform, since he knew I’d never served in the army. When my grandmother in Budapest (my mother and I always referred to her as “Grandma-in-Budapest”) saw me for the first time, she cried and cried. She said it wasn’t her grandson visiting; it was her son. My father was born in Budapest in 1908 and studied piano at the Royal Conservatory with Bartók, but—on my grandmother’s insistence—also apprenticed to a master baker in Vienna. Baking was the family trade. My grandparents ran four pastry shops in Budapest.

Adriana Babeţi: What were Viennese baking schools like?

Michael Heim: Very rigorous, I imagine. But I knew nothing of Viennese or Hungarian cuisine. I didn’t eat my first palacsinta until I visited my grandmother. By the time my father left Europe, he had gained a reputation as a composer of popular music, the Irving Berlin of Budapest, my mother used to boast. One of his specialties was reworked Gypsy melodies. Once in a Budapest restaurant, the musicians learned I was Hajdu’s son and immediately struck up one of his hits. But he was also one of Hungary’s best-known film composers. A few years ago a friend brought me a videotape of a Hungarian film from the thirties scored by my father. It was very much of its time and quite good, actually. I had been told he also provided the score for the classic Czech film, Ecstasy—classic, because it purports to be the first film to show a woman in the nude, the famous Austrian beauty Hedy Lamarr, running through the woods. Given my later fascination with things Czech, I was naturally intrigued but also a bit skeptical. How could I have missed a reference to my father? But five years ago I managed to view the film and everything fell into place. It features a twenty-minute scene in which the hero visits a Gypsy tavern. Aha, I thought, so that’s why my father had been called in. The on-screen credit went to the man responsible for the rest of the score. My father would also do some ghostwriting later in Hollywood, where he was getting a new start and completely unknown.

Adriana Babeţi: When did your father go to America?

Michael Heim: In 1939, for the New York World’s Fair. As a pastry chef in the employ of Gundel, then, as now, one of the most sought-after restaurants in Budapest, one my grandparents provided pastries for. As it happened, Gundel handled the food concessions at the Hungarian pavilion and needed skilled pastry chefs. The war had broken out in Europe, and America was a safe haven, but it was very hard to get a visa. Not for my father, though. He went as a pastry chef, not a refugee.

Adriana Babeţi: Would he have left Hungary if it hadn’t been for the Fair?

Michael Heim: As I say, it would have been all but impossible. He met my mother in 1939 or 1940 through friends who recommended him as a piano teacher. She had taken piano lessons as a child, and her friends knew my father was looking for work. That’s how they met. My mother was five years younger than he was. Her family was relatively well off. They had had a lumber business in the old country. They were Ashkenazy Jews, but completely assimilated.

Adriana Babeţi: What was your mother like?

Michael Heim: Her name was Blanche. She was beautiful and intelligent. But like many middle-class American women at the time, she made less of her life than she could have. She finished college during the Depression and longed to study English literature. She was the perfect anglophile: she enjoyed English tea, English novels, the English lifestyle. But she had to do what she could in those hard times, and she went into marketing. More precisely, copywriting with a little modeling of hats on the side. It wasn’t particularly thrilling, but it enabled her to make her own way. Then she got married. At that time when a woman of a certain means married, she gave up going to work. My mother read five or six novels a week; she cooked, gardened, crocheted, and did charitable work. (My wife Priscilla characterized her as “comfortingly normal.”) She played tennis regularly, and we occasionally played together. She had been Westchester County Women’s Junior Champion for a year, and I have a feeling she and my father, also an avid player, bonded more over tennis than piano lessons. Of course she also raised a child, me. She was a good mother, very hands-off. She simply expected me to do well in school and so never made anything of it. Some assumed I would follow in my father’s footsteps and become a musician, but soon my true passion came to the fore: practicing scales on the piano at the age of eight or nine, I would prop a novel on the stand and read away.

By the time my parents married, Pearl Harbor had brought us into the war. My father immediately joined the army and became a proud American citizen. When I was born, they named me Michael, not because there was anyone on either side of the family by that name but because in my father’s mind Mike was the quintessential American name. He served in the entertainment corps, playing for the troops and composing battalion marching songs and the like. But then a freak accident occurred—we never found out what it was exactly—and in 1946 he died of cancer from the consequences. I long puzzled over what connection there could be between physical trauma and the growth of abnormal cells in the body until I found an answer in Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilyich, where death comes about in an analogous manner.

In 1966 I was drafted to fight in Vietnam. I was against the war, but not being a Quaker I was ineligible for conscientious objector status. If it had to be, it had to be. But when the draft board went over my background, they discovered I was the sole surviving son of a soldier who had died in the service of his country. Drafting me was illegal. They immediately kicked me out of the office, cursing me for wasting their time.

Adriana Babeţi: What kind of contact did you have with your father’s parents in Budapest?

Michael Heim: My father had invited them to come to California, but they refused, claiming old age. When my father died, my mother determined to visit them. But by the time she’d gathered the necessary papers, it was too late: the Cold War was in full swing, and the Communists had taken over. My grandparents experienced difficulties under the Communist regime. They belonged to the bourgeoisie: they owned an apartment building and a building that was bombed out during the war, and they had a private business. Everything was confiscated. My grandfather died some time in the fifties, but I did get to know my grandmother when, in 1962, I went to Europe for the first time.

I found her wonderfully engaging. She had even managed to maintain a sense of humor throughout the disasters of her life: the loss of her son, the loss of her husband (by all accounts a jolly old soul), the loss of her very living space. She was forced to share her apartment first with a family of strangers, then with two, and was eventually moved into an old age home. We would send her monthly packages. During our visit together she brought out a leather jacket of mine we had sent when I was ten. She was so shrunken she could still wear it. My mother and I would write to her in English, and as a child I had no idea she didn’t know the language. Only after getting to know her in person did I learn that she had paid to have our letters—and her own—translated. But by then I was studying German, the second language of all educated Hungarians of her generation, and we had been corresponding in German for some time. And if she wept when she first laid eyes on me, it was not merely because I was the spitting image of her son but also because she couldn’t believe I’d actually learned German: she assumed that we, too, had hired a translator. She and I talked non-stop for a week, then maintained a regular correspondence until her death in 1965. I’ve kept a bundle of moving letters from her. The salutation was inevitably “Mein heissgeliebtes Mikykind” (My Dearly Beloved Mickey).

At the time I was passionately interested in Chinese philosophy, which to my mind held the key to a conundrum I later discovered has plagued many an adolescent, namely, whether man is born good, evil, or a tabula rasa. I hoped the answer would guide me through life. As a Columbia undergraduate I accordingly majored in Oriental Civilization (which encompassed the history, philosophy, and literature of China, Japan, India, and Islam) and studied Chinese for two years. But I was crushed when I learned that as an American I would not be permitted to travel to “Red China” to study at the source. I took my advisor’s advice and started Russian. “You will never want for employment,” he told me, “if you have the two major languages of the Cold War.” Since my advisor, F. D. Reeve, a prominent Russianist and poet, also happened to be the father of Christopher Reeve, the most recent Superman, I like to say it was Superman’s father who put me on to Russian.

In the end, I double-majored in Oriental Civilization and Russian Language and Literature, the latter taking over in the guise of Slavic Languages and Literatures when I went on to graduate school at Harvard. Although Grandma-in-Budapest accepted my original Chinese orientation with equanimity, I can imagine how thrilled she would have been to know that I eventually learned Hungarian (“Don’t forget you are Hungarian” she kept telling me) and translated some of the finest contemporary Hungarian writers including Péter Esterházy, scion of the noble Esterházy line.

•

Adriana Babeţi: If I remember correctly, the first foreign language you learned in school was French. Why?

Michael Heim: Because it was the international language, the language of a great culture. Then came German, to write to my aunt and grandmother in Vienna, who sent me a birthday present every year on behalf of my Hungarian grandparents, whom the state kept from sending anything.

Adriana Babeţi: Did they ever send anything special?

Michael Heim: Yes, more than once, and I still have some things. A leather bag, for one, and something even more unusual, a camera. It was a very complicated device for me at the time, and it came with a German manual that I couldn’t read. I was eleven or twelve, and hadn’t begun any foreign language at all. The gift irritated me. What was I supposed to do? It was the first time I encountered, as an idea in itself, a foreign language. I started to take pictures. I tried to do a lot of different things, most of which did not work because there was no one to read the manual for me. I decided to become a photographer; I even set up a darkroom. I took it very seriously. I probably could have made a career out of it. When I went to Budapest for the first time, I wondered what I would have become if I had been born there, under communism. It’s hard to say. Maybe a piano teacher, or a photographer, because those fields weren’t political.

Adriana Babeţi: You said you have your father’s gift for music.

Michael Heim: When I was eight, I took piano lessons from a magnificent teacher. Later, I went to Julliard, the famous music school. I took lessons every week: piano, flute, and clarinet. Plus theory. I played in a wind quartet.

Adriana Babeţi: And yet, you didn’t go into music or photography. Why did you choose literature?

Michael Heim: I didn’t follow through with a music career because it was clear to me that I didn’t have enough talent. Music was very demanding. Next I wanted to become an architect, because we lived in an apartment and I dreamed of buying or building a house. I loved to look at plans and architecture magazines. They fascinated me. But I couldn’t draw. So I was left with literature, which was how I spent all my time, anyway. I read and read, just like my mother. Even when I took an hour break from practicing the piano, I read.

Adriana Babeţi: What did you read?

Michael Heim: Novels, classics, English literature especially. But also adventure stories. Everything. I read even while I was doing my arpeggios. But I didn’t want to specialize in literature, I just wanted to read. When I went to college, I purposely did not choose to study literature. I didn’t want to ruin the pleasure of reading, to turn a pleasure into a job. It was an interesting field, but too dry.

Adriana Babeţi: Where did you study?

Michael Heim: My first four years of college were at Columbia, in New York. I stayed in New York to continue at Julliard, no other reason. At Columbia, I became interested in Asian studies. Then I moved to Harvard, where I started to study linguistics. That was interesting, but also dry. I thought I would get bored. And I was still reading as much as I could. In the end, after my master’s, I surrendered: I decided to dedicate myself to literature. In 1970, I finished my doctorate in Slavics. At Harvard, I studied with Roman Jakobson, and his wife suggested I focus on literature. She was my Czech professor.

Heim, 1974.

•

Daciana Branea: You are an excellent storyteller. Did you ever think of writing, yourself?

Michael Heim: I’m often asked that question. My answer is simple: There are so many wonderful books that need to be translated, and this is what I know how to do best—I’m not being modest, just honest. As long as there are untranslated books in the world, I know that this is where my duty lies. I have some ideas I could write about if I ever started to, but I prefer to work on those books that I already know can change people’s lives. I still have some time.

Adriana Babeţi: Today, when you are more than fifty-five-years old, do you still believe in literature? Do you believe it can change anything, to repeat a well-known question?

Michael Heim: Do you mean now?

Adriana Babeţi: Yes, now. Can literature make a difference?

Michael Heim: Oh, yes, it can do a great deal. I believe literature is enormously important today. But I didn’t at the time. I just loved it. I do believe in its enormous importance, precisely because it is ignored: it is not a practical field. We could say it’s a lie. But a lie that can go far, very far: all the way to a truth. Not Truth, but a truth that we’ve forgotten. A truth somewhere beyond us, not within, but one that may become part of us if we accept the idea that outside of ourselves are worlds and people who feel in different ways.

Adriana Babeţi: Who needs literature today? Even here, in Romania, where people read a lot before ’89 (for reasons we all know), belletrist literature seems to be in retreat.

Michael Heim: It’s true, things here were different than in America. But your situation was artificial. You read a lot because you had no choice. You read the best literature from the rest of the world, just because it was so difficult to get to that world or even talk about it. It was a kind of sublimated revolt against the political order. Once other forms of action appeared, once people had a chance to make a real choice, they began to forget literature. In the West, this decline has been going on for more than a hundred years. And yet literature still exists, because there will always be a small group of people who cannot live without it, people for whom it still means something. I am bothered by the fact that, in American society, it almost seems someone is making a special effort to keep people from reading literature. It’s a kind of false democracy. We’re afraid literature is too elitist, too difficult for most people. Of course, everyone in America has heard of Shakespeare. But far fewer have heard of Goethe, Dante, Flaubert. And this is true even in the academic world. It means that people haven’t been given the chance to learn that these great writers exist. Maybe some know that Cervantes is a great Spanish writer, but they probably heard about him from a grammar exercise in Spanish, a language many of us study.

Adriana Babeţi: Is it possible to live without Don Quixote?

Michael Heim: It’s possible, of course it’s possible. But what kind of life is it? Perfectly quiet and flat. You can live without Don Quixote, especially if you don’t even know it exists. What upsets me is the fact that there are thousands and thousands of people in the United States who are deprived of Don Quixote. Or The Divine Comedy. Or The Human Comedy. They don’t know these things exist, simply put. They don’t know what literature there is to read. I have students at the university who have never read a novel.

Adriana Babeţi: How is that possible? Don’t high schools teach world literature? Or any literature?

Michael Heim: They teach what is called “English,” and which for most means spelling and very practical exercises: how to write an essay with an introduction, conclusion, etc. The teachers don’t even know about literature, because they were only born thirty or forty years ago. They don’t even know what they are missing.

Adriana Babeţi: But what about those who study literature at college?

Michael Heim: That is a very small group, as I said. Of course, there will always be such a group. Parents read literature, children see their parents read literature, or they have a professor to convert them, to send them to the libraries—the many, immense public libraries in America—and make them read novels. The number of passionate readers remains tragically small. What can we do? As a professor, I for one know what I have to do. How can I make students fall in love with literature? Instead of talking about sophisticated theories, I get them going with a simple question, such as: why did you read this book, what can a classic work say to you? What does literature mean to you? How can it change your life?

Adriana Babeţi: Did a book change yours?

Michael Heim: I’d just as soon say no particular book changed my life, but books did. What would my life be like without books? Absolutely bland and uninteresting. I can’t say this is true for everyone. Just that many, many people in the United States live flavorless lives, and they don’t even know it. Maybe they sense something is missing, but they don’t know what. They watch television, work, stay home, see a movie, most often they simply lead empty lives. Many people believe they can fill their lives by shopping. This is truly a disease for us. For some, going to the mall is the highlight of their week. I don’t believe that literature is for everyone, but it can offer everyone a more meaningful existence. Still, people don’t know this, because we didn’t tell them when they were children. The French novelist Daniel Pennac wrote a fantastic book about reading and the way literature should be taught. It’s called Comme un roman. Pennac holds that every child, every person has an almost physical need for stories. The stories that children watch on TV are colorless, repetitive, and stereotypical. Unsatisfying. All it takes is the plot of one good novel, or reading a fragment aloud, to win an entire class of children over to literature.

Heim and his granddaughter Jenny, 1995.

Adriana Babeţi: Do you have any children?

Michael Heim: I have three stepchildren, my wife’s children. Twin girls and a boy. I even have grandchildren. Seven. I am a grandfather already. We are a large, mixed family, in every sense. For example, one of the twins is married to a Chinese man who grew up in Thailand. Except for the boy, I haven’t been able to attract any of them to literature. My wife has a principle that I share: we stand alongside our children, we don’t tell them what to do.

Cornel Ungureanu: We’ve been pleasantly surprised by your calmness and serenity. Is there anything that upsets you?

Michael Heim: I am worried by the enormous amounts of garbage we produce. Every day, when I walk to the university—not always a pleasant walk, but even so, I’ve done it for seven or eight years—I collect empty bottles and cans in large plastic bags. I take them home to some Mexican workers, and it’s probably enough material for them make a living by recycling. I collect 60 or 70 every day, so I have probably helped recycle millions of bottles and cans. But I don’t feel any more optimistic for doing it.

Adriana Babeţi: You wrote me once about books you’ve lost while doing this. Which ones? Tell us about the lost books, because what you said sounded almost supernatural. We couldn’t understand what garbage you were carrying, what bags of scrap metal you collected . . .

Michael Heim: It’s ridiculous. There’s so much waste in America . . . If you’ve never been there, you can’t imagine it. There are vending machines every hundred meters where you can buy juice or mineral water. They are restocked every three hours. No one packs a lunch. All the restaurants sell food in plastic containers, which are then thrown away. Mounds of cans are thrown into plastic garbage bags that, in turn, are thrown away. I read somewhere that if we didn’t use plastic bags, we would save six million barrels of oil per day. And you can’t do anything about it, because people refuse to think. In fact, you don’t need any of it. You can make a sandwich and take it to work in a box that will last you forty years.

Adriana Babeţi: When we were in kindergarten, we had little metal lunchboxes . . .

Michael Heim: Made of sheet metal, yes, that was the way to do it.

Daciana Branea: You’ve been reading too much Hrabal!

Michael Heim: You may be right.

Adriana Babeţi: Or Klíma, Love and Garbage. Have you read Love and Garbage? It’s a book about the author’s time as a garbage collector.

Michael Heim: You asked how I lose my books. On my way to school, I study foreign languages. I did this with Romanian. It’s not part of my research, so I study while I walk. But when I read while I’m picking up garbage, sometimes I put my book in the trash.

Adriana Babeţi: You wrote once that, perhaps at the same moment you were writing me, the lost book was being recycled.

Daciana Branea: How long ago did you lose your Romanian book?

Michael Heim: Not long. I got another copy, but I had to promise I wouldn’t take it out of the house. I didn’t, and so I never finished it.

Ioana Copil-Popovici: Michael, do you have any other obsessions besides recycling?

Michael Heim: Yes, I do. What I’m about to say might make you think I’m a little odd. I’ve noticed that, in the last twenty, thirty years—I’ve been teaching at UCLA almost three decades—people have become obsessed with photocopies. I remember when I was in college and I bought a book from the bookstore, I would feel, subconsciously, that owning the book was as good as reading it. Obviously that’s not true, but I kept the book on my shelf and I could open it whenever I wanted or needed to. Photocopying today creates the same sensation, but much worse: when you make a copy, you feel you know that book. In Germany I once saw a sticker over a Xerox machine that said: “Kopiert is nicht kapiert,” that is, “copying is not understanding.” For us, the problem has another, more pernicious side: in college, rather than have the students buy books, many professors use photocopied anthologies. Let’s say you are teaching a course on the Russian novel. You make a course pack that includes the ten novels you will cover. It seems like a good idea, because the students will have the material, and it’s cheaper than buying six or seven books. But in my opinion, it’s very dangerous. In the first place, the students will never buy those books. This means they will never have those books on their bookshelves. Even if they don’t read all that many stories by Chekhov or Pushkin in the class, when they have the books on their shelf, they can always come back to them, loan them to their friends . . .

Ioana Copil-Popovici: But books, at least for us at this moment, have become too expensive for students to use.

Michael Heim: That may be. When we talk about Central Europe, we have to put the question differently. We all know there were no Xerox machines under the totalitarian regimes. Because, in general, copy machines were considered subversive: you could make hundreds of copies of a manifesto, pass them out, and disappear. So Xerox machines were few and well guarded. (In 1980 I did a summer course at the College of Letters in Moscow. The sole copy machine was kept under lock and key.) So you are going through a real Xeroxing euphoria, when you can make copies of anything at no cost. You are in fact in the same situation we are, maybe it’s even more serious for you, since here the copy machine is a novelty. But we tell ourselves the same thing: students don’t have money for books, because they cost a lot for us, too. Books are not any more expensive than they were, relatively speaking, in my time. But think how much money your generation spends, for example, on cassettes, CDs—goodness, on batteries! Why don’t you spend it on books, if you’re a student? A student reads books. That’s his job. Maybe I’m just old-fashioned, and the truth is that today’s students don’t read originals, only copies. Still, I believe that something is lost if they never own these books. When you are done with a course pack, you throw it away. It is not a beautiful thing, something you want to keep. In a way, course packs feel like ID cards, documents, bureaucracy.

•

Marius Lazurca: If you don’t mind, I’d like to ask you a more personal question. You said once, before we started recording, that Dostoyevsky appeared in your life in a certain moment, that he made an impression in this moment, but later you moved away from his vision of the world, toward a different cultural sphere. Would it be correct to say you traveled from a period of belief toward one of atheism?

Michael Heim: No, I wouldn’t say that.

Marius Lazurca: Or, to put it another way, from a period of unknowing piety to lucid atheism?

Michael Heim: Not at all. I would love to answer this question, I don’t mind at all. When I was 16 or 17, I was searching, like all young people, I wasn’t any different, but maybe I thought I was, at the time. This is why I like to teach Dostoyevsky to young people. I know that this author may become very important for them, that they need a point of reference for their ideas, and Dostoyevsky seems like a good choice. I enjoy his books to this day, but I do so from my students’ perspective. Chekhov never mentions God, but he seems to show a world in which imagining God is possible. It is much subtler, a veiled way of speaking about the divine, an approach that later became stimulating for me, as much intellectually as spiritually. I found something like it in works by Central European authors. They don’t try to fix my problems, don’t offer solutions or try to make me their disciple, but instead, their texts suggest new ways to think about the ideas that interest me, ways I would have not discovered on my own. This is why I believe that literature plays an extremely important role for those drawn to study the spiritual side of existence. For me, as a twentieth-century person, Havel’s words are extremely important—perhaps even more important than Dostoyevsky’s theology. We are part of a world in which we, the human race, are not alone, but connected to a power above us, which we can call whatever we like, but which calls on us to take responsibility for our deeds. If we don’t think reality is above us, but within us, then perhaps there is no real reason—this is going to sound like Dostoyevsky—why we shouldn’t kill each other. Responsibility for our freedom—words that again sound like Dostoyevsky, but I think that Havel’s way of putting it is more appropriate for the twentieth century—comes from the sense that we are not the sole or supreme beings in this world.

•

Cornel Ungureanu: There is a great Hungarian author who wrote a Cultural History of Human Stupidity. Have you read it?

Michael Heim: No, unfortunately.

Cornel Ungureanu: I’m wondering what signs of stupidity you see in the world . . .

Michael Heim: I wouldn’t want to list one stupid thing or another, but you asked before what bothers me. In general—and I’d like to write about this sometime—it bothers me that people rush about without thinking, especially without thinking ahead. As a joke, I’d say that this is our contribution to the world, our Californian or American contribution. California is a good example: it only rains in two or three months out of the year, so when you leave home in the morning, you don’t have to wonder whether you need to take your umbrella with you, or if you will be able to have your picnic. You don’t have to think ahead, and from this, of course, many things follow. Almost all the stores are open non-stop—this is capitalism: you believe that if you stay open an hour later, you can make another dollar. But it also encourages people not to think, but to act impulsively, instinctively. We lower ourselves and reduce our lives through our refusal to think. I’m not saying you have to be serious, or even rational, all the time—I don’t want to give that impression—but the fact that we neglect cause and effect just because it’s simpler to do so . . . American capitalism profits greatly from this commodity. Thousands of things get thrown away . . . Someone put it well: we are not just a consumer society but a throwaway society. If you throw a bottle away, you don’t have to remember to take it to the store to refill it. That’s simpler. This means, on the other hand, that billions of these bottles are lost every year. This is just one example, but it shows how people waste their lives.

Sorin Tomuţa: I’ve heard the same thing about Germany.

Michael Heim: I wouldn’t believe it. Germans are, in fact, much better off than we are, as least as far as recycling goes.

Sorin Tomuţa: People don’t have to think and are encouraged to avoid doing so.

Michael Heim: Yes, they find it convenient. We Americans export this idea and the whole world welcomes it with open arms. Even if, on the one hand, it is a kind of American cultural imperialism, fashionably called “globalization,” on the other hand, it’s nothing we force on people. Take music, for example. I read somewhere that all types of rock have the same rhythm: the heartbeat. The music is meant to hypnotize you, in a way, keeping you from thinking. People who walk down the street listening to rock music on Walkmans look like they’ve been brainwashed. But this is just what they want: a type of music that doesn’t tax their brains. I don’t know what can be done about this, maybe we can try to show people that there are more useful things than short-circuiting their brains. Things that could help them find life more interesting. I don’t think it’s natural for people to do nothing, yet people do so little. I am sure you’ve read that in the United States, people spend on average six to eight hours per day in front of the television.

Cornel Ungureanu: What do you think of Clinton?

Daciana Branea: We were wondering about your politics . . .

Dorian Branea: Are you a Republican?

Michael Heim: No, Democrat.

Cornel Ungureanu: We only asked you that as a goad.

Michael Heim: I liked him at first, and I’ve tried to stay true to my first impressions. Yet, Clinton has made so many mistakes. And now, this scandal, so ridiculous . . . A friend in Washington says that his real problem is that he’s provincial and has never been able to shake it off. Bill Clinton comes from Arkansas and still has not learned that, if you want to do great things, you can’t allow yourself to get tripped up with small things. His sexual issues are a kind of small thing.

Sorin Tomuţa: It’s interesting that this Sexgate incited such a huge political storm. There are conspiracy theories . . .

Michael Heim: There’s no conspiracy, it’s just a small-time provincial who took advantage of his circumstances. This caused a ridiculous and embarrassing situation for everyone. We keep seeing how the European press makes fun of Americans for being so naïve. But in America, on all the call-in shows, people protested the nonstop coverage. There are much more serious and urgent things to talk about. And, in the end, the pressure of public opinion brought the scandal to an end. I was proud to see it. Up to now, I’ve been saying ugly things about Americans, but I have to admit that I was proud when this situation was cleared up. It is interesting that the scandal gave rise to a large number of political jokes, a genre I associate more with Communist Europe than America. For example, a poll was taken of all American women, asking if they would sleep with President Clinton. Twenty-five percent said no, forty percent said yes, and the rest: “Even if you paid me, I’d never do that again.”

•

Adriana Babeţi: How did you come to study the languages of Central Europe?

Michael Heim: I was still interested in Russian and I wanted to visit Europe. It was difficult—now everyone travels everywhere, it’s normal, but then people didn’t have so much money. Furthermore, I had only just turned eighteen, and my family wouldn’t let me go by myself. For me, going to Europe in a young people’s tour group was degrading, I refused. I tried to preserve my independence, but I couldn’t make it work, so I split the difference. At the time—1962, when I was nineteen—the first student trips to the Soviet Union were being organized. Before then, it was impossible, you couldn’t go. So there’s the solution. A trip to the Soviet Union was still adventurous. Even dangerous. I showed I was no coward. But to prepare, I had to study Russian. So Superman’s father, my adolescent pride, and last but not least, Dostoyevsky drove me toward Russian. Then there was another story, somewhat . . .

Adriana Babeţi: Romantic?

Michael Heim: That, too, but I was thinking of something else. In Leningrad, I went into a large bookstore for Eastern Bloc countries, a so-called “Friendship Bookstore.” I wanted to buy some German books, since they were cheaper there. I was thinking I’d buy Goethe, Schiller, maybe Brecht. But I found a Chinese salesperson. I realized I could buy books in Chinese, too. I began to copy the book titles down in a notebook. At the time, I knew about two thousand Chinese ideograms, not enough even to read the titles, so I planned to copy them down and look them up later. When the Chinese clerk saw me, she was shocked. For two reasons: because I was an American, of course, and also because it was the first time that she had ever seen someone write left-handed, and in Chinese, no less! And the first time she had seen a ballpoint pen! This was ’62. It was too much for her, so she came over and spoke to me in Russian. Her Russian was even worse than mine. I responded in Chinese and she told me—today, I can’t believe I understood, but then I did—she told me the story of her life, married to a Russian who beat her, and other things. She wanted to go back to China. We met again the next day and she gave me some of her books, and I gave her my pen—a Parker—and left right away. She was scared to be seen with a foreigner. I knew I would not be able to go to China; it was impossible for an American to visit Red China. I was in Russia and told myself that I would never see China. But I could come back to Russia. It would be difficult, but possible. So I decided to major in Slavics.

Marius Lazurca: So, you gave up on China because of a pen?

Michael Heim: Not the pen, but the Chinese woman. Yes, we could say that was the turning point.

Adriana Babeţi: And then?

Michael Heim: I went back to the United States and continued to study Russian. So I had a double major: Oriental Studies and Russian Language and Literature.

Daciana Branea: Did you ever go back to Russia?

Michael Heim: I’ve been back a few times, but only on short visits. I was in Russia in 1970, while I was writing my dissertation.

Daciana Branea: What was your dissertation topic?

Michael Heim: Eighteenth-century Russian literature, and more precisely, the first translators of French and German into Russian. Trediakovsky, Sumarokov, Lomonosov. Lomonosov is wonderful, a genius. Trediakovsky and Sumarokov are important in Russian literary history, but that’s all. I compared their translations and discussed the role of translation in the development of literary Russian. I told my dissertation chair . . .

Daciana Branea: Was he Russian?

Michael Heim: Yes, most of our professors were Russian. But he had left Russia during the Revolution, when he was eleven or twelve, and grown up in Germany, so he was more German than Russian. I translated his history of Russian literature from German into English. About my dissertation, he said to me, “It’s an interesting subject that I know nothing about. See what you can do. You have two years.” I did what I could.

One day while I was working, I answered the phone and heard a man’s voice: “Mike?” Who could it be? I thought it was my uncle. So I answered, “Hi, Uncle Leonard!” “I’m not your uncle,” the voice said indignantly. “Then why did you call me Mike?” I asked, also annoyed. The conversation continued anyway. The man wanted me to go to the Soviet Union, East Berlin, and Prague as the interpreter for a group of American sound engineers. Three weeks. I wouldn’t make any money, but I wouldn’t have to pay for anything while I was there. I said no, since I was busy with my dissertation. Then I thought I could speed up my research before leaving and be okay missing three weeks. It turned out that the man was the head of an organization named, strangely, the Citizen Exchange Corps, a group that arranged trips to the Soviet Union and meetings with local people. It was very political. Typical 1970s. What was the big danger? Nuclear war. This group thought that if enough Americans came to know enough Russians, no one would ever launch a bomb. At the organization’s office, a few hours before departure, I saw a rare object: the second half of the Leningrad phone book. For years and years, it had been impossible to find a phone book for any Soviet city.

Daciana Branea: Why just the second half?

Michael Heim: I don’t know, but I needed letter Ю), the second to last letter in the Cyrillic alphabet. Because the best scholar of Russian translation history lived in Leningrad, a man named Etkind. So I wrote his number down, and the first thing I did when I reached Leningrad was to prepare what I had to say, in the best Russian I could—since I didn’t want my accent to reveal that I was a foreigner. I called, he answered, I said what I had to say, as clearly and practically as I could: who I was and what I wanted. He invited me to his house right away, we talked for three hours. I explained what I had done up to then, he showed me what was and wasn’t good in my work and recommended a bibliography. These were the three most important hours in my academic life. I returned to the Soviet Union in 1980 and 1981, for three or four weeks. In 1984, I took 60 American students. It was awful. On the first day, one of the students came to me and said, “I have to tell you something very important. Everyone in my family has died of cancer, and I think I have it, too.” He was very upset, he had never travelled abroad, or anywhere, and he was sure he had to see an American doctor. I took him to the embassy and he came back with an aspirin. He was perfectly healthy.

Adriana Babeţi: And how did you come to Central Europe?

Michael Heim: As I’ve already said, when I finished college—this was 1964—I decided to study linguistics; I had studied Russian, Chinese, German, and French. I also spoke Spanish, because I had worked as a guide while in college, to make a little money, and there were many tourists from Latin America. They needed people to accompany the tourist groups, so I had a good reason to learn the language quickly and speak it fluently.

Daciana Branea: How quickly can you learn a foreign language?

Michael Heim: Spanish was not too hard; you’ll remember what they used to say about Spanish. We looked down on it. As you know, Spanish has many dialects. Foreigners learn a standard version that, in fact, does not exist. You had to speak the same language with people from Cuba or Puerto Rico, and you didn’t understand one iota of what they said. They understood us but could not understand why we didn’t understand them. But Spanish became important for another reason: my Hispanic Literature professor would become the most important translator of Latin American literature.

Daciana Branea: Who?

Michael Heim: His name is Gregory Rabassa. He translated One Hundred Years of Solitude, all of García Márquez’s novels. He translated Jorge Amado, and another six great writers who . . .

Daciana Branea: Who translated Borges?

Michael Heim: Not him. The American translations of Borges are very problematic. All of his work has been translated, of course, except for the essays, which a friend of mine is working on at this moment. But Borges, who chose his own translators (and spoke perfect English), didn’t start off with the right people and let himself be led astray by under-prepared translators. One of them—an impostor—called on Borges once, just so he could later claim they were friends.

Daciana Branea: How have American perceptions of foreign languages changed over time?

Michael Heim: Not at all. Or yes, actually, now we think no one needs any foreign languages . . .

Daciana Branea: Except English.

Michael Heim: Americans think everyone in the world should know English. In California, if you want to talk with the housekeeper or gardener, maybe you should know five words in Spanish. No more than five. You can buy special dictionaries: Housekeeper Spanish, Gardener Spanish.

Daciana Branea: Is this politically correct?

Michael Heim: No, but neither are the people who make them.

Adriana Babeţi: And still: Central Europe?

Michael Heim: I began to study linguistics in graduate school because I had learned such different languages, and I liked theory. The same thing happened with music: I was a musician, I liked to play the piano and to study music theory. But after the first week of my linguistics career, I realized I had made a mistake. In the second week, you could still drop a course and add a different one. When people ask why I went to the Slavics department, I laugh and tell them, because it was on the third floor. The French department was on the second. French was—and still is—the foreign language I speak best. I asked for information about their program, but they didn’t give me a second glance, because they already had too many students. The library was on the first floor, Slavic languages the third, and the fourth was German.

Adriana Babeţi: But you never made it to the fourth.

Michael Heim: No, because the secretary on the third was very . . .

Adriana Babeţi: Reserved?

Michael Heim: Worse, blasé. She said something like, “If you’re good enough for us, we’ll know.” So I ended up there. I had majored in Russian, at least on paper, and even if Oriental Studies had been my real specialty, I had worked a lot on Russian. But, back to Central Europe. In the Slavics department you studied Russian literature plus an East European one. If you specialized in linguistics, you studied Russian and two other languages. Russian is an Eastern Slavic language, and the other two had to be Western Slavic (Polish or Czech) and Southern Slavic (Bulgarian or Serbo-Croatian).

Daciana Branea: Did this seem like a more comfortable choice than literature?

Michael Heim: As I’ve said, I didn’t want to study literature because I liked it too much. The same reason I didn’t study music. I thought literature meant so much to me that it would be a mistake to approach it professionally. Work is one thing, affinity another.

Daciana Branea: Maybe we should change our specialties, too . . .

Michael Heim: You shouldn’t make something you like into your job, or so I thought. I studied Slavic linguistics, which was completely different from general linguistics. I could do a little literature, too. I chose Czech. Why? Two reasons. I had heard the Czech professor was very good—when I tell you who it was, you’ll understand. Then, I remembered something my mother had told me about Czechs. When my father was a Hollywood composer, there was a kind of Central European mafia: they wrote the music, directed the films, they did everything. There were many in the business, but you don’t hear about most of them. For example, my father, a newcomer, wrote music for films without ever receiving credit. This happened with everyone starting out, until you rose up the hierarchy. My mother remembered the Czech women, she said most were beautiful, intelligent, good cooks, elegant dressers. But back to my professor. You’ve heard of the linguist Roman Jakobson. Well, my professor was his wife. And Jakobson was our linguistics professor, a wonderful man, he loved . . .

Daciana Branea: . . . his wife.

Michael Heim: He loved her, but they had just divorced. I never saw them together. I was her student, and his. She taught Czech and was a wonderful woman. She was a true Central European—just like my mother had described—not only cultured and refined, but she had traveled widely, knew everyone. So that’s how I ended up studying Czech and learning what espresso was. With that language, it seemed a whole new world opened up in front of me. I decided to go to Prague. My professor was so interesting that I thought all Czechs would be like her. Of course, it wasn’t like that. But that was a good time to visit Czechoslovakia. I got there in ’65, when things were beginning to open up. The Soviet Union in 1962 and Czechoslovakia in 1965 were like night and day.

Daciana Branea: Is that when you met Havel?

Michael Heim: Yes, and this was how it happened. My aunt and uncle visited me that year, I was very close to them. This was the Uncle Leonard I confused for the head of the Citizens Exchange Corps. I told them I was studying Czech. As it turned out, everyone else I told this to thought it was a silly idea. Why would anyone want to learn Czech? No one had heard anything about Czechoslovakia since 1938 and Munich. But my aunt, instead of saying it was strange, said, “Oh, a good friend of mine from school is a journalist and lives there with her family.” So I had a place to stay in Czechoslovakia. That family’s children introduced me to their friends. There weren’t too many Americans around, and I was an American who spoke Czech, so people wanted to meet me. Two weeks after I got to Prague, I was taken to the premiere of one of Havel’s plays. And now I think it was one of his best works, Memorandum, a satire of bureaucratic language, but also an allegory of the entire Communist system. I hope it’s been translated into Romanian. Afterward, I was introduced to Havel as an American guest. But I have never met him again. I admire him immensely, I wrote a detailed study of Letters to Olga, I translated his address at UCLA a few years ago, and I teach his plays to my students (they work very well because they help young people understand how the regime functioned). But I can’t say we are friends.

Adriana Babeţi: How did you come to Serbo-Croatian?

Michael Heim: That happened much later.

Adriana Babeţi: So, in order, what language came after Czech? Hungarian? Why?

Michael Heim: Hungarian, but not for sentimental reasons. I said earlier that my grandparents were part of the respectable bourgeoisie—not upper, not lower—they had a few bakeries. They also had a house that my father had placed under my name. And because I was an American citizen, born in America, when they nationalized the houses, no one could touch it. And so, when I visited my grandmother in the same year, 1962, she told me about his house. She said, “You are Hungarian,” (she was a great patriot, that’s why she didn’t want to come to America), “and this is your house. You can come here whenever you want.” I went to a lawyer and asked him to send money to my grandmother. I sold the house. When she found out, she started to cry, so I went back to the lawyer. Because I was only 19, not 21, it turned out the sale had not been legal, so the house had never been sold. Later, many years after my grandmother died, I did sell it, and not understanding how business works, I lost all the money. So. Since I had to do business with Hungarians, I began to study Hungarian . . . At that time, I had already started to work as a translator. I had to stay in Hungary a few weeks to resolve some legal problems, and there I met a woman from the state literary agency—another Central European woman who matched my positive stereotype—and we talked about literature; this was my interest. She asked me who my favorite author was. I said, Chekhov. (He still is.) She gave immediately me a novel by Örkény, which I translated right way. Word for word, the title is Exhibition of Roses. I don’t know if it was translated in Romanian, but it is a superb book, really great. A TV reporter wants to film three people in the throes of death, to capture the moment when life passes into death. He finds three people about to die, and he follows them . . . step by step. The novel (actually, more of a novella, a hundred something pages) is a study of the ways art changes life. The moment something is made into art, it is no longer the same as it was before. It is an extraordinarily refined story. I tried to find someone to make a version for television. The text still feels current, not confined to the Communist period. There are some political references, but they aren’t the most important part. It’s about art—television as an art form—and art’s influence on life. I spoke once with the author, and he told me that the idea for the novella came to him in New York, while he was watching a show on a similar theme, and he re-set the story in Hungary.

Daciana Branea: How would you describe your knowledge of Hungarian?

Michael Heim: Every time I translate something from Hungarian, I have to re-learn the language. It’s hard, because Hungarian is very different from the other languages I know, and I began to learn it rather late. I was about forty.

Daciana Branea: So, you know the language more passively.

Michael Heim: Not passively, exactly. A translator must have a more than passive understanding of the language he translates. That’s why I am here. If I want to learn Romanian well enough to translate, I have to know how people talk and to be able to reproduce what I hear. I can do this in Hungarian. I could say in Hungarian everything I am saying now, without it seeming too forced, but it would take a little time to form the sentences, to get used to the language. I have to start from the beginning every time, and every time it gets easier. Still, it is the most difficult language I speak.

Adriana Babeţi: What came after Hungarian?

Michael Heim: Serbo-Croatian, and for a very simple reason: money.

Adriana Babeţi: Like Spanish?

Michael Heim: No, I didn’t make a penny from it. My university was low on money when the person who had been teaching Serbo-Croatian retired. If there had been money, the university would have hired someone else. But at about the same time, I met a Serbian film director, Vida Ognjenović—she taught with us for a semester—who commanded me, “You must learn our language.” I didn’t understand at the time why she had said, “our language.” It was, in fact, a way to avoid saying “Serbian” or “Croatian,” something people still do today. This was in 1984, and it was a problem even then. A deep-seated one, even if no one would have admitted it. Today, it is not possible to use the term “Serbo-Croatian.” We could talk about this, but it is a very delicate subject. At that time, you could still say some things, it wasn’t such a serious issue. So I decided to learn the language. Vida was a good friend of Danilo Kiš, who was looking just then for a translator for The Encyclopedia of the Dead. This was the first book I translated from Serbo-Croatian. I met the writer once in Belgrade and another time in Paris.

Adriana Babeţi: Was there anything after Serbo-Croatian? You’re scaring us already.

Michael Heim: I decided after Serbo-Croatian not to study any more languages. I promised my wife. Because studying a new language meant spending time away from home. And here I am in Timişoara! This is a little personal. I promised my wife I would put a stop to it. But in 1992, I was at a conference in Newark where I met three Romanians: Mircea Mihăieş, Ioana Ieronim, and Adriana Babeţi. I realized there was a gap in my knowledge. I knew nothing about Romania. You asked me about Polish. It would be very difficult for me to learn Polish and to use it, actively, because of Czech, because the two languages are very close. If I picked up a text in Polish—not literature, but an essay or newspaper article—I could understand it. Once when I had to do it, I could. I had to read a book quickly, and I managed. I can read Polish, but only quickly, not slowly. I can understand the topic when I hear it spoken. But with Romanian, even though it is a Romance language, things are not as simple. You can’t read Romanian by knowing French, the way a Czech would read Polish. Whatever they say, no French or Italian or Spanish speaker can read Romanian without some preparation.

Daciana Branea: But can’t they understand spoken Romanian? Can’t Italians, for example?

Michael Heim: Can they? Maybe because Italians want to feel at home in any company. Or it’s their innate optimism. I understand why they might be able to do it more easily than others. But not even Latinity can work miracles, or erase two millennia. So I realized there was an entire area I knew nothing about. Judging by the people I was talking to, it was a fascinating world. I knew nothing about Romanian literature, but with such people . . . Another motivation was that, at that time, a colleague and I had decided to form a working group for Central European literatures and to make a list, to get a clear idea of what was translated into English from this area, what was well translated, what was poorly done and needed to be re-done, what had been done well but was no longer available. In each case, I asked two people for their opinion: someone whose native language was English, and another whose native language was the one under discussion. I had no problems finding people for any of the languages except Romanian. There was no one born in the United States who studied Romanian and Romanian literature. The Romanian person involved was wonderful—Virgil Nemoianu—but he had to do the work of two people. It’s true that there are American specialists—Daniel Chirot, Keith Hitchins, Gail Kligman, Katherine Verdery—who knew Romanian very well, but they are all social scientists.

So I hadn’t found anyone to translate from Romanian literature. This was the second reason, as I later realized. The third was that we had an excellent lecturer, from Bucharest.

Adriana Babeţi: Georgiana Gălăţeanu.

Michael Heim: Yes, Georgiana Gălăţeanu-Fărnoagă. She was in our department, and I could ask her questions. This project took several years. In the meantime, I spent a month in Italy, where I had to give a paper in Italian.

Adriana Babeţi: In Bologna?

Michael Heim: Yes, Bologna, then Padua, in the north. I was glad to learn the language, since I wanted to read a wonderful book, Magic Prague by Ripellino. He created a new genre of literature, also used by Claudio Magris. The book is called Magic Prague and subtitled romanzo saggio, novel-essay. It was a fascinating book. It includes about 150 fragments of cultural and personal history. The book may also be read as an elegy for the past. It was written in ’71-’72, the darkest period of recent Czechoslovak history. I am proud that I ended up translating it.

Dorian Branea: It would be interesting to hear how you choose the novels you translate . . .

Michael Heim: I would like to choose the novels I translate. I make suggestions, of course, but, at least recently, publishers are very concerned with finances and target profitable books. Usually, I have very little say. So whenever I propose a book, I try to use a different approach, but my approach consists in telling publishers why the book is important to a particular tradition and why the English-language public will appreciate it. Quite often, publishers will send me a novel for an evaluation, which I am glad to write—sometimes positively, sometimes the opposite. I think this is a very important side of my work, the “secret” side. The responsibility is enormous. No one has ever published a book I rejected . . . but I cannot say that all the books I recommended were published. The problem is, whenever I recommend a book myself, people think I want to translate it too, even if this is the furthest thing from my mind.

Dorian Branea: What, then, attracts you most about a book?

Michael Heim: The first thing is the language. I don’t want to say that the ideas are completely unimportant. For me, at least, it’s not the ideas in the text that count, but its literariness. What is literature, in the end? I was trained as a structuralist and I think this has given me great freedom of movement.

Dorian Branea: Do you believe that the structuralists were able, as they dreamed, to create “a science of literature”?

Michael Heim: I don’t think that’s the question. I don’t think we need a science of literature. In any case, we don’t need the word “science.” If you want to say science, just do so. The fact that I claim that what I do is “scientific” doesn’t help me at all to read a book. Probably, for those who are in the social sciences it is important to believe they are a branch of science. I don’t care. One example: Bakhtin. His theory helped me to see things in some books—especially Švejk—that I would have missed otherwise. And yet, Bakhtin cannot be applied everywhere, he is not universal. But we don’t need universal answers in literary criticism.

Dorian Branea: Vasile Popovici, in his book The Character’s World, makes a persuasive critique of the dialogical; looking at a series of Romanian and foreign novels, he decides that this term is insufficient, too restrictive, and he offers instead the trialogical, a term drawn from ancient Greek tragedy, where the epic event is viewed from three perspectives at the same time.

Michael Heim: I met Vasile Popovici yesterday, but we didn’t have a chance to speak about this. I will have to ask when I see him next. In any case, it’s true that, in literary criticism, no theory excludes—or should exclude—any other. Marxist criticism, for example, in its ideological form, is awful. Like feminist or psychoanalytic criticism. At the same time, there are many valuable things in each, as long as they don’t claim to be exclusive.

Sorin Tomuţa: Part of your academic career has been dedicated to the study of translation. You are, likewise, a well-respected translator, working from languages that most Americans would consider exotic. Is a successful translation a personal version of the original?

Michael Heim: Anyone who has tried to translate a full literary work, not just a few pages, knows that translation is interpretation. You must interpret in order for the translation to come out well. I could give thousands of examples. Yes, certainly, translation is interpretation, and you can see this best if you compare two translations of the same text. You can tell right away that there are two minds at work on the same problem, each from a different point of view. Two people never translate the same sentence the same way. This claim leads to a part of your question: how can a future translator be taught? In the first place, the translator must be a careful reader of literature, which means he should study not only the history of the literature in which he wants to specialize, but also various techniques of researching or analyzing text, explications de textes.

In my literary translation seminar, I try to bring together students with different maternal languages. I don’t work separately with those who know French or Spanish or German. If you work like that, you tend to focus on what translators call the source language, the language from which you translate. The seminar becomes a language class, rather than one on translation. For me, the target language is much more important in training a translator, the language into which you translate. This is the language that will be read, what really counts. This doesn’t mean that the other language is not important. Of course it is. But only as “a technical detail.” You have to know the language from which you translate, you have to know it well enough to know how much of it you don’t know. In my seminar, students have to bring, every week, a fragment from a literary text they have translated, fragments that we discuss together. We discuss, more exactly, the literary nuances of different English choices. It is amazing that, even though not all the students know the original language, they can find the mistakes exactly, just because the English text is unclear or makes no sense. The one doing the translating can’t see it, because he is too immersed in the source language. So it’s not a problem to work with people who don’t necessarily know the original language. Often I don’t know it, myself. This past spring, for example, students were working from Arabic and Armenian, languages foreign to me, and yet my comments and those from the other students were just as relevant as what we said about texts from French or Spanish. And this method can be used anywhere. In our university, each trimester is ten weeks long, and of course you can’t make someone a translator so quickly, but what you can do is to show someone the work is worth doing more of, in the future. I often see students surprised to discover that they can be translators, even publish. All of the seminars up to now have produced translators who publish translations of major works. I think it is important that all over the world there be a sustained interest in translation, since with this kind of training you create a team of active people, that is, people who will not wait for the publisher to sign a title that has to appear. If every university with a strong Comparative Literature department began to produce qualified translators, they could start to work immediately, and then there would be more opportunities for foreign authors to reach their audience. This is true everywhere, not just in our country.

•

Adriana Babeţi: Dear Mike, I don’t even dare ask you my next question. If you tell me there are people in your country who haven’t heard of Dante or Balzac, what can we say about Hašek or Kundera, Kiš or Esterházy? What is happening with Central European literature in the United States? How is it regarded?

Michael Heim: I have said that in this immense mass of people are smaller groups, of tens, hundreds, or even thousands of readers. All it takes is for the works to be translated. Even if they are not read by hundreds of thousands of people immediately—so I tell myself when I translate, to quiet my fears—they will be in the libraries. I once met someone who, on hearing I was a Slavics professor, told me he had just taken a great novel out of the library, by the Serb, Crnjanski: Migrations. He wanted to know if I had read it, and if I hadn’t that I should. You can’t imagine how happy it made me. Or I might see someone on an airplane reading a book I have translated. I’m moved. It’s not every day, but still, it’s happened a few times. Even if the novels sell poorly (an average print run is no more than two thousand, in a country as large as the U.S.), I don’t think this matters. There will always be that loyal “gang,” people who aren’t even aware how exceptional they are. I do what I do for these people. I know that it is important for them to read Hrabal, Esterházy, Ugrešić, Kiš, or Crnjanski.

Adriana Babeţi: How many books from this part of Europe have you translated?

Michael Heim: I couldn’t tell you unless I went home and counted. I haven’t kept track. Over twenty, I think. But I’ve also translated from Russian. A different cultural area.

Adriana Babeţi: Of all Central European authors translated, who are the best known in the United States?

Michael Heim: Kundera, Kundera, Kundera. By far. All intellectuals have heard of him. Whether they’ve read him is a different story. But they enjoy playing with the title of his best-known novel The Unbearable Lightness of Being, going on about the unbearable lightness of this and the unbearable lightness of that. I laugh when I run across newspaper headlines adopting the formulation. The editor who commissioned me to do the translation first heard the title over a bad transatlantic phone connection from Kundera in French. All he could make out was that it consisted of three abstract words. I realized a title consisting of “three abstract words” would be a hard sell in the US but was surprised the initial opposition to a literal translation came from Kundera himself. “I realize that for you Americans the title will be a bit hard-going,” he told the editor, “so we can try something else.” And he suggested one of the chapter titles: “Karenin’s Smile.” I protested. “We’re not children,” I told the editor. “If The Unbearable Lightness of Being is the title, so be it.” And so it stayed. I’m glad I pushed for it. Even the film based on the book adopted it. Unfortunately, the film, though a box-office success, failed to take advantage of the cinematic structure inherent in the novel.

Cornel Ungureanu: How would you describe Kundera’s relationship with the Czech spirit?

Michael Heim: Kundera now calls himself a “European writer.” And that’s what he is. He wrote his last two books directly in French. But for me, he is still a Czech writer. And he is extremely conscious of his roots. He wrote a study of Vladislav Vančura, a great Czech novelist, unknown abroad, because he is very hard to translate. His material is very Czech. Maybe one day I’ll attempt a translation.

Cornel Ungureanu: Czech writers have a strong relationship with Czech directors . . .

Michael Heim: Yes, Kundera himself didn’t teach at a school of letters, but at the well-known Prague film school. He taught French literature there. Film is extremely important in this relationship. It has helped me personally to promote Czech literature in the American market. Czech culture had already impacted the public through Menzel or Forman. I remember the Oscar for Menzel’s film Closely Watched Trains. Because of it, I was able to win the battle for the novel on which it’s based. Also important were the events of 1968.

Cornel Ungureanu: Is that when you met Hrabal?

Michael Heim: No. I met him in 1965 when I was in Czechoslovakia and he was introduced to me as the most important living Czech author. I’d like to go back for a moment to Kundera’s Czech roots. In that study of Vančura, Kundera also admits he owes a great deal to Čapek. Whoever has read The Joke can see it. Čapek argues in most of his novels, including An Ordinary Life, that there are no mediocre, banal, indistinguishable lives, that each one has its own purposeful biography, and thus its own point of view, its personal vision.

Cornel Ungureanu: How did Hrabal strike you then, in 1965?

Michael Heim: He was my true introduction to Central European literature. Through him, I discovered a completely new universe. In my opinion, Hrabal is the incarnation of Central Europe. Because his works have all the major themes of this area, but not in an elevated, highbrow way—quite the opposite. Everything Hrabal does is extremely popular, but it is clear also that he is a very cultivated person. He knows German literature and philosophy very well, especially Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, and even Hegel.

Daciana Branea: Which Central European literature is the best known in the U.S.?

Michael Heim: Certainly Czech literature, because of Kundera.

Daciana Branea: Was his article, “The Tragedy of Central Europe,” as important as they say?

Michael Heim: It was extremely important, only because it came after Kundera was already celebrated as an author. Kundera became known in the States as a writer first, for The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, at the beginning of the ’80s.

“The Tragedy of Central Europe” was an important explanation of “the other Europe.” Earlier, Philip Roth had started a series of translations from Central European literatures, called “Writers from the Other Europe.” This became the place to go to find all these authors. You, an ordinary American reader, not knowing which books to choose, you could let Roth judge for you. He could be your guide . . . and so he was for many people. And his name was on the cover of every book, printed just as large as the name of the author. I’m sure the publishers did this on purpose, because they knew it was much more likely that the American reader would buy a book with Philip Roth’s name on the cover than one with a name no one could pronounce and no one had seen before.

Daciana Branea: You were saying that Czechoslovakia enticed you because you had heard so much about its beautiful women. Were you disappointed?

Michael Heim: I came to Czechoslovakia for the first time in the summer of 1965. I was 22, and the quality to which you refer was very important . . . and I was completely satisfied [laughter] . . . by what I found. I don’t mean only the women, but everyone my age. I learned something that surprised me about myself: they taught me how “American” I was.

I had been in the Soviet Union three years before. This was 1962, my first trip to Europe, and I was very naïve, in the best sense of the word. I didn’t have any preconceived ideas. I was simply horrified by all I found there: the lack of freedom, the fear . . . When I came to Czechoslovakia, everything was different. I met people my own age who knew how to stand up to the system, how to manage within it, and who were not at all afraid. They weren’t afraid, for example, to have a conversation with a foreigner. While in the Soviet Union, you planned your meetings far in advance, and if you met someone in the street, for example, you could only say a few words because you knew you could make trouble for them. In Prague there were no such problems.

Daciana Branea: What were the major differences between Czechoslovakia and the USSR?

Michael Heim: The most important was the fact that there, in 1965, people trusted each other. And they could say whatever they wanted. Even if they didn’t do it in public, they were as free as possible with each other. For me, the most important thing was that I learned you shouldn’t believe everything you read, and my friends were much more sophisticated readers than I was. Readers of magazines, but by extension, readers of everything, including literature. I had been schooled to believe that everything I read was, more or less, true. And more or less, everything I had been reading was true. My Czech friends were used to questioning everything, while I tended to accept it.

Daciana Branea: What did they read?

Michael Heim: They read everything they could. They also translated, here and there. But Czech literature was becoming more and more interesting. I constantly asked them who were the best writers of the moment, because there were some exceptional young writers. The first time I was in Czechoslovakia, I had only studied the language a year, so of course I wasn’t ready to read literature. But I went back the next year, in 1966, and again in 1968, and I learned a lot about a group of authors that now everyone knows about, today they are a part of world literature. The most important names were Hrabal, Kundera, Škvorecký. At the time, completely unknown outside of Czechoslovakia. My first summer there, 1965, I met Havel. As I have mentioned, we didn’t become friends, but I shook his hand at the premiere of Memorandum.

Daciana Branea: Who was the first Czech author you translated, and why?

Michael Heim: The first author I tried to translate into English was Škvorecký, whom I had met. Škvorecký knew English, it was his professional specialty. I decided to translate one of his stories, and when I got back to New York, I sent it to a publisher. It was one of his detective stories. This translation was an important lesson for me. The publisher said that he had read the story and he liked it, but . . . the translation had some slips. He showed me one mistake: I had translated a word meaning “tanned” as “sun-burnt.” A huge mistake, one stemming not from a lack of knowledge of Czech, but negligence of my English. I realized I could never let that happen again, that I needed to pay close attention to my own language. I learned that a translator is a writer in his native tongue, and the language from which he translates is nothing but—as I like to say, in exaggeration—a “technical detail.” Of course, you must know the language you translate from, but if you don’t understand the text well enough, the game is not lost, because you can ask a native speaker for help. The most important thing is to master the language you translate into.

Daciana Branea: When you began your career as a translator of Central European literature, was there already significant interest in the United States?

Michael Heim: Not a trace.

Daciana Branea: So you were a kind of pioneer.

Michael Heim: I was a lost pioneer. First, because my first translation was not good—the publisher was right—then because I was very young and no one took me seriously. Between 1966 and 1968 I practiced with prose fragments, trying to catch the attention of American publishers. I was sure that these authors were very good. But again, I couldn’t find anyone to listen to me. Then came 1968.

Daciana Branea: How were you received, as an American, at that time? It was the Czech “Jazz Age” . . .

Michael Heim: Yes, the Czechs at the time were fascinated by American music and literature. The same could not be said of the USSR, where the propaganda was so powerful that people either believed it absolutely or thought it was completely false and, as a result, thought the U.S. was a kind of inaccessible paradise. The Czechs were much, much more sophisticated. Most of their parents were middle class, bourgeois, from the time when “bourgeois” was a neutral term. Many had suffered during early Communism. Yet, one way or another, they managed. I was born in 1943. If my friends were born, let’s say, in 1943, it means they started school in 1948, the first year of the Communist regime.

Daciana Branea: So they grew up with it.